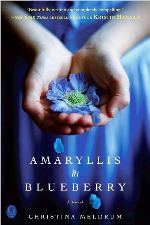

With Amaryllis in Blueberry, Christina Meldrum delivers a story that is part coming-of-age and part culture clash. The story follows the Slepy family as they leave the comfy confines of Michigan for missionary work in West Africa. Your group can win an author chat with Christina and copies of Amaryllis in Blueberry (in stores February 8th) by registering here. In this interview, Christina talks about her own work in West Africa and the influence of her legal career upon one of the book's key scenes.

Q: Amaryllis in Blueberry takes place in Michigan and West Africa. What personal significance do these landscapes have for you? What appealed to you about using two such dramatically different locations in the novel?

A: I grew up in Michigan and continue to spend time there every summer. Although I no longer live in Michigan year-round, it will always be home to me at some level. Michigan represents family to me. It represents summers on the lake. It represents holidays. While the characters in Amaryllis in Blueberry are purely fictional, the Danish Landing is very real. My family has owned property on the Danish Landing for over a hundred years. Nearly all of my most poignant childhood memories take place on the Danish Landing. I remember my grandmother standing at the stove flipping blueberry pancakes. I remember exploring the Old Trail. The Danish Landing gave me my first campfire, my first sunburn, my first leech! To the degree any place on earth makes me feel grounded, the Danish Landing does. I imagine Yllis would find part of my soul on the Danish Landing.

A: I grew up in Michigan and continue to spend time there every summer. Although I no longer live in Michigan year-round, it will always be home to me at some level. Michigan represents family to me. It represents summers on the lake. It represents holidays. While the characters in Amaryllis in Blueberry are purely fictional, the Danish Landing is very real. My family has owned property on the Danish Landing for over a hundred years. Nearly all of my most poignant childhood memories take place on the Danish Landing. I remember my grandmother standing at the stove flipping blueberry pancakes. I remember exploring the Old Trail. The Danish Landing gave me my first campfire, my first sunburn, my first leech! To the degree any place on earth makes me feel grounded, the Danish Landing does. I imagine Yllis would find part of my soul on the Danish Landing.And I imagine she'd find another part of my soul in West Africa. I worked for a short time in West Africa during my 20s, and I continue to have ties to West Africa through my nonprofit work. To the degree the Danish Landing is my place of peace, West Africa is my place of prodding. West Africa nudges me, with its energy and rituals, its colors and smells. As a twentysomething living in West Africa, I did not feel peaceful, but I sure felt alive. I did not feel grounded; I felt flung from Addae's slingshot. And when I landed, I had a different perspective, one that was far more nuanced. I was drawn to writing about these two places because on the surface they are so very different, but beneath the surface of each, there's another world. And these beneath-the-surface worlds are surprising --- and surprisingly similar in many ways.

Q: The slave castles visited by the Slepy family on their journey in West Africa are a haunting aspect of the novel. Why did you choose to include them as a setting in the story?

A: There is a line in Amaryllis in Blueberry in which a character [Ylis] refers to "the painful, beautiful truths that hover about like gnats…so often we just swat them away." To me, slavery is one of those painful truths we often swat away. It is part of West Africa's past. It is part of our past. But slavery is not the past. Like Yllis would say: the slave souls live on; slavery lives on. Be they trokosi or victims of the sex trade or the drug trade or the disfigured girl on the cover of Time magazine who tried to escape her Taliban "owner," girls and boys and women all over the world are enslaved every day. The slave castles are a reminder of that. They're the gnats. They're the decapitated rattler. Like Yllis would say: "[T]here is a painful sort of beauty in seeing things for what they really are." In that regard, the slave castles are symbolic of a related issue: how was each character in Amaryllis in Blueberry enslaved at some level: by others' perceptions, expectations and memories of him/her; by the character's memories and self-perception; by others' choices; or by the confines of his/her culture? How and to what degree is each of us similarly enslaved?

Q: What was the most challenging aspect of writing Amaryllis in Blueberry? How was the experience different from that of your young adult novel, Madapple?

With both Madapple and Amaryllis in Blueberry, ideas spurred my writing at the outset, more than plot or character did. When I began Amaryllis in Blueberry, I was interested in exploring the way myth and perspective help shape humans' sense of reality and identity. I wanted to embed my own story in a myth --- the myth of Pandora --- and allow that myth to help shape the reality and identities I created. At the same time, I wanted to tell my own story from many perspectives: past and present, first person and third person, eight characters, starting with the end, ending with a voice that until that point had had no voice. I was trying to do a lot with ideas and structure, and at first my characters seemed lost in those ideas and structure. It took my having a terrific editor and agent and some wonderful reader friends who directed me back to my characters. With their help, I really came to know my characters, but it was tough, because there were a lot of them. Unlike with Madapple, which I told mainly in first person from the perspective of one character, in Amaryllis in Blueberry I had to know all eight characters intimately. In order to do this, I realized I needed to write them all in first person, then shift their voices (all but Yllis) back to third person. This was time-consuming and challenging, but it helped tremendously.

Q: Amaryllis in Blueberry and Madapple both have a character that is put on trial. Did your background as an attorney come into play in deciding to include these scenes? How is Seena's trial most different from one that would take place in the U.S.?

A: I am interested in justice: What is it? How do we decide? Is justice independent of culture? Or is there some fundamental form of justice that exists irrespective of culture? The trials in both of my books were means by which I hoped to explore these questions. Seena's trial in Africa was dramatically different from the trial in Madapple, where Aslaug was said to be "innocent until proven guilty." And yet, was it really that different? Of course, in some fundamental respects the trials were night and day. As Seena said, Okomfo and Queen Mother were her "accusers, judge and jury." But as the trial in Madapple suggests, our system of litigation, with its lawyers, judges and juries, does not necessarily arrive at truth in the end --- any more than did Okomfo and Queen Mother. Cultural assumptions and prejudices played a role in both trials. Hence, the question: particularly with regard to the rights of any subset of society, be it women or the disabled or a particular ethnic group, should cultural norms be relevant to determinations of what is just and unjust? The more time I spent thinking about these issues, the less obvious the answers became to me. Hence, I stopped practicing law. And started writing.