Excerpt

Excerpt

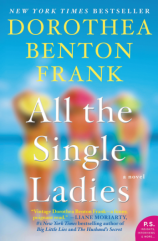

All the Single Ladies

CHAPTER 1

Meet Lisa St. Clair

June 2014

I hail from a very theatrical climate. Coming to terms with Mother Nature is essential when you call the Lowcountry of South Carolina home. At the precise moment I ventured outside early this morning, my sunglasses fogged. In the next breath I swatted a mosquito on the back of my neck. The world was still. The birds were quiet. It was already too hot to chirp. And, Lord save us, the heat was just beginning to rise. I thought the blazes of hell itself could not be this inhospitable.

But that was exactly how a typical summer day would be expected to unfold. The temperature would climb steadily from the midseventies at sunrise to the edges of ninety degrees by noon. All through the day thermometers across the land would inch toward their worst. Around three or four in the afternoon the skies would grow black and horrible. After several terrifying booms and earsplitting cracks of thunder and lightning, lights would flicker, computers reboot, and the heavy clouds burst as rain fell jungle style—fast and furious. Natives and tourists declared it “bourbon weather” and tucked themselves into the closest bar to knock back a jigger or two. Then suddenly, without warning, the deluge stops. The sun slowly reemerges and all is right with the world. The good news? The stupefying heat of the day is broken and the sun begins its lazy descent. The entire population of the Lowcountry, man and beast, breathes a collective sigh of relief. Even though every sign had pointed to impending catastrophe, the world, in fact, did not come to an end.

After five o’clock, in downtown Charleston, gentlemen in seersucker, linen, or madras, wafting a faint trail of Royall Bay Rhum, would announce to freshly powdered ladies in optimistic chintz that it appeared the sun had once again traveled over the yardarm. Could he tempt her with an iced adult libation? She would smile and say, That would be lovely. Shall we imbibe on the piazza? I have some delicious cheese straws! Or deviled eggs, or pickled shrimp, or a creamy spread enhanced with minced herbs from their garden. Ceiling fans would stir and move the warm evening air while they recounted their leisurely days in sweet words designed to charm.

By six or seven in the evening, across the city in all the slick new restaurants with dozens of craft beers and encyclopedic wine lists, corks were being pulled. Freezing-cold vodka and gin were slapping against designer ice cubes in shiny clacking shakers, with concoctions designed by a mixologist whose star was ascending on a trajectory matched with his ambition. Hip young patrons in fedoras and tight pants or impossibly high heels and short skirts picked at small plates of house-cured salumi and caponata. At less glamorous watering holes, crab dip was sitting on an undistinguished cracker, boiled peanuts dripping with saline goodness were being cracked open, and pop tops were popping.

An afternoon cocktail was a sacred tradition in the Holy City and had been as far back as the War. Charlestonians (natives and the imported) did not fool around with traditions, no, ma’am, even if your interpretation of tradition meant you’d prefer iced tea to bourbon. When the proper time arrived, the genteel privileged, the hipsters, and the regular folks paused for refreshment. If you were from elsewhere, you observed. We were so much more than a sea-drinking city.

But I was hours away from any kind of indulgence and it was doubtful I’d run into someone with whom I could share a cool one in the first place. To be honest, I was a juicer and got my thrills from liquefied carrots and spinach, stocking up when they were on special at the Bi-Lo. And I was the classic case of “table for one, please.” Such is the plight of the middle-aged divorcée. I had surrendered my social life ages ago. On the brighter side, I enjoyed a lot of freedom. There was just me and Pickle, my adorable Westie. We would probably stroll the neighborhood later, as we usually did in the cool of early evening.

This morning, I finally got in my car and braved the evil heat baked into my steering wheel. I turned on the motor and held my breath in spurts until the air-conditioning began blowing cool air. My Toyota was an old dame with eighty-five thousand miles on her. I prayed for her good health every night. As I turned all the vents toward me I thought, Good grief, it’s only June. It’s only seven thirty in the morning. By August we could all be dead. Probably not. It’s been like this every sweltering summer for the entire fifty-two years of my life. Never mind the monstrous hurricanes in our neck of the woods. I’ve seen some whoppers.

As I backed out of my driveway an old southernism ran across my mind. Horses sweat, men perspire, but ladies glow. Either I was a horse or I was aglow on behalf of twenty women. I’m sorry if it sounds like I’m complaining, which I might be to some degree, but during summer my skin always tastes like salt. Not that I went around licking myself like a cat. Even our most sophisticated visitors would agree that while Charleston could be as sultry and sexy a place as there is on this earth, our summers are something formidable, to be endured with forethought and respect. Hydrate. Sunscreen. Cover your hair so it doesn’t oxidize. Orange hair is unbecoming to a rosy complexion.

It was an ordinary Monday and I was on my way to work. Oppressive weather and singledom aside, my professional life was what saved me. I’ve been a part-time nurse at the Palmetto House Assisted Living Facility for almost five years. The only problem, if there was one, was that I barely earned enough money to fulfill my financial obligations. But a lot of people were in the same boat or worse these days, so I counted my blessings for my good health and other things and tried not to think about money too much. I grew tomatoes and basil in pots on my patio, and I took private nursing jobs whenever they were available. I was squeaking along. And when I got too old to squeak along I thought I might commit a crime, something where no one got hurt, so that I could spend the rest of my days in the clink. I’d get three meals a day and health care, right? Or maybe I’d marry again. Honestly? Both of these ideas were remote possibilities.

My nursing specialty was geriatrics, which I’d gravitated toward because I enjoyed older people. Senior citizens are virtual treasure troves of lessons about life and the world. They hold a wealth of knowledge on a variety of subjects, many of which would have never been introduced to me if not for the residents of Palmetto House. The truth be told, those people might be the last generation of true ladies and gentlemen I’d ever know. They are conversationalists in the very best sense of the term. The time when polite conversation about your area of expertise was a pleasure to hear, I am afraid, is gone. These days young people speak in sound bites laced with so many references to pop culture that confuse me. The English language is being undermined by texting and the Internet. LOL. ROTFLMAO. BRB. Excuse me, but WTF? TY.

There was a darling older man, Mr. Gleason, long gone to his great reward, who would exhaust himself trying to explain the glories of string theory and the nature of all matter to me. To be honest, his explanations were so far over my head he could have repeated the same information to me like a parrot on methamphetamine and it never would have sunk into my thick head. But it made him so happy to talk about the universe and its workings that I’d gladly listen to him anytime he wanted to talk.

“You’re getting it, you’re getting it!” he’d say, and I would nod.

No, I wasn’t.

I had a better chance with Russian history, wine, Egyptian art, astronomy, sailboat racing, the Renaissance, engineering—well, maybe not engineering, but there were Eastern religions—and a long list of different career experiences among the residents. Whenever I had a few extra minutes, it was a genuine pleasure to sit with them and listen to their histories. I learned so much. And just when things were running smooth as silk, believe it or not, there was always one man who’d have someone from beyond our gates slip him a Viagra or something else that produced the same effect. This old coot would go bed hopping until he got caught in the act or until the ladies had catfights over the sincerity and depth of his affection. Then Dr. Black, who ran Palmetto House, would have to give Casanova a chat on decorum even though his own understanding of the term might have been somewhat dubious. What did he care? The evenings would be calm for a while until it happened again. The staff would get wind of it and be incredulous (read: hysterical) at the thought of what the residents were doing. I’d get together with the other nurses and we’d all shake our heads.

“You have to admire their zest for living,” I’d say.

Then someone else would always drop the ubiquitous southern well-worn bomb: “Bless their hearts.”

Like many senior facilities we had a variety of levels of care from wellness to hospice and a special care unit for patients with advanced dementia. About half of our residents enjoyed independent living in small, freestanding homes designed for two families. They frequented the dining room and swimming pool and attended special events such as book clubs, billiards tournaments, and movie nights. They used golf carts to visit each other and get around. As their mobility and their faculties began to take the inevitable slide, they moved into the apartments with aides and then single rooms with nursing care where we could check on them, bring them meals, bathe and dress them, and of course, be sure their medications were taken as prescribed. For all sorts of reasons, our most senior seniors were often lonely and sometimes easily confused. But the old guys and dolls always perked up when they had a little company. It was gratifying to be a part of that. Improving morale was just a good thing. The other perk was that the commute from my house to Palmetto House was a breezy fifteen minutes.

This morning I pulled into the employee parking lot and kept the engine running while I prepared to make a mad dash to the main building. I spread the folding sunshade across my dashboard to deflect the heat and gathered up my purse, sunglasses, and umbrella. My shift was from eight until four that afternoon. The inside of my car would be steaming by then, even if I lowered my windows a bit, which I did. Otherwise how would the mosquitoes get in? If I didn’t lower the window a bit I always worried that my windshield might explode, and who’s going to pay for that?

I hopped out, my sunglasses fogged over again, I clicked the key to lock the doors, and I turned to hurry inside as fast as I could. I could feel the asphalt sinking under my feet and was grateful I wasn’t wearing heels, though, to be honest, I hadn’t worn heels since my parents’ last birthday party.

The glass doors of the main building parted like the Red Sea and I rushed toward the cooler air. Relief! By the time I reached the nurses’ station I was feeling better.

“It’s gonna be a scorcher,” Margaret Seabrook said.

Margaret and Judy Koelpin, a transplant from the northern climes, were my two favorite nurses at the facility. Margaret’s laser blue eyes were like the water around the Cayman Islands. And Judy’s smile was all wit and sass.

“It already is,” I said. “The asphalt is a memory-foam mattress.”

“Gross,” Judy said. “I wanted to go to Maine on vacation this August, but do you think my husband would get off the boat to go somewhere besides the Gulf Stream?”

Judy’s husband loved to fish and won one competition after another all year round.

Margaret said, “That’s a long way to go for a blueberry pie.”

“I love blueberry pie,” I said.

“Before I die, I want to spend an August in Maine,” Judy said. “Is that too much to ask?”

“I think the entire population of Charleston should go to Maine for the month of August,” I said.

“Too far,” Margaret said. “Besides, we’d miss the second growth of God’s personal crop of tomatoes here! True happiness comes from what grows in the Johns Island dirt.”

“Tomatoes and blueberries are not the same thing,” Judy said. “And tomatoes are all but finished by August.”

“I can make them grow,” Margaret said.

“Yeah, and watch them explode in the heat,” Judy said.

I laughed at them. They were always bickering about food, mostly to entertain themselves. Not because they really disagreed on anything.

“You’re right,” Margaret said. “But tomatoes are way more versatile than blueberries. By the way . . . Lisa?”

“Yeah?” I threw my things in my locker and picked up the clipboard from the desk that had notes on all the patients. “How was last night?”

“Not great. Dr. Black wants to see you.”

“Oh no. Don’t tell me. Kathy Harper?”

“Yeah, she had a terrible night. We had to start her on morphine.”

Margaret’s eyes, then Judy’s, met mine. We all knew; morphine marked the beginning of the end. Kathy Harper was one of our favorite patients, but she was in a hospice bed fighting a hopeless battle against fully metastasized cancer. And she was the sweetest, most dignified woman I’d ever known. Her friends visited her every day and they always brought her something to lift her spirits. Brownies, tacos, granola, ice cream, a manicure, or a pedicure. The latest gift had been a documentary on the northern lights, something she had always wanted to witness. Sadly, a National Geographic DVD was as close as she would ever get.

“Are Suzanne and Carrie in there?”

“Yeah,” Judy said. “God bless ’em. They brought us a box of Krispy Kremes. We saved you a Boston cream.”

“Which I need like another hole in my head.” I picked the donut up and ate half of it in one bite. “Good grief. There ought to be a law against these things.” I ate the other half and licked my fingers.

“So, don’t forget, Darth Vader wants to have a word,” Margaret said.

“Can’t be good news,” I said.

“When is it ever?” she said.

His actual name was Harry Black but we called him Darth Vader and a string of other less than flattering names behind his back because he seldom brought tidings of joy. Harry was a decent enough guy. It seemed like he was always there at work. It couldn’t be easy for him to watch patient after patient go the way of all flesh and to be responsible for all the administrative details that came with each arrival and departure. If there was one thing in this world that I truly did not want, it was his job. But we enjoyed some sassy repartee, making it easier to contend with the difficult moments.

I took a mug of coffee down the hall and rapped my knuckles on his door.

“Enter!” he said dramatically, as though I’d been given permission to come into his private and mysterious inner sanctum.

I smirked, even though I knew I was about to hear heartbreaking news, and pushed the door open.

“G’morning, Dr. Black,” I said, walking in, and waited for him to tell me to sit. For the record, there was a half-eaten jelly donut on his desk between stacks of manila folders. Few humans I knew could resist the siren’s call of a Krispy Kreme donut.

“Sit,” he said. “Kathy Harper is failing. Pretty quickly. We have the unfortunate duty today of informing her friends that it’s time to cancel the pedicures.”

“Dr. Black? Did anyone ever accuse you of being overly sensitive?”

“Please. I know. But listen, you and I have been down this road a thousand times. She had a horrendous night last night. I had to sedate the hell out of her. She’s sundowning for the foreseeable future.”

“I am so sorry. I got the word from Margaret and Judy. The poor thing.”

“Yes. God, I hate cancer.”

“I do too. I don’t understand why some people who are nothing but a pain in the neck live to a hundred and die in their sleep, never having needed anything more than an aspirin. And other people like Kathy Harper have to suffer and die so young.”

“I know. It’s terrible. Anyway, our job here is to make the end bearable not only for the patient but for the family and friends.”

“Really? Dr. Black, I didn’t know that. I just got out of nursing school yesterday. Do you want me to tell them?”

“Yes, but do you have to be so sarcastic?” he said.

“Do you have to be so condescending?” I said, and stood up. “Jeez. They’re here, so I’ll go talk to them now.”

I stopped at the door, turned back, and rolled my eyes at him.

“Okay, okay. I know. I’m a jerk,” he said. “But you know what?”

“What?”

“I’m gonna miss all those donuts,” he said, and added in a mumble, “And the delicious legs on that little brunette.”

“You’re terrible,” I said, and left thinking maybe gallows humor rescued us on some days. In any case, it clearly rescued Dr. Black. Not getting emotionally involved was obviously easier for him than for me.

I walked down the hall and turned to the right, making my way to Kathy Harper’s room. It wasn’t the first trip I’d made from Dr. Black’s office with a message of this weight to deliver. Technically, it was his job to convey bad news but he hated doing it. And he knew I was very close with Kathy’s friends, and truly, I wasn’t going to tell them something they didn’t already know. But I was going to tell them something they didn’t want to hear. My heart was heavy.

I took a deep breath and slowly swung the door open. There was Kathy, peacefully sleeping in her bed, or so it seemed, with Suzanne seated on one side and Carrie on the other. Suzanne was checking her email on her smartphone and Carrie was flipping through a magazine. They looked up at me and smiled.

“Hey,” I said quietly. “How are y’all doing?”

“Hey, how are you, Lisa?” Suzanne said in a voice just above a whisper. “How was your weekend?”

What Suzanne and Carrie did not yet know was that Kathy was not really asleep but drugged and floating somewhere in what I hoped was a pain-free zone in between sleep and consciousness. I knew she could hear our every word.

“Well, I took Pickle over to Sullivans Island and we had a long walk. Then I drove down to Hilton Head to check on my parents. My dad cooked fish on the grill. We had a nice visit. How about y’all?”

“I had three weddings and a graduation party!” Suzanne said. “Crazy!”

“I helped,” Carrie said. “You know that Suzanne was desperate if she let me in the workshop.”

“Oh, hush! I would never have been able to get it all done without you and you know it!”

Suzanne owned a very popular boutique-sized floral design business. June was her busiest time of the year, followed by December, when she decorated the mantelpieces, swagged doors and staircases, and hung the wreaths of Charleston’s wealthiest citizens. Suzanne was a rare talent.

“Well, I was hoping to have a word with y’all. Should we step outside for a moment?”

“Sure,” Suzanne said.

They stood and followed me to a small unassigned office that served as a private place for conversations not meant to be heard by the patients. It held only an unremarkable desk, three folding chairs, and a box of tissues.

Before I could sit Carrie spoke.

“This is really bad news, isn’t it?” she said.

Carrie Collins had recently buried her husband in Asheville, North Carolina, and was enjoying an extended visit with Suzanne while her late husband’s greedy, hateful children contested his will. And she had become great friends with Kathy while working at Suzanne’s design studio. She’d told me that she arrived on Suzanne’s doorstep with only what she could fit in her trunk.

“Well, it’s not great,” I said. “Kathy had a really difficult night last night. So the doctor ordered morphine for her and that’s why she’s resting now. He thinks it’s time to begin administering pain meds on a regular basis.”

“Is she already going into organ failure?” Carrie said.

Boy, I thought, for a nonprofessional she sure is familiar with how we die.

“Oh God!” Suzanne exclaimed. “She can’t go yet! I promised her I’d take her out to the beach!”

“The minute I came in this morning I could smell death in every corner of her room,” Carrie said.

“Don’t be such a pessimist. She’s just having a setback, isn’t she?” Suzanne asked. “Do you think we can get her out to Isle of Palms? Maybe by next week?”

“To be honest?” I said. “Who knows? She has a living will that dictates the care she wants for herself, but when she’s unable to make decisions, like now . . . You have her health care proxy. Her will says she does not want to be resuscitated or intubated.”

“Yes. I know that,” Suzanne said.

“Anyway, we feel the time has come to provide maximum comfort for her. Her living will also says, as I’m sure you know, that she asked for pain medication as needed.”

“Are you asking my permission?” Suzanne said.

“Yes,” I said.

“Is she in pain now?” Carrie said.

“She was last night, but as you can see, she’s resting comfortably now,” I said.

“Then give her whatever she needs,” Suzanne said. “Please. God, I don’t want her to suffer!”

“She won’t suffer, will she?” Carrie said.

“We will do everything in our power to see that she doesn’t. I promise,” I said.

“Is this the end?”

This was the question every single person who worked at Palmetto House dreaded. I gave her the best answer I could.

“Oh, Suzanne. If I knew the answer to that, I’d be, well . . . I don’t know what I’d be. Einstein? The truth is that no one can precisely predict the hour of someone’s death. But there are signs. As she gets closer to the end, things will change, and I promise I will tell you all I know.”

Suzanne’s bottom lip quivered and she burst into tears, burying her face in her hands. Carrie’s eyes were brimming with tears too. She put her arm around Suzanne’s shoulder and gave her a good squeeze. They were both devastated. I pulled tissues from the box on the desk and offered them. Even though I’d seen this wrenching scenario play through more times than I wanted to remember, this seemed different. It felt personal. And suddenly I was profoundly saddened. I had become involved. In my mind, seeing Kathy Harper’s demise was like witnessing a terrible crash in slow motion.

“I’m okay. Sorry,” Suzanne said. “It’s just that this whole thing is so unfair.”

“Yes. It is terribly unfair,” I said, “But I can tell you this. Everyone around here has seen y’all come and go a million times since Kathy came to us. And every time you visit, her spirits perk up, and by the time you leave, she honestly feels better. Who could ask for better friends? Y’all have done everything that anyone could do.”

“Thank you,” Suzanne said, and then paused, gathering her thoughts. “Oh God! I really hoped, or I had hoped, that she’d get to a place where she could come to the beach to convalesce. The salt air would do her so much good.”

“Well, for now I think we just take one day at a time.”

“Yes,” Carrie said. “God, this stinks. This whole business stinks.”

“It sure does. But, listen. Keep talking to her, even when she appears to be sleeping,” I said, “because she can probably hear you. She just can’t respond. Y’all are helping her in ways you can’t even imagine.”

“And shouldn’t we pray?” Carrie said. “Prayer can’t hurt.”

“That’s right,” Suzanne said to no one in particular.

“Prayer helps everyone. I’ve seen some pretty amazing things happen when people pray.”

They looked at me and I knew they were hoping against reason that I was going to tell them I’d seen people miraculously cured. I’d heard of miracles, lots of them in fact, but I had not seen one. I was sorry. I wished I had. I wanted to give them hope where there was so very little, but I failed. I could not lie to them or give them false reassurance.

As the day crawled by, I became more and more disheartened. Every time I went by Kathy Harper’s room, she seemed a little worse. By the time I got home, I was beside myself with dread and all sorts of claustrophobic and woeful feelings. But Pickle was at the door and all but swooned with happiness to have me back. Dogs were so great. I adored mine and could never resist her enthusiasm.

“Hey, little girl! Hey, my sweet Pickle!” I reached down and scooped her up in my arms and she licked my face clean. “Did you go outside today? Did John and Mayra come and take you to the park?”

Pickle barked and wiggled and barked some more. Apparently, John and Mayra Schmidt, my dog-loving next door neighbors, had indeed taken Pickle somewhere where she found something to roll around with or to challenge because she smelled like shampoo. They were retired and kept a set of keys to my house. Mayra spent a lot of time making note of the personal comings and goings of all our neighbors. She was always peeping through her blinds like Gladys Kravitz on that old television program Bewitched. I loved her to death.

“What did you do, Miss Pickle, to deserve a bath today? Hmm? Did you find a skunk?”

Pickle loved skunks more than any other mammal on this earth. Maybe it was the way they moved in their seductive stealth, low to the ground. They held some kind of irresistible allure. That much was certain.

She barked again and I’d swear on a stack of Bibles that she said yes, she’d been rolling around with a dead skunk. But most dog owners thought their dogs spoke in human words as well as dog-speak. I took her leash from the hook on the wall and attached it to her collar.

“Let’s go, sweetie,” I said, and we left through the front door.

John and Mayra were outside getting into their car. I waved to them and they stopped to talk.

“Hey! How are y’all doing?” I said.

“Hey! Good thing we had tomato juice in the house!” Mayra said. “Our little Pickle ran off with Pepé Le Pew this morning!”

“Pickle,” I said in my disappointed mommy voice.

I looked down at her and she looked at the ground, avoiding eye contact with me.

“So John baptized her with a huge can of tomato juice and then I shampooed her in the laundry room sink.”

Mayra squatted to the ground and held out her hand. Pickle was so happy to be in Mayra’s favor again that she pulled hard against her leash, yanking me forward.

“Thank you! She sure does love you,” I said.

“We love her too. Little rascal. Good thing I went to Costco,” John said. “I stocked up on enough tomato juice to make Bloodies for the whole darn town!”

John was famous for his Bloody Marys but refused to share the recipe. I had tried many times to figure it out and finally decided, because he grew jalapeños, that he must’ve been using his own special hot sauce. And maybe celery seed.

“Well, good! Call me when the bar opens! And thanks again for taking care of my little schnookle. She’s like my child.”

“Ours too!” Mayra said. “I love her to death. She gets me out of the house, and golly, she’s good company.”

“Thanks. I think so too. Come on, you naughty girl, let’s get your human some exercise.”

We walked the streets of my neighborhood, passing one midcentury brick ranch-style home after another. Some had carports and some had front porches but they all had a giant glass window in the living room. Some people parked their boats in the yard and others didn’t even have paved driveways, so the cars were just pulled onto the property.

After my near bankruptcy—which is a story I’ll tell you about how I wound up with boxes and boxes of yoga mats—I was basically homeless. Fortunately for me, my mother had elderly friends who owned this house, which is in the Indian Village section of old Mount Pleasant. My financial disaster coincided with their decision to move to Florida because our climate was too cold for them. I know. That sounds crazy, doesn’t it? But it’s true. Here I am swearing up and down that it’s a sauna outside and someone else thinks it’s too cold. Maybe it’s my age. Hmm. Anyway, I do whatever maintenance there is to be done. I can mow the grass and turn on sprinklers with the best of them.

The house is an old unrenovated ranch constructed of deep burgundy bricks that would never win a beauty pageant. One bathroom is blue and white tile with black trim and the other is mint green with beige. The kitchen is completely uninspiring, and no matter how much I scrub the linoleum kitchen floor it never looks clean. It’s pretty gross, but for the cost of utilities, five hundred dollars a month in rent, and a swift kick to the lawn mower, I have a roof over my head. And one for my daughter when she visits, which is, so far, not much. We’re not speaking and I’ll tell you about that too.

So Pickle and I walked around the block and she sniffed everything under the late-day sun while I looked at other people’s landscaping, wondering how this one grew hydrangea in the blistering heat and why that one’s dead roses weren’t cut back. And I wondered how much longer Kathy Harper could and would hang on to the thinning gossamer threads between her life and the great unknown.

Later on, in the evening after a dinner of salad in a bag and half of a cold pork chop, I called my daughter. She didn’t take the call. I thought about that for a moment and it made me feel worse. I didn’t leave a message because she would know from caller ID that it was me who had called. Then I called my mother. It was either sit on the old sofa and watch Law & Order: SVU until I couldn’t stand it anymore, do sun salutations to relax my body, or call my mother. I sort of needed my mom and some sympathy.

“Hello?”

“Hey, Mom. You busy?”

“Never too busy for my darling daughter! What’s going on?” She put her hand over the receiver and called out. “Alan? For heaven’s sake! Turn that thing down!”

“All right! All right!”

My father yelled from the background and I could see him in my mind’s eye: pushed back in his leather recliner, fumbling with the remote to his sixty-inch television that had its own pocket in the chair opposite the cup holder that held his beer and yet another

pocket for his reading glasses and the latest issue of TV Guide.

“I just wanted to talk for a minute. I had sort of a rough day.”

“What happened? Gosh, it was nice to see you last weekend.”

“You too. Well, we have this really sweet patient at Palmetto House who’s got terrible cancer and it’s like almost the end, you know?”

“Loss has always been hard for you to handle.”

“Well, Mom, death is hard for most people to deal with.”

“You spend too much time dwelling on the negative. Why don’t you join a book club? Or an online dating thing? My book club is coming here this Thursday night. What should I serve them?”

“Oh, just go to Costco and buy a brick of cheese and a box of crackers. And I can’t join book clubs and dating sites because that stuff costs money. You know that.”

“Well, then, do the free things. Go for a walk! Take a book out of the library! Get interesting! Go back to teaching yoga, but in someone else’s studio!”

“Mom! Stop!”

“I’ll tell you, ever since Marianne moved to Denver and you closed your business, you’ve been on a big fat bummer and it’s time for you to snap out of it! All this wallowing—”

“Mom!”

“I’m just saying that you’ll regret your wallowing when you’re my age. You’ll get up one morning and every bone in your body will be killing you. You still have a lot of living left to do, so don’t waste it!”

“Mom! Stop! I didn’t call you to—”

“Here! Talk to your father! Alan! Come talk some sense into your daughter!”

“I’m busy! Just tell her I love her and to quit spending money!”

“Your father’s right. Now, how’s Marianne?”

“How would I know? She never calls.”

“See? There you go again! Why can’t you call her?”

If I told her why Marianne and I weren’t speaking she’d have a heart attack. Somehow, I got off the phone, stared at it, and thought, That’s all he ever says. And she’s always telling me what’s wrong with me! Then I had a terrible thought. What if one of my parents died and the surviving one wanted to live with me? Oh! God! No! I sort of said a blasphemous prayer, petitioning the Lord for my mother to go first because I could tolerate my father’s company without every moment feeling like I was having a deep scaling in the dentist’s chair. But my mother was overbearing and loud and frankly not very nice to me. We would kill each other! But living with Dad would be terrible too. First of all, I couldn’t afford to take care of him. Second, having Dad in my house would obliterate any hope of an intimate life. (Yes, I still had hope.) And third, I might be a nurse but being a personal nurse to my father wasn’t something I could easily do. We were both ridiculously modest and those personal moments of his hygienic routine would be so awkward. On top of it all, he was so set in his ways. He wouldn’t be very happy if the refrigerator wasn’t arranged by size and category or the spice drawer wasn’t alphabetized. Worse, my stupid brother, Alan Jr., and his horrible wife, Janet, would want no part of my parents’ care but they’d want quarterly expense reports on how this arrangement was affecting their inheritance. Oh Lord, please be merciful. Take Carol and Alan St. Clair home to heaven at the very same moment while they sleep.

On that night life seemed dreary, but when the sun came up in the morning, I was filled with irrational happiness. And it proved to be irrational. When I got to Palmetto House I found Suzanne and Carrie with Kathy as she took her final breaths. I cried with them. I couldn’t help it. I’d had no idea she would die so soon.

“Listen,” I said, as soon as I could speak without the fear of sobbing, “I can help if you’d like, with phone calls or arrangements. Just tell me how I can help.”

My words hung in the air for a few minutes until the reality began to sink into Suzanne and Carrie’s minds.

“There’s no next of kin,” Carrie said. “Isn’t that terrible?”

“She wanted to be cremated and she wanted a Mass to be said,” Suzanne said.

“And she didn’t want flowers. She worked at a florist but she didn’t want flowers,” Carrie said. “No flowers at her own funeral. Oh God.”

“But she wanted donations to go to a hospice of your own choosing. I’m sending flowers anyway. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t,” Suzanne said, and collapsed in a chair. Then she sighed so hard that she looked ten years older. “How am I going to handle this?”

I said, “Don’t worry. I will help you. We do this kind of thing here all the time.”

All the Single Ladies

- Genres: Fiction, Women's Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 006213258X

- ISBN-13: 9780062132581