Excerpt

Excerpt

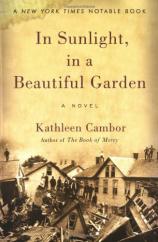

In Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden: A Novel

Chapter One

Memorial Day, 1889

"Nature's law is that all things change and turn, and pass away..."

--Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, Book XII, Number 21

Frank Fallon lay awake after a night of dozing, waking, dozing again. A night of restlessness. A night of decisions.

Each of the two bedroom windows of his house on Vine Street was opened a crack, just enough to let in the first spring air. May nights in the mountains. Air with a freshness to it. As if, finally, it really was going to bring a change of seasons. As if it might bring rain.

Frank's hands were clasped behind his head, his eyes long grown accustomed to the silver-blue darkness. Eight years in this house, he knew it well: the way the floorboard creaked on the third stair, the nighttime sound of brick-and-plaster sighing and settling into itself. There was a porch and parlor, three good-sized bedrooms, a bay window in the dining room. A sycamore tree stood grandly in the back yard, bringing welcome shade in the summer. Wayward branches touched the house possessively. Downstairs, Frank knew, the pies Julia made at midnight sat on the kitchen table, and fat lemons filled a glass bowl, waiting to be squeezed. The iron skillet had already been placed on the stovetop, and on its seasoned surface chicken would be fried as soon as dawn broke, so it had time to cool before the parade and picnic. It seemed an odd thing to him, the idea of picnicking at the cemetery, an old rough blanket spread across the graves.

"But that's exactly the point," Julia always reminded him. Memorial Day, she said. A day for being with them, for remembering the dead.

As if anything about Frank's life allowed him to forget.

From downstairs he heard the sound of the piano. Julia, restless too, trying to ease herself, to pass the night by playing. It was one of the first things he had given her, four years after they were married. He knew that she had had one as a girl in Illinois, a rosewood Chickering, a stylish square piano with intricately carved legs and scrolled lyres. So for four years he'd saved money in a sock. Three days a week he gave up his stop at California Tom's on Market Street, gave up the shot of whiskey that cut so cleanly through the phlegm and grit that always clogged his throat at the end of his shift. For four years, three days a week, he gave up the quick camaraderie with friends, the talk that was impossible on the mill floor, where your very life depended on concentration, focus, where the screech of the Bessemer blow, the wild vibration of machinery drowned out every other sound. Finally, $137 accumulated in the sock. In 1869 it had felt like a small fortune.

The piano was a Fischer upright, used, old already when he bought it. The ivory of the keys had aged to a lineny yellow, and spidery cracks marred most of them, as if a small, light-footed bird had left its footprints as it practiced avian scales. But what they found was that the instrument's age, its years of use, had given it an organic, mellow tone. John Schrader, who sold furniture on Clinton Street, came once a year with his pitch pipe and his small felt sack of tools to keep it tuned. The sound of it, and the image that came to Frank's mind as he lay abed and listened -- of Julia sitting on the round stool, leaning earnestly into the keys, eyes closed to better feel the melody -- still had a power over him. After all this time. After everything that had happened.

Frank Fallon was fifty-one years old. And he planned to march, as he did every year, with the Grand Army Veterans. His uniform from the war was folded on a chair beside the bed. The 113th Pennsylvania. He'd retrieved it from the attic trunk the night before, and when he'd taken the jacket by its shoulders and let the careful folds fall from it, he'd thought he could smell Virginia mud on it. Still. Twenty-six years later. There was a tear in the threadbare right pant leg where a Rebel shell had grazed him.

They would begin gathering for the parade at noon. Stores would be closed today, school canceled. Even the iron works was shut down. It cost a lot to let those furnaces sit idle, a rarely heard-of thing.

He did not think much about the war, except on mornings like this when some ritual holiday required it. It had been foggy at Fredericksburg the night before the battle. The picket lines of the Union troops and the Confederates were so close to one another that conversations could be held between sentinels standing guard. It had snowed throughout December, and Frank remembered how cold his ears were, how he kept rubbing at them with his worn wool gloves as he tried to ward off numbness; how he feared the cold, the dimming of cognition and sensation that came with it. At first he thought that the freezing temperature and exhaustion were going to his head, that he was hearing things, when someone with a harmonica started playing "Dixie.

They'd been camped for days, waiting for pontoon bridges to arrive, so they could be placed across the Rappahannock. Around the campfires loose talk flowed easily, full of bravado. Talk about how quickly Fredericksburg would be taken, bets placed on how many weeks would pass before the war ended. Youth and the rightness of their cause had stirred in Frank and in all his Pennsylvania regiment some ennobled sense that God was on their side, a belief that sound planning and foresight had been part of the strategy that had brought them to this place.

As the Union troops moved toward Fredericksburg...

In Sunlight, in a Beautiful Garden: A Novel

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060007575

- ISBN-13: 9780060007577