Excerpt

Excerpt

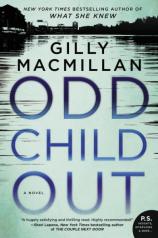

Odd Child Out

THE NIGHT BEFORE

AFTER MIDNIGHT

A black ribbon of water cuts through the city of Bristol, under a cold midnight sky. Reflections of street lighting float and warp on its surface.

On one side of the canal there’s a scrap yard, where heaps of crumpled metal glisten with frost. Opposite, is an abandoned red brick warehouse. Its windows are unglazed and pigeons nest on the ledges.

The silken surface of the canal water offers no clue that underneath it a current flows, more deeply than you might expect, faster, and stronger.

In the scrap yard a security light comes on and a chain link fence rattles. A fifteen-year-old boy jumps from it and lands heavily beside the broken body of a car. He gets up and begins to run across the yard, head back, arms flailing, panting. He runs a jagged path and stumbles once or twice, but he keeps going.

Behind him the fence rattles a second time, and once again there’s the sound of a landing and pounding feet. It’s another boy and he’s moving faster, with strong, fluid strides, and he doesn’t stumble. The gap between them closes as the first boy reaches the unfenced bank of the canal, and understands in that moment that he has nowhere else to go.

At the edge of the water they stand, just yards from each other. Noah Sadler, his chest heaving, turns to face his pursuer.

‘Abdi,’ he says. He’s pleading.

Nobody who cares about them knows that they’re there.

EARLIER THAT EVENING

At the end of my last session with Dr. Manelli, the police psychotherapist, we kiss, awkwardly.

My mistake.

I think it’s on account of the euphoria I’m feeling because the sessions I’ve been forced to attend with Dr. Manelli are finally over. It’s not personal; it’s just that I don’t like discussing my life with strangers.

At goodbye-time she offered me a professional handshake – long-fingered elegance and a single silver band around a black-cuffed, slender wrist – but I forgot myself and went in for a cheek peck and that’s when we found ourselves in a stiff half-clinch that was embarrassing.

‘Sorry,’ I say. ‘Anyway. Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome.’ She turns away and straightens some papers on her desk, two dots of colour warming her cheekbones. ‘Going forward, I’m always here if you need me,’ she says. ‘My door is always open.’

‘And your report?’

‘Will recommend that you return immediately to the Criminal Investigations Department, as we discussed.’

‘When do you think you’ll submit that?’ I don’t want to sound pushy, but I don’t want any unnecessary delay, either.

‘As soon as you leave my office, Detective Inspector Clemo.’

She smiles, but can’t resist a final lecture: ‘Please don’t forget that it can take a long time to recover from a period of depression. The feelings you’ve been having – the anger, the insomnia – don’t expect them to disappear completely. And you need to be alert to them returning. If you feel as if they might swamp you, that’s the moment I want to hear from you, not when it’s too late.’

Before I embed my fist in a wall at work again, is what she means.

I nod, and take a last look around her office. It’s muted and still: a room for private conversations and troubling confidences.

It’s been six months since my therapy began. The aim was to throw me a lifeline, to save me from drowning in the guilt and remorse I felt after the Ben Finch investigation, to teach me how to accept what happened, and how to move on.

Ben Finch was eight years old when he disappeared in a high-profile, high-stakes case, the details of which were plastered all over the media for weeks. I agonized over him and felt personally responsible for his fate, but I shouldn’t have. You have to preserve some professional distance, or you’re no good to anybody.

I believe I have finally accepted what happened, sort of. I’ve convinced Dr. Manelli that I have, anyhow.

I call my boss in the Criminal Investigations Department as I jog down the stairs in Manelli’s building, my eyes fixed on the pane of glass above the front door. Slicked with daylight, it represents my freedom.

Fraser doesn’t answer so I leave her a message letting her know that I’m ready to come back to work, and ask if I can start tomorrow. ‘I’ll take on any case,’ I tell her. I mean it. Anything will do, if it gives me a chance to rejoin the game.

As I cycle away down the tree-lined street where Dr. Manelli’s office is located, I think about how much hard graft it’s going to take to play myself back in at work, after what happened. There are a lot of people I need to impress.

Riding a wave of optimism, as I am, that doesn’t feel impossible.

I’m upbeat enough that I even notice the early blossom, and feel a surge of affection for the handsome, mercurial city I live in.

The light from the gallery spills out onto the street, brightening the dirty pavement.

Tall white letters have been stenciled on the window, smartly announcing the title of the exhibition:

EDWARD SADLER: TRAVELS WITH REFUGEES

In italics beneath, there’s a description of the work on show:

Displaced Lives & Broken Places: Images from the Edge of Existence

The photograph on display in the window is huge, and spot lit.

It shows a boy. He walks towards the camera against a backdrop of an intense blue sky, an azure ocean speckled with whitecaps, and a panorama of bomb-ruined buildings. He looks to be thirteen or fourteen. He wears long shorts, flip-flops and a football shirt with the sleeves cut off. His clothes are dirty. He gazes beyond the camera and his face and posture show strain, because looped across his shoulders is a hammerhead shark. Its bloodied mouth is exposed to the camera. That, and a red slash of blood on the shark’s muscular white undercarriage are shockingly vivid against the ruined architectural backdrop: marks of life, death and violence.

On the Way to the Fishmarket. Mogadishu. 2012, reads the caption beneath it.

It’s not the image that made Ed Sadler’s reputation, that gave him his five minutes of fame, and then some, but it was syndicated to a number of prestigious news outlets, nevertheless.

The gallery’s packed with people. Everybody has a glass in hand and they’re gathered around a man. He’s standing on a chair at the end of the room. He wears khaki trousers, scuffed brown Oxford shoes, a weathered leather belt and a pale blue shirt that’s creased in a just-bought way. He has sandy coloured hair that’s darker at the roots than the tips and thicker than you might expect for a man in his early forties. He’s good-looking: broad-shouldered and square-jawed, though his wife thinks his ears protrude just a little bit far to be perfectly handsome.

He wipes his suntanned forehead. He’s a little drunk, on the good beer, the amazing turnout, and the fact that this night represents the peak of his career but also a devastating personal low.

It’s only four days since Ed Sadler and wife Fiona sat down with their son Noah and his oncologist, and received the worst possible news about Noah’s prognosis. Reeling with shock, they’ve so far kept it to themselves.

Somebody chinks a spoon against a glass and people fall silent.

Head and shoulders above the crowd, Ed Sadler gets a piece of paper out of his pocket and puts a pair of reading glasses on, before taking them off again.

‘I don’t think I need this,’ he says, crumpling the paper up. ‘I know what I want to say.’

He looks around the room, catching the eyes of friends and colleagues.

‘Nights like this are very special because it’s not often that I get to gather together so many people who are important to me. I’m very proud to show you this body of work. It’s the work of a lifetime, and there are a few people that I need to acknowledge, because it wouldn’t exist without them. First, is my good friend Dan Winstanley, or as I should say now, Professor Winstanley. Where are you, Dan?

A man in a button down blue shirt, and in need of a haircut, raises his hand with a sheepish smile.

‘Firstly, I want to thank you for letting me copy your Maths homework every week when we were at school. I think it’s a long enough time ago that I can safely say that now!’ This gets a laugh.

‘But, much more importantly, I want to thank you for getting me access to many different places in Somalia, and in particular to Hartisheik, the refugee camp where I took the photographs that my career’s built on. It was this man Dan who took me there for the very first time when he was building SomaliaLink. For those of you who don’t know about SomaliaLink, you should. Through Dan’s sheer bloody-mindedness and talent it’s grown into an award-winning organisation that does incredible work educating and rebuilding in projects throughout Somalia, but it was founded almost twenty years ago with the more humble objective of fostering links between our city and the Somali refugee community, many of whom came to Bristol via Hartisheik and its neighbouring camps. I’m very proud to be associated with it. Dan, you’ve been my fixer for as many years as I can remember, but you’ve also been my inspiration. I never could contribute much in the way of brains, but I hope these images can do some good in helping to spread the word about what you do. Taking these photographs is often dangerous, and sometimes frightening, but I believe it’s necessary.’

There’s a burst of clapping and a heckle from one of his rugby friends that makes Ed smile.

‘I do this for another reason too, and that, most of all, is what I want to say tonight…’ he chokes up, recovers. ‘Sorry. What I’m trying to say is how proud I am of my family and how I couldn’t have done this without them. To Fi, and to Noah, it hasn’t always been easy – understatement – but thank you, I’m nothing without you. I do all this for you, and I love you.’

Beside him, his wife Fiona’s face crumples a little, even as she works hard to hold it together.

Ed scans the room, looking for his son. He’s easy to find because his friend Abdi is beside him, one of only four black faces in the room, apart from the ones in the photographs.

Ed raises his bottle of beer to his son, salutes him with it, and enjoys seeing the flush of pleasure on the boy’s cheeks. Noah raises his glass of coke in return.

About half the people in the room say, ‘Awww,’ before somebody calls out: ‘Fiona and Noah!’ and everybody raises their glasses. The applause that follows is loud and becomes raucous, punctuated with a couple of wolf whistles.

Ed cues the band to start playing.

He steps down from the chair and kisses his wife. Both are tearful now.

Around them, the noise of the party swells.

While Abdi Mahad is at the exhibition opening with his friend Noah, the rest of his family are spending the evening at home.

His mother, Maryam, is watching a Somali talent show on Universal TV. She thinks the performances are noisy and silly, but they’re also captivating enough to her hold her attention, mostly because they’re so awful.

The show is her guilty pleasure. She laughs at a woman who sings painfully badly and frowns at two men who perform a hair-raising acrobatic routine.

Abdi’s father, Nur, is asleep on the sofa beside his wife, head back, and mouth open. Maryam glances at him now and then. She notices that he’s recently gone a little greyer around the temples, and admires his profile. He doesn’t have his usual air of dignity about him, though, because he’s snoring loud enough to compete in volume with the shrill presenters on the TV. A nine-hour shift in his taxi followed by a meeting of a local community group, and a heavy meal afterwards with friends, has knocked him out as effectively as a cudgel.

As the TV presenters eulogize over a rap performance that Maryam judges to be mediocre, at best, Nur snorts so loudly that he wakes himself up. Maryam laughs.

‘Bed time, old man?’

‘How long have I been asleep?’

‘Not too long.’

‘Did Abdi text?’

‘No.’

They’ve been worried about Abdi going to the photography exhibition. They know the subject of the show is refugee journeys, and they know that some of the images that made Edward Sadler famous were taken in the refugee camp that they used to live in. These things make them uneasy.

Abdi never lived in the camp. Nur and Maryam risked their lives to travel to the UK to ensure that he never had to experience a life that looked the way theirs did once everything they’d ever known unspooled catastrophically and violently in Somalia’s civil war. Both of them were torn from comfortable, educated homes, where James Brown played on the turntable some evenings, and Ernest Hemingway novels sat on the bookshelf amongst Italian books, where daughters were not cut, and children weren’t raised to perpetrate the divisive clan politics that would soon become lethal.

Nur and Maryam tried hard to dissuade Abdi from going to the exhibition, but he wasn’t having any of it.

‘Don’t wrap me in cotton wool,’ he said, and it was difficult to argue with that. He’s fifteen, confident, clever and articulate. They know he can’t be sheltered forever.

They reasoned eventually that if the extent of his curiosity about their journey as refugees was to visit an exhibition, then perhaps they would be getting off lightly, so they let him go, and told him to have a good time.

Maryam turns the TV off, and the screen flicks to black, revealing a few smudgy fingerprints that make her tut. She’ll remove them in the morning.

‘Are you worried?’ She asks Nur.

‘No. I wasn’t expecting him to text anyway. Let’s sleep.’

As her parent go through the familiar motions of converting their sofa into their bed, Sofia Mahad, Abdi’s sister, is sitting at her desk in her bedroom next door.

She’s just received an email from her former headmistress, asking her if she would be willing to revisit the school and give a speech to sixth formers on careers day.

Sofia’s twenty years old, and in her second year of studying for a midwifery degree. She’s never done public speaking before. She’s shy, so she’s avoided it like the plague. She’s flattered by the invitation, though, and especially by the sentence that describes her as ‘one of our star pupils’.

‘Guess what?’ she calls out to her parents, ‘I’ve been asked to give a speech!’

She takes out one of her earbuds so she can catch their response, but there isn’t one. They obviously haven’t heard her. She’ll tell them face-to-face later, she thinks, when she can enjoy seeing the proud smiles on their faces.

She rereads the email. ‘One thing that might really interest our Year 13s,’ the headmistress writes, ‘is hearing about what inspired you to become a midwife.’

Sofia does what she usually does when she’s considering something. She gets up and looks out of the window. Outside she can see a small park that’s empty and quiet, and a large block of flats on the other side of it. The un-curtained windows reveal other people’s lives to her, lit up in all shades from warm to queasy neon, some with a TV flicker.

She knows exactly what inspired her: it was Abdi’s birth. The problem she has is that she’s not sure if she can write a speech about it, because nobody in her family has ever talked openly about what happened that night. Her mother tells a very short version of the story of Abdi’s birth: ‘Abdi was born under the stars.’

Sofia also knows that’s not the whole story, because she remembers the night in vivid detail. Like all of her memories of Africa, it’s intense. She sometimes thinks of that part of her life, the part before England, as a kind of hyper-reality.

Abdi was born in the desert, and Sofia can picture those stars. They roamed the sky in great cloudy masses. They looked like cells multiplying under a microscope. They cast their milky brightness down once the truck had stopped and the headlights were extinguished.

The men didn’t let Maryam out of the truck until her time was very close. She had been laboring for hours, crammed into the flatbed with the others, and she continued to labour in the Saharan emptiness. There were no other women to help, so it was Sofia who knelt and cradled her mother’s head, her fingers feeling the sweat on Maryam’s cheeks, and the clench of her jaw. Nur knelt beside them and delivered the boy with shaking hands.

Sofia remembers the feel of the stones digging into her shins, her knees and the top of her feet. She remembers how the light from the stars and the crescent moon made the shifting surfaces of the sand dunes shimmer. She thought that their brightness drew Maryam’s cries up to the heavens and coaxed the baby from her body.

The smugglers spoke harshly to Maryam, telling her to be quiet, and to be quick. Each of them had a third leg to their silhouette, made from a long stick, or a gun. Then leaned on them impatiently, propped up by violence, and hungering for speed, and for maximum profit from their human cargo.

Sofia remembers how the blade of the knife glinted in the torchlight when the men severed Abdi’s cord. ‘Hurry! Get back in the truck!’ the men said, and their eyes cast threats of abandoning Maryam there if she didn’t obey. Minutes later she delivered the afterbirth obediently, wet and bloody onto the parched ground, and the wind speckled it with sand.

Back in the truck, the faces of the other passengers were swaddled against the sand and wind. Maryam passed out: heavy body sweated soaked, and clutching blood-dark material between her legs. Nur held her and his breathing shuddered as the engine revved. Sofia cradled her new brother. She kept him warm. She put her face up close to the baby’s and gazed at him. In the starlight she examined his sealed up eyes, his damply soft flesh and hair and she knew that she loved him.

As the truck swayed and skidded on the track through the desert, that thought brought her a feeling of warmth, even though she was very afraid.

Sofia breathes in suddenly – almost a gasp – and it snaps her out of her reverie. She types an email to her headmistress thanking her for the invitation and telling her she would like to give it some thought.

When that’s done she lapses once again into thinking about Abdi, and how strange it could be to be born between places, as he was, under the gaze of smugglers and thugs. Where would you belong, really? How would it affect you, deep in your bones? Would you know that threats had torn you from your mother’s sweaty, terrified body?

She doesn’t dwell on it too hard, though, because she’s soon distracted by the buzz of her social media notifications, and all the distractions of the present.

Sofia doesn’t think about Abdi again that night. Nor do her parents, apart from a brief discussion once they’re tucked under the duvet, when they sleepily debate whether Abdi should give up Chess Club to make more time to study exams he’s due to take this summer. They have so much hope that he will get the results he needs to apply to a top-rank university.

All is quiet in the household over night. It’s in the frigid early hours of the morning that the buzzer to their flat begins to ring repeatedly, long and loud, before dying away like a deathbed rattle as the battery fails. Nur climbs out of bed to answer it. He’s hardly awake enough to be on his feet.

‘Hello?’ he says. He can see his breath.

In response, he hears a word that he learned to dread at an early age: ‘Police’.

Odd Child Out

- Genres: Fiction, Mystery, Psychological Suspense, Psychological Thriller, Suspense, Thriller

- paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0062476823

- ISBN-13: 9780062476821