Excerpt

Excerpt

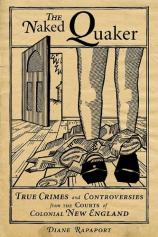

The Naked Quaker: True Crimes and Controversies from the Courts of Colonial New England

Chapter 2

COUPLING

Puritan prohibitions could not curb sexual attraction. Many New Englanders landed in court for pre marital dalliance, adultery, and other acts of love and lust. Although it is difficult to choose --- the court records offer so many stories about seventeenth-century couples who could not keep their hands off each other --- the following three stories are typical.

"The Scottish Rogue" takes us to a Connecticut ironworks village where a young man defends himself against charges of sexual misconduct. In "The Wandering Wife," a teenage girl attracts and marries an older man but finds herself not ready to settle down. The final story in this chapter, "The Rhode Island Runaway," is a poignant look at a doomed love affair and the unexpected redemption that follows.

The Scottish Rogue

The word rogue sounds quaintly comic to the modern ear, a seldom-used term more likely to provoke laughter than indignation. In seventeenth-century New England, however, calling someone a rogue was no joke. Rogue meant liar, villain, or scoundrel --- usually with a hint of sexual misbehavior --- and it was the worst sort of insult, liable to trigger a fistfight or a slander suit. Accused rogues often wound up explaining themselves to a judge or jury, and the court records reveal amusing --- and sometimes shocking --- details of life in long-ago New England. One case from colonial New Haven offers a particularly colorful glimpse into the bawdy culture of a Connecticut ironworks village, where a Scotsman, Patrick Morran, feuded with the Pinion family.

When Patrick first arrived in Massachusetts with a shipload of Scottish war prisoners in 1652, he occupied one of the lowest rungs on the Puritan social ladder, little better than a slave. (Apparently, he was one of the Scots captured in 1651 by Oliver Cromwell’s troops at the Battle of Worcester, near the end of the English Civil War.) As servant to Oliver Purchase, clerk of the Hammersmith Ironworks in Lynn, Patrick became acquainted with the family of a carpenter, Nicholas Pinion. Pinion was no gentleman --- his penchant for drunken violence often landed him in court --- but he worked for wages at Hammersmith and had enough clout to "rent" Scotsmen from the ironworks company. By the mid-1600s, Patrick and Nicholas had found new work at a small forge along East Haven’s Furnace Pond (today’s Lake Saltonstall in Connecticut). The move brought a curious role reversal for the two men. Patrick had earned his freedom and was beginning a career as clerk-paymaster of the East Haven ironworks, his astonishing good fortune probably due to literacy, bookkeeping skills, and good relations with his former master. Nicholas and his family now found themselves uncomfortably subordinate to Patrick, forced to take their orders, and wages, from a former Scottish servant.

Soon the Pinion women were calling Patrick a "Scotch rogue," but whether he deserved the epithet is difficult to judge. The surviving court evidence suggests a Pinion vendetta against the Scottish ironworks clerk, but Patrick’s own poor judgment surely contributed to his legal troubles. Sorting out the truth was not easy for the New Haven magistrates when Patrick went on trial in January 1665, accused by Elizabeth Pinion of "attempting to Violate the Chastity of [her] two daughters."

Fifteen-year-old Hannah Pinion furnished lurid testimony. "One rainy day," Patrick followed Hannah on an errand and offered her a pair of gloves, "if she would come to the furnace with him and let him lie with her." Hannah rejected this proposition, telling Patrick that she would not do what he asked "for many gloves." Patrick persisted, promising to wait for her at the ironworks and to leave a signal on the furnace bridge. Three weeks later, Patrick allegedly tried again, raising the stakes by offering Hannah gloves and a pair of stockings, his new signal to be "a great stone . . . upon the black stump by the house." She still refused. When Hannah went to Patrick’s room one Friday night --- purportedly to ask him for a pound of sugar --- he sweetened the offer of gloves with a silver shilling, too, if she would lie with him. Apparently sure of success this time, he brandished the shilling, took her in his arms, and flung her on the bed, but she threatened "if he would not be quiet she would call out to the folk below, and so he set her down again."

Elizabeth Pinion supported her daughter’s testimony, recounting several times when she sent Hannah to the company store (which Patrick managed) for items such as gloves, stockings, liquor, or sugar, and Hannah returned home empty-handed. Patrick would not dispense these goods, Hannah told her, unless he could "have the use of her body in an unclean way."

Ruth Moore, Hannah’s older sister, also testified. When she learned from Hannah "how Patricke inticed her," Ruth arranged to stop by the forge on one of the appointed nights herself, taking the precaution of asking a neighbor, Thomas Luddington, to follow her to witness what might happen. Ruth found Patrick standing at the shop door by the furnace bridge, and after some teasing banter, she accepted his invitation to "drink a dram of the bottle." Then he invited Ruth into the shop, making such "immodest and shameful" suggestions that Ruth was "ashamed to speak [of] it" in court. According to Ruth, only Luddington’s arrival on the scene prevented Patrick from taking improper advantage.

When the next witness took the stand, however, the case against Patrick began to unravel.

Excerpted from The Naked Quaker © Copyright 2012 by Diane Rapaport. Reprinted with permission by Commonwealth Editions. All rights reserved.

The Naked Quaker: True Crimes and Controversies from the Courts of Colonial New England

- hardcover: 160 pages

- Publisher: Commonwealth Editions

- ISBN-10: 1933212578

- ISBN-13: 9781933212579