Excerpt

Excerpt

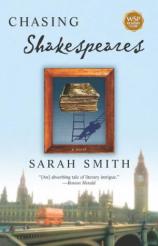

Chasing Shakespeares: A Novel

That day I was just about to lose my vocation, my job, my good sense, probably my mind, but what I thought I was losing was Mary Catherine O'Connor.

"You shouldn't go," I said to Mary Cat. We were in my truck, stuck in traffic on the Southeast Expressway on the way to Logan; I had one more chance to tell her all the things she hadn't listened to before. "You don't want to do this, it isn't your life."

"They want me," Mary Cat said. "I'll be of use, Joe."

"You are of use -- " I ground gears, cut off a Toyota that wanted to pass me on the right, and switched into the airport lane. One thing about driving a pile-o'-shit truck with the truck bed full of broken windows, people get out of your way.

"This is the way God means me to be of use."

She was putting on her gentle voice, settling into being a postulant already. She'd worn her worst clothes for the trip, tired-out jeans and a faded orange kerchief over her red hair, and that red parka I hoped she'd have taken out behind the barn and shot. Mary Catherine O'Connor, the most beautiful girl in Boston, was trying to look plain.

She wasn't my girl. Just my friend, my study buddy, my co-researcher at the Kellogg. I'd met Mary Cat my first week of graduate school. We'd been the only two students in Rachel Goscimer's seminar on Elizabethan research, me and this stunning red-haired girl. She wore no makeup at all and cheap striped jeans and a faded sweater and a patched, stained, feather-leaking red parka that looked like she'd got it out of the charity bin at Saint Mike's. But I'd been pretty taken with her, and I'd asked her out before I realized the kerchief over her curls and the little gold cross she wore meant she wanted to be Sister Mary Catherine.

"You were the one who applied to the Society of Mary," I said. "God didn't fill out the application. Mary Cat, you can tell them no. At least you should be applying to someplace you can use your education, not making coffee for pissy old drunks," I said.

I didn't say she should be applying to a teaching order. And she didn't have to say what we both knew, they'd never let her teach. But there was a silence while we both didn't say that. I negotiated the tunnel ramp. Traffic was bad in the tunnel and we crawled forward, breathing fumes, watching a futile road of red brake lights in front of us.

"You'd stay if there were anything good in the Kellogg Collection," I said.

"I wish I weren't leaving you with the Kellogg."

"I don't mind that, I can do the rest of it alone. But you'd stay, wouldn't you?"

"I have to do this," she said.

"You would stay."

She didn't say anything, just nodded, not agreeing, just showing she'd listened.

"Then don't you see you're not going because God called you, you're going because you're pissed off?"

"That's ridiculous, Joe," she said hotly, not like a nun at all.

"Just wait a while," I said. "Finish your Ph.D."

I carried her backpack from the parking lot and waited with her while she stood in line for check-in. I hoisted her backpack up on the scale to be weighed, watched while the baggage handler tagged it, LHR, London Heathrow, and looked after it as it slid away. She was going. She was going after all. We walked together toward the security check.

"Keep in touch," I said. "Write me a letter, e-mail, something."

"If I can," she said. "Come to visit in London. Sister Mary Joseph says we've plenty of room for guests."

"I sure will come to London. I'll make you write your thesis," I said. "I'll stand at the door, frighten the winos, make them give you some peace. Get Sister Mary Joseph to give you afternoons off, go to the British Library."

She laughed at that.

"I mean it. You're too good to throw away. Please."

She looked up directly at me, clouded green eyes. She took my hands in both hers. Hers were as rough as mine, not a scholar's hands. "All I can do is go where I'm needed," she said. "I can't bargain what I'm needed for. Joe, you're the researcher, you'll find something in the Kellogg, I know it. I'll be praying for you. And when you do, and you have your first book planned and you're on your traveling fellowship, come to see me on Docklands Road and tell me all about it." She hugged me, a quick nunlike hug. "I've got to go now."

I watched her go through the security gate. Then I went out and found my truck in Central Parking, and kicked the tires once or twice, and sat in the cab and picked off the seat a couple of feathers from her red parka. Go figure; the feathers were what almost made me cry. I swore a while to make myself feel better.

Didn't help a bit.

My grandfather farmed. My father came back from the Vietnam War, sold the farm, bought a hardware store. Me? I wanted to write Shakespeare's life.

I remember reading my first lines of Shakespeare. I was nine years old and had the measles. Itched like a wool sweater. I'd read everything in the house, comics, an old Reader's Digest Condensed Book, Dad's supply catalogs, and there was only one book left, a big ratty falling-apart paperback mended with duct tape. It fell open to Macbeth.

Double, double, toil and trouble...

If you're a kid, two plays can start you on Shakespeare, Macbeth or Hamlet. I goggle-eyed my way through witches and murders and ghosts, having as much fun as if it was Stephen King. And then I got to the end of the play. Lady Macbeth is dead, and Macbeth is so torn up he can't even realize it, all he can do is wish it were sometime else when he could sit down and work up to grieving her. And he realizes he's got forever because she'll be dead forever.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow --

That speech took me somewhere a nine-year-old kid had no business going. It was a place that could swallow me up and not even notice. Like the woods beyond where the roads go, where grownups get lost. I put my head down on my arms and cried, and it wasn't just I had the measles, I knew that place was out there. But I knew, when I got there, I'd recognize the place and I'd know a man who had been there too.

That was the first Shakespeare I really read. I've never forgotten. And from then on, I guess, Shakespeare was something that was going to happen to me, a part of my future, something that was going to happen when I grew up.

It must have been then I started wondering who Shakespeare was, but I never thought about Shakespeare being my work until ten years later. It was the summer after my junior year in college. I'd just begun installing windows to get money. Window installers go through jeans like toilet paper; I was picking up a pair on the cheap in the Salvation Army in Montpelier, saw a paperback, Young Man Shakespeare, bought it because it was about Shakespeare. There's a divinity that shapes our ends. I read it that evening, bouncing around in the back of the truck with a houseful of old windows. I read about Shakespeare in Stratford and I looked up, saw the sunset light through the road grit and the wind, and Donny and Ray Lavigne were joking at me from the cab of the truck, sharing a beer and seeing who could belch longest. Some book you got, Joe, ain't even got tits and ass on it, what's it good for?

Shakespeare. A guy eighteen, already married, I knew guys like that, a few years later they were pumping gas and the best thing in their lives was their kid was playing Little League. But Shakespeare? He was going to go places other men couldn't even imagine. What happened?

How could you not want to know?

So I wrote Roland Goscimer and told him how much I'd liked Young Man Shakespeare, and got a letter back from Rachel Goscimer; and a year later I walked into Rachel Goscimer's seminar on Elizabethan research, and the only other person in it was a smart, fine-looking girl named Mary Catherine O'Connor.

And then Rachel Goscimer had pulled off a coup and got Frank Kellogg's collection of Elizabethan books and manuscripts, and got all of us the right to publish what we found there. But Rachel Goscimer was dead now, and Roland Goscimer was mourning her, and Mary Cat was in London washing winos' feet, so there was nobody left to face the Kellogg but me.

That day I found six forgeries in the Kellogg Collection, which was a record, but not by much.

I had been working with the Kellogg Collection seven months, and at four in the afternoon on the Ides of March I cataloged my three hundred and fifty-seventh forgery; do the math, that's about a fake and a half a day. Opening one of Frank Kellogg's archival envelopes had started to be like putting your hand into the potato barrel and feeling something furry. You might not know what it was, but you knew it wasn't good.

The Kellogg Collection had its own room in the basement of Northeastern. The computer I was using to catalog it was brand-new. The room was new; the whole Northeastern library was new. The big library exhibit so far was an elephant tusk carved into a hundred Buddhas. The Kellogg Collection had been going to be the second big thing, Northeastern's exhibit for the new millennium.

The Kellogg wasn't all bad; no collection is. Kellogg's aunt had bought Elizabethan costume books, and we were going to be pretty well set on Elizabethan history and politics. But that wasn't what we'd expected from the Kellogg. We'd wanted the manuscripts.

And we had 'em, all right. Faded brown ink, ragged paper, letters sealed with ribbon and with fragments of wax. Boxes of them. Letters from Mary Queen of Scots, from Queen Elizabeth. Six Shakespeare letters, one with a sonnet attached. I was scanning them all, for the catalog, and I'd started to amuse myself by printing them out and posting them on the bulletin board in the room. The Wall of Sin.

I tacked the printout of the latest forgery to the board and stared at the rest. Shakespeare, Jonson, Marlowe, Queen Elizabeth, Sir William Cecil, Mary Queen of Scots, the Duke of Norfolk.

Frank Kellogg, the Midwest Discount King. At the Warrenton County Agricultural Fair in 1895, his mama Mary Steuart (age thirteen) learned from a gypsy that she was the direct descendant of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots. Ignoring clues to the contrary, for instance that her father wasn't king of England, Mary married a department-store heir and started collecting. She lassoed her husband and sister in, and eventually her boy Frank, and they bought everything they could find on Mary Stuart, Queen Elizabeth, and the Catholic-Protestant wars.

For years people had talked about that collection. Passed on rumors about it. Wanted it. Sure, the Kelloggs had been a little odd; sure, nobody had really seen the manuscripts; but a collection of Elizabethan materials going back a hundred years? There had to be amazing stuff.

Rachel Goscimer had got the Kellogg for Northeastern. Even the last time she'd been in the hospital, dying, she'd worked on Frank Kellogg. "Dear Mr. Kellogg," she'd whisper, sitting up in bed holding the phone, "we have two of the most marvelous young scholars here, they are so eager to write about your collection!" Kellogg died a month before she did, so she'd known he'd left the collection to Northeastern; but she never knew what was in it, so she died happy.

The difference between the right word and the almost right word, Mark Twain said, is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning. For seven months I'd been hearing thunder and swatting bugs.

And Mary Cat had been right here with me; but now she'd given up. I wondered whether I ought to give up too. But at least Mary Cat was going to what she thought she wanted; and what I wanted would have been this, if a word of it had been real.

I stood glaring at the Wall of Sin. William Shakespeare writing to Richard Field about printing Venus and Adonis. The Earl of Southampton writing to Shakespeare, thanking him for a sonnet. Queen Elizabeth sending ten pounds to Shakespeare. Biographies are lives made comprehensible, beginnings, middles, ends, solid as post and beam. Forgery is rot in the beams. Forgery is a bulldozer, an ax, a fire. Forgery kills the heart. Forgery makes good Catholic researchers decide they're wasting their time in graduate school and go off to London to serve the poor. I started pulling the printouts off the board one by one, balling them up and seeing if I could hit the wastebasket with them. I was doing okay, getting myself a little Antoine Walker action going, and if I was missing Mary Cat I was doing pretty good at fooling myself I wasn't, when the phone rang.

For a moment I thought she'd missed the plane, she'd changed her mind. But the voice on the other end of the phone was no one I recognized.

"Is this like Joe Roper?" Breathy Marilyn Monroe kitten voice. Whoever it was, she was on a cell phone; the connection had that drainpipe sound. But the voice went with the March weather, rainy, a little sweet, with an undertone of spring.

"Yeah."

"This is Posy Gould? Roland Goscimer told you about me? I knew Frank Kellogg? I want to see the Kellogg Collection?"

I looked across at the half-bare bulletin board. Goscimer was sending someone here?

"I like just finished my orals in English? And I'm going to work on Sir William Cecil?"

In the Kellogg Collection? A grad student. She sounded like a Valley Girl but she'd pronounced Cecil right, Sissel. Cecil was a funny choice for a thesis in English. Was she a biographer too?

"You knew Frank Kellogg?" I asked. That would mean she was rich. Something in her voice sounded that way, like private schools and private jets.

"Frank was just like sort of a friend of Daddy's."

Yup, rich.

"Are you going to be at Goscimer's reading?" she asked. "I'll meet you. What do you look like?"

Um. "Brown, brown, glasses, six feet, built like I used to play hockey. How'll I know you?"

"Oh," said Posy Gould. "You'll know me."

I hung up the phone and called Goscimer. "Posy Gould?" I said.

Goscimer's chuckle quavered over the line. "Ah, Miss Gould."

"Has anybody told her what's in the Kellogg Collection?"

"Pride goeth before a fall, Joe, and an upright spirit before destruction. I don't believe I mentioned it. Miss Gould has been very persistent."

"Why'd she want to see the collection?"

"Her friend Frank Kellogg told her there were amazing things in it. Miss Gould is rather amazing herself. She is supposed to have a tattoo of Queen Elizabeth's signature, Joe. Somewhere upon her body. Do young people ever still say 'hubba hubba'?"

"Hubba hubba," I said dutifully. "Is she any good as a researcher?"

"A tattoo," Goscimer sighed, as if that explained everything about Posy Gould.

Over the phone there was a moment's silence.

"I'm sorry," Goscimer said. "About the collection, I mean. About Mary Catherine's leaving. I'm -- so very sorry to leave you with it, Joe."

"Well," I said, "maybe this Gould girl wants to help me catalog."

"You could do an edition for your thesis. Editions are very useful and respectable."

"I'll give it thought, sir."

I hung up. An edition, I thought. Editions are new publications of old plays or poems, all cleaned up and accurate, with up-to-date footnotes and a scholarly introduction. A good edition would only take a year. But editions were for people who didn't have anything to say or couldn't prove it, so they collated copies and variants and spaded the ground for better scholars. An edition wouldn't get me a job, wouldn't put me on the path to being one of Shakespeare's biographers.

What I'd been looking for in the Kellogg was a new sense of Shakespeare, a new way of understanding him and his times. What I'd dreamed of finding was not a manuscript (well, I'd dreamed) but a new fact. It could happen, it had happened; the Wallaces had gone through the entire Public Records Office and found Shakespeare's deposition in the Mountjoy case. If the Kellogg Collection had really been about Mary Stuart, there might have been something about Shakespeare and the Catholics.

I wasn't going to find anything.

I sat down again at the computer, opened a new catalog record, reached into the box to get the next item, and brought up -- shit -- one more of the familiar slick archival envelopes.

Inside the envelope was another envelope, a sheet of old parchment folded over itself in the eighteenth-century way. The seals that closed the envelope were missing, nothing left but a bloodstain of reddish-brown wax. There was no address either, only an inscription in a dashing loose hand. "An abominable Forgery." Probably faked, though for a change it didn't look it.

I unfolded the parchment and had the letter in my hand.

It smelled; that was the first thing I noticed. Not a stink but strong: the smell of wood fires, of dust, of horses, of smoke and fog and the hard-to-reach neglected shelves in libraries: the smell of centuries. The paper was rag stock, thick and strong, but the ink was oak-gall, which is acidic; it had browned the paper and on one corner, where the ink had blotted, the words had been eaten away. The hand was piss-poor, small and barely legible; the lines straggled down the page in waves of effort, painful regular letters becoming tired shakes. Sweat from the writer's palm had blurred the ink.

I could put my hand on the paper and see and feel the guy writing it, four hundred years ago.

And halfway down the page was a phrase I could make out, "the plotte of ye Playe."

This is it, I thought, this is something, and turned it over to look at the signature.

Ah, fuck, screw it. I stood up, stomped around the room, kicked the desk. Shit.

William Shakespeare.

Up on the wall, screwed on the wall the way they do with benefactors' pictures, hung a photograph of Frank Kellogg. I thought pretty seriously about putting a pry bar through the glass, unscrewing the frame, and throwing Frank Kellogg out with the trash. It was a good warm healthy thought.

And then I dug the printouts of the other Shakespeare forgeries out of the trash and looked at them together with this one. This one that had felt real to me.

Most forgeries don't hold up five minutes; the paper's wrong, they're written in ballpoint, something. They're short, because the forger doesn't want to deal with facts. "Let Mrs. So-and-so pass to visit her son, A. Lincoln," that sort of thing. They're easy to read, because what's the point of a forgery you can't read?

This letter was written in Elizabethan secretary hand, the fast script that sixteenth-century professional writers used. Secretary hand, even faked, is a bastard. I could read the salutation, something about a horse, and halfway down the first page, a joke. "Whence cometh thy name, knowest thou? -- Marry, my lord, from my father, says I."

One sentence I could make out well enough. It was probably the one I was meant to read.

"Those that are given out as children of my brain are begot of his wit, I but honored with their fostering."

A letter from Shakespeare, saying he didn't write the plays.

When I was a kid, I used to go out in the woods around East Bradenton and try to find the old deserted farms. Ruins of a chimney in the grass, a hole filled with stones, the skeleton of an old truck, bits of stone wall in the underbrush. By the wall, fragments of a blue-and-white cup. I'd wonder who threw the cup against the wall and why. Ruins were like lives, but with sunlight and smells and dirt to dig in. The more mysterious it was, the more fun.

A clever forger would make his forgeries like a deserted house or a rusty truck in the woods. Mysterious, full of facts you couldn't check and could only imagine about. This letter would be a puzzle for someone, and make someone want to boast and show it off and make a fuss over it, and be tempted to think it wasn't a forgery.

I was dealing with a clever forger.

Shit.

And all those nuts who thought Shakespeare didn't write Shakespeare? They'd love this.

I took off my glasses and squinted at the letter.

It was addressed to the poet Fulke Greville. Cute. Greville had been a courtier under Elizabeth and James I. Lived near Stratford. Not the first person you'd think of; well-documented; somebody the forger could find out about. The letter's first paragraph said something barely legible about Salisbury dying. Good detail; Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, was Greville's worst enemy. The joke was wrong for Fulke Greville; he was a melancholy, serious man, not the sort you'd send old jokes to. But that mistake wouldn't prove this letter was a forgery.

There are scientific methods to tell whether a letter is a forgery or real. Most of them involve chemistry and time and money. I had the others, and I tried them. I smelled the paper, trying to sniff chemicals or new ink under the smoke and dust and cinnamon. I magnified it letter by letter with the loupe. I scanned it, both sides, and zoomed in on individual words, individual letters, trying to decide whether the trembling in the handwriting was forger-shakes or an old man's palsy. The signature didn't copy any of the six Shakespeare signatures, but looked similar. The formation of letters was like Hand D's in More, which could be Shakespeare's hand. The signature had a flying tail. The writing was small -- forged handwriting often is -- but Shakespeare's real signatures are small too. I held the paper up to the light to check for maker's marks or distinctive wirelines: nothing. The ink wasn't blurred except from "Shakespeare's" sweaty palm, so this wasn't new ink on old paper unless the paper was coated somehow. Most coatings show up under UV; I dug in the closet for the UV light before remembering Roy had borrowed it.

Shit again.

Roy Dooley was my boss on this job, one of the research librarians at Northeastern and now librarian of the Kellogg Collection. It had been a big promotion for him. The first few days he'd fussed over the unpacking of every box, every item. And then he'd gone off and cried.

Roy wanted something good to come out of the Kellogg.

What was he going to do with this?

I put the letter and envelope and all in the middle drawer of the desk and went to find Roy.

He was in his office, just leaving for the night. "Hey, Joe, what's up?"

"Same old stuff; a copy of Baker's Shakespeare Commentary, some more costume books -- Roy, do you have the UV light?"

"Karen from Circulation has it, she's having a Grateful Dead theme party." One of the problems with being a biographer is you start thinking that way about people you know. Roy looks like a hamster; Karen is a babe; Roy adores Karen. I knew that Roy would wear a tie-dyed T-shirt to Karen's party, go around all night saying "Groovy," get pissed on Bud, tell Karen he loved her, and spend Sunday wishing he was dead.

Roy was the kind of guy that needed to make an impression.

"Anything interesting?" Roy asked hopefully.

I could have said right then, standing at the door of his office, "Roy, I've got this fucking letter," and maybe everything would have come out fine. I was only imagining things about Roy; it was the Roy I'd made up I didn't trust. Biography does you wrong; you use imagination to fill in what you don't know, but then you go on as if it's true. So the life you're writing always is your own. You forget that.

"Nah," I said finally. "But bring back that UV light Monday?"

My computer had a CD burner and a local hard drive, where I'd been storing the scans. I copied the scans of the letter onto a CD, wiped them off the disk, put the original letter and its covering back in Kellogg's archival envelope, and locked the whole thing in the center drawer of the desk, wishing I had Mary Cat to talk it over with.

I was set up for Posy before ever I met her.

Chasing Shakespeares: A Novel

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Washington Square Press

- ISBN-10: 0743464834

- ISBN-13: 9780743464833