Excerpt

Excerpt

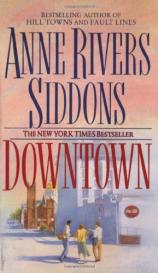

Downtown

The first thing I saw was a half-naked woman dancing in a cage above Peachtree Street.

It was a floodlit steel and Plexiglas affair hung from a second-story window, and the dancer closed her eyes and snapped her fingers as she danced in place, in a spangled miniskirt and white go-go boots, moving raptly to unheard music. It was twilight on the Saturday of Thanksgiving weekend, 1966, when we reached Five Points in downtown Atlanta, and the time-and-temperature sign on the bank opposite the dancer said "6:12 p.m. 43 degrees." The neon sign that chased itself around the bottom of the dancer's cage said "Peach-a-Go-Go."

"Holy Mother of God, look at that," my father said, and slammed on the brakes of the Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser that he loved only marginally less than my mother. Or rather, by that time, more.

I thought he meant the go-go dancer, and opened my mouth to make reassuring noises of shock and disapproval, but he was not looking up at her. He was looking at a straggling line of young Negro men and women walking up and down in front of what I thought must be a delicatessen. There was an enormous pickle, glowing poison neon green, over its door. It was raining softly, blending neon and auto-

mobile and streetlights into a magical, underwater smear. The walkers seemed to swim in the heavy air; they carried cardboard placards, ink running in the mist, that read "Freedom Now," and "We Shall Overcome." My heart gave a small fish-flop of recognition. Pickets. Real Civil Rights pickets. Perhaps, inside, a sit-in was in process. Here it was at last, after all the endless, airless years in the Irish Channel back in Savannah, drowned in the twin shadows of the sleeping Creole South and the Mother Church.

Here was Life.

Caught in traffic--a significant, intractable traffic jam, what a wonder--my father averted his eyes from the picketers as if they were naked, and, lifting them toward the alien heavens above him, saw the dancer in her cage. He jerked his foot off the clutch, and the Vista Cruiser stalled.

"Jesus, Joseph, and Mary," he squalled. "I'm turning around this minute and taking you home! Sodom and Gomorrah, this place is. You got no business in this place, darlin'; look at that hussy, her bare bottom hangin' out for all the world to see. Look at those spooks, wantin' to eat in a place that don't want them. And have we passed a single church in all this time? We have not, and likely the ones that are here are all Protestant. I told your mother, didn't I? Didn't I tell her? You come on back with me now, and go back to work for the insurance people, them that want you so bad. Didn't they say they'd let you run the company newspaper, if you'd stay?"

Behind us a horn blared, and then another.

"Pa, please," I said. "It's nothing to do with me. I don't think my office is anywhere near here. Hank said it's across from a museum. I don't see any museum around here; I bet this part of town is just for tourists. And Pa? I'll go to Mass every Sunday and Friday, too, if I have time. And after all, I'm staying in the Church home for girls. What on earth could happen to me at Our Lady?"

"We don't know anything about these Atlanta Catholics," my father said darkly, but he started the Oldsmobile and inched it forward, into the next block.

"Catholics are Catholics. You've seen one, you've seen us all," I said in relief. We were past the go-go dancer and the marching Negroes now.

"I heard some of them take that pill thing--"

"Of course they don't!" I said, honestly scandalized. "You're just talking now. You heard no such thing."

"Well, I wouldn't be surprised if I did hear it," he said, but my shock had reassured him. He looked at me out of the corner of one faded blue eye and winked, and I squeezed his arm. My father was in his late sixties then; I was the last child of six, spawn of his middle age, born after he had thought the five squat red sons who were his images would be his allotted issue, and he was a bitter caricature of the bandy-legged, brawling little man upon whose wide shoulders I had ridden when I was small. But his wink could still make me smile, still summon a shaving of the old adoration that his corrosive age and his endless anger had all but smothered. Most of the time now I no longer loved my father, but here, closed in this warm car with the jeweled dark of my new city all around me, I could remember how I had.

"There's nothing for you to worry about," I said. "Aren't I Liam O'Donnell's daughter, then?"

The convent school where I had spent twelve millennial years back in Savannah, Saint Zita's--named after the patron saint of servants and those who must cross bridges; apt for my contentious lower-class neighborhood--was big on epiphanies. It was a favored mode of deliverance among the nuns in my day, perhaps because no one stuck in Corkie could conceive of any other means of escape. I had a speaking acquaintance with every significant epiphany suffered by every child of the Church from Adam on. But I had never been personally seized by one. It seemed somehow d‚class‚, bumbling and rural; my best friend Meg Conlon and I used to snicker whenever Sister Mary Gregory trotted out another for our edification.

"Zap! Another epiph has epiphed!" we would whisper to each other.

I had one then.

I sat in the warm darkness of my father's automobile, for the moment totally without contact with the world outside and newly without context of any sort, and saw that indeed I was Liam O'Donnell's daughter, wholly that, just that. Maureen Aisling O'Donnell, known as Smoky, partly for the sooty smudges of my eyelashes and brows and my ash-brown hair; smoke amid the pure red flame on the heads of my brothers. Twenty-six years on earth and all of them within the fourteen city blocks near the Savannah wharves that was Corkie, for County Cork, whence most of us who lived there had our provenance. Daughter of Maureen, sister of John, James, Patrick, Sean, and Terry. But unquestionably, particle and cell and blood and tenet, daughter of Liam O'Donnell.

It stopped my breath and paralyzed me with terror, and in the stillness my father laughed and pummeled my thigh, pleased and mollified, and said, "You are and no mistaking. See you remember it."

Downtown

- Mass Market Paperback: 512 pages

- Publisher: HarperTorch

- ISBN-10: 0061099686

- ISBN-13: 9780061099687