Excerpt

Excerpt

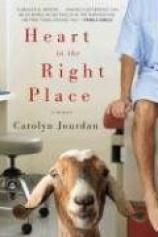

Heart in the Right Place

Prologue

“You’ll never see anything like this again,” Daddy said as he stooped to hold an x-ray between my face and the sunlight streaming in through his office window. He pointed to a shadowy gray blob near the center of a small rib cage.

“See?” he said. “This little girl’s heart’s on the wrong side. It’s on the right.”

I stared at the film, trying to appreciate what I was seeing. The silhouette of a little skeleton surrounded by vague swirls of silver mists and fogs looked okay to me, but I was only ten years old and trusted Daddy, a family doctor, to know which way the picture, and the heart, should go.

When I didn’t say anything, Daddy said, “You could go a whole lifetime without ever seeing this even once, because it’s so rare.”

I wasn’t sure, but I suspected this would be a good thing not to ever get to see again, because even though Daddy hadn’t said so, I got the distinct impression that this was a very bad thing for the little girl. I touched my own chest as I struggled to understand what the backwards configuration meant. But all I could think to say was, “How does she say the Pledge?”

For days I wrestled with the girl’s problem by asking Daddy variations of the same question, “What does she do when they play ‘The Star Spangled Banner’?... Where does she cross and hope to die?” I couldn’t get over it. Left was right and right was wrong. What did it mean?

Thirty years later, the image still haunted me.

What point was God trying to make with the little girl’s life?

He’d been more merciful with me. Despite my early fears that my destiny was to spend my entire life as an utterly powerless witness to one medical disaster after another, I’d eventually grown up and landed a good job in a city far from the mountains of East Tennessee, neatly sidestepping my role as spectator to any more catastrophes. Or so I’d thought.

Fall

One

As I unlocked the front door of the office I could hear the phone ringing. I hurried inside and stretched across the reception desk to answer it.

“Dr. Jourdan’s office,” I said, out of breath.

“Do y’all wash out feet?” a woman shouted.

I considered her question. Although I was accustomed to the local dialect and even to garbled medical terminology, I had no idea what she meant. I said, “Excuse me?” and quickly moved the earpiece a safe distance away from my head before she had time to respond.

“Wash out feet! Do y’all wash out feet?” she screamed.

“I... I don’t know.” I sent up a silent prayer that we did not.

“Well she needs her foot washed out! How much do y’all charge for that?”

If I was unsure if we even did such a thing, how could I know how much it would cost? “I don’t know,” I said.

In the ensuing silence I managed to add, “I’d ask the doctor, but he’s not here yet. I’ll find out when he comes in and call you back and tell you what he says. Okay?”

I fumbled through the piles of paper on Momma’s desk until I located a pencil and a blank scrap of notepaper, jotted down the woman’s name and number, and then hung up. I stared at the phone warily. Working as a temp for Daddy might be a little harder than I’d anticipated.

I hurried around to the other side of the reception desk in an attempt to put a bit of Formica between myself and the medical world. But before I’d even gotten seated atop the wooden stool that was the main feature of my new domain, I heard the front door open and then the unmistakable sound of elderly ladies, their voices worn out from too many years of use. One squeaked like a rusty hinge and the other crackled in an unpredictable jumble of soft and then suddenly loud sounds, like a radio with bad reception. The ladies were advising and encouraging each other in an effort to negotiate a small step at the front door. I turned and saw that it was the Hankins sisters, Herma and Helma, and their friend who lived with them, Miss Viola Burkhart.

I’d known them all my life. They were in their nineties. The Hankins sisters had never been married. Miss Viola was a widow who had come to live with them after her husband died. She was ninety-eight, weighed about seventy pounds, and had an advanced case of what the sisters called “old-timers.” Somewhere along the way she’d lost the ability or inclination to speak and now she wore a perpetual vacant smile.

Helma was ninety-five and also weighed less than 100 pounds.

She was extremely stooped, bent almost double from osteoporosis, and her eyesight wasn’t good. Herma was the baby at ninety-one and probably weighed more than both the other ladies combined. She was still sturdy but deaf as a post. So there was one who could hear and see, but not think or talk; one who could think, hear, and talk, but not see; and one who could think, see, and talk, but not hear.

The ladies were inseparable. Helma did the cooking and talking on the phone and Herma did the heavy work and the driving. Both of them took care of Viola.

Helma wore a faded green polyester leisure suit with an oddly intriguing assortment of safety pins arrayed along the edge of one lapel, while Herma had on baggy sweatpants and a misshapen sweater. Miss Viola was wearing a demure flowered dress. All three ladies wore shiny brown Naugahyde coats that had been fashionable in the sixties.

When they moved, they shuffled along together, holding onto each other for support and navigational assistance. They made their way carefully to the reception desk and Helma said that it was Miss Viola who needed to see the doctor today. Herma said, “Hey there, girl,” and smiled. “We was sorry to hear about your ma. How’s she doing?”

“Pretty good. She’ll be back Monday.”

Herma looked at me in confusion. “I thought she had a heart attack.”

“She did.”

“Ain’t she in the hospital?”

“Yeah, but she told me she’d be out by Monday.”

I was relieved when Herma decided to leave it at that. The story sounded a little thin, even to me, but I desperately needed to believe it.

Then, without even a hint of foreboding, I made my first executive decision in the health care arena. “You ladies can come right on back to the examining room,” I said. I figured it would be easier to get all of them up and down just once instead of twice;

and waiting in the back would protect them from exposure to whatever germs the other patients might bring in. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

As I helped them through the door that divided the waiting room from the rest of the office I said to Helma, “You ladies are lucky to have each other.”

She smiled. “Oh yeah, we got enough spare parts between the three of us to make one whole person!”

I took them back to Room 3 because it was the only room with enough places for all of them to sit down. Room 3 was used for surgery and contained Daddy’s pride and joy --- the hydraulic surgical table.

Thirty-five years ago, when he couldn’t really afford it, Daddy had bought the special motorized table that would raise and lower, so he could lift patients to a comfortable height while doing surgery. Even now the table still occupied a special place in his heart, like his Leitz microscope. No one was allowed to touch either piece of equipment but him.

The table was controlled by four pedals that lay flat on the floor. The entire table could be either raised or lowered, or it could be tilted by raising or lowering either the head or foot.

I seated Miss Viola in the middle of the table and told the ladies that the doctor would be in in a few minutes. Then I returned to my post at the reception desk. While I waited, I retrieved my phone messages from voice mail in Washington, D.C. My boss, Senator Hayworth, was conducting a series of hearings on corruption in the nuclear power industry, and I expected most of the calls would be related to that.

There were eleven messages. I sorted them with respect to time zone and then numbered them to indicate the order in which they should be returned. First came the calls to people on eastern time: government affairs representatives for the University of Tennessee and Tennessee Valley Authority. The call to a huge nuclear power conglomerate in Chicago could be made after 10:00, to a colleague in Sedona an hour after that, and then after noon I could reach the Los Angeles offices of the lobbyists for the electric power industry. Tokyo Power Company would come last, after 8:00 tonight. No problem.

As I dialed the Director of Federal Relations for the University of Tennessee, Daddy came in carrying a cardboard tray with a Styrofoam cup of coffee and a McDonald’s bag. He set his breakfast on the counter and I told him about the ladies waiting in Room 3. He nodded, fished his sausage biscuit out of the bag, and began to unwrap it.

Then he looked at me with his head tilted. “What’s that sound?” he said.

“I don’t hear anything,” I said, trying to stay focused on the opening pleasantries of my phone conversation.

He laid his biscuit down next to his cup of coffee and walked down the hall toward the back. I heard him pause at the doorway of Room 3 and say, “Good morn ---” Then he shouted, “What the hell’s going on in here?”

“Gotta go,” I said, hanging up on the Director while she was talking. Then I bolted for the back.

Things were not the way I’d left them. The surgical table’s motor, normally a low-pitched, almost inaudible hum, had changed to an angry whine. The head of the table was tilted as high as it would go, over five feet in the air, and the foot was down, almost touching the floor. Miss Viola had slid into a little wad at the lower end. Herma and Helma were frantically struggling to keep her from falling onto the floor, but she was oblivious. She smiled serenely as Herma tugged on her arms and Helma hoisted her ankles.

I couldn’t understand why this was happening. It sounded like someone was standing on a cat’s tail. I looked down reflexively and noticed that Herma had somehow come to be standing on the floor pedal that raised the head end of the table. She clearly didn’t realize what she was doing, nor could she hear the table motor running.

Daddy shouted a one-word accusation, “Carolyn!” and leapt forward to snatch up Miss Viola. As she slipped off the end of the table, her dress peeled up over her head. He tried to set her on her feet, but she was so dizzy she couldn’t stand by herself. He told Herma to get her foot off the control pedal, but she couldn’t hear well enough to understand what he was saying.

He made a series of shuffling hops sideways, crushing Viola tightly against his side, and startled Herma by lifting her bodily off the pedal with his other arm. He held one lady under each arm while he stomped on the “Head Down” control.

All of this confusion and manhandling sent the sisters into a tizzy. And Daddy was incensed that anyone would dare touch the controls of his table, much less put such a terrible strain on it.

“What’d you do that for?” Daddy shouted at Herma in a voice so thunderous that she finally heard him.

“Do what? I didn’t do anything. Your table there is broken.”

“It better not be!” he said.

When the table was level again, he set Miss Viola back down in the center and flipped her dress down over her legs. She seemed neither startled nor embarrassed. In fact, she seemed to have missed the whole ordeal.

Under the circumstances Daddy decided to go ahead and tend to Miss Viola’s medical problems before normal office hours. He patiently listened to the health concerns of all three ladies and wrote prescriptions all round.

As the ladies drove away, Daddy went back to his sausage biscuit. He stared at me while he chewed and then said, “Don’t ever do that again.”

“Don’t do what?” I said. “Don’t leave any old ladies alone with any of your stuff?”

“Just don’t do it again,” he snapped and took his biscuit into the back to eat it in peace.

We were both under a lot of stress.

A few minutes later, Alma, Daddy’s nurse, confided that during her entire twelve years with the doctor she’d never heard him shout like that before.

“Well, just stick with me,” I said. “I’ve been with him for forty years and I’ve been hearing it the whole time.”

Daddy was fantastic at handling medical emergencies. He was unbelievably cool under pressure if, say, someone had cut off their arm or leg with a chain saw. But he simply wasn’t equipped to handle the kind of emergencies that seemed to crop up whenever I was around. He could cope beautifully with every kind of chaos, except the kind I created. And right now he was stuck. He couldn’t work with me, and he couldn’t work without me.

I felt for him. It was a good thing I was only going to be subbing in this job for two days. If I stayed a week, he’d end up sharing a room with Momma in the cardiac ward.

Heart in the Right Place

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Algonquin Books

- ISBN-10: 1565126130

- ISBN-13: 9781565126138