Excerpt

Excerpt

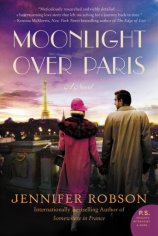

Moonlight Over Paris

Prologue

Belgravia, London

December, 1923

Helena had heard, or perhaps she had read somewhere, that people on the point of death were insensible to pain. En- veloped in a gentle cloud of perfect tranquility, all earthly

cares at an end, they simply floated into oblivion.

It was rubbish, of course, for she was in agony. Pain seized at her throat and ears, so fierce and corrosive that she could sleep only when they drugged her, and even then it chased her from one nightmare to the next. She hurt from her scalp to her fingernails to the soles of her feet, and despite that very real reminder of her state among the living, she knew the truth, too—she was dying.

She had heard the doctor say so not a half hour earlier. He had told her parents there was no hope, she had heard her mother weeping, and she had wished, then, that she had lived when she’d had the chance. There were so many things she ought to have done, and would never have the chance to do, not now. Not with the doctor so certain and her parents so broken.

She slept, waking only when day had faded to night and her room was empty of everyone apart from one woman, a stranger, dozing in the corner. A nurse, she supposed.

She felt a little cooler, and the ache in her throat was a trifle less pronounced. A drink of water would be nice, but if she called out the nurse would insist on painting her throat with that bitter substance again. Something-something of silver. It ought to have been cool, for silver put her in mind of moon- lit nights and alpine lakes, but instead it burned horribly and made her choke.

So she lay still through the slow, beckoning hours before dawn, and presently it occurred to her that doctors were some- times wrong. People did rise from their sickbeds and astonish their families from time to time, and there was a small chance—admittedly a vanishingly small one—that she might be among the few to do so. She had always been a healthy girl, never much given to illness, and had recovered from the Spanish flu in record time only a few years earlier. Perhaps she would survive after all.

And if she did? W hat next? Another twenty years of trailing dutifully after her mother, all the while knowing what people were whispering behind their hands?

Cast aside at the eleventh hour, all so he might marry the governess. Such a tragedy for her. And her poor parents—the shame of it all. The shame. . .

For five years she’d been engaged to a man who scarcely no- ticed her existence, treating her as an afterthought in his life. And then, after their engagement had been called off, nearly everyone she’d known in London had erased her from their lives, choosing to believe she had been at fault. No one, apart from her parents and sisters, had defended her.

Invitations had ceased. Callers had stopped coming by.

Doors had been shut in her face. Lord Cumberland had been a war hero, awarded a chestful of medals for his valor, and she had, it was assumed, heartlessly cast him aside. No matter that she had released him from their engagement only after he begged her to do so. After he confessed that he had never loved her, and had agreed to marry her only because of pres- sure from his family.

Looking back, it seemed almost impossible that she had stood meekly by and allowed people to treat her so shame- fully. W hy hadn’t she defended herself with greater vigor? W hy hadn’t she simply gone abroad? It seemed obvious now, but it hadn’t once occurred to her then.

It was high time she moved past all of that. She would go somewhere . . . she wasn’t sure where, but it would be some- where else, somewhere new where no one cared about her dis- appointments and failures. And she would . . . she wasn’t sure what she would do, not yet.

But she was certain of one thing. If she survived, she would live.

Chapter 1

Belgravia, London

March, 1924

Helena tapped her forefinger into the pot of rouge and rubbed a dot of color into the apple of one cheek and then the other, just as her sister Amalia had instructed. She was to start

with the slightest wash of color, and build from there. Rather as she would do when painting, though this was the first time she’d ever applied pigment to her face.

She pulled back from her dressing table mirror and surveyed her reflection with an unflinching eye. The rouge had helped to reduce the pallor of her complexion, a little, though nothing could be done about the thinness of her face, nor the dark circles that ringed her eyes. Worst of all was her hair, which the doctor had ordered be shorn when her fever refused to break. After four months it had scarcely grown at all, and was only just beginning to curl around her ears and nape. It was rather pleasant to be free of the bother of arranging it, at least until it grew back, but she could have done without the sympathetic sighs and half-hidden stares. On the other hand, women everywhere were shingling their hair these days; this was simply a more radical version.

It wouldn’t do to remind her parents of her illness too force- fully, however, so she wrapped a long scarf around her head, tied it at her nape, and let the ends trail down her back. The effect was rather bohemian, but fetching all the same, and the bright blue of the patterned silk, a gift from her aunt Agnes, helped to brighten her eyes.

The letter from Agnes had arrived a month before, drop- ping into her lap like a firecracker.

51, quai de Bourbon

Paris, France

12 February 1924

My dearest Helena,

Words cannot express my joy when I received your letter of Tues- day last and was able to read, in your very own words, that you have recovered from your illness and are nearly restored to health. Your account was so terribly moving—I have read it through a dozen times already and it never fails to bring tears to my eyes.

I must commend you for your resolution to effect a wholesale change in your life. The past five years have been so very difficult for you, and you have borne your sorrows admirably—but it is long past time that you thought of your future, and I think any course of action that takes you away from London is a sound one.

I have two suggestions that I hope you will consider. First, I would be very happy if you would come to stay with me in France. You said in your letter that you wished to LIVE—I so love your use of capital letters here—and where better than France for such an endeavor?

Second—and let me emphasize that this is a suggestion and not an edict—if you do come to stay I think it best if you find some way to occupy your days. I live quietly, and I worry that you would quickly find my company boring—but if you have something to do you will be much happier for it. Given your interest in art, and your undeniable talent in that regard, I think you ought to consider a term of study at one of the private academies in Paris. To that end I have enclosed the brochures for three such schools, and it is my fervent hope that you consider enrolling in one of them for the autumn term.

I leave for Antibes at the end of this week—write to me there, no matter what you decide.

With affectionate good wishes

Auntie A

Folding the letter away, Helena looked in the mirror one last time. It was time.

Her parents weren’t expecting her for luncheon; had she mentioned it, during her mother’s visit that morning, she’d have been subjected to a visit from Dr. Banks, whom she had grown to detest, and then guided down the stairs by two maids at the least. Before she could set her plans in motion, she had to show Mama and Papa that she was fit to rejoin the world, and that began with dressing herself and walking down the stairs without anyone hovering at her elbow.

It was only the third or fourth time she’d ventured beyond her bedroom door since the fever had broken and her recovery had begun, and despite herself she felt rather cowed by the number of stairs she had to descend in order to reach the dining room on the floor below. But she had done it before and would manage it again. One step, and another, and finally she was crossing the hall and smiling at Farrow the footman, who looked as if he might faint when he realized she was alone.

“Don’t worry,” she whispered as he opened the door to the dining room. “If they fuss I’ll tell them you helped me.”

The vast expanse of the dining table was empty, apart from a trio of silver epergnes that marked its central leaves, for her parents had chosen to sit at a small table in front of the French doors overlooking the garden. Helena cleared her throat, not wishing to startle them, and braced herself as their expres- sions of delight turned to concern.

“Helena, my dear—what are you doing out of bed? When I saw you this morning—”

“I told you I felt quite well, Mama, and I feel perfectly well now. May I join you for luncheon?”

“Of course, of course,” her father chimed in. “Take my place,” he offered, pushing back in his chair, but Helena stopped him with a hand on his shoulder.

“No need, Papa; look—here is Jamieson with another chair, and Farrow has everything else I need.”

In moments she was seated, a hot brick under her feet, a rug on her lap, and a shawl about her shoulders, her parents deaf to her insistence that she was perfectly warm. Too warm, in fact, and though it was heavenly to feel the sun on her face she began to hope that a passing cloud might offer some respite.

“Are you quite comfortable? Shall I ring for some broth? And some blancmange to follow?”

“Oh, goodness no—I’ll have the same as you. Dr. Banks did say I might resume a normal diet.”

“I know he did, but you must be cautious,” her mother fussed. “Any sudden change—”

“I hardly think a few mouthfuls of trout and watercress will do me in.”

“Let the girl eat in peace, Louisa. She’s been cooped up in this house for far too long,” her father insisted. “Past time she returned to the land of the living.”

They ate in silence, companionably so, and in no time at all Helena had finished everything on her plate. She cleared her throat and waited until she was sure she had her parents’ full attention.

“I have something to tell you. The both of you.”

Her mother set down her fork and knife, her face suddenly pale, and folded her hands in her lap. “W hat is it, my dear?”

“I’ve been thinking about what I ought to do. I’m feeling ever so much better, you see, and I should like so much to go somewhere warm, perhaps—”

“Splendid notion,” said her father. “I’ve always been partial to Biarritz at this time of year.”

“It is lovely, I agree, but I’ve decided to go to the Côte d’Azur. To stay with . . . well, to stay with Aunt Agnes.”

“Ah. Agnes.”

“She is your sister, Papa, and she is very fond of me. And the weather in the south of France will do me good.”

“Of course it will,” her mother agreed, “and you know how we adore dear Agnes. But she lives a . . . well, a rather uncon- ventional life. You really ought to stay with a steadier sort of person. Maudie Anstruther-MacPhail, perhaps? She’s wintering in Nice this year.”

“I scarcely know the woman, and Aunt Agnes would be awfully hurt if she found out.”

“You’re still so fragile. Remember Dr. Banks’s warning—any sudden upset or disturbance—”

“I’m a woman, not a piece of spun sugar, and I am perfectly capable of making sensible decisions. You know I am. Even if Aunt Agnes got it into her head to go off on one of her adventures, I would simply stay put. She has plenty of servants. I wouldn’t be left on my own.”

“And would you promise to be perfectly careful of your health?”

“Yes, Mama.”

“John? W hat do you think of this?”

“Agnes is a good sort. A lways has been. Shame about that husband of hers, of course, but she rallied. She always does.”

“A summer in the sun will do you good, I suppose,” her mother mused.

“Yes. Well, the thing is . . . I’m staying for longer than that. For a year, in fact.”

“For a year? Why so terribly long?”

“I have enrolled in art school, and the term runs from Sep- tember to April.”

Silence descended upon the table, as cold and numbing as November rain.

Her mother was the first to recover from her shock. “Art school? I don’t know about that. Filled to the brim with foreigners, and the sort of art that is fashionable these days—”

“Degenerate rot,” her father finished. “Makes no sense. W hy bother with a painting that doesn’t look like anything? If I buy a portrait of my wife, I want it to look like my wife. Not a hodgepodge of shapes. W ho has a head shaped like a box, I ask you? No one!”

“Cubism is merely one approach among many, and the school I have in mind is far more traditional,” Helena insisted, mentally crossing her fingers. “Maître Czerny isn’t interested in what is fashionable. His focus is on technique.”

Her mother wrinkled her nose. “ ‘Chair-knee’? What sort of name is that?”

“I believe it’s Czech, originally. But he is a Frenchman. And he would be willing to take me on—”

“What? You’ve been corresponding with this man?”

“Only regarding his school, Mama.”

“What of the other students? Foreigners as well?”

“I don’t know. Most likely most of them will be French. Possibly there will be some Americans, too.”

“Good heavens,” her mother said. She had begun to worry at the lace on her cuff, which was never a good sign. “I really don’t know if we can agree to this.”

It was time to dig in her heels. “Mama, I am twenty-eight years old, and I have money of my own. I have the greatest respect for you both, but you must remember that I have the legal right to go and do as I please.”

“But Helena, darling—”

Her heart began to pound, for she’d never stood up to her parents in such a way before, and it went against her nature to do so now. But she had to hold her ground. Before her resolve crumbled, she needed to step away.

“If you’ll excuse me, I think it’s time I return to my room. If you wish to speak with me about my plans I will be very happy to do so.”

Back in her bedchamber, Helena took up her notebook and pencils, and looked around for something she might draw. Settling on the window seat, she began to sketch the wrens that came to perch on the sill each afternoon. They were sweet little creatures, tame enough to alight on her outstretched fin- gers, and cheery despite the threatening rain. It was spring, after all; they had survived the winter, and seemed to know that blue skies lay ahead. If only she could be as certain.

She had no education to speak of, nor was she beautiful or witty or elegant. But something came alive in her when she picked up a pencil or brush. She had the makings of an artist in her, she was certain of it, and she was determined to keep the promise she’d made to herself last December, in those bleak, lonely hours when death had crept so close. Her parents wouldn’t stop her, she knew, but it would be so much easier, and pleasanter, if they were to support her decision.

She meant to close her eyes for just a moment, but when she woke the sun had sunk beneath the garden wall and her mother was at her side, a cool hand smoothing her brow.

“You shouldn’t have fallen asleep there,” Lady Halifax fret- ted. “You might have caught a chill.”

Helena crossed the room and settled in one of the easy chairs drawn close to the fire. “I’m fine. Not cold at all.”

Her mother perched at the edge of the other chair, her stays creaking a little, and smiled rather wanly at Helena. “Papa and I have been talking. As you said earlier, you have always been such a good girl, and we do trust you. W hile we have our reservations about this, ah, this academy you wish to attend, we have decided to support your decision to go to France for a year.”

“Thank you, Mama. I really am very grateful.”

“I know you think I worry too much, but I can’t help myself. I know how you have suffered, how people have treated you since your break with Lord Cumberland. I know how lonely you’ve been—”

“I’ve always had you and my sisters, Mama. It hasn’t been that bad.”

“It has. And it’s so unfair. Just look at Lord Cumberland. He’s been happily married all this time, has children of his own, and no one says a thing to him.”

“It’s in the past, Mama. You mustn’t dwell on it.”

“How can I not? You’re almost thirty. Before long it will be too late for children, and then what decent man will have you? Please be sensible.”

“I have always been sensible, and that is why I have no interest in marriage with some stranger who is indifferent to me. I was lucky to escape such a fate with Edward.”

Her mother pulled a handkerchief from her sleeve and dabbed at her eyes. “How can you say you were lucky, when he all but ruined your life? If only you knew how it weighs upon me. What if something were to happen to your father? You know we cannot depend on your brother, for that wretched wife of his won’t wait five minutes before tossing us all out of the house. I don’t much care what happens to me, but you, my darling—what will become of you?”

Helena took her mother’s hands and pressed them reassur-ingly between hers. “Listen to me: if the worst were to happen, and David’s vile wife were to throw us out on our ears, we would take my bequest from Grandmama, buy a little house, and live quite comfortably together. But that is not going to happen, not least because Papa is as healthy as an ox, and likely to remain so for many years.” She smiled at her mother, willing her to believe, and received a feeble nod in response.

“I am going to France to live with Auntie A for a year, and to try to become an artist, and when the year is done I will think seri- ously about what I must do next. But I need my year first. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” her mother offered, her voice wobbly with tears, though she dried her eyes quickly enough. “Now, my dear: be honest with me. Are you well enough to travel?”

“Not quite yet,” Helena answered truthfully. “Perhaps in a fortnight?”

“Very well. Shall we see how you are at the end of next week? If you feel improved, I’ll have Papa’s secretary book passage for you to Paris.”

“Aunt Agnes is already at her house in Antibes, though. Wouldn’t it be better if I took the Blue Train from Calais?”

“That does make sense. Shall I have a tray sent up with your supper?”

“Yes, please.”

“Tomorrow we’ll go for a nice walk together. And we must see about getting you some pretty things for the seaside.”

“Thank you, Mama. For everything, I mean.”

As soon as the door closed behind her mother, Helena erupted from her chair and jumped up and down, taking great skips around the room, though it made her breathless and so unsteady on her feet that she had to sit again almost right away.

She had done it.

She would have her year in France, a year away from the whispers, stares, and malicious half-heard gossip that had blighted nearly every moment of the past five years. She would . . . her mind reeled at the possibilities. She would eat pastries and drink wine and wear short skirts and rouge, and she would sit in the sun and burn her nose, and not care what anyone thought of her.

Best of all, she would go to school and meet people who knew nothing of her past, and to them she would simply be Helena Parr, an artist like themselves.

Helena Parr. Artist. Merely thinking the words filled her with delight—and it reminded her of one task that simply couldn’t wait.

Returning to her desk, she took out a sheet of notepaper and began to write.

45, Wilton Crescent

London, SW1

England

16 March 1924

Dear Maître Czerny,

Further to my earlier inquiry, I should like to reserve a place at your school for the September 1924 session for intermediate stu- dents. I shall send a bank draft for the required deposit under sepa- rate cover.

Yours faithfully, Miss Helena Parr

Moonlight Over Paris

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0062389823

- ISBN-13: 9780062389824