Excerpt

Excerpt

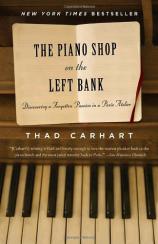

The Piano Shop on the Left Bank: Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier

Chapter 1

Luc

Along a narrow street in the paris neighborhood where i live sits a little store front with a simple sign stenciled on the window: "Desforges Pianos: outillage, fournitures." On a small, red felt-covered shelf in the window are displayed the tools and instruments of piano repair: tightening wrenches, tuning pins, piano wire, several swatches of felt, and various small pieces of hardware from the innards of a piano. Behind the shelf the interior of the shop is hidden by a curtain of heavy white gauze. The entire façade has a sleepy, nineteenth-century charm about it, the window frame and the narrow door painted a dark green.

Not so many years ago, when our children were in kindergarten, this shop lay along their route to school, and I passed it on foot several times on the days when it was my turn to take them to school and to pick them up. On the way to their classes in the morning there was never time to stop. The way back was another matter. After exchanging a few words with other parents, I would often take an extra ten minutes to retrace my steps, savoring the sense of promise and early morning calm that at this hour envelops Paris.

The quiet street was still out of the way and narrow enough to be paved with the cobblestones that on larger avenues in the city have been covered with asphalt. In the early morning a fresh stream of water invariably ran high in the gutters, the daily tide set forth by the street sweepers who, rain or shine, open special valves set into the curb and then channel the flow of jetsam with rolled-up scraps of carpet as they swish it along with green plastic brooms. The smell from la boulangerie du coin, the local bakery, always greeted me as I turned the corner, the essence of freshly baked bread never failing to fill me with desire and expectation. I would buy a baguette for lunch and, if I could spare ten minutes before getting to work, treat myself to a second cup of coffee at the café across the street from the piano shop.

In these moments, stopping in front of the strange little storefront, I would consider the assortment of objects haphazardly displayed there. Something seemed out of place about this specialty store in our quiet quartier, far from the conservatories or concert halls and their related music stores that sprinkle a select few neighborhoods. Was it possible that an entire business was maintained selling piano parts and repair tools? Often a small truck was pulled up at the curb with pianos being loaded or unloaded and trundled into the shop on a handcart. Did pianos need to be brought to the shop to be repaired? Elsewhere I had always known repairs to be done on site; the bother and expense of moving pianos was prohibitive, to say nothing of the problem of storing them.

Once I saw it as a riddle, it filled the few minutes left to me on those quiet mornings when I would walk past the shop, alone and wondering. After all, this was but one more highly specialized store in a city known for its specialties and refinements. Surely there were enough pianos in Paris to sustain a trade in their parts. But still my doubt edged into curiosity; I saw myself opening the door to the shop and finding something new and unexpected each time, like a band of smugglers or an eccentric music school. And then I decided to find out for myself.

I had avoided going into the shop for many weeks for the simple reason that I did not have a piano. What pretext could I have in a piano furnisher's when I didn't even own the instrument they repaired? Should I tell them of my lifelong love of pianos, of how I hoped to play again after many vagabond years when owning a piano was as impractical as keeping a large dog or a collection of orchids? That's where I saw my opening: more settled now, I had been toying with the idea of buying a piano. What better source for suggestions as to where I might find a good used instrument than this dusty little neighborhood parts store? It was at least a plausible reason for knocking.

And so I found myself in front of Desforges one sunny morning in late April, after dropping off the children down the street. I knocked and waited; finally I tried the old wooden handle and found that the latch was not secured. As I pushed the door inward it shook a small bell secured to the top of the jamb; a delicate chime rang out unevenly, breaking the silence as I swung the door closed behind me. Before me lay a long, narrow room, a counter running its length on one side, and along the facing wall a row of shelves laden with bolts of crimson and bone-white felt. Between the counter and the shelves a cramped aisle led back through the windowless dark to a small glass door; through it a suffused light shone dimly into the front of the shop. As the bell stopped ringing and I blinked to adjust my eyes, the door at the back opened narrowly and a man appeared, taking care to move sideways around the partly opened door so that the view to the back room was blocked. "Entrez! Entrez, Monsieur!" He greeted me loudly, as if he had been expecting my visit; he looked me up and down as he made his way slowly to the front of his shop. He was a squarely built older man, probably in his sixties, with a broad forehead and a massive jaw that was fixed in a wide grin; the eyes, however, did not correspond to the mouth. His regard was intense, curious, and wholly without emotion. I realized that the smile was no more than his face in repose, a somewhat disquieting rictus that spoke of neither joy nor social convention. Over his white shirt and tie he was wearing a long-sleeved black smock that hung loosely to his knees and gave him a formal yet almost jaunty appearance, like an undertaker on vacation. This was clearly the chef d'atelier, wearing a more sober version of the deep-blue cotton smocks that are the staple of craftsmen and manual laborers throughout the country.

We shook hands, the obligatory prelude to any dealings with another human being in France, and he asked how he could be of help. I explained that I was looking to buy a used piano and wondered if he ever came across such things. A slight wrinkling of his brow suggested that my question surprised him; the smile never varied, but I thought I detected a glint in his eyes. No, he was sorry, it was not as common as one might think; of course, once in a great while there was something, and if I wanted to check back no one could say that with a stroke of luck a client might not have a used piano for sale. Both disappointed and puzzled, I couldn't think of how to keep the conversation going. I thanked him for his consideration and turned to leave, casting a last glance at the ceiling-high shelves behind the counter stuffed with wooden dowels, wrenches, and coils of wire. As I pulled the door behind me he turned and headed toward the back room once again.

I returned two, perhaps three times in the next month and always the reaction was the same: a look of perplexity that I might consider his business a source of used pianos, followed by murmured assurances that if ever anything were to present itself he would be delighted to let me know. I was familiar enough with the banality of formal closure in French rhetoric to recognize this for what it was: the brush-off. Still I persisted, stopping by every few weeks out of sheer doggedness and curiosity. I was just about to give up hope when a development changed the equation, however slightly. On this occasion, as before, my entry set off the little bell and the door at the back of the shop opened a few moments later. But instead of the black-smocked patron there appeared a younger man—in his late thirties, I guessed—wearing jeans and a sweat-soaked T-shirt. His face was open and smiling, and ringed by a slightly scruffy beard that gave him the look of a French architect. More surprising than the new face was the fact that he left open the door to the back room; as he walked toward me I peered over his shoulder for a glimpse of what had so long intrigued me.

The room beyond was quite long and wider than the shop, and it was swimming in light pouring down from a glass roof. It had the peculiar but magical air of being larger on the inside than the outside. This was one of the classic nineteenth-century workshops that are still to be found throughout Paris behind even the most bourgeois façades of carved stone. Very often the backs of buildings were extended to cover part of the inner courtyard and the space roofed over with panels of glass, like a giant greenhouse. I took this in at a glance and then, in the few seconds left to me as he made his way along the counter, I realized that the entire atelier was covered with pianos and their parts. Uprights, spinets, grands of all sizes: a mass of cabinetry in various tones presented itself in a confusion of lacquered black, mahogany, and rich blond marquetry.

The man gestured with his two dirty hands to excuse himself and then, as is the French custom when hands are wet or grimy, he offered his right forearm for me to shake. I grasped his arm awkwardly as he moved it up and down in a parody of a shake. I explained that I had stopped in before and was looking for a good used piano. His face broke out in a smile of what seemed like recognition. "So you're the American whose children go to the school around the corner."

I accepted this description equably and asked how he had known. It didn't surprise me that in the close-knit neighborhood he was aware of a foreigner who daily walked down his street even though we had never met.

Excerpted from The Piano Shop on the Left Bank © Copyright 2002 by Thad Carhart. Reprinted with permission by Random House. All rights reserved.

The Piano Shop on the Left Bank: Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Random House Trade Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0375758623

- ISBN-13: 9780375758621