Interview: May 3, 2012

In the midst of reading Alison Bechdel’s newest memoir, ARE YOU MY MOTHER?, an amazing thing happens: You begin to realize how truly universal this story is, regardless of the type of relationship you have with your own mother. The analytical search for identity forms and shapes us, and the older we get, the more we want to trace our foundations and understand the nature vs. nurture conflict that went us within our own beings as we developed.

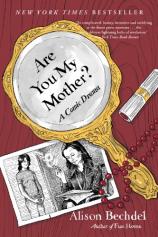

Bechdel won an Eisner Award for FUN HOME, her memoir regarding her father’s closeted homosexuality and suicide, and the personal aftermath she faced from both. The book was named as a best book of the year by several publications, and she is also best known for her long-running comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. In her latest, she tries to unlock the secrets of her relationship with her mother by delving into why her mother stopped hugging her at a very young age, how her mother encouraged and discouraged the work Bechdel does, and how all of it impacted her relationships with friends, lovers and therapists throughout her life.

The story is further examined through the lens of the writings of psychologist Donald Winnicott, who becomes a sort of father figure and reassuring presence to Bechdel. The need for parental approval and closeness fuels much of Bechdel’s work. Here is what she had to say about writing the book, reliving the deeply personal stories, and finding out not only who her mother was but also who she herself is.

Question: Once I finished reading ARE YOU MY MOTHER?, I immediately wanted to read it again, just to figure out how to absorb it all. To me, it’s interesting and intriguing that your shockingly personal story can also be universal. It shows how we’re all trying to understand our mothers and our relationships with them.

Alison Bechdel: I’m very happy to hear you say that, because I’m not really sure yet. I feel like my own story is so idiosyncratic and I do go into such minute detail about it that I hope other people can relate to it. I’m very glad to hear that you did.

Q: Much of the book is about your struggle to actually write this book. And you mention that you were working on it, in some ways, even before FUN HOME. Does it feel like a relief to finally let it go after all that, or is it sad?

AB: I think I’m still letting go of it. I feel like somehow the writing and drawing of the book isn’t the whole process; that now begins the process of talking about it in public. For FUN HOME, that public reaction was definitely a part of my whole creative arc with the book. I didn’t really understand it until it was out in the world, and I feel like that’s probably going to happen again with ARE YOU MY MOTHER?

Q: I know it was a very different work, but did you feel the same way about Dykes to Watch Out For?

AB: No, that worked out really different. In my comic strip, I wasn’t venturing into the unknown in quite the same way that I have been in these memoirs. [Laughs] I had a topic and different plot lines I had to resolve. It was all kind of given. Within that, I would do a little inventing and didn’t quite know what was going to happen, but it wasn’t unknown in the same way that I feel like I’m doing now.

Q: I was originally thinking of asking a reviewer, a male reviewer, to review ARE YOU MY MOTHER? for this site. I knew he had really loved FUN HOME, but he told me I should give it to a female reviewer. I’m curious how you feel about that.

AB: That’s what I’m afraid of, that men are not going to be interested in reading about a mother story. I feel kind of worried about it, so it’s interesting to hear that that guy had that response. I don’t really know what to say to that. It wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world if men just didn’t want to read it, but everyone always wants their book to be read broadly…so I just don’t know what’s going to happen.

Q: I should clarify that this guy can’t wait to read the book. It’s not that he’s not interested in the topic. He just didn’t think a man would be as qualified to review it as a woman.

AB: Oh! Well, that’s ridiculous. [Laughs]

Q: In your dedication for the book, you mention that your mother always knew who she was. Through writing this book, do you now feel that you understand who she was? Or is?

AB: [Pause] I feel like I understand a little more than I did as a child and a young person. You know, I was really forcing myself to try and see her life from outside of my own perspective, which was a really useful exercise. Probably because she doesn’t really talk much about herself, I had to do a lot of speculating, a lot of just imagining, like extending myself imaginatively into her character. That’s a really useful exercise.

Q: I think my parents came from the same generation as yours, and had a similar reticence or held things back in the same way. They would feel that revealing too much about themselves would be self-indulgent or something.

AB: Oh, totally. Yeah. I could never ask my mother anything directly. God forbid.

Q: Are you still trying to get pieces of information out of her? Are you working on ways of conversing with her to get her to reveal things you want to know?

AB: No, because she can see through that. [Laughs] I don’t even try. She does reveal information when she feels like it, and only when I’m not prying for it. And you know, I feel like that’s always true. Our lives are just these mysteries. We find out little clues here and there along the way, but you never get all the information all at once. You don’t get it when you think you’re going to, or in the form you’re expecting. But gradually, you start putting it all together.

Q: How long ago did you finish working on the book?

AB: Not very long ago.

Q: So it’s still pretty raw and recent.

AB: Yeah, it’s pretty raw. [Laughs] In fact, I just got the physical book two days ago. For the first time, I held the actual bound book in my hand. I feel like I didn’t understand until that moment, really, or didn’t have a sense until that moment of the book as a whole thing. I’m not sure I really do now. There’s no way to replicate that bound quality, you know? I had a loose-leaf binder I had all my pages collected in, but somehow the actual book is a different matter. This is probably not unusual, but I always have a spasm of horror when I see anything hot off the press, because all I see are the mistakes. I immediately started spotting hundreds of things I wish I had fixed. I haven’t quite moved past that state yet.

Q: The color palette, with the red and the subdued tones, is interesting. What was the reasoning behind it?

AB: I wanted to use two colors, as I did with FUN HOME. That was just black with that green-silver print shading. But I did something different with the colors here. First of all, I couldn’t use the same color, and I couldn’t use any kind of green color, so I started to figure out what other kind of possibilities there were, since really there aren’t that many colors. It was like red was the only possibility, really. And I did something a little more complicated. I used that red as a spot color, and I used it in different opacities, like I had a lighter version on a darker version, but it’s still only one color. And then when it combines with the gray ink brush shading, it’s exciting to me because you can get this kind of wide range of tone variation only using black and red ink. That was fun for me.

Q: In your creative process, do you write out the script first and then draw the images?

AB: Yes, although I should specify that when I write, I write in a drawing program. So I’m not just sitting at the typewriter doing a word-processing document. I’m actually laying my pages out in panels and thinking visually in terms of what the images are going to be. I just don’t do the actual hands-on penciling at that point.

Q: In ARE YOU MY MOTHER?, you quote a lot from the works of psychologist Donald Winnicott. Did you do all of those passages by hand, or did you use a computer to do them?

AB: [Laughs] Insanely, I did all that lettering! The lettering for my writing I do digitally. But for some reason, all those passages that I quoted I did trace from the actual books.

Q: Wow, that’s amazing. That must have taken you a really long time.

AB: It took forever! It was insane. But somehow I felt like I had to do it. There was something about wanting to bring the quotations alive or wanting to replicate the experience of reading through my eyes, maybe. Somehow that had to come through my hand.

Q: Have you always felt this connection to Winnicott that gets explored so much in the book?

AB: I really didn’t know that much about him until I started researching the book. I had heard of him and had read a little bit about him before that, but it wasn’t until 2006, 2007 that I really started studying him. I can’t really remember when I decided Winnicott was going to be a big part of this book. I feel like my life has just been a blur since I started working on it. I can’t quite figure it out.

Q: Which is interesting, because one of the things I loved about the book is the jumbling of time throughout. It’s not linear; it’s almost stream of consciousness. I love that, because I think that’s the only way to tackle a subject like this.

AB: Yeah, keeping track of the chronology of the book was incredibly complicated, and inevitably I would find myself circling back, or spiraling back, into the present, into my present self telling the story of my past, and just getting very confused with what perspective I was speaking from at any given moment.

Q: There’s a line in the book that really moved me. It’s from a session you were having with your therapist Jocelyn. She says she likes you, and you write in the book, “I lived for weeks on her reply.”

AB: I’ve heard many people talk about that with their therapists. It’s just kind of amazing that we’re all such wretches. [Laughs] It’s how we function in the world.

Q: I hope this isn’t too personal a question, but since Winnicott and his work have such a big presence in the book, I was curious: Did you ever try a male therapist?

AB: I did not. No. When I was younger, I was in this lesbian community and it would never have occurred to me to see anyone but another lesbian. And then as I got older…my current therapist is not a lesbian. I started realizing that I had a couple other therapists who were lesbians and it just got too socially complicated, because the social network is so small that it got awkward. But it didn’t occur to me that I should see a man. It occurred to me that I had better see a heterosexual. [Laughs] The thing about Winnicott is he’s such a curiously androgynous character. He is a man, but he’s this very maternal man, even physically. It took me a long time, but I finally obtained a recording of his voice, and he has a very feminine voice; he even sounds like a woman when he’s speaking. People described him as fey, as too small. So that’s kind of interesting, too.

Q: You talk about FUN HOME a lot in the book, but you never actually mention it by name. Is there a reason for that?

AB: I guess I felt like I couldn’t be certain readers would know that book, so I just didn’t refer to it by name. I didn’t want to get too self-referential [laughs], which is such a silly thing to say because it’s such a self-involved book, but I sort of drew a limit there, I guess.

Q: What was the hardest part of the book for you to relive as you were writing and drawing it?

AB: It was definitely that whole childhood sex drawing thing, where my mother finds the dirty pictures I drew. That was excruciating. I can hardly even read it now. But the irony of it is, I finally showed the book to my mother and she said, “I have no memory of those dirty pictures.” My whole life I’ve been walking around in shame because of that, and she doesn’t even remember!

Q: Do you have more memoirs you plan on writing?

AB: Yes! Believe it or not, I still have more stories I want to tell after this, more nonfiction, as long as people are interested in reading them.