Interview: September 16, 2020

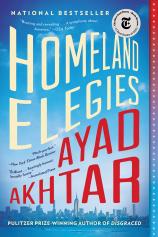

Ayad Akhtar is a novelist and playwright who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his play “Disgraced” and whose debut novel, AMERICAN DERVISH, was named a Kirkus Reviews Best Book of 2012. His highly anticipated second work of fiction, HOMELAND ELEGIES, is about an immigrant father and his son who search for belonging --- in post-Trump America, and with each other. In this interview, conducted by Bookreporter.com reviewer Harvey Freedenberg, Akhtar talks about one of the book’s most powerful scenes --- Ayad’s description of his experience in Manhattan on 9/11 --- and how he went about recreating the terrible sights and overwhelming emotions of that day; what he thinks it will take for those who harbor suspicions about Muslims to view them with less hostility; and the pivotal role that dreams play in the novel.

The Book Report Network: You are both a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and a novelist. Why did you choose the novel form to tell this frank story of what life is like for Muslim Americans in 21st-century America?

Ayad Akhtar: Choice is a big word! The form usually finds itself, without much choosing on my part. Here was no exception. The sentences that poured out of me were long and rich, and only pointed to it being a novel, though for a couple of days, I wondered if it was a monologue of sorts. And I guess that is what it ended up being: a voice, speaking, to a reader, in the form of a novel.

TBRN: Your protagonist, who shares your name and whose life shares important details with yours, says to “point away from the work back to the life of the one who created it only undermines the particular sort of truth that I believe art is after.” That said, how would you respond specifically to those who will read HOMELAND ELEGIES as disguised autobiography?

AA: I will be happy! The book plays with reality and illusion, and is an attempt to find a texture that reflects the confusion around fact and fiction that has overtaken our societies. To read it simply as veiled autobiography would ultimately be to miss the point --- but the experience of missing the point, and then wondering, well, that would be the larger point!

TBRN: The novel vividly portrays the tension between Ayad’s immigrant parents in their respective views of their two homelands --- Pakistan and America. Do you sense that is a widespread tension in Pakistani American families?

AA: I can only speak for my family and those I know. But it wouldn’t surprise me. Also, it’s important to recognize that I’m a dramatist. So I am drawn to opposition and conflict. And where those dynamics can be enhanced, I will almost always choose to do so.

TBRN: Two characters --- Pakistani American hedge fund manager Riaz Rind and Black Hollywood agent Mike Jacobs --- both of whom are wildly successful and deeply cynical, offer blistering critiques of American capitalism. And yet, Ayad and his family have achieved what many would consider a significant portion of the American dream under that system. How do you reconcile those perspectives?

AA: The narrator’s father ends up broke at the end of the book, so it might not be entirely accurate to say that he achieved that dream ultimately. As for the narrator, well, yes, he partakes, unwittingly, in predatory financial practices, and becomes rich. And that is a problem for the book, as a metaphor and as a moral conundrum. And one that I hope the reader will not let him off the hook about!

TBRN: You write that “money had always been central to notions of American vitality, but now it reigned as our supreme defining value. It was no longer just the purpose of our toil but also our sport and our pastime” (a passing reference to the Quran). Do you see Islam and American capitalism as irreconcilably in conflict?

AA: I’m not sure that’s the opposition I would choose to highlight. How about this one: Christianity and the example of Christ are irreconcilable with the very American capitalism that so many see, oddly, as somehow sanctioned by that faith!

TBRN: Riaz also doesn’t spare Islam from criticism, describing its fixation on a “Golden Age” and complaining about “how we fell so far behind.” Do you believe that criticism can be leveled in any way against Muslim Americans?

AA: That’s not exactly what Riaz says. In the section you’re referring to, Riaz is trying to account for the argument of the narrator and acknowledges what is a demonstrable fact: That the West has material ascendancy. For Riaz, it’s not a criticism, but an observation. Moreover, what Riaz suggests is that the Islamic world is behind materially because it cared more about people than money. So he turns what the narrator is saying into a positive story about Islam, which is what he’s always doing!

TBRN: The encounter between Ayad and a Pennsylvania State Trooper when Ayad’s car breaks down on the interstate and the officer surreptitiously probes for evidence that Ayad may have ties to terrorism is a chilling one. What parallels, if any, do you see between that incident and similar encounters between Black Americans and the police?

AA: While the narrator certainly felt a threat, his life was never really in danger. If the narrator had been black, he might well not have survived the encounter. That’s the fundamental difference I see.

TBRN: The novel includes a conversation between Ayad and a cab driver of Italian heritage who alludes to prejudice against previous waves of immigrants. How does current anti-Muslim prejudice differ from bigotry directed toward those earlier immigrants, and in what respects is it similar?

AA: It’s a good and important question, and I’m not sure I have a great answer to it. As targets of American foreign policy for more than 20 years now, Muslims are in a position of being seen as enemies of the state, and that may begin to define a difference in the nuance here.

TBRN: In a similar vein, Ayad addresses what he calls the “paradox,” that “in order to flourish in this new land, we had to adopt its Christian ways, ways that befuddled us and that we disdained, ways we saw reflected in almost every aspect of American life.” How is that different from the dilemma of assimilation facing some earlier generations of immigrants to America?

AA: Another great question. I think each group probably has its own challenges, given its history and background.

TBRN: One of the book’s most powerful scenes is Ayad’s description of his experience in Manhattan on 9/11, a day he thinks of as a “reminder of our repulsive condition, at once suspects and victims when it came to this, among the greatest of American tragedies.” As a writer, describe how you went about recreating the terrible sights and overwhelming emotions of that day.

AA: My job is as an artist and dramatist, so the rules of engagement are formal. They have to do with keeping an emotion building, in shaping the narrative in ways that rhythmically move to greater and greater integration and meaning. In the case of the 9/11 narrative, I had been gathering observations and stories for years, and finally, in writing this book, all that material was able to get distilled into the 3,000-word passage you’re describing. I wanted it to feel up to the challenge of embodying that day, to encompass not only a story that contained a larger experience than my own, but one that could enfold the reader’s experience of trauma into it as well.

TBRN: In describing the “disbelieving white gazes” that he, his father and his father’s Pakistani American friend receive at the Milwaukee airport, Ayad wonders, “How was it possible people who looked like us would not be eternally subdued by the fact of their unceasing suspicions?” What do you think it will take for those who harbor such suspicions to view Muslims with less hostility?

AA: Probably familiarity. We are a tribal species. We are naturally suspicious of those we consider other. I don’t think it’s a crime. I think it’s something that gets overcome through familiarity and time.

TBRN: Over the course of the novel and the Trump presidency, Ayad’s father undergoes a painful transformation from an ardent American patriot to someone who is deeply troubled by what’s going on in this country. How difficult do you think it has been for people like him who have made that transition?

AA: I think so many of us are still in denial about what has been happening here. Of course, the causes of this advanced decay to our republic, if you will, are not new --- but all the same, the pandemic has laid bare the disrepair. What will it take for us to solve it? I worry that our denial may not allow us to. And I do tend to see the flavor for conspiracy theory connected to this increasingly widespread denial.

TBRN: Why do dreams and our ability to remember them play such a key role in the novel? Is that an important element in your fiction?

AA: Dreams play a pivotal role in HOMELAND ELEGIES and form the basis of the book’s approach to structure. A kind of vivid labyrinthine immersion that, I hope, absorbs the reader in its ever-growing network. Like the cover of the hardcover --- a system of roots.

TBRN: The concluding sentence of HOMELAND ELEGIES is “America is my home.” Do you see that sentiment as a permanent, or merely a provisional, one for Ayad?

AA: It is the narrator’s home, and mine. It always has been and always will be. Not that this isn’t without complications. But those complications don’t make it any less a home.