Excerpt

Excerpt

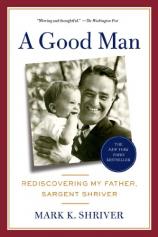

A Good Man: Rediscovering My Father, Sargent Shriver

Introduction

I was anxious and my heart was pounding as Dad and I drove east on Route 50 toward the Chesapeake Bay. We were running late—not unheard of in my family but unacceptable to the hunting guides of Maryland's Eastern Shore, who always insisted on a predawn rendezvous. Dad was doing his best to make up for lost time by obliterating the speed limit, but we were still behind. As we slowed to pay the toll, I could feel the cool autumn air and already see the streaks of sunrise on the horizon—and we still had forty minutes to go.

These hunting trips were a ritual for us, but my postcollege life—a new job, new commitments, maybe even new priorities—was starting to disrupt the regularity of our father-son reunions. And as the hum from the tires changed pitch when we began to cross the giant steel bridge that traverses the Chesapeake, I grew more irritated with Dad.

He knew that I was working grueling hours at a nonprofit I'd started in Baltimore and that it was hard for me to get away from those responsibilities. And as a lifelong hunter and Marylander, he knew the birds started moving early, and was well aware of the guides' protocol. Nonetheless, he'd been close to a half hour late.

We ascended the bridge's incline in silence, I quietly stewing and Dad lost in his own thoughts. By the time we got to the midway point of the four-mile-long steel structure, the full expanse of the choppy bay below and the low-lying shore ahead were beginning to be illuminated by the morning sun.

The birds will already be flying, I thought to myself. I was growing more annoyed just as Dad, staring out at the same daybreak, suddenly broke the silence, his thoughts far from that day's hunt. "Look at that!" he cried, awestruck. "I can't wait to meet God. I can't wait to meet the Creator who made such a beautiful sunrise!"

Staring out the side window I mumbled a sarcastic response: "Yeah, it's beautiful, Dad. Thanks for pointing it out."

Moments later, as we reached the final expanse of the bridge, it felt as if we were driving straight into the rising sun, massive and reddish yellow over the Eastern Shore, waiting to swallow us up at the end of our crossing.

I looked over at Dad, his face awash in the bright light. He was staring straight into the sun in a state of awe, eyes wide and unblinking. I could tell he was repeating to himself over and over what he'd just exclaimed aloud: I can't wait to meet the Creator who made such a beautiful sunrise... I can't wait to meet God...

We finally made it to the ragged cornfield, a bit behind schedule but not so late as to cause any real problems. Dad was in a typically buoyant mood all morning. He chatted incessantly with our two guides in the goose blind, asking about their lives and families and cracking jokes and becoming fast friends in no time, as only he could. And when the geese finally came in close, he couldn't contain his excitement, and he whooped and cheered us on—causing the first gaggle we saw to reverse course and fly off to safety.

Our attempts to get him to shush fell on deaf ears. He kept talking and laughing, at one point breaking out a Snickers bar, taking a hearty bite, and sincerely reacting as if it were a rare delicacy. "This is absolutely terrific!" he half-whispered. "Who wants to try a bite?!" Our guides shook with laughter, which only made his smile broader.

Somehow we managed, despite Dad's antics, to get a few geese that morning. I don't think Dad pulled the trigger once, though, preferring instead to watch and congratulate everyone else with a slap on the back. "My God!" he'd shout. "What a fantastic shot! You are a magnificent waterfowl hunter!" His mood was contagious, and everyone—me included—had a wonderful time.

But I was still anxious. No longer because of his late arrival but because of a contradiction I'd never been able to figure out about my father, one that had been demonstrated to me so starkly in the span of a few hours. His infectious cheer that morning stood in glaring contrast to his startling comment on the bridge earlier: "I can't wait to meet God." I knew Dad's faith was unshakable, that he went to daily Mass without fail, and that his great loves in life were God and my mom. But how could someone so full of life be so ready for death? Not fearful of it but almost longing for it? How could he, quite literally, be excited to die?

He was seventy-three, but you'd never know it. He possessed the energy of a teenager, he looked half his age, and his remarkably full and active life had shown no sign of slowing down. As he had throughout so much of his life, he was getting important things done—still traveling the world, meeting prime ministers and presidents, working tirelessly and effectively to open the doors of freedom and opportunity for people who had historically been denied those things. He was constantly surrounded by his children and their growing families, he was more helplessly in love with his wife of thirty-five years than ever before, and everywhere he went he saw old friends and made new ones. He had his health, financial security, and, at this point in his life, the freedom and ability to do whatever he chose.

And yet he could stare into the sun and tell his fourth-born child that he couldn't wait to leave it all behind. I simply couldn't balance the two extremes: why was my dad, a guy so filled with vitality, looking forward to his own death?

Fast-forward twenty-two years. My mom, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, had died a year earlier, on August 11, 2009, and my dad was engaged in a heroic but losing battle with Alzheimer's. His doctor had told my siblings and me that, at ninety-four, Dad would probably not live more than another twelve to eighteen months. When we related this to Dad's lawyer, Bob Corcoran, he reminded us that, some thirty years earlier, Dad had written a letter that he'd asked Bob to hold until his death. We thought that, given all the decisions that had had to be made in a tight time frame after Mom's death, we should know whether Dad had left specific instructions about his wake, funeral, burial site, and so on.

So in August 2010, Bob sent us the letter, which landed at the family home in Hyannis Port like a stealth rocket amid the chaos of five children, four in-laws, nineteen grandchildren, and Dad himself. Everyone was running in different directions, playing tennis and baseball and sailing.

I noticed an open FedEx envelope on the counter and asked my brother Timmy whether the letter was in it. He said yes, that he'd opened it and read it, then left it for the others. I read it, quickly, and was moved by its beauty and thoughtfulness, but shortly after I finished, my kids pulled me away. I set the letter aside, determined to go back to it in more serene moments. That serenity never came.

Three months later, Dad celebrated his ninety-fifth birthday in style. We had a party for him at our house. Grandkids ran all around and took turns sitting on Dad's lap. We laughed and sang. Dad smiled and shouted out a few words of joy. He opened his presents and gobbled up his cake and ice cream. It was a great night, but he was clearly slipping. The letter crossed my mind—I have to find a quiet time to really read it, I thought.

The rest of November and December were jam-packed with Thanksgiving and Christmas and family visits. Work was as crazy as ever—I was running Save the Children's U.S. Programs and on the road at least two days a week, pitching prospective donors, lobbying state and federal elected officials, and seeing the kids in our programs. My own kids' sporting events consumed the weekend—we were busy doing everything we could to keep up with the Joneses.

Even though Dad lived less than three miles from us, I didn't see him as much as I wanted to, or should have, because, well, life with three kids and a wife, a job requiring lots of travel, and other commitments spread me too thin. And there was, of course, Alzheimer's. For almost ten years I'd been in charge of Dad's finances and medical care. Each small step in his decline became another devastation for me, from taking away his car keys to hiring an assistant and then full-time providers; from explaining Mom's death to him to moving him out of their home. Our visits together could still be enchanting, especially when my kids were with me, but it was painful to see the brightest, most inquisitive, most joyful person I knew struggle to piece together short sentences. When Dad smiled and told the kids or me that he loved us or that we were wonderful, it made me happy—but it also made me miss him even more.

So, in early January, as I packed for a flight to Los Angeles for a Save the Children event, I remembered to take the letter with me. Dad's doctor, on our last call, had made it pretty clear that Dad was not going to live to see ninety-six. He had just reentered the hospital for the second time in a month. I didn't think he was going to die in the next few days, but I wanted to read the letter again and jot down a few thoughts in case I had to give a eulogy.

I had a window seat, and as the plane took off from Dulles International Airport, we headed east, toward the Chesapeake Bay. I realized the pilot was following air traffic control's direction before banking south and then heading west. But he sure seemed to be taking his time doing it.

Then I looked out the window, and the memory smacked me in the face. There was the Bay Bridge, there was the hearty, glowing sun, and there were Dad and I driving that morning so many years ago.

I pulled out the letter and started to read. Maybe it was because I knew his death was so imminent, or maybe it was sitting alone in an airplane away from my family; whatever it was, the letter overwhelmed me. He had written it in 1979, at the age of sixty-four. Why would a man so relatively young and vigorous be thinking about death—telling us the mechanics of his burial, his intended preparations in heaven for Mom and even for our eventual arrivals there, his eternal love for Mom and each of us? He was thinking about these things a decade before our Bay Bridge crossing. Why would he write such a note, drenched with mortality, to his wife and five children? He'd added a P.S. to the letter in 1987, at the age of seventy-two, and said that he was still in agreement with everything he had written earlier.

I pulled out a pad and started to write. I wanted to put some thoughts on paper about my father, his eventful life, and his commitment to public service. I wanted to somehow convey who I thought he was, not just as a public man but, more importantly, as a father, husband, and friend.

Four days later, I received the long-dreaded call from Timmy—Dad was slipping, and it was a matter of days. I had to return home from California immediately if I wanted to see him before he died.

The days leading up to his death were filled with Rosaries and Masses by his bedside, with final good-byes by all of the kids, grandkids, and in-laws. My siblings—the oldest, Bobby; my older sister and brother, Maria and Timmy; and my younger brother, Anthony—and I spent time together and started planning the wake and funeral.

The busyness of funeral planning, I hoped, would keep me from my grief for the time being. But the process itself became an education that would change my life. From encounters and discoveries over the next few days, I began to get the sense that Dad really wasn't who I thought he was—that he was far more complex and intriguing. I began to realize that the circumstances of the last ten years—including my congressional race and all the details of tending to Dad as he struggled with Alzheimer's—had kept me from exploring, let alone understanding, my father's insistent joy, powerful faith, generous spirit, and hopeful view of life.

I'd lost track of who he was, what he'd done, and what he'd said and written. He wrote me a letter almost every day of my adult life, many by hand, most typed. Some I read quickly; some I put in a file to be read later and never got back to. I had not mined all this material, which could have enriched my own outlook on life. His life was a treasure trove of moral examples and ethical inspiration, but in my hustle and bustle, I had failed to identify this spiritual guide living right before my eyes. Straying into the dark woods of ambition and self-involvement, I was losing track of the principles that defined his every day.

The letter had shaken me out of this ten-year fog—and other experiences were now following furiously.

I was tasked with picking the coffin. Dad had made this job easier for me per the directions in his final letter—he wanted to be buried in a sack, like the Trappist monks he so admired.

When I tried to satisfy this request, I learned that the government prohibited such interment for public health reasons, but I did find that Trappist monks in Iowa were building coffins. I studied the website and chose a walnut box, finely crafted but simple. I phoned the monks to go over the details; a little while later, the director called me back and told me that he had met Dad once and would do whatever I asked. He said that it would be an honor to help because Dad was such a "good man."

Over the coming days, I heard that phrase time and again. That old cliché—"a good man"—suddenly became confounding to me. I heard it so often during the days before the funeral that it passed from a cliché to an irritant to a haunting refrain.

The phrase had been used by the Bush administration to describe Michael Brown, the head of FEMA during Hurricane Katrina, and Russian president Vladimir Putin. It had grown stale, like an old cowboy line in a spaghetti western on insomniac television.

I had lost count of the people who had applied it to Dad when they'd reached out to me. At first, I thought that the cliché was just an easy out, words for people who didn't know what else to say.

But then I realized that they were taking the phrase back. Through their repetition, if not their realization, they were redeeming words that I thought had been put out to linguistic pasture.

Some of the more startling instances came back to me as I knelt in the dark beside Dad's coffin on the morning of the funeral. A prominent U.S. senator who knew Dad well, yet obviously didn't know him as well as he thought he had, told me, "I knew your dad had done a lot, but he did much more than I had known. He was a good, good man."

Ms. Wilson and Ms. Williams, both of whom waited in the wake line at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown for forty-five minutes told me that they were waitresses at Reeves Restaurant, Dad's regular lunch spot across from his office. And before that, Ms. Wilson had waited on him at the Hot Shoppes in Bethesda for thirty-five years. They wanted to tell me that they had never met a more polite, thoughtful man in their forty years of work. "He was such a good man," they said simultaneously.

I will never forget the rumble of the garbage truck outside my house on the day of the wake and seeing Calvin, the trash collector, standing in our driveway, trying to decide whether to walk up to the front door and knock. I made it easy for him; I was on the lawn and went toward him. He had tears in his eyes. He took off his dirty gloves, wiped his palms on his work clothes, and reached out his hands for mine.

"What a life," Calvin said. "I read about your dad in the paper and, man, I had to put the paper down. I had to take a step back—whoa! He helped so many people—what a good man!"

I also couldn't shake my conversation with Edwin at the wake. He worked for US Airways and had crossed paths with Dad many times during those years of travel. Not long ago, he'd seen Dad struggling and had spent half an hour helping him get through the security line. Edwin waited in that line at the wake, too, and told me that those thirty minutes were some of the most special ones in his life.

"I never met anyone in all my years like your father," he said. "He was such a good man."

Brad Blank, a childhood friend of mine from Cape Cod, called and told me that Dad had written him thoughtful letters a number of times over the years. He'd even discussed the Judaic Studies program at Brown with Brad, saying it surpassed courses in Christianity there.

Brad said, "Your father knew more about Judaism than I do. He was such a mensch. Do you know what that means?" Before I could respond, he blurted out, "It means your father was a good man."

Throughout the planning of the funeral, Jeannie Main, Dad's longtime assistant, was at every meeting. I asked her, finally, how long she had worked with him.

"Thirty-three years," she said. "I volunteered on the McGovern-Shriver campaign in '72 and went to work for him full-time afterward."

"That's a long time," I said.

"Yes, it is, but your dad was special," she said. "Not too many big-time lawyers would listen to their assistants. Your dad always did. He didn't always agree with me, but he always listened. He was a very good man."

We got a call from Vice President Joe Biden a few hours after Dad died. The vice president told me that he never would have won his race for Senate in 1972 had Dad not shown up on the last night and rallied a crowd that worked through the night and all Election Day. Biden won by 3,162 votes, and he credited Dad with the difference.

"He didn't have to do that for me," he said. "I was an unknown kid who wasn't expected to win. Delaware is a small state, and it was the last night of a long campaign. There wasn't much, if anything, in it for him. But that was the least of what he did for our country—he was a good, good man."

Then I thought about our kids and how, just the day before, I had watched them eat breakfast with their usual gusto. When my eleven-year-old son Tommy got up and took his plates to the sink and started washing them, I almost lost it, remembering how, two years prior, Tommy had watched Dad, Alzheimer-stricken and hobbled, grab his own cake plate after the party for his ninety-third birthday, take it to the sink, and clean it. Tommy had looked at me, licked the icing off his last forkful, and followed Dad to the sink with his plate. Tommy had observed, at a very young age, what a good man Dad was, right down to the smallest detail of etiquette.

The great man is recognized for his civic achievements. The good man can be great in that arena, too, but even greater at home, on the sidewalk, at the diner, with his grandkids, at the supermarket, at church—wherever human interaction requires integrity and compassion. Dad was good because he was great in the smaller, unseen corners of life. He insisted on greatness in every facet of the daily grind. Nowhere was this clearer than in his role as our father.

During the weeks and months after the funeral, the same sort of condolences kept piling in. The "good man" phrase kept cropping up, and I realized how important it was becoming for my own life, and perhaps for all those who wanted to know how Dad lived so well, to understand him more completely. We all loved reflecting on his life together, yet most of us—family and friends and complete strangers who had admired him from afar—were looking to solve the riddle of "Sarge" for our own sakes. We wanted some of that; we wanted to bottle his mojo for ourselves.

I received thousands of letters and e-mails—many from people I didn't know at all and many from those I knew well who, after reading about Dad or attending his funeral, opened their hearts to me. So many were struggling to balance their love of family with their work, struggling with their faith, struggling with giving back to their communities. I realized that I, too, was struggling mightily with balancing it all. What's more, I had spent far too much time and energy chasing the illusory achievements that our culture associates with being a so-called great man.

One person who attended the funeral told me that he had never been in a church for two and a half hours but that at the end of Dad's funeral, he didn't want to leave. Most seemed to dearly want to be a good man or a good woman, and they kept asking me questions: How did your dad do it all? How could he have been happily married for fifty-six years and yet there'd never been even a rumor about his relationship with my mother? How could he have raised five children who all idolized him? Been a steadfast friend to so many men and women? How could he have created, out of nothing, the most enduring legacy of the Kennedy administration—the Peace Corps—and then, while still the head of the Peace Corps, created Lyndon Johnson's most important domestic initiative, the War on Poverty—Head Start, Job Corps, VISTA, and Legal Services, to name just a few programs? And every day he went to Mass!

This book is the story of the journey I immediately undertook—was driven to undertake—to discover how a ninety-five-year-old man who had been crushed in his two national election races (for vice president with George McGovern in 1972 and for president in 1976), who had not run for office in over thirty-five years, who had been battling Alzheimer's for ten years, nevertheless inspired countless others to live a good life.

I worked, with a relentless, consoling, and consuming need, to understand the lessons of his life and his final struggle with Alzheimer's—lessons about the durability of faith, the endurance of hope, and the steadfastness of love. How had he been so faithful? So hopeful? And so loving? These were the three guiding principles of his life—faith, hope, and love—and I needed to get to the source of them.

Most of all, I wanted to understand the riddle of his joy. I knew that his uncanny, boundless joy had powered him every day of his life. Where did it come from? How did he sustain it, gracing so many of us along the way? For my family and friends, for his admirers, and for me, I wanted to discover the source of his joy so we could all try to live the same way, so I could use him as my guide as I strove to be a better man, to be as good a man as he.

A Good Man: Rediscovering My Father, Sargent Shriver

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: St. Martin's Griffin

- ISBN-10: 1250031443

- ISBN-13: 9781250031440