Excerpt

Excerpt

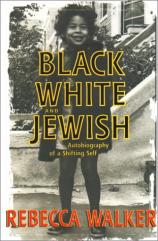

Black White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self

On my first birthday I am given my favorite foods: chitterlings and chocolate cake. Daddy goes to Estelle's, the soul food place on the other side of town where he is the only white customer, and brings me home a large order of the pig intestines. Mama puts me in my big wooden high chair with the smooth curved piping, and then feeds me one slimy pale gray glob after another while Daddy sits at the table, grinning.

After I have eaten all of the chitterlings, Mama has to peel my tiny fingers from the container to make me let it go. Then she sets a chocolate cake with a big number one candle sticking up from the middle down in front of me, singing "Happy Birthday" softly, so that only I can hear. For a few seconds Mama and Daddy wait, expectant and wide-eyed, to see what I'll do. I giggle, squeal, look at them, and then dig into the cake with my bare hands, smearing the sticky sweetness all over my face and pushing what's left into my mouth. I rub cake in my hair, over my eyes. I slap my hands on the high chair, putting some cake on it, too.

My parents laugh out loud for a few seconds; then my father wraps his arm around my mother's waist, patting her hip with a cupped hand. For a few seconds we are frozen in time. Then my father pushes his chair out from the table, cuts himself a piece of the chocolate cake, and goes to work.

You may want to ask about the story of your birth, and I mean down to the tiniest details. Were you born during the biggest snowstorm your town had seen in fifty years? Did your father stop at the liquor store on the way to the hospital? Did you refuse to appear, holding on to the inside of your mother's womb for days? Some sinewy thread of meaning is in there somewhere, putting a new spin on the now utterly simplistic nature-nurture debate. Your job is to listen carefully and let your imagination reconstruct the narrative, pausing on hot spots like hands over a Ouija board.

I was born in November 1969, in Jackson, Mississippi, seventeen months after Dr. King was shot. When my mother went into labor my father was in New Orleans arguing a case on behalf of black people who didn't have streetlights or sewage systems in their neighborhoods. Daddy told the judge that his wife was in labor, turned his case over to co-counsel, and caught the last plane back to Jackson.

When I picture him, I conjure a civil rights Superman flying through a snowstorm in gray polyester pants and a white shirt, a dirty beige suede Wallabee touching down on the curb outside our house in the first black middle-class subdivision in Jackson. He bounds to the door, gallantly gathers up my very pregnant mother who has been waiting, resplendent in her African muumuu, and whisks her to the newly desegregated hospital. For this final leg, he drives a huge, hopelessly American Oldsmobile Toronado.

Mama remembers long lines of waiting black women at this hospital, screaming in the hallways, each encased in her own private hell. Daddy remembers that I was born with my eyes open, that I smiled when I saw him, a look of recognition piercing the air between us like lightning.

And then, on my twenty-fifth birthday, Daddy remembers something I've not heard before: A nurse walks into Mama's room, my birth certificate in hand. At first glance, all of the information seems straightforward enough: mother, father, address, and so on. But next to boxes labeled "Mother's Race" and "Father's Race," which read Negro and Caucasian, there is a curious note tucked into the margin. "Correct?" it says. "Correct?" a faceless questioner wants to know. Is this union, this marriage, and especially this offspring, correct?

A mulatta baby swaddled and held in loving arms, two brown, two white, in the middle of the segregated South. I'm sure the nurses didn't have many reference points. Let's see. Black. White. Nigger. Jew. That makes me the tragic mulatta caught between both worlds like the proverbial deer in the headlights. I am Mammy's near-white little girl who plunges to her death, screaming, "I don't want to be colored, I don't want to be like you!" in the film classic Imitation of Life. I'm the one in the Langston Hughes poem with the white daddy and the black mama who doesn't know where she'll rest her head when she's dead: the colored buryin' ground behind the chapel or the white man's cemetery behind gates on the hill.

But maybe I'm being melodramatic. Even though I am surely one of the first interracial babies this hospital has ever seen, maybe the nurses take a liking to my parents, noting with recognition their ineffable humanness: Daddy with his bunch of red roses and queasiness at the sight of blood, Mama with her stoic, silent pain. Maybe the nurses don't load my future up with tired, just-off-the-plantation narratives. Perhaps they don't give it a second thought. Following standard procedure, they wash my mother's blood off my newborn body, cut our fleshy cord, and lay me gently over Mama's thumping heart. Place infant face down on mother's left breast, check blankets, turn, walk out of room, close door, walk up hallway, and so on. Could I be just another child stepping out into some unknown destiny?

Jackson

My cousin Linda comes from Boston to help take care of me while my mother writes and my father works at the office. Linda has bright red hair and reddish brown skin to match. Linda sits on our tiny porch for hours, in the same chair Daddy sits in sometimes with the rifle and the dog, waiting for the Klan to come. Linda sits there and watches the cars go by. When she sees the one she wants, she stands up and points. She says she wants a black Mustang, rag top. "That car is live," I say, putting extra emphasis on live but not sounding quite as smooth as my cousin. "Rag top," I say, trying it on as we sit together on the cement porch.

Linda gets sick after a few weeks and can't get out of the extra bed in my room. She tells me secretly, late at night from underneath all our extra quilts and afghans, that she wants to stay here with us forever, that she loves Uncle Mel, wants to marry Uncle Mel. She says, "Your daddy is a good white man!" and smiles, her big teeth all white and perfect.

Linda is sick for a long time. Does she have the mumps, tonsillitis? Daddy says it's because she doesn't want to go home. Mama ends up taking care of both of us. She boils water in the yellow kettle and makes Linda honey and lemon tea, Mama's cold specialty. She tells me and Linda to lie on the brown sofa in the living room, in the sun. Linda lies one way on the corduroy couch, I the other. Before she goes back into her study, Mama covers us with the big, colorful afghan.

Linda and I stay there, whispering, and tickling each other with our toes until it is dark, listening to the click-clacking of Mama's typewriter, until we see the shadowy outline of Daddy walk through the front door.

Mrs. Dixon comes twice a month to vacuum our house and clean the kitchen and bathroom. She is tall and light-skinned and wears her hair pulled back in a bun. She is older than Mama, and very quiet. I know she is in the house only because of the sound of the vacuum cleaner, which seems especially loud in our house that is usually so still and silent.

Sometimes, after Mrs. Dixon goes home and leaves the house with a clean lemony smell, Mama puts on a Roberta Flack or Al Green record and runs a bath for us. After we scrub and wash with Tone soap or Dial, we spread our bright orange towels out in the warm patches of sunlight that streak the light wood of the living-room floor. We rub cocoa butter lotion all over our bodies and then do our exercises, leg lifts, until our legs hurt and we can't do any more. Sometimes we fall asleep there, after the arm on the phonograph swings itself back into place, my little copper form pressed against the smooth warm length of my mother's cherry-brown body.

Grandma Miriam comes for a visit. She says she can't stay away from her first-born, oldest grandchild. She drives up in her yellow Plymouth Gran Fury and right away starts talking about all the things we don't have and what is wrong with our house. She buys Mama a washer-dryer in one and a sewing machine. She buys me a Mickey Mouse watch that doesn't stay on my wrist. It is way too big, but she says I will grow into it. She also buys me a package of pens with my name printed on them in gold.

Grandma Miriam is so strong, sometimes when she picks me up it hurts, holding too tight when I want to get down. She also walks fast. She also always turns up our air conditioner because she says it is too hot "down here." She lives in Brooklyn, the place where Daddy was born. She brought all of her clothes and presents and everything in a round red "valise" with a zipper opening and a loop for a handle. She has white skin and wears red lipstick and tells me that the nose she has now is not her real nose. When I ask her where her real nose is, she tells me, "Broken," and then right away starts talking about something else, like the heat.

Daddy seems happy Grandma came to see us, but Mama seems nervous, angry. I think this is because Grandma doesn't look at Mama. When she talks to Mama, she looks at me.

. . .

Mama has to have an operation on her eye. She leaves early one morning and doesn't come home until late the next day. I wait, listening all afternoon for her key in the lock. When the door finally swings open and I see the sleeve of her dark blue winter coat, my heart jumps. I want to run into her arms, but something stops me. Mama has a big white patch over her eye. She looks different, like the side of her body with the patch is lost, not there, or in the dark. Suddenly I am afraid that if I am not gentle, I will knock her down.

I must look worried because she smiles her big smile and tells me that she's all right. The operation wasn't as bad as she thought it would be.

I almost believe her.

Later, as she dresses to go out, Mama opens her straw jewelry basket and searches for a necklace to wear. I watch her, face resting in my upturned hands, as she tries first the heavy Indian silver amulet and then a simple stone on a leather strap. I notice that she holds her head a new way, hurt eye away from the mirror and chin slightly down.

After choosing not to wear either, she turns and kisses my forehead. Looking deep into my eyes she tells me that one day, all of the jewelry in the basket will belong to me.

Almost every week people come to our house to visit. They come from up north, they come from other countries. They come to see us, to see how we are living in Jackson. Most people bring presents for Mama: books, teas, quilts, bright-colored molas from Central America she puts on the walls. When my cousin Brenda comes, she brings presents for me. She brings soaps shaped like animals, puzzles with animals in them, books about animals, and my favorite, sheets with animals crowded onto them in orange, red, and purple packs.

Late at night between my jungle sheets, I imagine I am riding on the backs of giraffes and elephants, I imagine I can hear the sounds of the wild, of all the animals in the forest talking to one another like I have seen on my favorite television show, Big Blue Marble. When Mama comes in to check to see if I am asleep, I am not, but I shut my eyes tight and pretend that I am so that I can stay in the dark dark forest where it is moist and green, where I am surrounded by all my friends from the jungle.

Three days a week I go to Mrs. Cornelius's house for nursery school. Most often Daddy drops me off on his way to the office, or sometimes Mama will take me up the street, or Mrs. Cornelius will send her daughter Gloria to pick me up. Mrs. Cornelius's school is in her basement, which she has renovated with bright fluorescent lights, stick-down squares of yellow and white linoleum, and fake dark wood paneling.

Every day at lunchtime at Mrs. Cornelius's, we eat the same foods: black-eyed peas, collard greens, and sweet potatoes. I start to hate black-eyed peas from having them so often, but I love Mrs. Cornelius. She is like Grandma, only warmer, softer, and brown. She always pays special attention to me. On picture day she combs my hair, smoothing it away from my face. She says that I am pretty, and that even though I am the youngest at her school, I am the smartest. In the class picture, mine is the lightest face.

One day Daddy holds my hand as we cross the street in front of our house like usual, on our way to school. I am wearing my favorite orange and red striped Healthtex shirt and matching red pants with snaps up one leg. Suddenly Daddy stops and points in the direction of Mrs. Cornelius's house. He looks at me: "Do you think you can walk by yourself?"

With my eyes I find Mama, who waves and smiles encouragingly from the porch. "Don't worry, I'll watch you from here," Daddy says, but I'm already confused. He pats my backside. "Go on. Go to Mrs. Cornelius's house." I feel trapped, uncertain, and so I just stand there, looking first at Daddy and then across the street at Mama. Before I can say anything, Daddy nudges me again and I take a tentative step toward Mrs. Cornelius's house, my shoes tiny and white against the dirty gray pavement.

One night after I am supposed to be in bed, I crawl into Mama and Daddy's room, making my way around their big bed where they lie talking and reading the newspaper. Johnny Carson is on the television, and every few minutes Mama laughs, throwing her head back. From where I sit, underneath the little table by Mama's side of the bed, I can see the television, but not much else. I watch and watch quietly until I forget where I am and what time it is and hear myself laugh out loud at Johnny Carson. He has put on a silly hat and robe and is waving a magic wand. For a second everything in the room is quiet, and then Daddy swoops down from nowhere and asks me what I am doing, how did I get under this table, why am I not in bed. He is trying to be serious, but he and Mama are laughing even while they try to pretend to be mad. Daddy reaches for me and says, I AM GOING TO SPANK YOU! But I am already running, giggling so loud I can hear myself echo through our dark house, my socks sliding against the wood floor as I make my way to my bed.

When I am almost there, when my feet slide over the threshold of my bedroom door, Daddy catches me and swings me up over his shoulder, tickling me and telling me I should have been asleep long ago. I can barely breathe I am so excited. It is past my bedtime and I am out of breath and high in my daddy's arms, caught doing something I shouldn't. My heart races as I squirm to get down. Will Daddy really spank me? When we get to the edge of my bed, Daddy stands there for a few seconds, letting me writhe around in his strong arms. When I quiet down a bit, he smacks my upturned butt, his big hand coming down soft but firm on my tush. We both laugh and laugh at our hysterical game, and after he throws me down on my bed and tucks me in, kissing my forehead and telling me that I am the best daughter in the whole world and he loves me, I lie awake for a few minutes, a grin spread wide across my face.

It is poker night at our house. Daddy and a bunch of other men sit around the dark wood captain's table in the kitchen, laughing and smoking. Each player has a brightly colored package of cigarettes close by, a red or blue box that says Vantage, Winston, or Kool. Until it is time for me to take a bath, I sit on Daddy's lap picking up red, blue, and white plastic poker chips and dropping them into slots in the round caddy. It is hot and I'm wearing one of Daddy's tee shirts that comes to my knees. The back door is open. It is pitch black outside. Steamy pockets of air seep in through the screen.

Mama walks into the kitchen to put her big, brown tea mug in the sink. She wants to know why they aren't playing over at Doc Harmon's place, in the room behind his drugstore, like they usually do. The men, Daddy's law partners, one of whom will later become the first black judge in the state, and another the first black elected official, and a few other white civil rights workers from the North like Daddy, chuckle, glance at each other from behind their cards. "What's the matter, Alice, you don't like us over here? Hmmph. And we heard you wanted your husband at home for a change."

But Mama isn't fooled. She sees the rifle leaned up against the wall behind Daddy. The Klan must have left one of their calling cards: a white rectangle with two eyes shining through a pointed hood, THE KLAN IS WATCHING YOU in red letters underneath. She eyes the screen door, checks to see that it's locked, while my naked mosquito-bitten legs swing carelessly back and forth from up high on Daddy's lap.

Before I go to sleep, Daddy takes a "story break" from his poker game to tell me my favorite story about the man who lines up all the little girls in the world and asks my father to choose one. In my mind the guy who lines us all up looks like the guy on television, the man from The Price Is Right. Mr. Price Is Right beckons for my father to "step right up" and have a look at "all the girls in the world." My father walks up slowly, cautiously looking at Mr. Price Is Right as he puts his hand on my father's elbow. "Mr. Leventhal," he says, "you can have your pick of any girl you want. I have some of the best and brightest right here." For a second my father mocks interest. "Really?" But then Mr. Price Is Right shows his cards. "Yep. The only catch is that I want to keep Rebecca for myself."

Suddenly my father's body stiffens up and he shakes his head adamantly. "Oh no," says Daddy, "that won't do at all." And then he's angry. "Where is she?" he demands, already starting to walk down the line of little girls stretched out seemingly forever. "Where is my Rebecca?" Mr. Price Is Right doesn't know what to say. He hopes that if he doesn't answer, my father won't find me and he'll be able to keep me. But, my father says, turning to me all tucked into my jungle sheets, what Mr. Price Is Right doesn't know is that my father will always be able to find me, he's my father and I'm his daughter. We can always find each other.

So he walks and walks down the long line of little girls of every size and color, each girl calling out to him and trying to convince him to take them, until at last he finds me. His eyes light up as he takes my hand and leads me out of the line. Of course, Mr. Price Is Right runs over and tries once more to convince my father to leave me. "Oh please, Mr. Leventhal, look at all these other girls. Surely one of them will be just as good a daughter for you?" But my father is firm, shaking his head no and smiling a secret smile into my ecstatic face. "Come on, Rebecca," he says, "let's go home."

When they meet in 1965 in Jackson, Mississippi, my parents are idealists, they are social activists, they are "movement folk." They believe in ideas, leaders, and the power of organized people working for change. They believe in justice and equality and freedom. My father is a liberal Jew who believes these abstractions can be realized through the swift, clean application of the Law. My mother believes they can be cultivated through the telling of stories, through the magic ability of words to redefine and create subjectivity. She herself is newly "Black." She and my father comprise an "interracial couple."

By the time they fall in love, my parents do not believe in the über-sanctity of family. They do not believe that blood must necessarily be thicker than water, because water is what they are to each other, and they will be together despite the objection of blood. In 1967, when my parents break all the rules and marry against laws that say they can't, they say that an individual should not be bound to the wishes of their family, race, state, or country. They say that love is the tie that binds, and not blood. In a photograph from their wedding day, they stand, brown and pale pink, inseparable, my mother's tiny five-foot-one-inch frame nestled birdlike within my father's protective embrace. Fearless, naive, breathtaking, they profess their shiny, outlaw love for all the world to see.

I am not a bastard, the product of a rape, the child of some white devil. I am a Movement Child. My parents tell me I can do anything I put my mind to, that I can be anything I want. They buy me Erector sets and building blocks, Tinkertoys and books, more and more books. Berenstain Bears, Dr. Seuss, Hans Christian Andersen. We are middle class. My mother puts a colorful patterned scarf on her head and throws parties for me in our backyard, under the carport, and beside the creek. She invites all of my friends over and watches over us as we roast hot dogs. She makes Kool-Aid and laughs when one of us kids does something cute or funny.

I am not tragic.

Late one night during my first year at Yale, a WASP-looking Jewish student strolls into my room through the fire-exit door. He is drunk, and twirling a Swiss Army knife between his nimble, tennis-champion fingers. "Are you really black and Jewish?" he asks, slurring his words, pitching forward in an old raggedy armchair my roommate has covered with an equally raggedy white sheet. "How can that be possible?"

Maybe it is his drunkenness, or perhaps he is actually trying to see me, but this boy squints at me then, peering at my nose, my eyes, my hair. I stare back at him for a few moments, eyes flashing with rage, and then take the red knife from his tanned and tapered fingers. As he clutches at the air above him, I hold it back and tell him in a voice I want him to be sure is black that I think he'd better go.

But after he leaves through the (still) unlocked exit door, I sit for quite a while in the dark.

Am I possible?

Black White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self

- Genres: Nonfiction

- hardcover: 288 pages

- Publisher: Riverhead Hardcover

- ISBN-10: 1573221694

- ISBN-13: 9781573221696