Excerpt

Excerpt

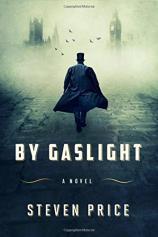

By Gaslight

Chapter One

He was the oldest son.

He wore his black moustaches long in the manner of an outlaw and his right thumb hooked at his hip where a Colt Navy should have hung. He was not yet forty but already his left knee went stiff in a damp cold from an exploding Confederate shell at Antietam. He had been sixteen then and the shrapnel had stood out from his knee like a knuckle of extra bone while the dirt heaved and sprayed around him. Since that day he had twice been thought killed and twice come upon his would-be killers like an avenging spectre. He had shot twenty-three men and one boy outlaws all and only the boy’s death did not trouble him. He entered banks with his head low, his eyebrows drawn close, his huge menacing hands empty as if fixed for strangling. When he lurched aboard crowded streetcars men instinctively pulled away and women followed him with their eyelashes, bonnets tipped low. He had not been at home more than a month at a stretch for five years now though he loved his wife and daughters, loved them with the fear a powerful man feels who is given to breaking things. He had long yellow teeth, a wide face, sunken eyes, pupils as dark as the twist of a man’s intestines.

So.

He loathed London. Its cobbled streets were filthy even to a man whose business was filth, who would take a saddle over a bed and huddle all night in a brothel’s privy with his Colt drawn until the right arse stumbled in. Here he had seen nothing green in a month that was not holly or a cut bough carted in from a countryside he could not imagine. On Christmas he had watched the poor swarm a man in daylight, all clutched rags and greed; on New Year’s he had seen a lady kick a watercress girl from the step of a carriage, then curse the child’s blood spotting her laces. A rot ate its way through London, a wretchedness older and more brutal than any he had known in Chicago.

He was not the law. No matter. In America there was not a thief who did not fear him. By his own measure he feared no man living and only one man dead and that man his father.

* * *

It was a bitter January and that father six months buried when he descended at last into Bermondsey in search of an old operative of his father’s, an old friend. Wading through the night’s fog, another man’s blood barnacling his knuckles, his own business in London nearly done.

He was dressed like a gentleman though he had lost his gloves and he clutched his walking stick in one fist like a cudgel. A stain spotted his cuffs that might have been soot or mud but was not either. He had been waiting for what passed for morning in this miserable winter and paused now in a narrow alley at the back of Snow Fields, opera hat collapsed in one hand, frost creaking in the timbers of the shopfronts, not sure it had come. Fog spilled over the cobblestones, foul and yellow and thick with coal fumes and a bitter stink that crusted the nostrils, scalded the back of the throat. That fog was everywhere, always, drifting through the streets and pulling apart low to the ground, a living thing. Some nights it gave off a low hiss, like steam escaping a valve.

Six weeks ago he had come to this city to interrogate a woman who last night after a long pursuit across Blackfriars Bridge had leaped the railing and vanished into the river. He thought of the darkness, the black water foaming outward, the slapping of the Yard sergeants’ boots on the granite setts. He could still feel the wet scrape of the bridge bollards against his wrists.

She had been living lawful in this city as if to pass for respectable and in this way absolve herself of a complicated life but as with anything it had not helped. She had been calling herself LeRoche but her real name was Reckitt and ten years earlier she had been an associate of the notorious cracksman and thief Edward Shade. That man Shade was the one he really hunted and until last night the Reckitt woman had been his one certain lead. She’d had small sharp teeth, long white fingers, a voice low and vicious and lovely.

The night faded, the streets began to fill. In the upper windows of the building across the street a pale sky glinted, reflected the watery silhouettes below, the passing shadows of the early horses hauling their waggons, the huddled cloth caps and woollens of the outsides perched on their sacks. The iron-shod wheels chittering and squeaking in the cold. He coughed and lit a cigar and smoked in silence, his small deep-set eyes predatory as any cutthroat’s.

After a time he ground the cigar under one heel and punched out his hat and put it on. He withdrew a revolver from his pocket and clicked it open and dialed through its chambers for something to do and when he could wait no longer he hitched up one shoulder and started across.

* * *

If asked he would say he had never met a dead nail didn’t want to go straight. He would say no man on the blob met his own shadow and did not flinch. He would run a hand along his unshaved jaw and glower down at whatever reporter swayed in front of him and mutter some unprintable blasphemy in flash dialect and then he would lean over and casually rip that page from the reporter’s ring-coil notebook. He would say lack of education is the beginning of the criminal underclass and both rights and laws are failing the country. A man is worth more than a horse any day though you would never guess it to see it. The cleverest jake he’d ever met was a sharper and the kindest jill a whore and the world takes all types. Only the soft-headed think a thing looks like what it is.

In truth he was about as square as a broken jaw but then he’d never met a cop any different so what was the problem and whose business was it anyway.

* * *

He did not go directly in but slipped instead down a side alley. Creatures stirred in the papered windows as he passed. The alley was a river of muck and he walked carefully. In openings in the wooden walls he glimpsed the small crouched shapes of children, all bones and knees, half dressed, their breath pluming out before them in the cold. They met his eyes boldly. The fog was thinner here, the stink more savage and bitter. He ducked under a gate to a narrow passage, descended a crooked wooden staircase, and entered a nondescript door on the left.

In the sudden stillness he could hear the slosh of the river, thickening in the runoffs under the boards. The walls creaked, like the hold of a ship.

That rooming house smelled of old meat, of water-rotted wood. The lined wallpaper was thick with a sooty grime any cinderman might scrape with a blade for half a shilling. He was careful not to touch the railing as he made his way upstairs. On the third floor he stepped out from the unlit stairwell and counted off five doors and at the sixth he stopped. Out of the cold now his bruised knuckles had begun to ache. He did not knock but jigged the handle softly and found it was not locked. He looked back the way he had come and he waited a moment and then he opened the door.

Mr. Porter? he called.

His voice sounded husky to his ears, scoured, the voice of a much older man.

Benjamin Porter? Hello?

As his eyes adjusted he could see a small desk in the gloom, a dresser, what passed for a scullery in a nook beyond the window. A sway-backed cot in one corner, the cheap mattress stuffed with wool flock bursting at one corner, the naked ticking cover neither waxed nor cleaned in some time. All this his eye took in as a force of habit. Then the bed groaned under the weight of something, someone, huddled in a blanket against the wall.

Ben?

Who’s that now?

It was a woman’s voice. She turned towards him, a grizzled Negro woman, her grey hair shorn very short and her face grooved and thickened. He did not know her. But then she blinked and tilted her face as if to see past his shoulder and he saw the long scar in the shape of a sickle running the length of her face.

Sally, he said softly.

A suspicion flickered in her eyes, burned there a moment. Billy?

He stepped cautiously forward.

You come on over here. Let me get a look at you. Little lantern-box Billy. Goodness.

No one’s called me that in a long time.

Well, shoot. Look at how you grown. Ain’t no one dare to.

He took off his hat, collapsed it uneasily before him. The air was dense with sweat and smoke and the fishy stench of unemptied chamber pots, making the walls that much closer, the ceiling that much lower. He felt big, awkward, all elbows.

I’m sorry to come round so early, he said. He was smiling a sad smile. She had grown so old.

Rats and molasses, she snorted. It ain’t so early as all that.

I was just in the city, thought I’d stop by. See how you’re keeping.

There were stacks of papers on the floor around the small desk, the rough chair with its fourth leg shorter than the others. He could see the date stamp from his Chicago office on several of the papers even from where he stood, he could see his father’s letterhead and the old familiar signature. The curtains though drawn were thin from long use and the room slowly belled with a grey light. The fireplace was dead, the ashes old, an ancient roasting jack suspended on a cord there. On the mantel a glazed pottery elephant, the paint flecking off its shanks. High in one corner a bubble in the plaster shifted and boiled up and he realized it was a cluster of beetles. He looked away. There was no lamp, only a single candle stub melted into the floor by the bed. He could see her more clearly now. Her hands were very dirty.

Where’s Ben? he asked.

Oh he would of wanted to seen you. He always did like you.

Did I miss him?

I guess you did.

He lifted his face. Then her meaning came clear.

Aw, now, she said. It all right.

When?

August. His heart give out on him. Just give right out.

I didn’t know.

Sure.

My father always spoke well of him.

She waved a gruff hand, her knuckles thick and scarred.

Why didn’t you write us? We would’ve helped with the expenses. You know it.

Well. You got your own sorrows.

I didn’t know if you got my letter, he said quietly. I mean if Ben got it. I sent it to your old address—

I got it.

Ben Porter. I always thought he was indestructible.

I reckon he thought so hisself.

He was surprised at the anger he felt. It seemed to him a generation was passing all as a whole from this earth. That night in Chicago, almost thirty years gone. The rain as it battered down over the waggon, the canvas clattering under its onslaught, the thick waxing cut of the wheels in the deep mud lanes of that city. He had been a boy and sat beside his father up front clutching the lantern box in the rain, struggling to keep it dry and alight as his father cursed under his breath and slapped the reins and peered out into the blackness. They were a group of eleven fugitive slaves led by the furious John Brown and they had hidden for days in his father’s house. Each would be loaded like cargo into a boxcar and sent north to Canada. They had journeyed for eight weeks on stolen horses over the winter plains and had lost one man in the going. He had known Benjamin and Sally and two others also but the rest were only bundles of suffering, big men gone thin in the arms from the long trek, women with sallow faces and bloodshot eyes. Their waggon had lurched to a halt in a thick pool of muck just two miles shy of the rail yards and he remembered Ben Porter’s strong frame as he leaned into the back corner, squatted, hefted the waggon clear of its pit, the rain running in ropes over his arms, his powerful legs, and the strange low sound of the women singing in the streaming dark.

Sally was watching him with a peculiar expression on her face. You goin to want some tea, she said.

He looked at her modest surroundings. He nodded. Thank you. Tea would be just fine. He made as if to help her but she shooed him down.

I ain’t so old as all that. I can still walk on these old hoofs.

She got heavily to her feet, gripping the edge of one bedpost and leaning into it with her twisted forearm, and then she shuffled over to the fireplace. She broke a splint from a near-toothless comb of parlour matches and drew it through a fold of sandpaper. He heard a rasp, smelled a grim whiff of phosphorous, and then she was lighting a twist of paper, bending over the iron grate, the low rack of packing wood stacked there. The bricks he saw were charred as if she had failed to put out whatever fire had burned there last.

How you take it? she asked.

Black.

Well I see you got you lumps already. She gestured to his swollen knuckles.

He smiled.

She was wrestling the cast-iron kettle over the grating. You moved, he said delicately. He did not want to embarrass her. I didn’t have your new address.

She turned back to look at him. One eye scrunched shut, her spine humped and malformed under her nightgown. You a detective ain’t you?

Maybe not a very good one. What can I do to help?

Aw, it boil in just a minute. Ain’t nothin to be done.

I didn’t mean with the tea.

I know what you meant.

He nodded.

It ain’t much to look at but it keep me out of the soup. An I got my old arms and legs still workin. I ain’t like to complain.

He had leaned his walking stick against the brickwork under the mantel and he watched Sally run her rough hands over the silver griffin’s claw that crested its tip. Over and over, as if to buff it smooth. When the water had boiled she turned back and poured it out and let it steep and shuffled over to the scullery and upended one fine white china teacup.

You say you been here workin? she called out to him.

That’s right.

I allowed maybe you been lookin for that murderer we been readin bout. The one from Leicester.

He shrugged a heavy shoulder. He doubted she was doing any reading at all, given her eyes. I’ve been tailing a grifter, she had a string of bad luck in Philadelphia. Ben knew her.

Sure.

I caught up with her last night but she jumped into the river. I’d guess she’ll wash up in a day or two. I told Shore I was here if he needs me. At least as long as the Agency can spare me.

Who’s that now. Inspector Shore?

Chief Inspector Shore.

She snorted. Chief Inspector? That Shore ain’t no kind of nothin.

Well. He’s a friend.

He’s a scoundrel.

He frowned uneasily. I’m surprised Ben talked about him, he said slowly.

Wasn’t a secret between us, not in sixty-two years. Specially not to do with no John Shore. Sally carried to him an unsteady cup of tea, leaned in close, gave him a long sad smile as if to make some darker point. You got youself a fine heart, Billy. It just don’t always know the cut of a man’s cloth.

She sat back on her bed. She had not poured herself a cup and he saw this with some discomfort. She looked abruptly up at him and said, How long you say you been here? Ain’t you best be gettin on home?

Well.

You got you wife to think about.

Margaret. Yes. And the girls.

Ain’t right, bein apart like that.

No.

Ain’t natural.

Well.

You goin to drink that or leave it for the rats?

He took a sip. The delicate bone cup in his big hand.

She nodded to herself. Yes sir. A fine heart.

Not so fine, he said. I’m too good a hater for much. He set his hat on his head, got slowly to his feet. Like my father was, he added.

She regarded him from the wet creases of her eyes. My Mister Porter always tellin me, you got to shoe a horse, best not ask its permission.

I beg your pardon?

You goin to leave without sayin what you come for?

He was standing between the chair and the door. No, he said. Well. I hate to trouble you.

She folded her hands at her stomach, leaned back thin in her grey bedclothes. Trouble, she said, turning the word over in her mouth. You know, I goin to be eighty-three years old this year. Ain’t no one left from my life who isn’t dead already. Ever morning I wake up surprised to be seein it at all. But one thing I am sure of is next time you over this side of the ocean I like to be dead and buried as anythin. Aw, now, dyin is just a thing what happen to folk, it ain’t so bad. But you got somethin to ask of me, you best to ask it.

He regarded her a long moment.

Go on. Out with it.

He shook his head. I don’t know how much Ben talked to you about his work. About what he did for my father.

I read you letter. If you come wantin them old papers they all still there at his desk. You welcome to them.

Yes. Well. I’ll need to take those.

But that ain’t it.

He cleared his throat. After my father passed I found a file in his private safe. Hundreds of documents, receipts, reports. There was a note attached to the cover with Ben’s name on it, and several numbers, and a date. He withdrew from his inside pocket a folded envelope, opened the complicated flap, slid out a sheet of drafting paper. He handed it across to her. She held the paper but did not read it.

Ben’s name goin to be in a lot of them old files.

He nodded. The name on this file was Shade. Edward Shade.

She frowned.

It was in my father’s home safe. I thought maybe Ben could help me with it.

A brougham clattered past in the street below.

Sally? he said.

Edward Shade. Shoot.

You’ve heard of him?

Ain’t never stopped hearin bout him. She cast her face towards the weak light coming through the window. You father had Ben huntin that Shade over here for years. Never found nothin on him, not in ten years. She looked disgusted. Everyone you ask got they own version of Edward Shade, Billy. I won’t pretend what I heard is the true.

I’d like to hear it.

It’s a strange story, now.

Tell me.

She crushed her eyes shut, as if they pained her. Nodded. This were some years after the war, she said. Sixty-seven, sixty-eight. Shade or someone callin hisself Shade done a series of thefts in New York an Baltimore. Private houses, big houses. A senator’s residence is the one I heard about. Stole paintings, sculptures, suchlike. All them items he mailed to you father’s home address in Chicago, along with a letter claimin responsibility an namin the rightful owner. Who was Edward Shade? No one knew. No one ever seen him. It was just a name in a letter far as anyone known. First packages come through, you father he return them on the quiet to they owners an get a heapful of gratitude in turn. But when it keep on happenin, some folk they start to ask questions. All of it lookin mighty suspicious, month after month. Like he was orchestratin the affair to make the Agency look more efficient. Some daily in New York published a piece all about it, kept it goin for weeks. That newspaper was mighty rough on the Agency. It embarrassed you father something awful, it did.

I remember something about that.

Sure. But what else was he goin to do? They was stolen items, ain’t no choice for a man like you father but to return them rightfully back.

Yes.

An then the case broke an the whole affair got cleaned up. Turned out Shade weren’t no one after all. It were a ring of bad folk had some grudge against you father. They was lookin for some leverage an if that weren’t possible they was hopin to embarrass the Agency out of its credibility. Edward Shade, that were just a name they made up.

But he had Ben hunting Shade for years after.

Right up until the end. You father had his notions.

None of that was in the file.

Sally nodded. Worst way to keep a secret is to write it down.

Ben ever mention a Charlotte Reckitt?

Sally touched two fingers to her lips, studied him. Reckitt?

Charlotte Reckitt. In the file on Shade there was a photograph of her. Her measurements were on the back in Ben’s handwriting. There was a transcript attached, an interview between Ben and Reckitt from seventy-nine. In it he asks her about some nail she worked with, someone she couldn’t remember. Ben claimed there were stories about them in the flash houses in Chicago but she didn’t know what he was talking about or claimed she didn’t. He left it alone eventually. Diamond heists, bank heists, forgeries circulating through France and the Netherlands, that sort of thing. According to my father’s notes, he was certain this nail was Shade. In September I sent out a cable here and to Paris and to our offices in the west with a description of Charlotte Reckitt. Shore got back to me in November, said she was here, in London. Where my father had Ben on the payroll.

Billy.

Before he died, the last time I saw him, he looked me in the eye and he called me Edward.

Billy.

It was almost the last thing he said to me.

She looked saddened. My Mister Porter got mighty confused hisself, at the end, she said. You know I loved you father. You know my Mister Porter an me we owe him our whole lives. But that Edward Shade, now? You take them papers, go on. You read them an you see. It ain’t like you father made it out to be. He were obsessed with it. Shade were like a sickness with him.

He studied her in the gloom. I found her, Sally. The woman I was following last night, the woman who took her life. It was Charlotte Reckitt.

Shoot.

I talked to her before she jumped, I asked her about Shade. She knew him.

She told you that?

He was silent a long moment and then he said, quietly, Not in so many words.

Sally opened her hands. Aw, Billy, she said. If you huntin the breath in a man, what is it you huntin?

He said nothing.

My Mister Porter used to say, Ever day you wake up you got to ask youself what is it you huntin for.

Okay.

What is it you huntin for?

He walked to the window and stared out through the frost and soot on the pane at the crooked rooftops of the riverside warehouses feeling her eyes on him. The sound of her breathing in the darkness there. What are you saying? That Shade didn’t exist?

She shook her head. There ain’t no catchin a ghost, Billy.

* * *

When does a life begin its decline.

He thought of the Porters as they had once been and still were in his mind’s eye. The glistening rib cage of the one in the orange lantern light and the rain, wool-spun shirt plastered to his skin, his shoulders hoisting that cart up out of the muck. The low plaintive song of the other as she kneeled coatless in the waters. He thought of the weeks he had tailed Charlotte Reckitt from her terrace house in Hampstead to the galleries in Piccadilly, trailed her languidly down to the passenger steamers on the Thames, watched in gaslight the curtained windows of her house. Hoping for a glimpse of Edward Shade. She was a small woman with liquid eyes and black hair and he thought suddenly of how she had regarded him from the steps of that theatre in St. Martin’s Lane, one gloved wrist bent back. The fear in her eyes. Her small hands. She had leaped a railing into a freezing river and they would find her body in the morning or the day after.

So.

He would be thirty-nine years old this year and he was already famous and already lonely. In Chicago his wife was dying from a tumour the size of a quarter knuckled behind her right eye though neither he nor she knew it yet. It would be another ten years before it killed her. He had held the rope as his father’s casket went in and turned the first shovel of earth over the grave. That scrape of dirt would echo in him always. Whether he lived to eighty or no, the greater part of his life lay behind him.

When does a life begin its decline? He stared up at the red sky now and thought of the Atlantic crossing and then of his home. The fog thinning around him, the passersby in their ghostly shapes. Then he went down to Tooley Street to catch the rail line back to his hotel.

His name. Yes, that.

His name was William Pinkerton.

Copyright © 2016 by Steven Price

By Gaslight

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical Mystery, Historical Thriller, Mystery, Thriller

- hardcover: 752 pages

- Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- ISBN-10: 0374160538

- ISBN-13: 9780374160531