Excerpt

Excerpt

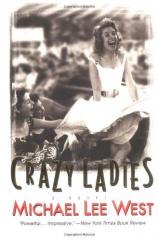

Crazy Ladies

Miss Gussi

1932

My baby had the spring colic, and I remember just as plain as day, there was nothing I could do to calm her. All morning I walked up and down the length of the porch, jiggling her in my arms, watching Charlie plow the garden. The air around him seemed dust-charged, fine particles wafting in the March sun.

"Look at your papa," I'd say, but Dorothy just wailed. Charlie wasn't a farmer. He was a teller at Citizens' Bank, and he was proud to bring home fourteen dollars every week. Before the Depression, he'd had hopes of advancing to cashier. I always expected the bank to close. In spite of his good job, I was of a mind to stuff our money into a mattress. Stick it in a jar and bury it next to the climbing roses. Charlie just shook his head when I talked like that. But I knew what I knew. Mr. Wentworth, who owned the bank, gave Charlie and the other tellers thick stacks of one-dollar bills; then he'd cover the stacks with fifties and hundreds. People would come to the bank, see all the money, and go home satisfied.

I'd been hankering to start me a garden early. I thought it would ease my mind from worrying about the baby, worrying about the awful things going on. There is so much good in a garden, if you don't count what happened to Adam and Eve. When I was a girl, my favorite hymn was "In the Garden." I would sing at the top of my lungs, I come to the garden alone, while the dew is still on the roses. I pictured me a mess of butter beans and squash, not roses. I pictured squatting between the long green rows, me working in the sun, Dorothy sleeping in a wicker basket.

We lived on the edge of town, but we had no close neighbors. Before Dorothy was born, I'd watch Charlie shoot cracked milk bottles in the backyard. I was a better shot than him, on account of my brothers learning me, but I didn't have the heart to tell him. I let him think he showed me everything I knew. You have to coddle menfolks on account of their pride.

The Depression had made us all prouder. A man on the radio said too much prosperity ruined the fiber of the people. I wondered why he'd say a thing like that. When I looked around town, all I saw was poverty and slow living, Tennessee ways. I didn't know about the big cities, but there were tarpaper shacks beside the railroad in Crystal Falls. Most of the men held signs, WILL WORK FOR FOOD. They were skinny as chickens. Hoovervilles, the papers called those shacks. Charlie said he didn't see how President Hoover would be re-elected in November. I didn't know what to think.

I had plenty on my mind. My nerves were laid wide open from Dorothy's high-pitched cries, which I could not soothe and could not help but take personal. She was my first baby. I was eighteen years old, a bride of one year, the youngest child from a family of seven. So I just didn't know what to do. There had never been babies for me to help Mama raise. To make things worse, I could not seem to turn away from the terrible news on the radio. It was the middle of March, and the body of the Lindbergh baby had just been found. The Philco radio was paid for, and it had a glass dial like a single eye. From the porch, I listened to the radio and watched Charlie turn the soil. I held my Dorothy and offered her my breast, which only made her cry harder. I moved the rocker into a patch of sunlight and rocked her back and forth.

I couldn't get the handsome Lindberghs out of my mind.

That was also the year a series of murders shocked Crystal Falls. The victims, four total, were all young women. They had been stabbed, but I'd heard that the newspaper hadn't reported everything. I didn't want to know. It was such a large crime, in such a small town, that people were cowed by the news. Women whispered among themselves, but mostly they didn't like to think about it. It didn't seem real. Instead we hovered around our radios for news of the Lindberghs. It was a relief when music came on, playing over the static. I always liked "Star Dust"-Sometimes I wonder why I spend the lonely nights/ Dreaming of a song? Saturday evenings me and Charlie sat in the dark and watched the glowing dial while we listened to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM.

It was late afternoon when Dorothy, all red-faced, fell asleep chewing her fingers. I set her in the bassinet, rolled it into the kitchen, and looked out the window. Charlie was moving his plow into the barn. The garden was long and narrow. It was almost in the center of the backyard. Most every place else was full of limestone-the rocks jutted out like broken bones. One end of the garden, the east side, was shaded by a huge oak tree. Charlie said that tree had been there forever. Beyond the tree was the old graveyard, past the barn and the barbwire fence. I didn't cotton to living next to it, but I held my tongue. It was Charlie's land. The old homeplace, which I didn't have a memory of, had burned in 1902. Over the years, some of the markers...

Crazy Ladies

- paperback: 416 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060977744

- ISBN-13: 9780060977740