Excerpt

Excerpt

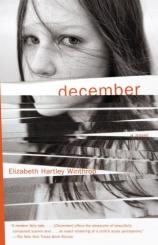

December

One

Saturday

Wilson’s got his arm deep in the twisted mess of wires, pipes, and tubing that festers there beneath his truck’s dented hood like the intestines of some living thing. He gropes at the undersides of things, trying to find whatever leaking crack it is that’s caused him now to fail inspection twice. That and the broken hinge of the driver’s seat, which he keeps upright by stacking milk crates behind it.

“Damn truck,” he mutters. “Goddamn.” He says it though he loves this truck, he wouldn’t ever trade it in. It keeps him busy on the weekends; it’s a project, a chore.

Today is Wilson’s birthday. He looks younger than his forty-two years, and in many ways he feels it. He feels the same as he always has, all his life, same as he did as a kid stalking through the woods with a BB gun or a young man drunk at a keg party, and so sometimes he doesn’t recognize the city businessman he’s become, with a weekend house in the country, a wife, a child who breaks his heart. He’d always thought by the time he got to somewhere around forty-two he’d be ready to accept stiffening joints and graying hair, wrinkles and cholesterol pills, but when these things apply to him he feels as if there’s been some mistake; he’s not quite ready for them yet.

He pulls his arm out from under the truck’s hood and starts to wipe the grease from his hand onto the rag he’s taken from the bag of them in the hall closet: old clothing ripped into neat squares. He stares absently at the truck’s engine as he rubs the rag over his fingers one by one, then he shuts the hood. He’ll have to take the thing in to the shop, he thinks; he’s no mechanic. A breeze chills him, and he looks at the sky. The clouds are low and rolling. Fall leaves ride the air, and he imagines gulls at the nearby shore coasting the wind. Late autumn always fills him with something like fear, or dread, or sadness; he’s never sure how to label the feeling. It’s an awareness of the inevitable impending dark, barren cold of winter, which when it comes is fine, he knows, and eventually ends. Still, he shudders.

Firewood, he thinks. He should chop some firewood. He’s bought a new rack to store it on outside this winter, with a tarp attached to keep it dry; he assembled it last weekend, and now it needs filling. He should bring some wood inside, too; it’s getting cold enough for a fire, and Isabelle loves a fire. She’ll sit in front of one for hours, reading, or drawing, or staring at the flames, rotating her body when one side gets too hot. Like a chicken on a spit, he once said, which made her laugh.

He walks to the garage for an ax. He tosses the dirty rag he’s holding into the trash can, which is nearly overflowing with cardboard, Styrofoam, wood scraps, newspapers, empty paint cans and oil bottles, and other rags like this one. He stares at the newest rag and tilts his head in recognition. The rag is flannel, printed with purple alligators. It’s from a nightgown he brought back years ago for Isabelle, from a business trip to where? Spain, or maybe Portugal that time; he can’t remember. But he does remember buying it, calling Ruth back in the States to make sure that he bought the right size, and the right size slippers to match.

He takes the rag from the trash can and holds it in his hand. He considers folding it up, tucking it away somewhere, but then he sees no point in that. He hesitates a second more, then tosses it back into the can, lifts his ax, and goes outside.

...

Ruth stands over the kitchen sink peeling carrots. “I thought I’d make split pea,” she says. “A huge vat of it that we can keep frozen and warm up, you know, on those Friday nights when we get here and it’s late and cold and the furnace is out or the pipes are frozen. I feel like that happens more and more each winter, but wouldn’t it be nice to have a warm bowl of soup? That and a fire, if your father ever gets around to chopping wood.” She puts the last peeled carrot down onto the pile of them stacked on the cutting board and watches the skin spin down the drain as she runs the disposal.

“You know,” she says, chopping the carrots into coins, “your uncle called this morning. He’s convinced he’s under surveillance. He’s being buzzed by black helicopters. He’s counted thirty-six since yesterday.” She wipes the hair from her forehead with the back of her wrist. “And,” she says, “he thinks Ronna’s mind is being poisoned.” Ruth looks up. “Because she uses aspartame, not sugar.” She pushes the carrot coins to the side of the cutting board and reaches for an onion.

The kitchen opens onto the family room, the rooms themselves separated only by the wide counter where Ruth stands. She looks up over the counter and into the other room, where her daughter sits at the table, her head bent low over her sketchbook, a pencil clutched firmly in her hand. She looks stern with concentration, and Ruth can tell by the whiteness of her fingertips that she is pressing the pencil hard against the page. She is framed by the picture window, and her silhouette is dark against the sky behind her, its steely canvas broken only by the jagged limbs of the apple tree, Ruth’s favorite. Bare long before the other trees this fall, the apple tree is dying, Ruth knows. Wilson wanted to cut it down, but she wouldn’t let him.

“It’s dead, Ruth,” he’d said.

“It’s not dead,” she’d said. “It’s dying. Let’s just let it die.”

The winter will kill it, she suspects. It’s meant to be a bad one.

“Do you know what my mother said to me on her deathbed?” Ruth asks, flaking the onion’s skin away. “I asked her, I said, ‘Mother, what am I going to do about Jimmy?’ And she looked at me, and she smiled, and she said, ‘Ruthie, I don’t know, but he is your problem now.’ And, my God, words have never been truer.” She picks the knife back up and holds it above the onion, then she pauses. “I’m just not quite sure what I’m supposed to do.” She lowers the knife onto the onion. “What do I say about thirty-six black helicopters, for instance? Do I say I see them, too? That everyone does? Or do I tell him he’s delusional?”

Ruth steps back from the onion to dry her eyes. Isabelle has not looked up. A large pot of water on the stove has finally come to a boil, and Ruth pours several bags of split peas in. “There,” she says. “That should last us for a couple months at least. Maybe even all winter. Though I’d like to make lentil, too, at some point.” She turns back to the cutting board. Her daughter hunches over her sketchbook, very still except for the slow and deliberate movements of her drawing hand.

“I’d like to see what you’re drawing, Isabelle,” Ruth says. “When you’re finished, if you want to show me.”

Her daughter says nothing, though Ruth didn’t expect an answer. Isabelle hasn’t spoken for nine months now. She has been to countless doctors and psychiatrists, but nothing seems to help, to penetrate the silence. Ruth is sure that she is somehow responsible. There are images that haunt and tease: Isabelle at two, sitting alone on the edge of the sandbox in the same blue overalls every day, watching as the other children play; Isabelle at four, sitting small among her preschool classmates, glancing often at Ruth with her book in the corner to make sure she hasn’t left her there alone; Isabelle in tears on her first day of kindergarten when finally Ruth arrived to pick her up, ten minutes late. Isabelle had taken literally her teacher’s joking threat to turn the stragglers into chicken soup, and she had nightmares for months. Of all days, on that day, Ruth should have been on time. And maybe she shouldn’t have stayed with her daughter at preschool, the only parent, until April, when Isabelle was finally ready to let her go. Maybe she should have gotten into the sandbox with her daughter and helped her to make friends instead of allowing her to sit as a spectator until she was comfortable. She’s read countless books on parenting, trying to figure out just where she went wrong, and how she can make it right. Each book tells her something different: she should discipline, she should tolerate, she should encourage independence, she should allow for dependence—and each book points to a mistake. Where she should have tolerated, she disciplined instead; where she should have disciplined, she didn’t.

She lifts the cutting knife and begins to chop the second onion. She hears the back door whine open and waits to hear it close; it doesn’t. “Shut the door!” she yells. “You’re letting out the heat!”

Wilson appears in the kitchen door with a bundle of firewood in his arms. “What are you making?” he asks.

“Split pea. Could you please close the door behind you when you come inside?”

“My arms are full. And I’m going right back out,” he says, passing through the kitchen into the family room. “I’m going to bring another load in.”

“Yes, well, in the meantime I can already feel the draft.”

Ruth sets her knife down and goes to shut the door herself. When she comes back into the kitchen, she sees Wilson crouched at the hearth, building a fire. “It’s fire season, Belle,” he’s saying. “I thought you might like a fire. Doesn’t that sound good?”

Isabelle doesn’t look up from her drawing. Ruth watches as Wilson balls up newspaper to set beneath the logs. “Don’t forget to open the flue,” she says.

Wilson says nothing. When the wood catches flame and a steady fire is going, he stands up and takes a step backward.

“It’s nice to have a fire,” Ruth says. “Thank you.”

Wilson brushes his hands off on his thighs. “I’m going to bring a few more loads in,” he says.

“Why don’t you sit down?” Ruth says. “Why don’t you relax, read the paper or something? It’s the weekend. It’s your birthday. We don’t need more wood right now.”

“Might as well, while I’m at it,” Wilson says. “And I need to get the logs I just cut under the tarp before it starts to rain.” He looks out the window. “It looks like it just might rain.”

“Maybe snow,” Ruth says. “Wouldn’t that be exciting? Maybe if it snows you could even sled tomorrow, Isabelle.”

“Or we could build a snow fort. Remember that one last year?” Wilson says, going over to stand by his daughter’s side. Isabelle slides her hand over the drawing. Wilson’s face goes slack. “Sorry,” he says quickly. “I’m not looking.” He ruffles his daughter’s hair and hurries through the kitchen for the door.

“Wil,” Ruth calls after him. He turns in the kitchen doorway, his face red, whether with cold from outside or heat from the fire or something else Ruth can’t be sure. “I made reservations at Luigi’s. For seven o’clock.”

Wilson nods and smiles stiffly. “Great,” he says. “Sounds good.”

...

If it does anything, it will snow. Even with the gloves he wears for handling firewood, Wilson’s fingers have gone numb. He throws the last of the wood onto the rack and covers the pile with the tarp. He straightens up, pauses to catch his breath. Across the street and down aways, he can make out a moving truck beeping its way backward down the driveway toward Mr. Sullivan’s old house. He sniffs, takes the ax from where he’s rested it against the side of the house, and brings it into the garage where it belongs.

The garage is a mess. There are boxes of who knows what stacked ceiling high and piles of other clutter: garden hose, sprinkler, paint cans, drop cloths, bicycles and tire pumps, croquet set, deflated basketball, old moldy hammock. There is no room for a car in here, though there could be room for two. He should make room. He should clean this garage out. If it’s going to be a bad winter, truly, his truck might appreciate the shelter of a garage. His truck would probably be in a lot better shape if it had wintered in garages all its life. This is something he should do, before the snow, before it’s too late, right now.

He decides to start with the clutter, since he can’t get to the boxes until the clutter is cleared away. He pulls garbage bags filled with clothes for Goodwill off an old loveseat and brings them outside, then he pushes the loveseat itself out into the driveway. He brings outside old paintings leaned up against the wall; these are mildewed, and wisps of a spiderweb stretch across the corner of a frame. He drags out the hammock, the croquet set, several pairs of rusted cross-country skis, bent poles, an old sled. Behind the box the birdhouse came in, he finds a familiar box that he’d forgotten. It contains a zip cord to be stretched between two trees and a swing to ride between them. He’d bought it for Isabelle last year for Christmas, but somehow it hadn’t made it under the tree.

He opens the box and unpacks the wire and the swing. The set comes with hooks to drill into the trees and, according to the directions, setup looks easy enough. Wilson steps outside the garage and surveys the edge of the woods behind their house for suitable trees to stretch the cord between. There are two that look solid enough, the space between them clear of other trees and long enough for a decent ride. He takes the power drill from where it sits on the shelf, a tape measure, and the box with the zip cord out to the trees. He measures exactly seven feet up from the ground and makes a mark on each tree with one of the hooks; seven feet is high enough that Isabelle will be able to dangle without needing to lift up her legs and low enough that if she were to fall she’d be okay. He goes to drill the hook holes, but the power drill is dead. He takes it back to the garage to charge it, but this zip cord is something he wants to set up now, not later, so he goes back to the trees with a large screw and screwdriver and starts to drill the holes by hand. The wood is hard, and his fingers are numb, but slowly, stubbornly, he twists the screw around, around, around.

“Wilson!” he hears Ruth’s voice calling from the driveway. He looks toward her and blinks, unsure of how long he’s even been standing at this tree. Isabelle is standing at her mother’s side. “What are you doing?” Ruth says, gesturing at all the junk he’s left out in the driveway.

Wilson sets his tools down and walks toward his wife and daughter. “I was cleaning out the garage,” he says.

Ruth looks past him toward the tree he’s been working on. “Looks to me like you’ve made a mess of the driveway and are busy communing with a tree.”

“I found a zip cord. You know, one of those things you ride between the trees? I thought I’d set it up for Isabelle.”

“I see.”

“And the power drill is dead.”

“Right. Well, we’re going to the grocery store. We shouldn’t be more than an hour, but I’ve left the split pea simmering, so could you go in and give it a stir once or twice?”

She opens the door to their station wagon and gets in. Isabelle gets in on the other side, and they drive away. Exhaust lingers in the cold air even after Wilson can no longer hear the car’s engine. He breathes on his hands to warm them, and turns back to the tree.

“I spoke with Dr. Kleiner after your appointment yesterday,” Ruth says. She glances over at her daughter in the passenger seat. Isabelle stares out the side window—or rather at it, Ruth thinks; she can’t see through it for the fog gathered on the glass. “He says he’s not sure he’s the right doctor for you, and he thinks we should find someone else.” She turns the defrost on high, keeping her eyes on the road ahead. It’s a narrow, tree-lined road with blind curves. Ruth drives fast. “He says it takes two to make progress. You can’t draw water from stone.” Ruth sighs and lowers the defrost. They come around a bend in the road and up suddenly on the tail of another car. Ruth brakes and frowns. “Fucking asshole,” she mutters.

She’s quiet for a minute. “Look, Isabelle,” she says. “If you don’t want to speak to me, and you don’t want to speak to your father, fine, but please, please try to cooperate with the doctors. Dr. Kleiner was what, the fourth? They just want to help you. I want to help you. Your father wants to help you. We all want to help you. We love you. Don’t you want to get better? Don’t you want to get to the bottom of all this shit?” She looks at her daughter hopefully. Isabelle sits like stone.

The two ride in silence for the rest of the drive. Ruth grips the steering wheel hard. She is angry at these doctors. All of them, it seems, have given up on Isabelle after little more than a month, each sending her on to another doctor who after a month will send her on to someone else. Ruth tries to explain to them that Isabelle is shy, that it takes her time to get comfortable, that if they only gave her a little bit longer she might warm up to them, might give them her trust. Dr. Kleiner had used the phrase “lost cause.” The recollection makes Ruth fume. That was the only diagnosis he could come up with, since no one can seem to find anything “wrong”: it’s not Asperger’s, it’s not autism, it’s not anything that can be tested for and named. As far as Ruth and Wilson know, there’s been nothing specific to catalyze it, no trauma or abuse. Lost cause. She pulls the car into the grocery store parking lot and parks with a lurch. Her daughter is no lost cause. Ruth will not give up. She looks at Isabelle. “We’re going to beat this thing,” she says. “Now let’s go shopping.”

Wilson has gotten about a half inch into the wood when he finally accepts the futility of trying to bore these holes by hand. He goes into the garage to test the power drill, but it’s mustered enough juice for only a feeble whining spin. He squints at the label; it takes two to three hours to fully charge. And it is not for dental use, thank you. He sets it back in the charger and surveys the garage and the things he’s dragged outside. He’s lost enthusiasm for this project; he knows from times past that cleaning out a space just makes room for more clutter in the end. And what does it matter about the truck? One more winter won’t kill it, and if it does, well, the thing’s pretty much had it anyway. What he should do, Wilson thinks, is get himself a sports car or a motorcycle. He’s a middle-aged businessman, after all, and don’t middle-aged businessmen do these kinds of things? Though he doesn’t know quite what he’d do with a sports car or a motorcycle. He wouldn’t dare tinker with either of them as he does his truck, and it’s the tinkering he likes best.

A gust of wind blows dry leaves and sharp air into the garage. Wilson shivers. Already it’s starting to get dark. Wilson looks at his watch: three thirty. Ruth and Isabelle should be back soon from the grocery store. Wilson remembers the soup.

Ruth hands Isabelle the grocery list. This is always how it goes: Ruth pushes the cart up one aisle then the next while Isabelle runs through the store finding all the items on the list and brings them back to the cart, where she arranges them with scientific precision; their cart is always neatly packed. Isabelle has retrieved almost every item on the list and the cart is nearly full when Ruth reminds her to get ingredients for cake. “I didn’t write them on the list because I didn’t want your father to see. But we need to make a cake to bring to the restaurant as soon as we get home. Or you need to. We always said when you were eleven you could do the whole thing yourself, didn’t we?” She thinks, hopes, she catches the trace of a smile on her daughter’s face. Isabelle’s specialty, learned from Ruth, is devil’s food cake with vanilla icing, raspberry jam between the two layers. Isabelle knows where to find what she’ll need; she leaves Ruth in the produce aisle to get them.

Ruth pushes the cart to the side of the aisle and out of the way of the other shoppers while she waits for Isabelle to return. She looks at the neatly stacked groceries in the cart in front of her and tries to remember when her daughter developed this grocery store habit. Three years ago? Four? Ruth wonders if she should have taken such perfectionism as a sign that something wasn’t right. If she had, then maybe things wouldn’t have to gotten to this point. And even if she hadn’t taken that as a warning sign, surely she should have worried more when her daughter insisted on moving her mattress into the middle of her bedroom and taking the frame away to make things “safe.” And certainly she should have thought twice when, at eight, Isabelle cultivated the ability to speak backward. Too many times these thoughts have crossed her mind, and she is getting tired of them.

She wonders what would happen if she rearranged a box or two. She wonders if Isabelle would notice. Looking around her first to make sure her daughter is nowhere in sight, Ruth puts the Triscuits where the raisin bran had been and the raisin bran in the Triscuits’ spot. Just a subtle change. The two boxes are about the same size, so the overall arrangement of things hasn’t been disrupted.

Isabelle returns with a box of devil’s food cake mix, the icing, and the jam. They already have the eggs and oil at home. She puts the icing and the jam with the other jars—peanut butter, pickles, and pasta sauce—in the child seat, but then she pauses when she goes to put the box of cake mix in among the other boxes down below. She stares into the cart, then slowly, deliberately, puts the Triscuits and raisin bran back into their original positions. She finds a spot for the cake mix and looks Ruth hard in the eye. Ruth feels herself blushing. “Isabelle,” she says. She wonders if she should make up an excuse: she was just reading the backs of all the boxes as she waited and must have put them away wrong, she thought the yellow of the Triscuits box would look better beside the red of the Cheez-Its box than the purple of the raisin bran did. “I’m sorry,” she says, but Isabelle is already headed in the direction of the check-out lane.

December

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0307388573

- ISBN-13: 9780307388575