Excerpt

Excerpt

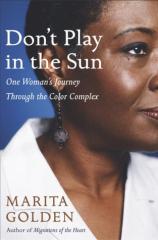

Don't Play In the Sun: One Woman's Journey Through the Color Complex

Scenes from the Color Complex: (My Own)

Ah just couldn't see mahself married to no black man. It's too many black folks already. We ought to lighten up the race.

--FROM THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING GOD BY ZORA NEALE HURSTONThis society measures the progress for the Negro by how fast he can turn White.

--JAMES BALDWIN

I am ten, standing before the gilt-framed mirror over the mahogany cabinet where the silver and good china are stored. It is seven-thirty and my mother, my father, and I have finished dinner. I have washed the dishes. My parents are upstairs in their bedroom. I stand before the mirror as I do almost every night when I have the dining room to myself. My head is draped in four long silk scarves that belong to my mother. Scarves held in place with a bobby pin at the top of my head. Scarves that are a seductive color-drenched kaleidoscope whose silk fabric kisses my brown cheeks as I imagine a White girl's hair must brush her skin--with the most awesome feeling of affirmation, beauty, and power. Standing before that mirror I am Snow White. I am Cinderella. My short, has-to-be-straightened-with-a-hot-comb hair has disappeared. My hands, like hungry butterflies, are lost in the soft, imaginary tendrils that I see with a contented, dangerous stranger's eyes. With those eyes I convince myself that I can actually see the metamorphosis of the scarves into shoulder-length and even sometimes blond hair that frames my chubby brown face and that, at last, makes me real.

My mother, in a rare mood of satisfaction with my father, tells me, "Your daddy is black, but he sure is handsome."

One summer afternoon when I am playing outside, racing the boys on our street to see who can reach the end of the block first (I do), my mother comes onto the porch and as I speed past shouts out to me, "Come on in the house--it's too hot to be playing out here. I've told you don't play in the sun. You're going to have to get a light-skinned husband for the sake of your children as it is."

In fifth grade we learn how to square dance and are assigned partners. My partner is Gregory, an olive-skinned White boy with raven-dark hair. In the center of the classroom, boys and girls face each other, giggly and jittery with anticipation. We nervously wait for the square dance music to begin. Gregory stands with a hand on his narrow blue-jeaned hips. His thin lips are curled in disgust at the sight of me. I am not the partner he wanted. When we square dance, we will have to touch. When we square dance, we will have to be close. I had liked Gregory until this moment, when his eyes calmly, purposely erase me and I stand squirming in my new dress worn just for this occasion. I glance down the aisle of boys, wondering who else could be my partner. When Miss Willis places the needle onto the record and the classroom fills with the sound of raucous, cheerful fiddle music, Gregory and I tentatively reach for each other's hands. We are reaching for each other across a centuries-old chasm of history and hate and hope and fear. When he touches my fingers Gregory jumps back and ostentatiously wipes his hands on the side of his jeans, as though now his hand will never be clean again, and walks back to his desk and sits down. I stand partnerless, exposed as what I saw in Gregory's eyes--not a girl, not his classmate, but a black and ugly and dirty thing.

Gregory didn't want to touch me, and there were boys I was afraid to touch. Boys like Russell in junior high school. Russell of the light "pretty brown" skin, and the "good" curly hair. Russell, whom all the girls wanted and who, on the occasions his glance slid over my face (quickly, never long enough to give me hope), made me feel invisible.

I was a tomboy and a daydreamer. I was shy around boys and people I didn't know but confident when speaking up in class. I didn't have a boyfriend in high school until my junior year. His name was Jose. He was Cuban, and a "redbone." Jose's parents greeted me with politeness but not much warmth the day I met them. I knew immediately that they thought I was too dark for their son.

Perhaps I began scribbling the first lines of this book on the slate of my unconscious on the near-tropical summer day that my mother told me not to play in the sun.

I don't remember my response to my mother's admonition. Memory is at best a mere suggestion, at worst a fiction we would bet our lives on. No, I don't remember everything about the day my mother spoke a series of words that were both edict and verdict. Words that nested beneath the tender flesh of my heart and that grew like the hardiest kudzu, impervious and confident, with a will entirely their own.

There is much that I don't remember, but I can still recall the shame I felt that my mother in one sentence had judged the worth of my brown skin (negatively), dictated the necessary course of my matrimonial future, dabbled into the murky world of genetics and DNA, became complicit in the psychological oppression that victimized us both, and reinforced the larger culture and my community's traditional command to girls who looked like me: "If you're black, get back."

Of course, back then there was no way I could articulate or comprehend the breadth of what my mother had accomplished by her words. Still, I knew I had been given a life sentence. But I am sure that to spite my mother and to assert my will, headstrong and stubborn, I continued to play in the sun.

There are so many words and phrases to describe African Americans' pernicious, persistent dirty little secret--colorism, color-conscious, color-struck, color complex. And then there are the more specific descriptive terms that separate Blacks and create castes, and cliques, and that are ultimately definitions not of color but of culturally defined beauty and ugliness, and that can end up distributing everything from power to wealth to love. High yellow, high yalla, saffron, octoroon, quadroon, redbone, light brown, black as tar, coal, blue-veined, cafe au lait, pinkie, blue-black.

But that day my mother spoke none of those words. She didn't have to, for by then I had absorbed everything I needed to know about color. I knew how deeply embedded was the culture's obsession with White-defined beauty, whether it was manifested in the icon status of Marilyn Monroe, or the light-skinned, "good-haired" Black women smiling from the cover of Jet or Ebony. Ebony and Jet were, in the years of my childhood and adolescence, the premier tabloid barometers of Black political and social reality. They were also a kind of scrapbook in which the masses of Negroes got to see proof-positive of the success and upward mobility of the most prominent members of the race. And while there were brown to black men and women profiled in these "bibles" of the Black community, it seemed to me that the Negroes who had managed to pull off the most amazing feats of achievement (Massachusetts senator Edward Brooke, Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall), those we referred to as "Negro Firsts" were usually light-skinned.

I was eight years old the day my mother warned me not to play in the sun and I already knew that I was invisible. I had not read Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. Toni Morrison had not yet written The Bluest Eye. But already I had tasted the essence of racial and colorist tragedy. I feasted on it every day. I had parents who loved me, a nurturing family, many friends. I was smart in school, was often considered the teacher's pet. And I also knew that the specific physical traits that comprised my racial identity were despised.

Words had informed me of this. The words from family and friends that showered praise and compliments on lighter-hued, straighter-haired children for their beauty, words that I never heard used to describe me or other brown to black children. Words like "Isn't she so pretty?" uttered with a sharp intake of stunned breath, eyes bulging in near disbelief at the sight of a curly-haired, light-skinned toddler. Words like "Just look at that hair!" (it was long, straight, thick), "Look at those eyes!" (maybe they were light brown or green or gray). All the words I heard. All the words I read. And for a long time, all the words I could imagine thinking or writing supported skin-color apartheid. As a child, I already knew that the world was a pigmentocracy. And I knew where I fit in that hierarchy.

In the 1950s I grew up in a largely segregated world. The only White people I came into contact with were teachers at school and a few fellow students in the even then majority Black school system of Washington, D.C. So I rarely heard directly from the lips of Whites words addressed to me or to other Blacks that assessed our relative beauty. But Whites had created another ongoing, invasive, and seductive and powerful conversation about beauty and color through movies and television and magazines and books and the collective imagination. And the language of that conversation was not only an echo of the self-hating dialogue among Blacks about skin color but also its progenitor.

"Don't play in the sun. You're going to have to get a light-skinned husband for the sake of your children as it is." Say the words silently. Listen to them and hear the anguished reverberation of the voice of three hundred years of mental suicide. The admonition is filled with so much fear, and so much dread. The sun, which is a symbol of life, growth, and power, in my mother's warning becomes a threat, a harbinger of danger. My mother's words were filled that day with as much emotion as trembles in the voices of mothers today, warning their children not to play in the sun because of the fear of skin cancer. And yet for my mother, darkness, blackness, in its own way was a kind of disease whose progress, in its assault on me, she felt she had to try to halt.

I had seen the famous Coppertone ads for suntan lotion. I knew that White people worshiped the same sun that my mother warned me against. But I also knew that Whites' desire to possess a glaze of color in the summer did not mean they wanted to be Black. I knew that Whites could despise blackness and yearn for some measure of it at the same time.

I always had to be vigilant. Blackness, darkness, and its assumed resultant calamities could silently invade and possess me, even as I was engaged in innocent games of play. The threat of blackness hid, silent, waiting, even in the powerful lightness of the sun.

"You're going to have to get a light-skinned husband for the sake of your children." I was lost. It was too late to save me from darkness, but if I married a light-skinned man there was hope for my children.

My mother was well aware that the world attempted every day to erase me. She knew how little love lay in wait, how few open arms stood ready to embrace little brown-skinned girls with nappy hair and Negroid facial features. My mother had not constructed that world. Unable to challenge the beliefs about beauty and self-worth that she had inherited and that had shaped her attitudes, my mother strove nonetheless to warn me of the pitfalls and traps of the world she had not made but knew not how to destroy. From the vantage point of the present, I know now that those words, so harsh, and so brutal, were offered to me not as the punishment I heard but as an act of love and protection.

In the fall of my freshman year in college, 1968, I Afro my hair. For the first time in my life I love what I see in the mirror. I have never noticed the way my smile unfurls like a proclamation, the velvet depth and softness of my brows, the real color of my skin--a warm, intense brown. I realize I had never before looked at the face God gave me. I have spent years looking at my face through a swirl of conflicted emotions. Surely there must have been a time before this moment, before this day, when I looked at myself without judging, with acceptance. Surely. Surely. But I am a Black girl in a culture that convinces even the White girls I once fantasized about being that they are never quite enough. White, yes, but never ever thin or pretty enough. So how could I, a brown-skinned, unextraordinary (I have believed until now) girl with coarse hair, gaze upon myself as a work of art? Until now I have never before heard so many people affirm that Black is beautiful. And if Black is beautiful, I am too. Behind the locked bathroom door I sit on the rim of the tub, weeping for the perfect rightness of the face, weeping for the years I looked at it and decided not to look too hard. Never to look at it too deeply. Never to really claim it as mine. Black consciousness literally saved my life. The tide of history rescued me from a self- and culture-imposed sense of oblivion. The Black Consciousness Movement of the sixties allowed me to free myself from the prison of my mother's judgment that my color was a crisis, my color was a tragedy, my color was something to overcome.

Why do we remember the words of our mother more than any other? Why does a mother's assessment of her daughter resonate in the chambers of that daughter's heart like the Ten Commandments? Like the laws of gravity? Like a destiny that you simply cannot escape?

In college because I was Black and beautiful I made up for lost time. And it was in college that I became a color democrat. I dated Nigerians, Trinidadians, brothers from Harlem, from D.C. and Philly. I dated Howard University Black Power-spouting revolutionaries and working-in-the-system journalists. The men I dated, the men who were drawn to me, the men who became my lovers and my husbands, have spanned the color and racial spectrum. Color became incidental to me in choosing a partner. What was the man doing with his life when I met him? Where was he headed? How big were his dreams? That's all that mattered to me.

Color is in many ways an illusion. It is a game we play. It is subjective. We judge color not with our eyes but with our emotions. Our prejudices. Our longings. Our fears. Our hearts. My husband, Joe, my first boyfriend, like Jose, is a "redbone" in my eyes, but considers himself to be much darker than I see him. He is the lightest member of his family and he has told me that as a child, in the midst of his siblings, he sometimes felt that he did not really belong, because he was so light. His family did not make him feel uncomfortable because of his color, but he was teased by other children. I am convinced he sees himself dark in order to assert that despite his light skin he "belongs" among his family, his kin.

Don't Play In the Sun: One Woman's Journey Through the Color Complex

- hardcover: 208 pages

- Publisher: Doubleday

- ISBN-10: 0385507860

- ISBN-13: 9780385507868