Excerpt

Excerpt

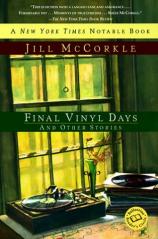

Final Vinyl Days

Dysfunction 101

My friend Mary Edna goes out every night of the week. She has a few drinks and then dances until they close the door of Roy's Holiday Lounge. It's on I-95, so she's forever meeting folks passing through town. One day she dances with somebody from Dixon, Illinois, and then it's Richmond, Virginia, and of course she has a steady batch from the army base just an hour away. Once she met somebody from Saudi Arabia (she said Saudia Arabia), and she talked about that for weeks, as if touching his dark hairy hands (her description) had linked her to lands and histories unknown, like he might be an oil sheik and come a calling again. Lord. She wears their towns like badges, remembers them better by the sorts of details that a tourist might remember than she does hair or eye color (she does always provide that information as well, though it's clear after years of this that she is not a choosy woman). I suggested once, in a moment of sarcasm, that she get one of those big maps and start sticking pins in it, like all those richer-than-thou folks who have in mind seeing every square inch of the planet. I said, "You can get different colored pin heads--fast dancer, slow dancer, smoker, joker, poker, toker, and any of the above." She claims that the only time she ever slept with one of her late-night acquaintances was with the one with cancer who had never had oral sex. It was on his list of things to do on earth--it was right under "see the Grand Canyon" and right above "eat snails and frogs in a French diner." She sure can pick them.

I have tried on many occasions to adopt Mary Edna's children; I feel I might as well, since all those nights their mama is out playing around, they are here at my house taking bubble baths and doing their homework. They stare at me with round brown eyes while we sit around my kitchen table, all three of us in footie pajamas. I rent movies like Thomasina and The Parent Trap and Old Yeller, and we eat big bowls of ice cream with Hershey's syrup, just like I did when I was a kid--like I did with Mary Edna beside me in the house on Fourth Street, my grandmama's house. I thought the two of us would grow up to catch the world by its tail like a comet, and now I look at us and wonder what on earth happened. I told her just the other day that this was what I was wondering, and she asked, who did I think we were, those idiots who committed suicide in hopes of riding a comet? I realized right then that we did not have the same memories and never would. We were two girls with so much in common, and yet we had walked away with such different messages; hers was find a man, any man, and mine was find a decent man--a kind, smart, hard-working, loving man, with something on the brain other than what is edible, and if you don't find him, stay by yourself and get a few friends at the SPCA.

What did Mary Edna and I have in common all those years? We were the two girls at school who were not in what the teacher called "a traditional home." Every time that phrase was spoken people turned around in their seats and stared at us. Mary Edna grinned and waved at everybody like she might have been the homecoming queen, but I hated those moments. I kept saying to Mary Edna, "That kind of attention is not good," but she didn't hear a word I said. She believed then (as she still does) that any attention is better than nothing. And she got plenty of attention with botched-up marriages and unwanted pregnancies, one drug bust and one shoplifting scene (two padded bras and a lime green dickey from J.C. Penney). I told her I would have given her the money, maybe not for that ugly dickey, but for practical underwear items that she needed, yes, I'd've bought those. I told her that while she was out getting herself all the attention that she missed as a child because her parents were do-nothing alcoholics, her own children were suffering. But again, she did not seem to hear.

Mary Edna lived with her mother's various relatives and whoever from the church invited her home, and I lived with my grandma because my mother was too young to be a mother; my mother wanted a chance in life, and Grandma felt like she deserved that. I think of it as the chain reaction of mamas. Everybody is guilty; everybody is trying so hard to make up for her mama's failures. We all learn from one another. For example, my grandma used to always say "work like a nigger," and I had to preach long and hard for years to convince her that it did not sound nice. She said it wasn't racist because they did work hard, and I gave up explaining the point. Still, she has come around enough that now she'll get that n sound coming through her nose and then catch herself. Now she says things like "He works like a n-n-nun" or "She works like a noogie."

"A noogie?" I asked, and she waved her hand and said I knew what she meant. Grandma and I aren't where we should be but we keep on moving. She is all I have.

And come to think of it, I guess that's where my life differs from Mary Edna's. At her house everything was coarser, shakier. She claims her mother's first cousin never touched her but that she was always scared he might, that his face haunted her, and she discovered early that the more men she was with, the further she could get from that feeling. He is doing time by now, anyway. Her third ex-husband is probably the only person other than me and my grandma who ever really loved her, but he finally gave up and married a quiet, nearly homely woman from a neighboring town. I think he got as far from Mary Edna and her need to make somebody hurt her as he could--both of them running like rabbits, leaving the girls to stare out at the world with their round-eyed fear. They are four and five, dark-eyed beauties who deserve a hell of a lot better. I have thought of stealing them and driving to the west coast, except that would be one more example of running, and I think more than anything they need a spine of steel; they need to stand tall until they can safely walk forward. These days more kids are not in "a traditional home" than are--and those that are will one day go into a therapy office and say how very lucky they were, or they will say how the facade of a traditional family does not a traditional family make. There is no human with the answers.

Speaking of dysfunction and mama failures, I only met my mama once, and she was an absolute mess. My grandma said, "This is what I gave up my life for you to do?" My mama sat there like a big overstuffed chair, her toenails looking like she'd been digging potatoes. Mary Edna has always said that that's why she's big on painted toenails in the summer; you can hide the dirt. I told her that soap and water is another fine way to deal with the dirt--you can get rid of that dirt if you desire. That's what I wanted to tell my mama. I wanted to say, "Liberate yourself--shed that filth and pestilence." I wanted to tell her that mothers don't come with a warranty; that she could at least try to make it up to me. I was, after all, trying so hard to forgive her, especially if she bathed and did something with her hair. Her name is Ashley Amelia, and I had spent much of my childhood mooning over that name and creating wonderful romantic adventures for my mother in my head. The one picture my grandma had of her was from a high school yearbook where she looked no different from the other girls lined up there in the home ec class. My grandma could almost always kill a fantasy with warnings like "Things ain't always as they look, sound, or smell."

I recently read that all of these foreign people were given a list of English words and asked to select which one sounded most lovely. Nine out of ten people chose "diarrhea." This certainly seemed to fit my life. I hope those people weren't embarrassed when they found out what their chosen word meant. I hope they just shook their heads and laughed about how you just can't count on anything to be as it appears.

My mother was having trouble acting like a mother. It was more like she was my long-lost sister or cousin; she got along fine with Mary Edna. She showed us pictures of the latest man to dump her, and my grandma and I both shook in fear to see such an ugly face. For all the things my grandma had always said about the boy who had fathered me--a thick thatch of hair parted too far to the right, so that it pitched off like a rooftop (deceiving hair, because it made him seem sweet, when really he was the devil incarnate)--he was far superior to this thing in the photo. She stared down at his ugly face (even Mary Edna couldn't bear to look at the photo, said it stunk fumes off the paper) like she was in a stupor and said she didn't know why he treated her so bad. She said his words sometimes were so mean they cut her to the bone, though for the life of me I couldn't see a bone through that balloon of a body. I kept thinking that his words must have punctured, sliced like a knife does a melon. He ate what was edible and trashed the rest, and she had been rotting ever since, carrying that sweet, rotten smell of decay in her every pore and crevice. When she said she guessed she better head to the bus station, my grandma did not try to stop her, as I'm sure she wished somebody would. My grandma said she couldn't afford to keep her around and give her the liquor that without a doubt was close to killing her. Grandma said that when the time came, she wouldn't even need to be embalmed. I pictured this huge woman bottled up like those old pickled eggs they used to sell in the little grocery store down the road.

"My mama is all but dead," I kept thinking, and when she opened her arms to hug me, I felt like my heart was breaking. Here she was, already a ghost and replaced with this fleshy apparition.

If I was a child I might've been shuffled off to DSS but instead my friend Elizabeth, the third-grade teacher I am the assistant for, came and took me out to lunch, got me to talk about these things, cry a little bit. Elizabeth is a saint. If Mother Teresa had been five feet nine inches with wild red hair and was pro-choice, that would be Elizabeth. Sometimes I like to stand and look in through the glass of her front door and see her inside with her husband and baby; just this glimpse is all I need to make me hang on for what will be right for me. I want things to be clean, sober. I want Mary Edna to want the same things, but she is nowhere near seeing it all my way.

The only other thing I know about my daddy was told to me that day my mother came to visit. When he was a boy he had two cats he liked to torture. Their names were Uddnnnn and Errrrrnt, so that when my daddy went outside to call them, it sounded like a car wreck. A car wreck sounds like such a pleasant event compared to spending time with him. And why did somebody named Ashley Amelia choose such a loser? Maybe because her own mother threatened her husband that she'd kill him if he didn't take to the road and never return. There are some people who are not entirely convinced that my grandma didn't do something to him. Such is my legacy.

Way back, when I was on a scholarship at the junior college nearby and thought I needed to get married to be safe in this world, I often kept a boy in my room. I liked the way that a boy looked propped up on my bed, like something you might win at the fair. One of them was real cute but not too swift at all. A real limited vocabulary, limited mainly to well I'll be goddamned or Ain't that some shit. He was real handsome, when he was all cleaned up, but I couldn't stop thinking of his head as a maraca, like the ones I loved to shake in elementary school; he had little tiny specks of information rolling around in his head and making enough sound that he didn't seem like a zombie. Another boy who liked me a lot I let go, due to the fact he smelled like a chicken.

"Don't you know?" Mary Edna asked me while laughing hysterically. "All the unknown things in life taste and smell like chicken."

I said that I didn't say "chicken" but "a chicken," like that coop we grew up down the road from. The smell of chickens in a coop has nothing in common with the Colonel and his seven secret spices. I told her that she had to change the way that she looked at men, that it was like upgrading your car or anything else in life. At the time she was dating a man whose idea of a good time was renting those red-shoe diary videos and ordering out for pizza. I met him once, and he invaded my space so entirely that I could smell his gingivitis. When I told Mary Edna this, she said I should be ashamed, like I might have really sniffed this jerk around the butt like a dog. I said, dental hygiene? You know bacteria, decay, death within life? Unflossed gums like an unplowed field. Rotten. She looked at me like I might be insane, and I thought then we had moved so far from each other that there was no hope of us ever conquering the world.

I love to floss my teeth. I like the thought of how you can take pulpy, unhealthy gums and floss them until they are tough and ready, no longer bleeding. There's enough blood in this world without what is unnecessary and completely avoidable. That's how I see the children I work with. Elizabeth has talked me into going back to school, and in a few years I'll have my own classroom. I might have Mary Edna's children with me.

I fall asleep at night while creating my future. I make my grandma color-blind. I tell her to give me a little bit of a smile, work those muscles so she will keep her face in shape, like old Jack Lelane--as ancient as he is, he keeps teaching. I give her a freezer full of frozen Baby Ruths (her very favorite), and I buy her that fancy sewing machine she has wanted forever. And then I start telling lies, as many of us do as a form of survival. I tell her that she ought to forgive herself for the way my mother turned out, that it wasn't her fault at all. I tell my mother that I'm sorry her life took such bad turns, that it wasn't her fault at all, that she could still climb up and out of that hole and start over. I tell her that just because your back tire gets stuck in a muddy field doesn't mean you ought to drive the whole car in. I give her a case of Ivory soap and thick nubbly washcloths to cleanse herself; I give her a new dress and a new hairdo and a daughter who in my opinion has turned out damn well. I tell her I wish I had the power to send her back to the time of that high school photograph and give her a second chance, but I can't. And that's what is really the sad part. I can't change a single thing in her past, and even if I could, I don't know now that I'd want to. Who knows where I would be if things had not happened as they did?

First, you recognize what was wrong, I tell Mary Edna's girls every chance I get, and then you accept it. This does not mean that you agree with it, just that you say, yes, that is what happened. And then you walk off and leave it there; it is not your mess to clean up. Right now I use that speech when I'm talking about the neighbor's dog who uses the sidewalk for his toilet, or when some child gets mad and throws toys around the room in a tantrum. But there will come a day when I have to say it in reference to their mother; I like to think they will be relieved.

Final Vinyl Days

- paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0449005747

- ISBN-13: 9780449005743