Excerpt

Excerpt

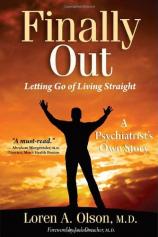

Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight, A Psychiatrist

Chapter 2: It’s Just Common Sense

Out beyond ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

--- Jelaluddin Rumi

“Am I gay? Bisexual? A latent homosexual? Or a heterosexual with issues?” While hiding as they search for answers to these questions, mature men who are sexually attracted to other men find themselves caught in the crossfire between those who consider them an abomination and those who think of them as hypocritical, self-hating, closeted gay men. Those searching for answers, however, might not be asking the right questions. Rather than searching for a label that fits them, these men could be asking: “How can I understand, accept, and experience the complexities of my sexuality and align it with my values?” But it is easier just to choose a label and let the label define you.

One steamy hot day in August when I was three years old, my dad was making hay. He had hitched a young, high-spirited horse with limited training to the steady and responsive older horse from another team, a common practice in breaking a new horse to drive. My father was working alone. Suddenly, something spooked the horses. They bolted, running at full speed back to their barn, dragging the hay wagon --- and my father who was tangled in the harnesses beneath the horses. My father died several days later, never having regained consciousness.

To reconstruct some image of my father I created a montage from other people’s memories of him. When I was young, I would ask my mother about him, but she had canonized him and her description was more divine than mortal. I knew that I could never be just like him. Once when I was in a high school play, I needed to wear an outdated suit. My mother said that she still had my father’s suit in a trunk. We went to the attic together. As she dug through the chest, she found his suit under her mother’s wedding veil and old pictures of relatives I didn’t remember. She removed it from the trunk and pulled it to her chest. She began to cry softly, and said, “I can still smell your dad on his suit.” I tried the suit on for size, but it was too small for me. I was too big for the suit, but I could never fill my father’s shoes.

I didn’t know what my father looked like. I didn’t know the sound of his voice. I envied my mother’s ability to remember the smell of my father, for I didn’t even have that memory. I need a father as a hero and a mentor. The biased and fractured template of a man provided by my mother was all I had to use for a role model. Long before I questioned being gay, I believed that it was my father’s death --- and the lack of a role model --- that informed my feelings of being an unfinished man.

After I had been married several years I asked a cousin, Gaylund, to tell me about my father. Our conversation lasted well into the night. “Tell me some dirt,” I said. “I need some balance, something to bring him down to earth.” I thought my cousin might have heard something in his family that would pluck a few feathers from the wings my mother had given him. I needed to make him more accessible to me as a human being. I needed to remove his shroud.

In the Chariot Allegory Plato described our minds as a chariot pulled by two horses. The charioteer represents rationality, and he holds the reins and uses the whip to assert his authority. One horse in the team is well bred and well behaved. The other is obstinate and difficult to control, barely yielding to the whip. As a man experiencing sexual attraction to other men, that desire was like the obstinate and difficult to control horse. Once a man discovers that meeting another man eye to eye --- and holding that contact for just a moment too long --- betrays his interest, he can neither unlearn it nor stop doing it. He forever becomes a participant in this silent communication between men, and therefore is always at risk of losing control over the obstinate and high-spirited horse.

Some have suggested that my father, then only thirty-two, was no match for the spirited team of horses that killed him. But my Uncle Glen, who knew my father best and loved him as much as I do, insists that my father was an excellent horseman. He and my dad would get wild mustangs through the Bureau of Land Management and bring them to our farm in Nebraska. They would break the untamed animals so they could be ridden and later be sold as well-trained horses.

My uncle cried as he described the day of my father’s injury. My father had a well-trained team of horses but wanted to break in this new, partially trained horse he’d recently purchased. He hitched the inexperienced horse with the steadiest and best one in his mature team, trying to train the new addition. My father was alone with the team in the hayfield when something spooked the horses. The two horses came running full bore down the lane and up to the barn pulling the hay wagon behind and my father beneath it. As they reached the barn, they found themselves stopped abruptly because the hay wagon was too wide to fit through the doorway. Even a good horseman is not always a good match for untamed horses. Pope Benedict XVI, while still Cardinal Ratzinger, apparently didn’t put much stock in Plato’s allegory. He wrote that the essence of being human resides in one’s reason, and our conscience must guide our physical passions. Homosexual “inclination,” according to Ratzinger, is not a sin, but homosexuality is “intrinsically disordered.” Cardinal Ratzinger said that homosexual behavior is not a right. He also said that no one should be surprised if violence is directed at those who engage in homosexual behavior --- an all too feint condemnation of violence based on hate.

Many gay men believe that once a man has been tempted to homosexual behavior, he has little choice but to give in to it. Charles Darwin thought sexuality was biologically determined. In The Descent of Man, Darwin wrote: “At the moment of action, man will no doubt be apt to follow the stronger impulse; and though this may occasionally prompt him to the noblest deeds, it will far more commonly lead him to gratify his own desires at the expense of other men.” The subtext of Darwin’s message is evident: We frequently do not operate using only rational thought even when our decisions have painful consequences to others. It is in this contentious and rigid environment that men and women who are attracted to members of their own sex often enter when seeking answers to questions about their sexuality.

When we speak of the “self,” we are talking about the core of our being, the uniting principle that underlies all of our subjective experiences. The self incorporates our genetic programming with the lessons our parents and culture have taught us. We cannot change our genetic makeup, at least not as of yet, but as humans we can use our gifts for self-examination and analytical thinking to examine our values and what we have been taught. Buddha got it right when he wrote in the Dhammapada, “Your worst enemy cannot harm you as much as your own mind, unguarded. But once mastered, no one can help you as much, not even your father or mother.”

N. B: Buddha said, “Your worst enemy cannot harm you as much as your own mind, unguarded. But once mastered, no one can help you as much, not even your father or mother.”

Many resist Darwin’s idea that humans aren’t always capable of operating with rational thought. They believe that God gave man a special gift --- the gift of reason --- that elevates us above other animals. With it, they believe, we always have the capacity to deliberate and decide, to analyze the alternatives, and to weigh the pros and cons. But decisions aren’t made using a series of computer chips. While we may wish to ignore our feelings, we respond as flesh and blood engaged in a palpable world. We have the capacity to deconstruct our inherited value system, analyze it, and reconstruct a value system of our own making; in fact, it is essential that we do so. But too much thinking can also lead us astray or paralyze us into stagnation.

Those who believe that there are absolutes of right and wrong and good and evil have had their thinking done for them. A book like this won’t be of help to those people, because they will sort their experiences in the world, including what they read, to conform to rigid, preordained beliefs. For me, successfully understanding, accepting, and deciding how to live into my sexuality required questioning, analyzing, and reassessing some fossilized values that I had never questioned before.

N. B.: If you believe there are absolutes of right and wrong, someone else has done your thinking for you.

Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight, A Psychiatrist

- paperback: 280 pages

- Publisher: inGroup Press

- ISBN-10: 1935725033

- ISBN-13: 9781935725039