Excerpt

Excerpt

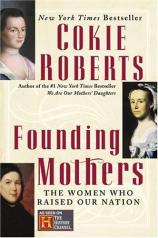

Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation

Chapter One

Before 1775:

The Road to Revolution

Stirrings of Discontent

When you hear of a family with two brothers who fought heroically in the Revolutionary War, served their state in high office, and emerged as key figures in the new American nation, don't you immediately think, "They must have had a remarkable mother"? And so Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Thomas Pinckney did. Today Eliza Lucas Pinckney would be the subject of talkshow gabfests and made-for-TV movies, a child prodigy turned into a celebrity. In the eighteenth century she was seen as just a considerate young woman performing her duty, with maybe a bit too much brainpower for her own good.

George Lucas brought his English wife and daughters to South Carolina in 1734 to claim three plantations left to him by his father. Before long, however, Lucas left for Antigua to rejoin his regiment in fighting the war against Spain, leaving his sixteen-year-old daughter in charge of all the properties, plus her ailing mother and toddler sister. (The Lucas sons were at school in England.) Can you imagine a sixteen-year-old girl today being handed those responsibilities? Eliza Lucas willingly took them on. Because she reported to her father on her management decisions and developed the habit of copying her letters, Eliza's writings are some of the few from colonial women that have survived.

The South Carolina Low Country, where Eliza was left to fend for the family, was known for its abundance of rice and mosquitoes. Rice supported the plantation owners and their hundreds of slaves; mosquitoes sent the owners into Charleston (then Charles Town) for summer months of social activities. Though Wappoo Plantation, the Lucas home, was only six miles from the city by water, seventeen by land, Eliza was far too busy, and far too interested in her agricultural experiments, to enjoy the luxuries of the city during the planting months.

The decision about where to live was entirely hers (again, can you imagine leaving that kind of decision to a sixteen-year-old?), as Eliza wrote to a friend in England in 1740: "My Papa and Mama's great indulgence to me leaves it to me to choose our place of residence either in town or country." She went on to describe her arduous life: "I have the business of three plantations to transact, which requires much writing and more business and fatigue of other sorts than you can imagine. But least you should imagine it too burdensome to a girl at my early time of life, give me leave to answer you: I assure you I think myself happy that I can be useful to so good a father, and by rising very early I find I can go through much business." And she did. Not only did she oversee the planting and harvesting of the crops on the plantations, but she also taught her sister and some of the slave children, pursued her own intellectual education in French and English, and even took to lawyering to help poor neighbors. Eliza seemed to know that her legal activities were a bit over the line, as she told a friend: "If you will not laugh immoderately at me I'll trust you with a secret. I have made two wills already." She then defended herself, explaining that she'd studied carefully what was required in will making, adding: "After all what can I do if a poor creature lies a dying and their family taken it into their head that I can serve them. I can't refuse; but when they are well and able to employ a lawyer, I always shall." The teenager had clearly made quite an impression in the Low Country.

The Lucases were land-rich but cash-poor, so Eliza's father scouted out some wealthy prospects as husband material for his delightful daughter. The young woman was having none of it. Her father's attempts to marry her off to a man who could help pay the mortgage were completely and charmingly rebuffed in a letter written when she was eighteen. "As you propose Mr. L. to me, I am sorry I can't have sentiments favorable enough of him to take time to think on the subject ... and beg leave to say to you that the riches of Peru and Chile if he had them put together could not purchase a sufficient esteem for him to make him my husband." So much for her father's plan to bring some money into the family. She then dismissed another suggestion for a mate: "I have so slight a knowledge of him I can form no judgment of him." Eliza insisted that "a single life is my only choice ... as I am yet but eighteen." Of course, many women her age were married, and few would have brushed off their fathers so emphatically, but the feisty Miss Lucas was, despite the workload, having too much fun to settle down with some rich old coot.

Eliza loved "the vegetable world," as she put it, and experimented with different kinds of crops, always with a mind toward commerce. She was keenly aware that the only cash crop South Carolina exported to England was rice, and she was determined to find something else to bring currency into the colony and to make the plantations profitable. When she was nineteen, she wrote that she had planted a large fig orchard "with design to dry and export them." She was always on the lookout for something that would grow well in the southern soil. Reading her Virgil,she was happily surprised to find herself "instructed in agriculture ... for I am persuaded though he wrote in and for Italy, it will in many instances suit Carolina."

By her own account, Eliza was always cooking up schemes. She wrote to her friend Mary Bartlett: "I am making a large plantation of oaks which I look upon as my own property, whether my father gives me the land or not."

Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 006009026X

- ISBN-13: 9780060090265