Excerpt

Excerpt

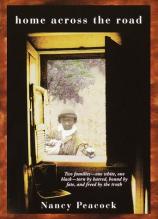

Home Across the Road

China

In 1973, China Redd was waiting to die. She was sixty-one years old and had been waiting to die for two years now, waiting even though death would not come. Death would not come even though China's eyes were rheumy and clouded, even though her back was bent and frail. Even though her hands shook and her breath felt shallow, like it wasn't getting down into her body, like the air wasn't going to all the places that a breath is supposed to go.

Her granddaughter, Abolene, told her that she wasn't sick. The doctor put the cold round disc of the stethoscope against the bones of China's thin brown chest and declared her healthy as a hog.

Young, both of them. What would they know about dying or about the tiredness she felt in her bones and her soul?

Only China Redd knew how it felt to be inside her body and she had spent sixty-one years inside that body, forty-four of them asking hardly anything but work out of it, asking nothing but work from her hands and her bones and her back and her arms.

The work began in 1926, on the day she turned fourteen, when China Redd followed her mother down the narrow dirt-packed track leading from their home and into the oak-lined driveway of the home across the road.

China Redd was tall enough, even then, to reach the key that hung off a string from the new light fixture on the back porch of the big house called Roseberry. She slipped the key into the lock, turned the knob and stepped into the dark kitchen. China could feel its space all around her and her mother picked up her hand and guided it along the wall, showing her the push-button switch that flooded the kitchen with modern electric light.

At age fourteen China started working for the white Redds in the big old house called Roseberry. At age fourteen China Redd began a lifetime of mornings spent cracking eggs into a bowl and brewing coffee and spreading softened butter across bread that was toasted the color of her skin.

For forty-four years China slid a key into a lock and let herself into a back door. She scrubbed Roseberry's floors and polished its silver and watched its babies grow up and leave home. She rinsed out washtubs and bathtubs and cooked and folded laundry and swept and vacuumed. She had seen its weddings and its showers, its wakes and its funerals. She had seen its bridge games and Christmas parties and Easter dinners. She had fed and bathed and wiped the noses of children that were never her own and now, as China Redd waited to die, the big old house called Roseberry stood as empty as she felt herself to be.

Windows were broken out and doors left ajar. Floors that China had shined were now scuffed and dulled with films of dust and dirt. Names of teenagers were spray painted across cracked plaster walls. Dishes were broken and scattered across the cracked gray linoleum of the kitchen floor, and sitting in an open cabinet was a fluted white bowl with a bird's nest cupped inside.

In the dining room of Roseberry, a wisteria vine had broken through the window and twined itself around the very table legs that China had crawled on her hands and knees to polish. It wound itself around chairs and crawled across the mahogany table, and trapped inside its jungle were the dishes of Coyle Redd's last meal, still crusted with food that China had cooked.

It seemed to China that nothing she had ever done mattered anymore, if it had ever mattered at all. Not one pan that had been carefully washed, not one stain gotten out of a white linen shirt, not one wrinkle ironed out of slacks or sheets—none of it mattered now.

Children grew up and went away, sometimes forever, sometimes to places unknown, sometimes for reasons that could never be understood. No doubt Abolene would be leaving soon, leaving and taking China's great-grandbaby and all the life of the house with her. Soon China's house would be left as empty as Roseberry was left on the day that Coyle Redd died.

Coyle Redd was the last of the white Redds and he was gone forever now. He was gone and China's own son, Earnest, had vanished one day eighteen years earlier and there wasn't any reason to hope anymore that he would come home. China was tired of waiting for him but she didn't know anything else.

China didn't know anything else but waiting. All her life she had waited on the needs of the white Redds. When Earnest was a child she had waited on his stuttering words to form a sentence. When he had disappeared she had waited for him to come home but there was no point in that now, so instead she waited to die.

She would wake up in the mornings and creak her legs over the edge of the bed, testing the floor with her feet. If the soles of China's feet felt the hard braid of the rug, then China knew it was another day and she asked God how much longer.

"How much longer?" she would say as she crept down the hallway and into the bathroom and eased herself down onto the toilet. "How much longer?" she would say as she sat in a rickety white chair at the kitchen table and nibbled a few bites of the breakfast that Abolene cooked for her. "How much longer?" China would ask as she pushed the plate away.

In 1973, Abolene was nineteen years old and the spitting image of her father. She was tall and strong with thick, heavy veins roping across the backs of her hands. She had Earnest's almond-colored skin. She had his deep-set eyes. She had thin elegant fingers, the same as China remembered Earnest's to be. Abolene even had the same cocky walk as Earnest, the same prideful stride that had so often gotten him into trouble with the white men in town. China couldn't help but think of Earnest when she looked at Abolene.

Every morning Abolene set a cup of hot black coffee in front of her grandmother and asked, "Is today the day?"

"I don't think so," China would say. "I don't think He's going to take me today. Maybe tomorrow."

Waiting to die was slow work. There was nothing to do to speed up the process. Nothing that China wanted to do, anyway. So she waited and she thought and she remembered.

After breakfast China Redd would move from the kitchen to the front room where she would slowly sink into the couch. She would shift from side to side, trying to get away from the broken spring that poked its way through the scratchy blue upholstery. If she could see through the window that the weather was nice, China would pull herself up from the couch and shuffle to the porch. She would sit in the old La-Z-Boy recliner and tug at her housedress, lifting first one cheek and then the other, finally nodding to Abolene, who would raise the lever that kicked out the little shelf for China's feet. Abolene would drape an old yellow blanket across her grandmother. She would tuck the edges in around China's spindly legs. She would ask, "Is it okay?"

China nodded.

A few minutes later Abolene would come out on the porch again, wearing her brown K&W Cafeteria uniform and her white nurse's shoes.

"Okay?" she would ask again.

China would nod.

"Give Great-granny a kiss," Abolene would say to her two-year-old daughter, and China would feel the child's sticky lips against her too-soft cheek. She would watch them drive away together in the old dented Valiant that Abolene had bought with her own money.

The car would dust along the driveway and then turn onto the road. The tires would swoosh along the pavement and soon even the engine couldn't be heard and it was quiet and it was just China sitting on the porch in the old La-Z-Boy recliner.

She gazed across the field in front of her. China stared beyond the cows that were grazing there. Her eyes went past the dew-covered spiderwebs that were spread across the grass every morning, like a thousand tossed handkerchiefs gleaming in the bright early light. Her gaze went over the two-lane blacktop, past the chain that blocked the entrance, along the oak trees and the rutted driveway and the weed-choked walkway and up the old gray steps to the porch of Roseberry.

There was no one left alive that knew Roseberry like China Redd. She could recall seeing that house painted white with gray shutters one year and gray with white shutters another. China could recall seeing that house painted in just about every kind of way and she could recall seeing that house with no paint at all when she was a little girl and Roseberry stood across the road, rustic and brown and weatherworn, just like her own little house, just as rustic and brown and weatherworn as it was now.

There were lots of stories about Roseberry, none of them true as far as China could tell. Those stories circulated the town and the county like the ghosts that they were. Those stories were published, published like they were real, published in a book called The Legends of Roseberry, written by a woman named Lydia Redd, one of the white women that China had worked for during her life.

When the book was published, it had been China who had served at the party Lydia Redd threw for herself. It was 1965, the year before Abolene's mother died. The year before twelve-year-old Abolene left her home in Wake County to come and live with China in Chatham.

China remembers clearly standing in the kitchen of Roseberry, arranging celery sticks and slices of cheese and carrot strips across a glass platter. She remembers clearly hearing the squeak of the swinging door behind her as one of the guests pushed his way through. She remembers the footsteps and the soft pad of shoe leather on linoleum and the way that he came to lean against the counter beside her.

"Mrs. Redd tells me that you're descended from the slaves that worked this plantation," he said. He picked up a piece of celery and crunched down on it. "Is that true?"

"That's true," China said but that was all she would say. In 1965, China Redd didn't want to talk and even if she had wanted to talk she wouldn't have expected to be heard.

China Redd had stories inside of her, stories that clawed at her throat like an untreated virus, stories that would probably never see the pages of a book, but books were not what made things true.

China Redd knew that her stories were true. She knew it from the earrings that she had in her own possession, and if that wasn't enough, there was a picture inside of Lydia Redd's book of those very same earrings, earrings that China's great-grandmother had stolen from the white Redds.

China's great-grandmother was born in a small cabin behind the big house called Roseberry. China's great-grandmother was a woman named Cally, born with brown skin and blue eyes. But those eyes were not blue on the day that she was buried.

If someone had asked how such a thing was possible, China would have told the truth. She would have said it is only grief that can change the color of a woman's eyes.

Home Across the Road

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: Bantam

- ISBN-10: 0553381024

- ISBN-13: 9780553381023