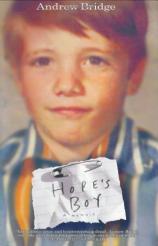

Hope’s Boy: A Memoir

Review

Hope’s Boy: A Memoir

Andrew Bridge loves his mother. This is a certainty you will carry away after reading this harrowing memoir of a little boy lost --- taken away by the system, then trapped in it, abandoned not by his mother but by departments and laws and social servants. In all, as a child, Andrew had two years with Hope, the mentally ill girl who gave birth to him at age 17 and tried her best to make a home for him in her own nightmarish hand-to-mouth existence.

Once you read HOPE’S BOY you will find that many of your ideas have changed. If you never really thought about foster care, you will now. If you thought foster care was a benign and necessary system, you will challenge that assumption every time the subject comes up. If you thought that parents whose children wind up in foster care are all criminals and monsters, you will have to think again.

The statistics are grim. Referencing the area where he was fostered, Andrew Bridge, now a lawyer who battles for the rights of foster children, states, "Over the last decade, dozens of children have died in Los Angeles foster care and hundreds more have simply disappeared." And "over half a million American children live in foster care. The majority of them never graduate from high school, and overwhelmingly they enter adulthood only semiliterate… thirty to fifty percent of children aging out of foster care are homeless within two years."

After Andrew was separated from Hope (and yes, that is her real name) --- torn physically from her on a city sidewalk as he pulled at her, she screamed and the neighbors looked on --- he was put in a large institution that is the usual first dumping place for such children. Refusing mutely to take off his clothes that first night among so many strangers, he was put in solitary lockup. It was a mistake he never made again.

Andrew must have had some remarkable coping skills, because his first temporary home placement, with a family he calls the Leonards, gradually turned "permanent" until he was released at age 18. Mrs. Leonard was a Baltic refugee who had spent part of her childhood in Dachau and whose perverse treatment of children often seemed to mirror the ugliest aspects of her own early years. Irrationally desperate for money, she took in foster children against her natural children's objections and treated them like unwanted strangers. For birthdays she demanded that the foster child carefully unwrap his or her single present so that the paper and ribbons could be re-used for the next event.

When Hope managed to get to see Andrew, the system, with Mrs. Leonard's eager compliance, cruelly structured the encounters --- confined to one room and strictly timed. Even Mrs. Leonard's natural children and her husband feared her. Yet somehow Andrew stayed while many other children came and went --- girls who had been sexually abused by age seven; boys who, like him, kept their secrets, their past, locked up tight inside. It was a loveless childhood, but it kept a roof over his head and got him through high school.

Andrew wasn't a trusting boy, always convinced that he would be a social pariah if other kids knew his mother wasn't there for him. He managed to override his social fears, however, and achieved many honors in high school, took part-time jobs and determinedly bicycled everywhere so he wasn't dependent on the erratic largesse of the Leonards. He was admitted to Wesleyan College with a full scholarship and later to Harvard Law School.

Between ages 8 and 18, Andrew had a troupe of social workers, but he rarely saw them --- they came to visit but mainly to get reports from Mrs. Leonard. Years later one of those nameless professionals told him that his mother had tried many times, and come so close, to get custody of him. But at the time he was not informed, never given a hint about his mother's continued caring through their separation. This lack of information about children's cases became one of the matters that Andrew sought (successfully) to change once he made the decision to use his law degree to advocate for kids trapped in the system. He is still out there jousting, not just in California but, for example, in Alabama, where in the 1990s he helped investigate a facility in Eufaula where recalcitrant children were locked in a dank basement, and staff abuse (such as inciting fights among the children) was commonplace.

The author emphasizes that every foster child nurses the belief that his mother, her father, will come back, will rescue, will want to pour out the love that normal children take for granted. It is the cherished dream in lives that are generally a bleak landscape of loneliness and emotional emptiness.

Andrew's reunion with Hope just before he left for college is a centerpiece of his story. He writes, "She was not what I had hoped, not what I had rehearsed." She was living in a state mental hospital and worn down by years of stultifying medications designed to keep her from hearing her destructive voices. Yet at the end of that first brief visit, she murmured, "You know, I tried." That is all the affirmation the child Andy and the adult Andrew needed. He will never abandon his mother or blame her for her failures, and will continue to fight for the rights of children who, like him, live in silent, desperate hope.

Reviewed by Barbara Bamberger Scott on February 5, 2008

Hope’s Boy: A Memoir

- Publication Date: February 5, 2008

- Genres: Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher: Hyperion

- ISBN-10: 1401303226

- ISBN-13: 9781401303228