Excerpt

Excerpt

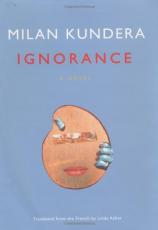

Ignorance

Chapter One

"What are you still doing here?" Her tone wasn't harsh, but it wasn't kindly, either; Sylvie was indignant.

"Where should I be?" Irena asked.

"Home!"

"You mean this isn't my home anymore?"

Of course she wasn't trying to drive Irena out of France or implying that she was an undesirable alien: "You know what I mean!"

"Yes, I do know, but aren't you forgetting that I've got my work here? My apartment? My children?"

"Look, I know Gustaf. He'll do anything to help you get back to your own country. And your daughters, let's not kid ourselves! They've already got their own lives. Good Lord, Irena, it's so fascinating, what's going on in your country! In a situation like that, things always work out."

"But Sylvie! It's not just a matter of practical things, the job, the apartment. I've been living here for twenty years now. My life is here!"

"Your people have a revolution going on!"

Sylvie spoke in a tone that brooked no objection. Then she said no more. By her silence she meant to tell Irena that you don't desert when great events are happening.

"But if I go back to my country, we won't see each other anymore," said Irena, to put her friend in an uncomfortable position.

That emotional demagoguery miscarried. Sylvie's voice warmed: "Darling, I'll come see you! I promise, I promise!"

They were seated across from each other, over two empty coffee cups. Irena saw tears of emotion in Sylvie's eyes as her friend bent toward her and gripped her hand: "It will be your great return." And again: "Your great return."

Repeated, the words took on such power that, deep inside her, Irena saw them written out with capital initials: Great Return. She dropped her resistance: she was captivated by images suddenly welling up from books read long ago, from films, from her own memory, and maybe from her ancestral memory: the lost son home again with his aged mother; the man returning to his beloved from whom cruel destiny had torn him away; the family homestead we all carry about within us; the rediscovered trail still marked by the forgotten footprints of childhood; Odysseus sighting his island after years of wandering; the return, the return, the great magic of the return.

Chapter Two

The Greek word for "return" is nostos. Algos means "suffering." So nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return. To express that fundamental notion most Europeans can utilize a word derived from the Greek (nostalgia, nostalgie) as well as other words with roots in their national languages: añoranza, say the Spaniards; saudade, say the Portuguese. In each language these words have a different semantic nuance. Often they mean only the sadness caused by the impossibility of returning to one's country: a longing for country, for home. What in English is called "homesickness." Or in German: Heimweh. In Dutch: heimwee. But this reduces that great notion to just its spatial element. One of the oldest European languages, Icelandic (like English) makes a distinction between two terms: söknuour: nostalgia in its general sense; and heimprá: longing for the homeland. Czechs have the Greek-derived nostalgie as well as their own noun, stesk, and their own verb; the most moving, Czech expression of love: styska se mi po tobe ("I yearn for you," "I'm nostalgic for you"; "I cannot bear the pain of your absence"). In Spanish añoranza comes from the verb añorar (to feel nostalgia), which comes from the Catalan enyorar, itself derived from the Latin word ignorare (to be unaware of, not know, not experience; to lack or miss), In that etymological light nostalgia seems something like the pain of ignorance, of not knowing. You are far away, and I don't know what has become of you. My country is far away, and I don't know what is happening there. Certain languages have problems with nostalgia: the French can only express it by the noun from the Greek root, and have no verb for it; they can say Je m'ennuie de toi (I miss you), but the word s'ennuyer is weak, cold -- anyhow too light for so grave a feeling. The Germans rarely use the Greek-derived term Nostalgie, and tend to say Sehnsucht in speaking of the desire for an absent thing. But Sehnsucht can refer both to something that has existed and to something that has never existed (a new adventure), and therefore it does not necessarily imply the nostos idea; to include in Sehnsucht the obsession with returning would require adding a complementary phrase: Sehnsucht nach der Vergangenheit, nach der verlorenen Kindheit, nach der ersten Liebe (longing for the past, for lost childhood, for a first love).

The dawn of ancient Greek culture brought the birth of the Odyssey, the founding epic of nostalgia. Let us emphasize: Odysseus, the greatest adventurer of all time, is also the greatest nostalgic. He went off (not very happily) to the Trojan War and stayed for ten years. Then he tried to return to his native Ithaca, but the gods' intrigues prolonged his journey, first by three years jammed with the most uncanny happenings, then by seven more years that he spent as hostage and lover with Calypso, who in her passion for him would not let him leave her island.

In Book Five of the Odyssey, Odysseus tells Calypso: "As wise as she is, I know that Penelope cannot compare to you in stature or in beauty ... And yet the only wish I wish each day is to be back there, to see in my own house the day of my return!" And Homer goes on: "As Odysseus spoke, the sun sank; the dusk came: and beneath the vault deep within the cavern, they withdrew to lie and love in each other's arms."

A far cry from the life of the poor émigré that Irena had been for a long while now. Odysseus lived a real…

Ignorance

- hardcover: 208 pages

- Publisher: Harper

- ISBN-10: 0060002093

- ISBN-13: 9780060002091