Excerpt

Excerpt

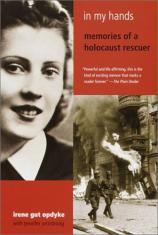

In My Hands

The Villa

The instant I was able to get away after breakfast, I walked to the villa as quickly as I could — quickly enough to put a stitch in my side and to break a sweat in the heat. I unlocked the door and burst inside, dreading the sound of painters bumping ladders against the furniture. But it was silent. I was in time — assuming that my friends were indeed waiting in the basement. The smell of cabbage and potatoes lingered in the air.

Almost fearing what I might find, I opened the basement door and clattered down the stairs, my shoes making a racket on the wooden steps. "Hoo-ee! It's Irene!" I called out.

The first room was empty. Trying not to worry, I opened the door to the furnace room, praying to find my six friends — and Henry Weinbaum. The door creaked as it swung open into the gloom, and I called out again.

"It's Irene!"

There was an almost audible sigh of relief. One by one, figures emerged from the shadows: Ida, Lazar, Clara, Thomas, Fanka, Moses Steiner, and a young, handsome fellow I took to be Henry Weinbaum. I shook hands with them all silently, suddenly overcome with emotion. They were all there; they were safe and alive. And then, to my surprise, I found three strangers, who greeted me with an odd mixture of sheepishness and defiance.

"I'm Joseph Weiss," the eldest of the three said. "And this is Marian Wilner and Alex Rosen. Henry told us."

For a moment I was at a loss. I had ten lives in my hands now! But there wasn't time for lengthy introductions. The soldiers from the plant were due any minute to start painting.

"Hurry, everyone," I said. "You'll have to stay in the attic until the house is painted. I'll check on you as often as I can. I don't need to tell you not to make any noise at all."

This was met with grim nods all around. Then we made our way upstairs. The attic was musty; dust swirled in a shaft of light from the high window, and the air smelled of mouse droppings. "Shoes off," I said. "Don't walk around unless you absolutely must."

I locked them in just as trucks ground to a halt out on the street.

I kicked the basement door shut on my way to let in the soldiers, and then unlocked the front door.

"This way," I said, stepping aside to usher them in with their painting equipment and drop cloths. When I glanced outside, I saw the major climbing out of a car.

"Guten Tag, Irene," he called cheerily.

I bobbed my head. "Herr Major."

"This is splendid," he said, rubbing his hands together as he came inside. "I'll move in in a week or so, when all the painting and repairs are finished, but in the meantime, I'd like you to move in right away, so that you can oversee things. Don't worry about your duties at the hotel — if you can serve dinner, Schulz can manage without you the rest of the time."

As he spoke, Major Rügemer strolled back and forth across the hallway, glancing into the rooms and nodding his approval. His footsteps echoed off the walls, and he muttered, "Ja, ja, ausgezeichnet," under his breath. Then, when another truckload of soldiers arrived, he went outside to meet them and show them around the garden: There were renovations to be made on the grounds, as well. I stood at the dining room window, watching him point out the gazebo and indicate which shrubs and trees should be removed and where new ones should be planted. Behind me, I could hear the painters beginning to shove furniture across the floors, exchanging jokes and commenting on the weather and the sour cabbagey smell left behind by the previous tenants. I heard one of them say "...the major's girlfriend."

I gritted my teeth and prepared to spend the day keeping the soldiers away from the attic.

For the next few days, while the soldiers swarmed around the villa — painting, repairing, replanting — I contrived to smuggle food upstairs to the attic. I took fruit and cheese, cold tea, bread and nuts. I also took up two buckets to use for toilets. The attic was stuffy with the heat of summer, but we were reluctant to open the one window high on the wall. The fugitives had accustomed themselves to much more discomfort than this. They were willing to sit in the stifling heat, not speaking, just waiting. At night, when the workmen were gone and I had returned from the hotel, I was able to give my friends some minutes of liberty. They used the bathroom, stretched their legs, and bathed their sweating faces with cool water. But we did not turn on any lights, and we were still as silent as ghosts.

It wasn't long before the servants' quarters had been completely refurbished; I had seen to that. Telling the workmen that the major had ordered the work to be done from bottom to top, I directed them to start with the basement. Then, when it was finished, I waited until dark and triumphantly escorted my friends to their new quarters, fresh with the smell of sawdust and new paint instead of old cooking.

It was the start of a new way of life for all of us. Several of the men, being handy and intelligent, were able to rig up a warning system. A button was installed in the floor of the front entry foyer, under a faded rug. From it, a wire led to a light in the basement, which would flicker on and off when I stepped on the button. I kept the front door locked at all times, and when I went to see who might be knocking, I had ample opportunity to signal to the people in the basement. One flash would warn them to stand by for more news. Two flashes meant to be very careful, and constant flashing meant danger — hide immediately. We had also found the villa's rumored hiding place: A tunnel led from behind the furnace to a bunker underneath the gazebo. If there was serious danger, everyone could instantly scramble into the hole and wait for me to give them the all clear. The cellar was kept clear of any signs of occupation. Once the men had killed all the rats living in the bunker under the gazebo, it could accommodate all ten people without too much discomfort.

There was food in plenty; Schulz kept the major's kitchen stocked with enough to feed a platoon, and once again, I could not help wondering if he had an inkling of what I was doing. I was also able to go to the Warenhaus whenever I needed to, for cigarettes, vodka, sugar, extra household goods, anything the major might conceivably need for entertaining in his new villa. Of course, the soldiers who ran the Warenhaus had no way of knowing that half of what I got there went directly into the basement, and I was certainly not going to tell them!

The basement was cool even in the intense summer heat; there was a bathroom, and newspapers, which I brought down after the major was finished with them. All in all, the residents of the basement enjoyed quite a luxurious hiding place.

And yet it almost fell apart when the major moved in at last.

"The basement is finished, isn't it?" he asked me when he arrived.

All the hairs on my arms prickled with alarm. "Do you have some plans for it, Major?" I asked, keeping my voice from showing my fear.

He unbuttoned the top button of his tunic. "I'm sure it will do very well for my orderly."

I felt the blood drain from my face, and Major Rügemer looked at me in surprise. "What is it?"

I did not have to fake the tears that sprang to my eyes. "Please don't move him in here," I pleaded. My mind raced with explanations. "I never told you this, but at the beginning of the war, I was captured by Russian soldiers and — and I was — " My throat closed up.

The major frowned at me. "You were what?"

"They attacked me, sir, in the way that men attack women." I saw his face flush, and I hurried on, more confident. "I cannot bear to have a young man living here. It brings back terrible memories for me. Please take pity on me."

Major Rügemer dragged his handkerchief from his pocket and blew his nose hard, shaking his head in anger. "War brings out the worst, the very worst in some people! Funny," he went on, "I always wondered why you didn't have a boyfriend, a pretty girl like you. I've never seen you flirt with the officers the way some other girls might do."

"I can do all the work myself, Herr Major," I pressed. "You will not feel any lack."

He put his hand on my shoulder. "Of course, Irene. I wouldn't dream of making you unhappy."

I smiled up at him. Sometimes it made me cringe inside, to get what I wanted by playing up my femininity. Yet I knew it was the one power I had, and I would have been a fool not to use it. For my pretty face, for the affection he felt for me, the major would let me have my way.

We quickly fell into a routine. Once he had moved in, Major Rügemer left for the factory every morning at eight-thirty. I rose at seven-thirty to start his breakfast, which he ate in the dining room. Often, he asked me to sit and have a cup of coffee to keep him company, and we would chat about nothing — about the nest of blackbirds in the gazebo, or the way the middle C on the parlor piano stuck, or what kind of pickles went best with pork. Sometimes, if he was planning to entertain, we would discuss a menu for cocktails or dinner or after-dinner drinks. He stirred his coffee all the time in an absent way, and the spoon would clink-clink-clink against the cup as we talked.

Once he left the house, I locked the front door and left the key in the lock; this would make it impossible for the major to unlock the door from the outside and come in unexpectedly. This was the time when my friends in the basement could begin their day, taking showers, brewing coffee, listening to BBC war news on the radio while I cleaned the house. They smoked cigarettes as they read the paper and compared the official reports from Berlin with what they heard on the BBC. I returned to the factory every evening to serve dinner, but I always went home before the major.

And when he did return at night and rang the doorbell (I told him I kept the door locked out of nervousness), I opened the door and let him into a house that gave no hint that there were people living in the basement. It almost made me laugh, sometimes, to think of the absurdity and irony of it. Under any other circumstances, it would have been hilarious, because this was the stuff of farce: upstairs, a deaf and snuffling codger, oblivious to the goings-on at his very feet, and below, the hunted stowaways, dining richly off the major's larder. They were like mice in a cheese shop guarded by a sleeping cat. Under the circumstances, however, I never did get all the way to laughter; a grim smile from time to time was all. This was, after all, a capital crime.

So our new life had begun. I got in touch with Helen when I could, and we both waited anxiously for the day when she could come to visit Henry. It came about a month after moving to the villa, when the major announced one evening that he would spend the next day in Lvov. I was thrilled: He would be gone from early morning until late at night. This was the chance I had been waiting for. It meant Helen could visit her husband. It also meant I could go to Janówka and check on my other friends.

That night, I called the farm where Helen lived. Our conversation was in a code we had worked out long before.

"Will you be able to deliver eggs in the morning?" I asked. "Half a dozen will be fine."

"Six?" Helen repeated. "Yes, I'll be there."

And at six the next morning, with the major already on his way to Lvov, Helen drove up in the farm wagon. She was dressed in a long peasant smock and kerchief. I unlocked the door to let her in, and we quickly exchanged clothes. After I tied the kerchief around my head, I let her through the basement door, closing it behind her. I was sorry to miss their reunion, but I had to be on my way. I smiled as the sound of Henry's shout of joy reached me through the door, and the smile remained on my face as I locked the front door behind me and climbed up onto the dorozka.

I had brought food with me, and a small store of medical supplies. The horse's hooves clop-clopped on the pavement, and I kept the kerchief low over my forehead. There were few people out that early in the morning: an old woman sweeping the street with a worn-out, stubbly broom; a man pushing a wheelbarrow loaded with scrap lumber; another man carrying a ladder. Soon I was out in the country, surrounded by green fields and flowers, with swallows darting over the horse's nodding head in search of flies. I took a roundabout route toward Janówka, but it seemed to be no time before the spire of Father Joseph's little church came into view. I promised myself the reward of visiting with the priest on the way home if I had time, and then clucked the horse on, toward the forest.

As always, the stillness of the trees seemed to fall upon me like a mist. Pine needles muffled the horse's hoofbeats as I drove along the shaded road. I looked right and left as we went forward. To one side, a giant tree long since toppled by wind stretched away into the dimness, its dry roots clawing the air. On the other side, a patch of yellow flowers glowed in a spotlight of sun slanting through the trunks.

The horse started as two bearded men emerged from a thicket of blackberries. They approached the wagon, and my heart lifted when I recognized them: Abram Klinger and Hermann Morris.

"Irene!" they called out.

I scrambled down from the dorozka to embrace them. "How on earth did you know I'd be coming today?" I asked, stepping back to look them over. They looked rough and dangerous: forest men.

"There are always people watching this road," Abram told me. "It was our good luck to see you."

"Sometimes it is someone else's bad luck if we see them," Hermann added.

Abram took the horse's bridle and led the wagon off the road, in among the trees. While the horse nosed about among the dry leaves for something green and sweet, we unloaded the dorozka. Abram and Hermann examined my delivery with the eyes of men accustomed to making do.

"Eggs; we'll be glad of those," Abram said, touching one lightly with a dirty finger. He turned over a paper packet of white powder. "Is this aspirin?"

"Yes. I thought you might have use for it," I explained.

Hermann nodded. "Oh, yes. Without doubt. Miriam has a bit of a cold, and this might help."

"Are you all well?" I asked, looking anxiously from one to the other.

"Apart from Miriam, quite well, all things considered," Abram replied. "Summer is good to us. There are berries and mushrooms, and we set snares for rabbits. Sometimes we get fish from the streams."

I had a flash of memories from my days living in the woods with the Polish army, and I shuddered. They might make light of their predicament; I knew how hard their lives had become. And although the land was rich with food now, fall would arrive all too soon, with winter shivering at its heels.

We exchanged news. They were amazed to hear that I was hiding their friends in the cellar of Major Rügemer's house. I tried to play up the farcical elements of the situation, and they allowed themselves a few laughs at the major's expense. They urged me to come deeper into the forest to see their camp, but I was worried about the time.

"Give my love to your wives," I told them, backing the horse and dorozka out onto the road. "I remember you all in my prayers. I'll come as often as I can."

They kissed me again, and told me they would watch out for me every day. I climbed onto the wagon and gathered up the reins, and when I looked again, my friends had disappeared among the trees once more.

The ride home was uneventful. I stopped at the church in the village, but Father Joseph was away, giving last rites to a peasant who had contracted blood poisoning from an accident with his ax. I returned to Ternopol in the hazy light of afternoon, and drew up to the villa.

I sat looking at the door for a few moments, deep in my thoughts. Helen was with her husband; the Hallers and the Bauers had each other; even the Morrises, living as desperate refugees in the forest, had the comfort of family and friends.

And I had never felt so alone. A wave of pity swept over me, and my heart ached for my parents and my sisters. I had sent letters, but I had no idea if they made it to my family; I got none in return — none ever reached me. I tried to conjure up a picture of my childhood friends, of my family engaged in some pantomime game, or giggling as we stumbled over the lyrics to a half-forgotten song. But I only saw myself, as if from above, sitting alone on the seat of the dorozka, and it seemed to me as if the wagon behind stretched on forever, crowded with people, frightened people who depended on me to bring them safely home. I could not drop the reins. And there was no one who could take them from me, not even for a moment.

In My Hands

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: Anchor

- ISBN-10: 0385720327

- ISBN-13: 9780385720328