Excerpt

Excerpt

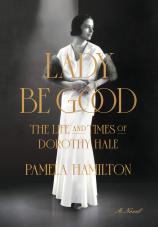

Lady Be Good: The Life and Times of Dorothy Hale

“We have a long history of notable residents here at the Hampshire House,” said Mr. Lachann, the manager of the building. In the darkened office, his desk surrounded by stacks of leather albums filled with photographs, he swelled with pride as he opened one up to show me the people he wished he had known and the parties he didn’t attend. Page after page the images revealed tuxedoed men and their wives, their smiles broad, gowns tasteful, pearls large. Not a mention of Dorothy Hale. The name, of course, would have held no meaning to me then, nor would her picture. More than half a century had passed since she died. I had never heard of her when I signed those papers for an apartment overlooking Central Park and felt a surge of happiness for my incredible good fortune.

If there was some ghostly quality to the place, it was imperceptible to me in those first hours. At twenty-five years of age I was enchanted by the grandeur of the Old New York building, its towering ceilings, intricate Baroque moldings and Art Deco design. It had retained its formality, the uniformed bellman beckoning, “This way, Ms. Harrison,” as he ushered me through the gleaming black-and-white marble lobby. Luciano Pavarotti breezed by wearing a bright-red scarf wrapped around his neck. “To keep the tenor’s throat warm for his performance at Lincoln Center,” I was told. And Rupert Murdoch, exceedingly elegant in a crisp blue suit and Hermès tie, walked past me with a purposeful stride and said nothing as he approached three men standing by the entrance like a diplomatic envoy, then disappeared through the turnstile door into a chauffeured car. The bellman averted his eyes and led me down a long corridor, past Carrera marble busts tucked into niches while Vivaldi’s Four Seasons played softly in the background.

Turning the corner, my pace slowed as the palatial ballroom opened before me, its gracious ambiance brightened by sunlight streaming in from grand glass doors. Well appointed with ornate ivory furnishings and adorned with jade-colored murals, its centerpiece was a chandelier so large and elaborate in design it was fitting for a palace in nineteenth-century France. There was a strange stillness to the room, yet the uproarious banter of bygone days seemed to come alive.

As I drifted toward the courtyard, a scene of vivid detail intruded on my mind and played like a black-and-white silent film: A woman entered the cocktail lounge. It was still bustling in the after hours, clouded with cigar smoke and scented with scotch, the corner tables filled with couples huddling together, and elegant women, a dozen or more, their diamonds sparkling under dim lights, drank champagne with suited men.

The woman walked past the bar, stopped briefly to allow a man to light her cigarette, and went to the far side of the room by the window where she met a man she knew. They spoke. They argued. She left abruptly and ran up the stairwell to the third floor to escape. He followed her. They argued by the window. Now the scene was a blur. She was on a higher floor. She was falling out of a window.

The vision startled me. It was both familiar and profound, like the sudden return of a memory when you catch the scent of a perfume once worn by your mother.

That evening, I searched the history of the building into the wee small hours to find an explanation for the scene I had pictured.

I saw her photograph and the headline “The Suicide of Dorothy Hale,” and my heart stopped beating.

The paper called her “a tragic woman, more beautiful than the young Elizabeth Taylor, whom she resembled,” one of those evident gifts of God polished off by privilege, ease of confidence, and a good measure of grace. At first glance her beauty was striking—fresh-faced and delicate with large eyes, her little black dress cinched at the waist, her hair pinned in a chignon. At second glance, her deep, intelligent eyes were entrancing, still vivid on newspapers yellowed from light and air and lined with age that Fate didn’t offer to her.

“Jilted at age 33, she jumped from the window of her penthouse apartment. . . . She died of a broken heart.” The reporter’s story was sensational—maybe too sensational. I knew because I too was a journalist, one with a keen eye and without clemency for writers who cobbled together accounts with gossip and grand assumptions to profit from others’ pain. But this was the way of rogue newsmen; it was the way it had always been. Dorothy Hale was a curiosity on public view, a thing to write about.

The more I read, the more it became evident the story didn’t seem to add up. One sentence contradicted the next. Quotes were clearly contrived. The reasons for her alleged demise would only be said of a woman, an unsurprising lock, stock, and barrel cliché that was an affront to any female, to be sure. “She died of a broken heart and fading career.” Indeed.

Perhaps more striking and most impossible to overlook was the hunch, the inescapable instinct that soon became unignorable for there was, with little question, more to this romantic tragedy. Fell, jumped, offed—these were the unfortunate possibilities before me. To know the truth, I would have to know how she fared in adversity and the traits that defined her—what was her circumstance, and who did she trust. Only then could I ascertain the cause of her death in the early-morning hours of October 21, 1938. Thus, with the bright surety of a youthful mind and career journalist, it seemed in that split of a second like a perfectly reasonable proposition to learn everything possible about Dorothy Hale.

Reaching for a cigarette from the French antique silver case on my desk, I considered all that I had read, and then, in a moment that would determine the course of too many others, I remembered strolling through the lobby when Mr. Lachann asked his assistant to tend to the attic, clear out the items, and send personal belongings to descendants. I dropped the cigarette onto a tray, took a flashlight from the drawer, and headed for the stairwell. Because what else was I to do? You see how it was an entirely unavoidable course.

I stole away to the attic, climbing step by step and floor by floor until I reached thirty-six, the end of the line. There was no evidence of a route to the pinnacle, but with further exploration I came upon a single door. I opened it a crack, and soon found myself in a twisted purgatory, a maze of narrow passageways with naked bulbs illuminating the walls painted black and crimson red, rusted wires cut and tangled like vines, and more doors revealing other mazes that brought me finally to a stairwell. As I ascended, the thump of my soles echoed in the silence until I reached the top landing. Standing before the final door, I listened to the quiet, and with deep trepidation, I turned the well-worn knob, gave it a vigorous push, and slinked into the room.

Stacked and strewn across the vast wooden floor, abandoned trunks lay worn under a half-century of dust, dated by colored stickers from luxury steamships and European hotels popular with those who could afford the indulgence in the 1930s. From the pitched ceiling reaching two stories high, a faint light came through a small window, casting shadows on a circular steel staircase winding upward to a hatch. It was there, in the little space at the very peak of the Hampshire House, where I discovered three leather trunks embossed with the initials DDH. With a mixed sense of triumph, unease, and extreme curiosity, I lowered myself to the floor, considered which to open, brushed dust from its latches, and raised the lid, releasing a thick, musty smell that seeped into the ghostly air.

Piles of leather-bound notebooks and typewritten pages, the edges browned and tattered with age, had been placed in chronological order, labeled, and tied with white ribbon finished off in a bow like a gift box at Christmas. Touching the fragile paper, it was strange knowing hers was the last hand to hold them so many years before.

The following day, as the sun lowered in the sky, I stepped into the former cocktail lounge on the second floor, a desolate space with an aged mahogany bar and crystal sconces darkened from neglect. I sensed the unsettling aura, the stillness giving way to silent pandemonium of a crowd that could no longer be seen—the nights of posh black-tie parties, laughter and scandal, champagne and cigarettes long since gone.

I had found the clues Dorothy Hale left behind: the note to her attorney, the entries in her journal, and the memoir she never finished. In her last days she noted it would be important for someone to find them, someday in the future, to show that her life had been grand. It seemed she sensed she would become a talebearer’s prey. Surely if she knew she would be referred to as hapless, she would have smiled gently, thought it an idiot’s remark, and twisted a long strand of pearls through her diamond-jeweled fingers. Yes, she would have rolled her eyes upward—astounded at how they had missed the point entirely.

And what else is one to do when presented so unexpectedly with such stupefying intrigue but continue turning the pages back in time, a time when a wave of excess carried the American aristocracy and titled Europeans to grand ships and grander estates for extravagant parties never before seen and never seen thereafter. They stumbled onto the laps of married lovers, champagne spilling onto polished marble floors, betrayal and indecency dressed up in custom-made suits and an air of refinement honed since birth. This was the Jazz Age. The Crazy Years. Les Années Folles, as she often said.

Lady Be Good: The Life and Times of Dorothy Hale

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 298 pages

- Publisher: Koehler Books

- ISBN-10: 1646632729

- ISBN-13: 9781646632725