Excerpt

Excerpt

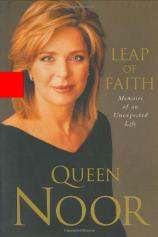

Leap of Faith: Memoirs of an Unexpected Life

Chapter One

First Impressions

I first met my future husband through the lens of a camera. I was standing with my father on the tarmac the airport in Amman, Jordan, when King Hussein strolled over to greet us. Never one to hold back, my father thrust his camera into my hands. "Take my picture with the King," he said. Mortified, I nonetheless dutifully took the photograph, which caught the two men standing side by side, with the King's eldest daughter, Princess Alia, in the background. Afterward my father and the King exchanged a few words. Then King Hussein called his wife, Queen Alia, over to meet us.

It was the winter of 1976, and my father had asked me to join him on a brief visit to Jordan, where he had been invited to attend a ceremony marking the acquisition of the country's first Boeing 747. My father, Najeeb Halaby, a former airline executive and head of the Federal Aviation Administration, was chairman of the International Advisory Board for the Jordanian airline. He was also in Amman laying the groundwork for a pan-Arab aviation university, an ambitious project aimed at reducing the region's dependence on foreign manpower and training. This undertaking, still in its infant stages, was the brainchild of King Hussein, my father, and other aviation dreamers in the Middle East. Since I was at loose ends, having recently completed a job in Tehran, I welcomed an opportunity to travel to Jordan, which I had visited briefly for the first time earlier that year. Another trip to this part of the Middle East would bring me back to the land of my ancestors and, I hoped, reconnect me with the Arab roots of my Halaby family. I distinctly recall my first impressions of Jordan. I had been en route to the United States from Iran, where I was working for a British urban planning firm. From the window of my aircraft, I had found myself spellbound by the serene expanse of desert landscape washed golden by the retreating sun at dusk. I was overwhelmed by an extraordinary sensation of belonging, an almost mystical sense of peace.

It was spring, a magical season in Jordan, when the winter-browned hills and valleys turn green from the winter rains, and wild anemones spring from the earth like red polka dots. Oranges, bananas, strawberries, tomatoes, and lettuces were being sold along the road through the lush fields and orchards of the Jordan River Valley, and city families from the high, cool Amman Plateau were picnicking along the warm shores of the Dead Sea. There was a warmth and joy in everyone and everything I saw, and I was entranced by the delightful harmony of past and present, of sheep grazing in fields and empty lots adjacent to sophisticated office buildings and state-of-the-art hospitals. I remember in particular the sight of students walking in the open fields at the edge of Amman, textbooks in hand, completely absorbed in their studies for the Tawjihi, a general government exam that Jordanians must take in the final year of high school.

I knew from looking at maps how close Jordan was to Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories, but I had not fully understood it until I stood on the Jordanian shore of the Dead Sea and looked across at the ancient city of Jericho on the occupied West Bank. Jordan, in fact, had a longer border with Israel than any other country; it ran some 400 miles from Lake Tiberius or the Sea of Galilee in the north to the Gulf of Aqaba in the south. Despite the enduring beauty of the landscape, World War II, three Arab-Israeli wars, and countless border skirmishes had left Jordan and Israel's cease-fire line—a sacred tract of land where the prophets once walked—riddled with land mines.

My knowledge of Jordan then was limited to what I had read in newspapers or picked up in conversations, but I was aware of King Hussein's unique position in the region. He was a pan-Arabist with a deep understanding of Western culture, a consistent political moderate, and a dedicated member of the Nonaligned Movement. Jordan, I knew, was a linchpin for Middle East peace efforts, strategically located between Israel, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Iraq. While in Jordan, I also learned that the King was a Hashimite—a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, Peace Be Upon Him—and therefore held a special position of respect for Muslims.

The Jordan I visited for the first time in early 1976 was a fascinating blend of modernity and tradition. The Emirate of Transjordan was founded in 1921 and became the independent Hashimite Kingdom of Jordan in 1946. The country had been transformed by King Abdullah, its founder, and then by his grandson, King Hussein, and had steadily developed into a modern state. Having lost its historic access through Palestine to the commercial seaports of the Mediterranean due to the creation of Israel, Jordan had developed Aqaba as a port for traffic on the Red Sea and beyond to the Indian Ocean.

When I first came to know Jordan, the government was initiating an ambitious overhaul of the country's telecommunications. At the time it would take hours to call within Amman, and the capital did not even have international direct-dialing. Birds alighting on the system's copper wires could cut telephone connections, but soon there would be a state-of-the-art network of telephone services linking the country in even its most remote areas.

Smooth new roads had been built, mostly from north to south, to complement the traditional trade routes west through Palestine. You could easily drive, as I did, from Jordan's northern border with Syria all the way to Aqaba on the modern Desert Road. Traveling through the desert I saw nomadic Bedouin tending to their livestock, and children darting in and out of the distinctive black goat-hair tents known as beit esh-sha'ar. As day faded into night, I was transfixed by the rosy golden glow of the setting sun on the rocky hillsides, where herds of sheep looked almost iridescent in the waning light of day.

The Desert Road was the fastest and most direct road to the south, but my favorite route was the scenic Kings' Highway, which followed the ancient trade routes. The Three Wise Men are thought to have traveled at least part of the way to Bethlehem on the Kings' Highway, and Moses used it to lead his people toward Canaan. "We will stay on the Kings' Highway until we are out of your territory," reads Numbers 21:21–22 in the Bible, referring to Moses' request to King Sihon for permission to cross his kingdom, which was denied. Alternating between the two Nikon cameras I wore constantly around my neck, I took photograph after photograph of Mount Nebo, near where Moses is said to be buried, and of the magnificent mosaics I saw in nearby churches, just off the Kings' Highway.

Earlier civilizations kept the dirt track cleared of stones to hasten the passage of donkeys and camel caravans laden with gold and spices, and the Romans paved sections of the Kings' Highway with cobblestones to allow travel by chariot. Evidence of ten thousand years of history is scattered along or near the Kings' Highway, from striking plaster neolithic statues with darkly lined eyes, the oldest representations of the human form, to the Iron Age capital of the Ammonites, Rabbat-Ammon, which forms the nucleus of Jordan's present-day capital, Amman.

The archaeological treasures I saw in Jordan during this early visit were stunning, among them the classical walled city of Jerash in the hills of Gilead, with its colonnaded streets, temples, and theaters. Lakes once covered the eastern desert, where fossilized lions' teeth and elephants' tusks can be found in the sand. On the road to Baghdad loom the 13,000-year-old Islamic "Desert Castles" of the Umayyads—an Islamic dynasty established by the caliph Muawiyah I in 661 A.D.—with their colorful frescoes and mosaics of birds, animals, and fruits, and heated indoor baths.

A few hours to the south lies the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, carved into multicolored sandstone cliffs. Hidden to the Western world for 700 years until Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt stumbled on it in 1812, Petra is entered through a mile-long, narrow Siq, a natural gorge that cuts through the cliffs to emerge into a breathtaking marvel of shrines, temples, and tombs carved into the stone. It has a palette of natural colors and designs that no artist could duplicate, ancient caves and monuments whose floors and walls blaze with swirls of red, blue, yellow, purple, and gold veins of rock.

On that first trip, I explored Amman on foot. Shepherds crossed the downtown streets with their flocks, herding them from one grassy area to another. They were such an ordinary part of life in Amman that no one honked or lost their patience waiting for the streets to clear; animals and their minders had the right of way. I wandered through the marketplace admiring the beautiful inlaid mother-of-pearl objects—frames, chests, and backgammon boards—as well as the cobalt blue, green, and amber vases known as Hebron glass.

Amman looked classically Mediterranean with its white limestone buildings and villas ranging over and beyond the seven fabled hills that Roman general Ptolemy II Philadelphus had conquered in the third century B.C. In my room in the Inter-Continental Hotel, situated on a hill between two valleys, I lay awake each morning in the predawn stillness, listening to the call to early morning prayers, Al Fajr. I was completely captivated by the rhythmic sound of the muezzin calling to the faithful as it echoed off the surrounding hills. Jordan's capital was peaceful and calm, so different from the growing restiveness I had witnessed in the last months of my job in Tehran.

On that fateful day when my father introduced me to King Hussein on the tarmac, a dense cluster of people surrounded the monarch: members of his family, the Royal Court, and government officials, including the CEO of the Jordanian airline, Ali Ghandour, an old friend of my father who had invited us to the ceremony. A lifelong aviator, the King was celebrating an exciting step forward for his beloved airline, which he considered a vital Jordanian link to the world. No doubt he simply longed to head for the cockpit of the country's first 747 and take off. Instead he was surrounded by courtiers, officials, guards, and family members. It was as if an invisible string were holding them all together; when the King moved, the entire group would sway with him.

As I watched, I was struck by the way the King never lost his composure or his smile, despite the overwhelming noise and confusion. For many years I was reminded of that day at the airport by the photograph my father had asked me to take. During my engagement and after I married, I kept it in my office, still in the photo shop's simple paper frame. Sadly, it was lost more than a decade ago, when I asked to have a copy made. I keep hoping that it will fall out of a book or show up in a desk drawer; it is not often that one has a memento of the very first moments spent with someone who would become the most precious part of one's life.

That short stay in Jordan ended with lunch at the King's seaside retreat in Aqaba, which had an appealing simplicity. Instead of living in an imposing vacation palace, the King and his family resided in a relatively modest beach house facing the sea; guests and other family members were housed in a series of small, double-suite bungalows that made up the rest of the royal compound.

The King was traveling at the time but had asked Ali Ghandour to "take my good friend Najeeb to lunch in Aqaba." Over the mezzah, an assortment of appetizers including tabouleh, hummus, and marinated vegetables, the conversation veered quickly to politics—to Lebanon and its ongoing bloody civil war. I listened intently, asking many questions, fascinated by the complex political events of the region.

Aqaba was a lovely spot, but our sojourn in Jordan was nearing its end. Soon I would be back in New York, hunting for a job in journalism. I never imagined that I would be returning to Jordan just three months later, nor did I have any inkling of how fateful that return would be. Perhaps I should have taken more seriously a curious prediction made on one of my last evenings in Tehran, just a few months earlier. At the end of a farewell dinner at a restaurant in the city center, an acquaintance at the table had told my fortune in the traditional Middle Eastern way, by reading my coffee cup. He swirled the thick grounds, turned over the cup, flipped it back, and studied the patterns within. "You will return to Arabia," he had predicted. "And you will marry someone highborn, an aristocrat from the land of your ancestors."

Chapter Two

Roots

I first learned the history of my family when I was six years old in Santa Monica, California. One day, in my parents' bedroom overlooking the ocean, my mother told me about my Swedish and European ancestry on her side of the family and my Arab roots on my father's. I remember sitting there alone after our conversation, staring out the window at the limitless horizon of the ocean. It was as if my world had suddenly expanded. Not only did I have a new sense of identity; I felt connected for the first time to a larger family and a wider world. To my mother's long-standing frustration, I was most intrigued by my Arab roots, but how could my mother's hardworking, hardy forebears compete in my imagination with the dashing brothers Halaby?

My Arab grandfather, Najeeb, and his older brother, Habib, were only twelve and fourteen when they had sailed steerage from Beirut to Ellis Island with their mother, Almas, and younger siblings. They hailed from the Syrian city of Halab, or Aleppo, a great cultural capital and center of learning in the Arab world. My grandfather lived very briefly in the scenic riverside village of Zahle, Lebanon, before joining the family in Beirut for its voyage to the New World. Stored in their oversize carpetbags were oriental rugs, damask fabric, copperware, and jewelry—fine wares from the old country to sell and trade while they adjusted to a new life. The Halaby boys barely spoke English and had no contacts, but they turned out to be as shrewd as they were charming. They took their carpetbags to the summer resort village of Bar Harbor, Maine, where Najeeb met and beguiled Frances Cleveland, the pretty young wife of President Grover Cleveland. The letters of introduction the First Lady gave the young Arab ensured the brothers' initial success.

Habib stayed in New York to work in the import-export business, while Najeeb moved on to Texas in pursuit of oil and cotton money. Darkly handsome, gallant, and exotic in socially conservative Dallas, Najeeb met and married interior decorator Laura Wilkins, the daughter of a local rancher, in 1914. Together they founded Halaby Galleries, which combined his import-export skills with her love of art and decorating. Their business catered to the fashionably rich of Dallas, Houston, and Fort Worth. It was such a huge success that when Stanley Marcus and his partner, Al Neiman, doubled the size of their department store in downtown Dallas in the mid- 1200s, they invited Najeeb and Laura Halaby to rent the top two floors to house the Halaby Galleries. More than half a century ago, that farsighted troika of Neiman, Marcus, and Halaby created a center for the luxury trade in downtown Dallas.

Perhaps this entrepreneurial instinct was a family trait. Camile, Habib and Najeeb's younger brother, was equally enterprising, though in a less conventional way. While Habib and Najeeb were making their way in the United States, Camile decided to leave Brooklyn for South America. His mother—my father's grandmother, Almas, who barely spoke English—had seen an advertisement in The New York Times offering a reward to the person who recovered a sunken dredge full of gold from the Atrato River in the tropical jungles of a remote country called Colombia. The Choco Pacific Gold Mine Company was in dire financial straits due to the accident, and its only hope was to salvage the gold. Speaking not a word of Spanish, Camile arrived in Colombia and gamely made his way into one of the least hospitable rain forests in the world, crossing from the coastal city of Barranquilla through the jungles of the Darien Peninsula. He ended up rescuing the dredge, gaining the reward, and traveling across the Andes to Medellín, where he won the hand of a local beauty. He settled in Colombia and became a successful manufacturer's agent for textile companies, an owner of several textile mills, and co-owner of a boiler factory. He and his family became prominent in Medellín. (Indeed, they have felt the negative repercussions of that prominence quite dramatically; several family members have been kidnapped for ransom, and two were killed by warring Colombian terrorist factions.)

My father, born in Dallas in 1915, was an only child. My grandmother doted on him, and he wanted for nothing. He attended private school and lived in a beautifully appointed house that doubled as a customer showcase for Halaby Galleries. My grandfather, to his credit, never Americanized his family name, as so many immigrants did. He was accepted, nonetheless, and was even invited to join the Dallas Athletic Club despite the many restrictions they placed against the ethnic groups that were flocking to the New World. His only concession to his adopted country, besides taking the nickname Ned, was to allow his wife to convert him from the Greek Orthodoxy of his childhood to the Christian Science faith. From that time onward, my grandfather followed the teachings of Mary Baker Eddy, who emphasized healing through spiritual means. He and my grandmother did not consult doctors and eschewed the use of medicine, which may have contributed to his death at an early age. After waiting for faith to cure what was thought to be a case of strep throat, Najeeb senior was quite weak when he finally went into the hospital, where he developed an infection and died. My father, his son, was only twelve years old.

After her husband's untimely death, Laura Halaby, my paternal grandmother, sold the Halaby Galleries and moved to California. She remarried not long after—this time to an affluent Frenchman from New Orleans. The marriage lasted six or seven years, apparently strained by relations between my father and his stepfather. At least some of the disaffection stemmed from the attention Laura heaped on her son, which made her new husband quite jealous. Indeed, Laura's boy, "Jeeb," did much to make her proud. My father excelled at whatever he tried and lived life with great gusto. He attended Stanford University, where he was captain of the golf team, then went on to Yale Law School. Once he graduated, he became a pioneering aviator, flying the P-38 twin-engine fighters, the Hudson bomber, and the Lockheed Lodestar transport during World War II as a test pilot for Lockheed aviation. As a navy pilot in the Carrier Fighter Test Branch, he would fly more than fifty different types of aircraft, including the first American-built jet.

My father had the temperament so necessary to a test pilot. He was bold, confident in his technical skills, focused, and a risk taker, as well as possessing an aviator's broad perspective and inherent optimism—personality traits he would share with my future husband. One test of my father's character occurred during his stint in the navy, when it fell to him to coax the first primitive jet, the YP-59, up to 46,900 feet, the highest altitude any plane had ever reached. He was so excited to have broken the altitude record that he forgot to check the fuel gauges. Both engines flamed out at 12,000 feet, leaving the plane with no power, no radio, and no way to electronically lower the flaps or landing gear. He had to hand-crank the gear down—exactly 127 turns, he noted later—succeeding with seconds to spare at 100 feet over the runway. He then somehow glided the plane in, for what is known as a deadstick landing.

Najeeb Halaby met my mother, Doris Carlquist, at a Thanksgiving party in Washington, D.C., in 1945, a few months after the war ended. My mother was tall and blonde, of Swedish descent, and came, as my father did, from the West Coast. They seemed perfectly suited. Both had come east to join the war effort, he as a test pilot, she as an administrative assistant first in the Office of Price Administration, then in the State Department's German- Austrian Occupied Affairs Branch. They quickly discovered they shared an interest in politics. "For the first time I had found a quick and witty girl who enjoyed this give-and-take debating as much as I did," Najeeb observed later. And they were both idealistic. "Like me, she had stars in her eyes about peace and international understanding," he said. They were married three months later.

Married life must have been difficult for my mother. My father was an unapologetic workaholic and was rarely at home. After the war he had joined the Office of Research and Intelligence, a new branch of the State Department. He spent the second summer of their marriage in Saudi Arabia, as civil aviation adviser to King Saud Bin Abdul Aziz. When Najeeb returned to Washington, he successfully urged the State Department to increase American military aid and technical assistance to the oil-rich nation.

Other governmental departments were being revamped after the war, including the military. When the Defense Department came into being in 1947, unifying the various competitive military branches, my father left the State Department for the Pentagon to work for the first Secretary of Defense, James Forrestal. After Forrestal's tenure came to an end, my father continued at Defense, helping to organize NATO under Truman and becoming deputy assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs under President Eisenhower. By the time I was born in August 1951, however, he was weary of government service. Money was becoming an issue, and he began to eye the private sector. He met Laurance Rockefeller at a naval reserve officers' dinner in 1953. The largest shareholder in Eastern Airlines, Rockefeller offered my father a job, and that year we moved to New York.

My childhood memories begin around this time. My brother, Christian, was born in 1953, and my sister, Alexa, in 1955. My nursery school was a few blocks from our apartment on East 73rd Street in Manhattan. In that dark, crowded, overheated schoolroom, I was agonizingly torn between competing instincts to join in or maintain a solitary independence from the group. I can never remember not being shy. As a child, I would make myself scarce when my parents' guests would come to our house and I knew I would be expected to exchange pleasantries with them. I had a small number of friends, but we were close, which was what mattered to me.

We moved often during my childhood, and the constant change reinforced my natural reserve. Every few years I would have to adjust to a new, strange home and new friends, as well as new schools, neighborhoods, and cities. Time and again I would find myself on the outside looking in—watching, studying, learning—having to familiarize myself with unfamiliar people and communities.

My father viewed me as "aloof," and my mother, concerned about what she considered my loner temperament, turned to a child psychologist for advice. The psychologist told my mother I would grow out of it, but in truth I never did. To this day, I am most comfortable when a conversation has an intellectual focus. Perhaps this helps explain why I have always felt particularly inept at and impatient with small talk, intrigues, and gossip.

Part of this social awkwardness no doubt stems from a sense of inadequacy, rooted in considerable part in my relationship with my father. He sought perfection and never seemed satisfied. I felt I could never measure up, and as I was the eldest, his expectations for me were the most pronounced. I will never forget one incident in grade school concerning my eyesight, which was extremely poor, though no vision problem had yet been diagnosed. When I could not see the writing on my classroom chalkboard even from the first row, my mother took me to an optician. Back home after the visit, my mother explained to my father how truly weak my sight was. He did not believe it at first—or did not want to believe it. He held up a copy of Time magazine and asked me to read it. He held it quite close, but I could not read even the headlines. He still refused to believe I needed eyeglasses. How could one of his children be so flawed?

My father learned a great deal about the aviation business working for the Rockefeller brothers, immersing himself in the corporate financing of airlines and the municipal funding of airports, setting up a task force to reorganize and modernize the country's rapidly growing airways and airport systems. When political infighting kept him from being appointed head of the Civil Aeronautics Association, he decided to leave the Rockefellers. Shortly thereafter he became executive vice president of an electronic subsystems manufacturer, Servo-Mechanisms, Inc., with offices in Long Island and Los Angeles.

I was five when we moved back to California, supposedly for the summer. My mother says the move was particularly traumatic for me, but I suspect those may have been her own feelings about leaving the East Coast, as I have only happy memories of those years. I loved being outdoors, and I learned to swim in the pool of that first house we rented in Brentwood. The house, which had belonged to the actress Angela Lansbury, had a wonderful garden full of orange and lemon trees. To this day I remember its rich citrus smells, the exuberant bougainvillea vines, and the stately palm trees.

We moved to another house in the fall, and then a few months later to an enchanting old Victorian situated on the edge of a Santa Monica blu. overlooking the Pacific. With an expansive, tumbledown garden bordered at the end by a row of dilapidated pigeon cages, it was a wonderful house to grow up in: eccentric and full of character, like an old Maine summer hotel. It had, with its high ceilings, an atrium filled with plants, a billiard room, a porch with a huge swing, and a spacious, romantic attic in which my father, in a burst of domestic energy, assembled a puppet theater swathed in tiny lights, where we spent many happy hours entertaining family and friends.

I contentedly played alone in a vacant lot next to the house, digging in the soil and collecting rocks. I loved to read books under my favorite magnolia tree. It was here, in a little alley near the house, that my father taught me to ride a bicycle. I had to learn quickly, as he had little patience. Perhaps the house's most winning attribute was its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, which I could hear so clearly as it thundered outside my bedroom window, lulling me to sleep, a constant, comforting companion. My preferred refuge was the ocean. I spent hours riding the waves o. Santa Monica, often with a favorite raft. The ocean was both freedom and challenge for me, and I was blissfully happy just being out there on my own.

Whenever we moved, my paternal grandmother, Laura, would move with us, in order to be close to her son and his family. Opinionated and flamboyant, she was an integral part of my early memories of Santa Monica. Often, after classes at the Westlake School, I would walk the short distance to her home and immerse myself in her world, at once artistic and unconventional. With her Art Deco jewelry, loose flowing dresses, and intriguing art and memorabilia, she was the most original person I had ever met. She was also a dedicated Christian Scientist, and I was influenced by her to believe in the power of positive thinking—that an optimistic outlook in life can create positive outcomes, not just for oneself, but for others, too. I was still very young, nine or ten at the time, but the two of us would engage in long philosophical discussions about how to live a meaningful and worthy life.

As the oldest child I had to find my own way; nearer in age to each other, my brother and sister shared a room and seemed very close and companionable. I was sleepless for what seemed like hours and hours every night, intensely conscious of my isolation, the only creature still stirring in a peacefully slumbering house. Restlessness drew me to my father's library, where I would spend hours poring through his eclectic collection of books. I particularly remember Khalil Gibran and Nevil Shute, the classics, and the infinitely fascinating Encyclopaedia Britannica. I would flip through copies of National Geographic and gaze longingly at the globe that helped me chart my parents' international trips.

One day in Santa Monica I decided to run away from home, certain that at age nine I was now perfectly capable of looking after myself in the larger world. I dragged a sheet o. my bed and piled all my most precious possessions into it, at the last minute adding my entire collection of Nancy Drew books and an alarm clock to the mix. After hauling this unwieldy cargo down the long winding staircase, across the entrance hall, and out the front door, I paused on the front porch to consider my options. It was a balmy summer evening, with the ocean undulating in the distance while the bright ball of the sun gradually dropped beyond the horizon. I so loved that view that I was lulled into a reverie. Suddenly it was dark. I never made it any farther. My sister loves to tease me about my failed odyssey, saying that several years later when she attempted the same escape she at least made it beyond the front porch and across the street.

We left California when I was ten, to return to Washington, D.C. John F. Kennedy had been elected President in 1960, and my father had been approached soon afterward by two of his former colleagues at Yale Law School—Sargent Shriver, Kennedy's brother-in-law, and Adam Yarmolinsky, a Kennedy talent scout—to take over the Federal Aviation Administration. My father was flattered but reluctant to accept the government post. He had left Servo-Mechanisms to start his own technology company in Los Angeles and was also practicing law. He was finally making good money and was not in a rush to return to the relative penury of public service. It took a private meeting in Washington with the President-elect, the day before he was inaugurated on January 20, 1961, to convince my father to accept the stewardship of the FAA and to become Kennedy's presidential aviation adviser.

My brother, sister, and I were not at President Kennedy's inauguration on that freezing, snowy day in Washington. We watched it on television in sunny California and saw our parents seated close behind the windblown podium where Kennedy took the oath of office. Nor were we in Washington for my father's Senate confirmation hearings, or for his swearing-in ceremony in the Oval Office on March 3 as only the second administrator of the FAA. He could not afford to bring us to Washington. Overnight his income had dropped by two-thirds, and the federal government did not contribute to the cost of relocation. So, to my great relief, we remained at home in California for the rest of the school year and the summer.

My first inkling of my father's prominence in the Kennedy administration came at a farewell party for him at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. A helicopter was sent to take us to the lawn at the Ambassador, then on to see my father preside over the ceremonial opening of the new Los Angeles International Airport. I loved my first helicopter ride, which was fortuitous given the integral role helicopters would play in my future. I was less enthusiastic about the ceremonial role I had to play at the airport. It had been decided that I would have the honor of teaming up with Vice President Lyndon Johnson onstage at the airport to unveil the commemorative plaque. I was almost paralyzed by stage fright, but I did it and was complimented afterward by a sweetly supportive Lady Bird Johnson.

Once in Washington I had further adjustments to make. I had coasted through school in California, but now I was finding the educational system much more rigorous. I was also tall for my age, scrawny and awkward, and dependent on Coke-bottle-thick glasses. I missed California, the sunshine, the ocean, the pungent smell of fresh citrus, the majestic, quirky character of the palms, and the freedom of being outdoors all year round.

Fortunately, my grandmother's home, a farm in nearby Centreville, Virginia, provided a peaceful retreat. I already loved horses and spent hours exploring the countryside on a small pony with my grandmother's German shepherd tagging along behind. It was not far from my grandmother's property that I had my first startling exposure to poverty when I came upon a cluster of dilapidated shacks on the edge of a farming community. I felt absolute shock, fear, and then utter helplessness and guilt as I was confronted by the blank, hopeless stares of migrant children and their families seeking shade from the pitiless noonday sun.

As we children reached adolescence my parents insisted on sending us to private schools. This decision created a further financial burden, but my parents were adamant, and I was sent to the National Cathedral School for Girls. A number of my classmates at NCS were also daughters of transplanted members of the Kennedy administration, and we naturally gravitated to each other, newcomers all. Grace Vance, whose father, Cyrus, the new Secretary of the Army, had attended Yale Law School with my father, became a close friend, as did Carinthia West, whose father, the distinguished general Sir Michael West, was the British representative to NATO in Washington, and Mo Orrick, whose father was an assistant attorney general. Like young girls everywhere we were captivated by the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and other rock and roll groups, but some of us, because of our parents, were even more interested in national politics and the world scene.

The Peace Corps topped the list of career goals in my diary of those Washington years, and there were times, in spite of my friendships at NCS, when I longed to leave the privileged environment of my private girls school for a less rarefied milieu. I urged my parents to allow me to attend Western High, a public school in Washington where I knew I would not be so insulated from the social and economic realities of the world, but to no avail.

I became aware of racism for the first time. Federal laws prohibited racial discrimination in public schools and universities, but several southern states were either ignoring or defying those laws. The new Kennedy administration's commitment to social justice encouraged civil rights leaders, among them Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to press for the enforcement of existing legislation and for sweeping new laws to eradicate racial discrimination once and for all. The powerful television images of African Americans—or Negroes, as they were called then—were having a profound impact on me and on many of my classmates. We saw policemen beating protesters for peacefully trying to assert their legal right to vote, to attend school, or even to sit in the front section of a public bus.

I will never forget watching the television news with my grandmother in the fall of 1962 when James Meredith, a young black man, tried to enroll at the University of Mississippi. He had to be escorted through a jeering crowd and up the steps by federal agents and, even so, was turned away time and again by police and state officials. Martin Luther King came on the screen, commenting on the mistreatment of Meredith. Filled with admiration, I said, "Isn't he wonderful?" My grandmother agreed, but it quickly became apparent that she was praising George Wallace, the racist governor of Alabama, who had spoken about the event a few minutes earlier, and the realization triggered an excruciating argument. I stormed o. to my room and buried myself in a book until I left the next day. I thought that I would never be able to forgive her, and in some ways our relationship was never quite the same.

A small group of my friends and I supported the civil rights movement through the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which had been founded in 1960 to coordinate student "sit-ins" at segregated lunch counters throughout the South to force their integration. The sit-ins had started informally when four black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, had gone to an F.W. Woolworth store to buy school supplies; when they sat down at the store's segregated lunch counter to eat, they were refused service. More black students returned to Woolworth's the next day, accompanied by a reporter, and soon sit-ins were launched at segregated lunch counters all over the South. By the time I joined SNCC in 1961, the student movement had grown to more than 70,000 participants and had broadened its segregated targets to include public parks, public rest rooms, movie theaters, libraries—anyplace where people assembled. We wore our SNCC pins with pride, marched, and joined protests, adding our youthful voices to the larger call to action. We sang "We Shall Overcome," and we meant it. Images of police dogs attacking children and powerful water cannons knocking them o. their feet were viewed constantly on television sets across the country, and before long President Kennedy announced that he was sending sweeping civil rights legislation to Congress. We were so young, yet we felt responsible for contributing our voices and energies to the call for social justice. I vividly remember the massive civil rights march in Washington and the rally at the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963, five days after my twelfth birthday. I could not understand why everyone in the city was not marching that day, or why they were not as inspired by Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech as I was.

Life in Washington was not just about politics. Horseback riding was my other passion, and, instinctively perhaps, I formed a special bond with a magnificent Arabian stallion, Blackjack. I felt particularly capable and at peace with the world when I was on horseback, and I competed whenever possible in regional equestrian events. When my instructor suggested I was ready to compete nationally, I was filled with pride and determined to commit completely to the sport.

I also loved singing. My chorus teacher encouraged me to take private lessons, giving me the impression that I had a special talent, but in retrospect I realize that her suggestion was probably rooted in a desire to save her ears and the reputation of our school choir. For financial reasons my parents said no to voice and violin lessons, which my mother wisely anticipated would torture the entire household.

I discovered the pleasures of flying as well. A few times during those years my father took me with him on working visits to small-town airports around the country in a small plane. He let me take over the plane's basic navigational controls and work the radio, acting as his copilot. During those rare moments my father and I were in perfect harmony.

My father was rarely home during the four years he ran the FAA, and when he was home he was often distracted. One of my most significant memories was of a conversation we had one sunny Sunday morning in the small garden of our Washington home, when my father seemed particularly distressed. I asked what was troubling him, and he explained that he was struggling under a terrible burden of debt and yet was happier and more fulfilled in public service than in any more lucrative career. I remember being both frightened by his uncharacteristic vulnerability and extremely proud of him. The conversation, perhaps our first adult exchange, had a profound impact on my thinking, my dreams for the future, and my appreciation for sacrifices made for a larger purpose.

We were all raised to be independent, perhaps to a fault. My father now says, looking back, that he and my mother probably encouraged us to be too individualistic, islands unto ourselves rather than part of a whole. Perhaps we reflected the growing and irreparable gulf that was dividing our parents. The constant tension between them permeated the household. My father says now that he and my mother differed in "terms of faith and intellectual beliefs and philosophy," and he has questioned whether they should have had children at all. But they did, and from an early age we all had to deal with the palpable conflict between them. I protected myself as much as possible from the turbulence in their marriage, trying very hard to distance myself from them emotionally.

My father also attributed the seeds of marital disharmony to the very different life experiences my parents had as children, which led to their different expectations as adults. My father considered himself far better educated than my mother, whose father had been in the brokerage business in Spokane, Washington, in 1929. when the stock market crashed, and he had never recovered. Her mother, May Ethel Ackroyd Carlquist, had died when Doris was fifteen. A few years later, she was forced to drop out of college for financial reasons, and instead of living with her father, my mother was passed from relative to relative. Her father had encouraged Doris and her two siblings to be self-sufficient, and my mother had strong professional goals, yet when she married my father she gave up her job, as was customary then for married women. Once her children were out of grade school she dedicated herself to community service, working for a New York settlement house in East Harlem. She also volunteered with public television as well as with a number of organizations promoting U.S.–Arab relations, social welfare in the Middle East, and support for Palestinian refugees, commitments she honors to this day.

For all the tension in my parents' marriage, my mother was very fond of the Arab side of the family. Though she had never met Najeeb, Sr., she did meet his brother, Camile, who sent her white orchids from his farm in Colombia when she married my father. (I would carry orchids from Camile's farm at my wedding as well.) My mother wanted to name me Camille in his honor, but my great-uncle protested. Like many immigrants to the Americas, he felt pressure to assimilate as thoroughly as possible and to de-emphasize his Arab roots. He wanted my parents to name me Mary Jane. They compromised by giving me a name that I never identified with, Lisa. Once I heard that story, I always thought of myself as Camille.

As much as I loved and admired my father, we had an extremely difficult relationship. I realized at a fairly early age that the frustrations my father took out on his family stemmed from the impossible standards he set for himself. He had clear goals at the FAA, but he was plagued by partisan infighting as he tried to achieve them. He was also beset with financial problems, a troubled marriage, and the added pressure of being an oddity in WASP Washington. I remember a quiz in one of the local papers asking, "What is a Najeeb Elias Halaby: animal, vegetable, or mineral?"

My father's dissatisfaction was a reflection of his unrelenting drive to prove himself. During one particularly intense episode at home I looked up at his face, glowing with rage, and I realized with absolute clarity: This does not have to do with me; this has to do with him. "He is so frustrated that he needs to get it out of his system," I thought to myself. My sister developed a strategy of accommodation, whereas I had a completely different approach: "Take me or leave me as I am." Although I may have seemed defi- ant, I wanted desperately to be accepted for who I was, on my own merit.

In an interview many years later, I would describe my family as a typical late-twentieth-century, moderately dysfunctional American family, and I believed that to be an honest and diplomatic description. However, my mother was very upset when she read those words. Maintaining the myth of the ideal family was very important to her generation, which is precisely what kept my parents together for far longer than made any sense. I remember as a teenager begging them to divorce for their own sakes—not what most children want their parents to do—but they remained miserably imprisoned by convention until they finally dissolved their marriage in 1974. Ironically, their divorce eventually freed them to rediscover what they had initially so appreciated in each other, and they have become great friends and confidants over the years.

On November 22, 1963, while crossing Woodley Road with my classmates on our way to the athletic field, I heard a devastating report from Dallas, Texas, on the crossing guard's radio. President Kennedy's motorcade had come under fire, and there were concerns that the occupants of his car might have been hit. The news moved like wildfire through the school. When the National Cathedral's bells began to toll their tragic message later in the day, we were devastated. It was inconceivable that our dashing young President could have been in harm's way. The Secret Service whisked away Vice President Johnson's daughters, and the daughters of Kennedy appointees were called into the headmistress's office to be reassured.

President Kennedy's death shattered my world. My father, indeed everyone I knew, was inspired by the President's ideals, his energy, and his ability to attract exceptional talent. His assassination was a crushing blow, especially after such a heady period of optimism and hope. My father continued to head the FAA under the new President, Lyndon Johnson, who had many good qualities—I especially admired his ardent defense of civil rights and his commitment to wage the "War Against Poverty"—but his forcefulness was less appealing when he consistently rebuffed my father's many requests to return to the private sector. My father finally prevailed and moved us to New York in 1965. Heavily in debt after four years at the FAA, he accepted an offer from Juan Trippe, the founder and CEO of Pan American World Airways, to take over Pan Am.

Another new school. Another new environment. I was fourteen and miserable. Moving to New York meant I was deprived of my treasured horseback riding. On top of all this disappointment and insecurity, my first months in the city were haunted by an unusual menace—a young man, an American University student once employed by my mother in Washington as a part-time babysitter, was harassing me with a series of disturbing letters. I was terrified. He wrote that he was watching me, that he was going to visit me and take me away. In those first months in New York, I was certain he was stalking me. I was afraid to leave the apartment building, and when I did, I felt even worse. I finally confided in my mother, who alerted the authorities. The young man was eventually institutionalized, but it would be some time before I could relax.

It was around this time that I went on a classical studies tour of Greece. My Mediterranean Arab instincts surfaced in the marketplaces, where I learned the art of bargaining over every price. On my return to New York, I reflexively continued to use the same approach when making a purchase at Bloomingdale's, to the clerk's total befuddlement. It was not easy to suppress the Halaby brothers' entrepreneurial genes.

In New York my parents insisted on sending me to the one school we visited that I had said I did not want to attend: Chapin, an elite private school for girls. My mother and my father were concerned about negative peer pressure and wanted to protect me from the social upheaval of the times. I had no plans to become a flower child and run away to San Francisco, but I was increasingly vocal about my opposition to America's military involvement in Vietnam.

From the beginning Vietnam was different from other wars: It was televised, bringing the wrenching images of war into our student dormitories and people's living rooms; also, its goals were ambiguous, offering little justi- fication, many of us thought, for becoming involved in a civil war thousands of miles away in Southeast Asia. Americans divided quickly into two camps: hawks, who supported military action and saw it as essential to limiting the spread of Communism, and doves, who supported the withdrawal of U. S. troops from Vietnam. Indeed, many students felt U. S. intervention into Vietnam's internal affairs was immoral in light of the corruption and unpopularity of the Vietnamese government; others were protesting the draft, the use of violence against civilians, and the mounting body count of American soldiers. Yet the military buildup continued. By the end of 1965, the nearly continuous bombing raids over North Vietnam were under way, and there were more than 200,000 U. S. troops in Vietnam.

It was a heady time to be young in America, but not at my school in New York. The world was held at arm's length at Chapin, with no student involvement in the debate over Vietnam or the civil rights movement or, indeed, anything that smacked of dissent. Instead, there were rules and regulations about everything, starting with the school uniform. Chapin girls had only just stopped wearing gloves to school but were still required to wear hats, and in the era of miniskirts, the skirts of our uniforms had to touch the floor when we kneeled. After the stimulating and politically charged environment my friends and I had enjoyed in Washington, Chapin felt like a straitjacket. I deeply resented my parents' unilateral decision to send me there.

Nor was my independent spirit appreciated by school authorities. My election to class office was vetoed by the Chapin administration because I was considered "apathetic and negligent." They might have felt I posed a threat to their well-ordered, meticulously controlled environment. Perhaps I did. Being viewed as a less-than-desirable Chapin student was a distinction I shared with a far more illustrious Chapin rebel, Jacqueline Bouvier, who had attended some twenty years earlier.

To the school's credit, it offered a community service program tutoring non-English-speaking students in a public school in Harlem, and I volunteered to serve. It was a humbling experience. Initially I was frustrated by my inability to make any meaningful progress with the students, many of whom had serious learning disabilities and needed far more support than I or anyone available to them would ever be able to provide. I eventually made some headway, but the most important lesson I took away from the experience was just how difficult it is to break the vicious cycle of ignorance and poverty. Years later I chose to focus my senior architecture and urban planning thesis at Princeton on a community redevelopment scheme in Harlem.

While I struggled at school, my father was having his own difficulties at Pan Am. Juan Trippe was very farsighted—he was the first airline executive to add Boeing 707 and 747 jets to his fleet—but he was also grandiose. He ordered no fewer than twenty-five of the first 747s, which were too heavy for their engines, and approved several extravagantly expensive construction projects. Moreover, for all his promises that he would step aside and make my father CEO of the airline, Trippe continued to rule the company for another four years. When he finally retired, he made my father president but handed the chairmanship of the financially strapped airline to another man.

For all my father's challenges as second in command at Pan Am, there were substantial benefits to us. Since we traveled Pan Am routes for free, during holidays we went wherever Pan Am flew; skiing was more economical for us in Austria or Switzerland, as was studying the Greek language in Greece and French in France. That part of our family life was heaven, but the tension at home was becoming more pronounced. Looking back however, I realize that circumstances at home—my father's unrelenting perfectionism and my mother's courageous if painful struggle for family peace—strengthened me and taught me self-reliance. And I would draw inspiration from their dedication to public service, for the rest of my life.

After years of lobbying my parents to attend boarding school, I finally succeeded in attending Concord Academy, in Concord, Massachusetts, for my remaining two years of high school. The school was one of the most academically prestigious in the country, and I had been particularly impressed in a meeting with the headmaster when he explained that students were disciplined for missing or being late to classes or meals by having to chop the wood that helped heat the dorms in winter—a healthy contrast, I thought, with Chapin's controlling atmosphere. I felt very fortunate to be at Concord Academy. My classmates were a brilliant group of strong, motivated young women. Academic life was extremely stimulating, and expectations were high, but more important to me, the school placed a high premium on individualism and personal responsibility.

It was on a whim that I applied to Princeton University in my senior year at Concord. For years I had planned to return to the West Coast for university, and I particularly loved the campus at Stanford University. Princeton was debating opening its doors to women for the first time in its 222-year history and had indicated they might consider applications for the class of 1973. My college adviser was very enthusiastic and urged me to apply. I did, for a lark; I was going to Stanford if they accepted me. Princeton, traditional and conservative, did not fit my notion of an ideal university, especially during this period of social change and political turmoil.

In the hot competition for places at top-rated universities I did not feel particularly distinguished, although I had good test scores, played several varsity sports, and was captain of my field hockey team. Compared to my talented classmates I was unremarkable, so when my letter of acceptance arrived from Stanford, I was thrilled. I was also one of 150 women, along with my good friend and classmate Marion Freeman, whom Princeton accepted for its historic first coed class. I was suddenly torn. Part of me was drawn to the unprecedented Princeton challenge, but I was also longing to return to California. I agonized until the last minute of the deadline for postmarking our replies. I stood at a mailbox on a deserted New York City street weighing my options and finally mailed my acceptance to New Jersey, thinking I could always transfer after two experimental years.

That fall, Princeton's first class of women arrived on campus with little sense of what to expect. We found ourselves isolated in a dormitory, Pyne Hall, on the edge of the campus. We were definitely in an awkward situation, one woman to every twenty-two men, males whose previous experience with women on campus was as weekend attractions. We were not dates; we were not made up; we were just going to class at eight in the morning.

Marion and I would room next to each other during our sophomore year and become very close friends. We remain so to this day. Unfortunately, the reserve I had acquired in nursery school to cope with my social awkwardness led to all sorts of misconceptions. One upperclassman told me that at first he had thought of me as a "New York snob," while another labeled me "haughty" and an "ice princess." It did not help that, in a flurry of publicity, my father was finally named the new CEO and president of Pan Am soon after the fall term began, further cementing my "unapproachable" image. One day I was confronted by a couple of upperclassmen who taunted me about my Arab background, one more reason I spent so many Saturday nights of my freshman year alone, reading in my room.

In the midst of all this, my mother began calling me, desperately trying to persuade me to make my society debut in New York that winter. I found the whole idea absurd. The archaic "coming out" party tradition to introduce young women to society, and thus, presumably, to establish their eligibility for marriage, was anathema to me. I sensed that she was being pressured by my father's continuing need to be accepted and assimilated, and by the social priorities of her own New York friends, whose daughters were no doubt being far more accommodating than I.

The Vietnam War was of far greater concern to me at that time than my social eligibility. Antiwar sentiment was in full cry at college campuses across the country, and Princeton was no exception. With the body count of U. S. and Vietnamese casualties mounting daily and a campus filled with draft-age young men, a debutante party seemed not only frivolous and embarrassing, but totally inappropriate. I could not fathom my parents' insensitivity. One day, while my mother sobbed her pleas to me over the phone, I finally relented but declared I would attend only one group event. I understood that my "coming out" party was not about me but about them.

A month after I started at Princeton, 250,000 people, the largest gathering yet, marched on Washington to protest the war. In solidarity, the entire campus observed Vietnam Moratorium Day and fasted while the headline of The Princetonian bannered: "Stop the War." The disclosure of America's secret intervention in Cambodia in the spring of 1970 triggered intense campus protests all over the country, including Kent State University, where protesting students were fired on by the Ohio National Guard. Four were killed and nine injured. The TV and newspaper images remain seared in my memory, especially the photograph of a young woman, Mary Ann Vecchio, kneeling by the dead body of a student, her arms outstretched in shock and her face contorted by the screams anyone looking at the photograph could hear.

The outrage was immediate. Violent protests against the Kent State killings erupted across America. The entire Princeton campus went on strike, and exams were canceled. During a protest at the Institute of Defense Analyses we were teargassed by anti-riot police.

It was a seminal moment in shaping my view of American society. While I loved my country, I found my trust in its institutions badly shaken. The war in Vietnam and the rapidity of the social and political changes sweeping the country had simply engulfed us. Many students were dropping out of school or taking leaves of absence at the time to examine and re-sort their priorities. I certainly did not feel I was getting as much out of university as I wanted to, and I did not want to waste the time I was there, so after three distracted semesters I decided to take a year's leave of absence to clear my head. In the winter of 1971 I went to Colorado, thinking I could easily find a job to support myself in a winter resort town. I arrived during a major winter storm and woke up on the floor of a trailer where I had been offered refuge during the blizzard.

My father was furious. He flew to Aspen, where I had found a job cleaning hotel rooms, to accuse me of "running away." But the opposite was true. I needed time and space to set my own priorities and to discover if I could survive on my own. However disappointed my father might have been, a sentiment he expressed in no uncertain terms, I knew the sabbatical was the right thing for me.

I worked as a maid, as a waitress in a pizza parlor, and as a part-time gofer at the Aspen Institute, making enough money to eat and pay my share of the rent in a house I was sharing with other young women. I attended my first Institute conference on "Technological Change and Social Responsibility," which featured the wisdom and expertise of the amazing inventor-architectgenius Buckminster Fuller. And I worked on an innovative architectural project, for an environmental school. Once again, I felt I was intellectually engaged.

I went back to Princeton after a year in Colorado and elected to major in architecture and urban planning. My course of study was an eclectic one, combining history, anthropology, sociology, psychology, religion, arts, physics, and engineering. I loved it. It was a captivating, multidisciplinary approach to understanding and addressing the most basic needs of individuals and communities. Architecture studies also provided me with some very practical skills—a reduced need for sleep, and practice in thinking on my feet when faced with merciless critiques of my work. Both of these would prove very useful in later life.

My father's job at Pan Am was about to end. He had lobbied the members of the Civil Aeronautics Board in Washington for a fair shake for the company, but Richard Nixon, a Republican, was President, and my father, a registered Democrat, could make no headway. Nixon's sta. was so partisan that my father was even included in John Dean's White House "enemies list," effectively killing any chance of federal support for Pan Am. (A few months later that paranoia would prove to be Nixon's undoing, as news of the Watergate scandal broke.) Mergers were a possible solution, but for various reasons none came to fruition. There were personnel problems, issues with the board of directors, differences with the top executives, and Pan Am's mounting debt. Finally it was over. On March 22, 1972, the board asked for—and received—my father's resignation.

My father observed later that Alexa, Chris, and I "seemed genuinely pleased" that he was no longer a "big business tycoon." "Whether that meant they wanted to see more of me or that they were embarrassed by trying to explain away Pan Am to their friends, I do not know," he said. I cannot speak for my sister or brother, but it was clear to me that he was far less suited to the cutthroat ways of the business world than he was to his first love—public and international service.

Soon after my father stepped down from Pan Am, the president of Jordan's national airline, Ali Ghandour, invited my parents to visit that country in the spring of 1973. Because my father seemed so tired, Ghandour arranged for my parents to spend a few days by the sea at the royal compound in Aqaba, and it was there that they met King Hussein. The two men hit it o. immediately. The King, then thirty-eight, told my father about his plans for expanding civil aviation in Jordan and asked him to act as an adviser. My father readily agreed. For the rest of their time in Jordan, my parents toured the ancient land's remarkable archaeological sites in the King's helicopter.

During my spring break from Princeton, I heard all about my parents' trip, especially their audience with King Hussein. My mother was enchanted by him and showed me a brooch he had given her, fashioned in the shape of a peacock and set with four small stones: sapphire, emerald, ruby, and diamond. He had chosen the different-colored stones, he had told her, because he did not know whether she would be a blonde, a brunette, or a redhead. So it was my mother who first brought King Hussein into my life, and in a very appealing way. "He has," she said, "the most beautiful, kind eyes."

Chapter Three

Tehran Journal

When I grauated from Princeton in 1974, I decided to take advantage of the Pan Am travel privileges extended to our family and to travel and work abroad in regions of special interest to me. I began in Australia, having been offered a job in the Sydney office of the British planning firm Llewelyn-Davis, but a significant revision of the country's immigration law coincided with my arrival and I was denied a work permit. In an amazing instance of serendipity, while considering my next steps, I happened to run into an old car-pool companion from my elementary school in California one day in Sydney. She was leaving her position at another architectural firm, which had projects in the Middle East. My Arab-American background uniquely qualified me to work on these projects from their Sydney office, making me eligible for the elusive Australian work visa.

After a year working in Australia, I attended an Aspen Institute symposium in Persepolis, near the ancient Persian capital of Shiraz, which was built some 2,500 years ago by King Darius the Great and finished by his son Xerxes. In Persepolis, the ruins came to life in a son et lumière show with a narrative about the accomplishments of the early Persian kings who extended the borders of the Persian Empire into Europe and India, built a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea and a network of roads that are still being used today, and even established a postal system. The sound and light show was a beautifully effective blend of music, poetry, and imagery that sent shivers down my spine. I could never have imagined at the time that I would be involved in later efforts to achieve a similar atmospheric and powerful dramatization of history in a sound and light presentation in the Jordanian city of Jerash. At that Aspen Institute conference I met for the first time Empress Farah Diba of Iran, who a few years later would become a dear and respected friend, though at the time our two worlds could not have appeared further apart. The Shahbanou hosted the final evening's banquet, held in grand tents erected five years earlier for the celebration honoring the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire, which had been the largest gathering of heads of state in history.

At the end of the conference, I was offered a fascinating opportunity to join Llewelyn-Davis in Iran. The firm had been hired by the Shah, Reza Pahlavi, to build a model city center on 1,600 acres in north Tehran. Shahestan Pahlavi ("town of the Shah Pahlavi") was an enormously ambitious undertaking and a personal interest of the Shah's. The project was an urban planner's fantasy.

The new city center, with its views of the snowcapped Alborz mountain range, was to feature pedestrian malls, theaters, moving sidewalks, shopping galleries, shaded arcades, and terraced gardens. Government ministry buildings and foreign embassies would rim one of the largest open public spaces in the world, to be called Shah and Nation Square. The scale was monumental: Shah and Nation Square was designed to be larger than Red Square in Moscow, and the Shahanshah Boulevard, the broad, tree-lined avenue through the project's center, was intended to emulate the Champs-Elysées in Paris. My work as a planning assistant entailed surveying and mapping all the buildings in the vast area surrounding the site.

When the Shah initiated the model city scheme, he was inspired by Shah Abbas the Great, a Persian leader and patron of the arts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Shah Abbas had transformed Esfahan, the former capital of Persia, into one of the world's great cities, with innovative architecture and a sweeping use of space. Located in the center of Iran, it is an island of green amid the vast desert plains, with magnificent buildings, like the Sheikh Lutfullah mosque and the Chehel Sotoon palace, and graced with wide boulevards, an abundance of bridges, and lush aromatic gardens. When I think of Esfahan, I see the intricately designed blue ceramic tiles that decorate so many of its buildings and the ubiquitous tearooms where Iranians would sit for hours, chatting and smoking water pipes.

I arrived in Tehran in the fall of 1975 There were about twenty of us working on the project, living in a cluster of apartments near the site. At twenty-four, I was the youngest of the group and the only woman. Many of my colleagues treated me like a little sister, making brotherly attempts to sophisticate me, encouraging me to use makeup and make more of an effort with my loose, flowing hair. Iranian women living in the city, like their Arab counterparts, tended to be elaborately formal in their appearance, jewelry, and dress. I possessed neither makeup nor jewels, only the bare necessities of an easily packed working wardrobe and jeans, having always assumed that character and professional merit would serve me better than my appearance.

Nonetheless I longingly admired the striking, filmy chadors of delicately printed chiffon and other fabrics that enveloped Iranian women of all ages and backgrounds as they moved about in public. I would happily have adopted that style of dress—so intensely feminine and mysteriously modest at the same time.

I loved walking in Tehran, wandering through the tangled maze of the bazaar and down Qajar Street, a pedestrian's delight of magnificent oriental carpets and wall hangings. Nearby, modern buses and automobiles vied for space with donkey carts. It was hard to describe Iran to my friends back in the United States because it defied easy categorization. Under those gossamer chadors, hip young women wore bellbottom jeans and platform shoes. When I traveled up to the vast Shahestan Pahlavi site, I passed by the palatial homes of Tehran's new rich, but in the south of the city I could barely breathe due to air pollution from refineries situated in the middle of neighborhoods where Iran's growing number of poor people lived. The treatment of women was nuanced as well. I never felt pressured or intimidated when traveling alone or moving from one place to another, but I was often stared at strangely, especially if I went to a restaurant alone for a meal.

Near the end of my stay, when most of our team had relocated to London, I would go out alone to eat quite often. Those were not easy moments—the embarrassed maitre d' did not quite know what to do when I showed up, and inevitably seated me o. in an obscure corner.

My journal from those days describes my feeling that the country seemed to have a split personality. On the one hand, it was very Western and cosmopolitan, with a large, well-educated middle class, and on the other, it retained an exotic, Middle Eastern flavor and a dynamic folk culture. It was in Iran that I sensed with even greater intensity what had struck me in visits to Mexico and Central America in the early 1970s—the vitality of a country expressed through its handicrafts. Persian carpets are the best-known example, but it was the intricate, finely detailed paintings on lacquered wood, delicate silver boxes with fine enameling, and drawings of historic scenes that captured my imagination. I learned that the Shah's wife, Empress Farah, had supported the handicrafts industry as a way of raising the living standards of the poor. Years later I would recall the Shahbanou's success when I initiated a project to revive and develop this aspect of Jordan's heritage.

It was in the homes of Iranians that I first became aware of the seeds of discontent that would develop into full-blown revolution just three years later. I was more fortunate than many foreigners in Tehran because I had family friends in the city, all of whom were very kind and hospitable. At dinners with Cyrus Ghani, a prominent lawyer and author of several books on Iran, and members of the extensive Farmanfarmaian family, I met artists, actors, and leading intellectuals, as well as government officials, and was exposed to differing perspectives on culture, politics, and social issues.

Many of the young professionals I met supported the direction in which the country was moving. One of the goals of the "White Revolution" the Shah had advanced in 1963 was ambitious land reform that would redistribute the vast holdings of the rich few to the many rural poor. The Shah had also championed women's rights. While I was living in Iran, he had placed Empress Farah in a position of enhanced authority. She put her support behind monthly gatherings of the country's best minds. In time, this group would be referred to as the Empress's think tank. In addition, his sister, Princess Ashraf, was serving as Iran's ambassador to the United Nations. I observed these developments with interest. As a young professional, I was intrigued by the special challenges facing women in their public and private lives, particularly highly visible and active women like the Shahbanou, who so often seemed to draw fire because of opposition to their husbands and for the failings of their society.

Despite these progressive goals, my friends were concerned that Iran was quickly becoming a heavy-handed police state. SAVAK, the Shah's secret police, was beginning to clamp down on any perceived threat to the regime, and I would meet people who were hesitant to say anything that might in any way be construed as critical. One popular employee at Llewelyn-Davis, a young Iranian architect, was summarily picked up o. the street by SAVAK and taken o. for interrogation. We were not sure whether we would see him again, but he returned the next day, badly shaken. Another morning, during a company meeting, project director Jaquelin Robertson passed a note over his desk for us to read; it indicated that our offices were bugged and that we should be on guard at every moment.

The warning was indicative of a growing restiveness. Conversations began to focus on the government and the image of the Shah and his family. In addition to the prominent and controversial Princess Ashraf, the Shah's wife was a convenient target. One story described her visit to a poor section of Tehran. Evidently, just prior to her arrival the city's mayor had the street paved over and arranged a complete face-lift for that part of town. This sparked a great deal of criticism, although most guests at the table, when pressed, acknowledged that the Empress probably was completely unaware that the mayor had whitewashed the situation to make it appear less desperate than it really was.

I learned about public reaction to the 1974 Shiraz Festival. The aim of the Shiraz Festival was perfectly commendable—to spark cross-pollination between Iran and the rest of the world through a program that reflected the latest trends in theater and the performing arts. Unfortunately, this approach backfired badly. A French theater company staged the musical Hair, which had shocked Western audiences at the time because of its nudity. Needless to say, it had a far more jarring effect in an Islamic culture.

There were other more substantive causes for the growing feeling of unrest. For one thing, the oil money that had started pouring into Iran in 1973 after the third Arab-Israeli war and the Arab oil embargo ended was upsetting the social structure and threatening the country's cultural equilibrium.

One could not miss the jolting juxtaposition of conservative and progressive. This incongruous mix was acceptable for the adaptable young middle class, but it was taking place in a society that also had strong conservative and religious underpinnings.

Huge economic gaps were growing between different segments of the society. In the rural areas outside Tehran, people lived very simply yet perhaps better than those in Tehran's growing slum areas, which often had unpaved roads, lacked electricity or sanitation, and offered the unskilled poor no way of bettering their lot. The Shah had instituted an ambitious program to eradicate illiteracy, but many of the poor had no education save what they learned at the madrasahs, or religious schools. Just as the government and the Shah were trying to close those gaps, they grew wider: The new oil wealth appeared to be increasingly and conspicuously concentrated in a small segment of the population.

After coming to know the city and its people, I became quite disturbed by the destructive environmental and social impact I imagined the mammoth Shahestan Pahlavi project would have on the only remaining green "lung" in the city's rapidly growing urban sprawl. Surrounded on three sides by mountains, Tehran was a virtual trap for pollution from refineries, car exhaust, and factories. The jubes—open canals lining the edges of the streets throughout the city—carried rainwater mixed with garbage and sewage across the city north to south. Traffic gridlocked certain sections of the city for hours. It was alarming to watch the deterioration of Tehran at the hands of rapid industrialization, especially since what had drawn me to the country was its extraordinary beauty.

Living in Tehran, I also became aware of the depth of religious fervor among the Shi'a branch of Islam, which is centered in Iran. I learned that the major difference between the Shi'a and Sunni branches of Islam is the issue of the right of succession from the Prophet Muhammad. When the Prophet died in A.D. 632, a majority of his followers believed that the Prophet's father-in-law, Abu Bakr, should be their spiritual leader. Another group believed that his rightful successor was his cousin and son-in-law, Ali. The latter group eventually formed the Shi'at Ali, the Party of Ali, and persisted in their belief that only Ali, his male heirs, or the members of the Prophet's household could be the rightful spiritual leader, or caliph, of Islam. However, the Sunni Muslims, who greatly outnumbered them, chose the caliph on merit by consensus. Despite the gulf between these two branches of Islam, they both viewed the Hashimites as spiritual leaders.

The rift between Shi'ites and Sunnis escalated into violence in A.D.680 After Imam Ali died, his son, Imam Hussein, received word in Mecca that the self-proclaimed new Umayyad caliph in Damascus was corrupt and a drunkard, and was not fit to be the spiritual leader of the Muslim world. Despite warnings from his advisers, Imam Hussein left the Hejaz (a region on the western coast of the Arabian Peninsula) with his family and a small army to challenge the spiritually corrupt caliph. In the bloody confrontation that followed, Imam Hussein was ambushed and murdered with seventy of his followers and family at Karbala in southern Iraq. By giving his life for Islam, Hussein became a shaheed, or martyr, central to the Shi'ite identity as oppressed and persecuted, and Karbala, where he is buried, became a holy place of pilgrimage. Since then the story of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein has played a key role in Shi'a religious thought and ritual, which also includes the staging of Shi'a Muslim "passion plays" that recount that tragic day in Imam Hussein's life to large crowds on the day of Ashura.

I was in Tehran during Ashura in 1976, and I shall never forget it. Early one morning, alone in my apartment, I heard a strange sound, loud, swelling and completely unrecognizable. It grew louder and louder, building to a roar. Looking out the window, I saw a procession of perhaps fifty men walking through the streets, flailing their bloodied bodies with chains. The sight was terrible and transfixing. At the time I had no idea what I was seeing and hearing. I learned later from Iranian friends that the self-flagellation is an expression of grief and shared suffering with Imam Hussein, whose infant son had been murdered in his arms, and whose head had been cut o. and paraded about on the point of a spear.