Excerpt

Excerpt

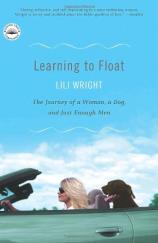

Learning to Float: The Journey of a Woman, a Dog, and Just Enough Men

Mermaid

I've never seen a mermaid, but for years I felt like one.

Half pretty woman. Half cold fish.

No one knows the precise origin of the folklore, but sailors from Scandinavia to the Caribbean have sighted these bare-breasted sirens perched on ocean reefs. The most common explanation is that sailors, overcome by sun and testosterone, mistook a manatee for a beautiful woman. Manatees and women do share certain traits. Both have hair. Both sun themselves. Both breast-feed their young. And, well, that's about it.

But apparently the isolation of a long sea voyage can take its toll on a man; he learns to let his vision blur with pent-up desire. One Arctic explorer understood this well and hired the ugliest hag he could find to serve as ship cook. When the old crone began to look good to him, he knew it was time to head home.

Though the myth of the mermaid dates back to ancient Greece, she's lost none of her allure. Wherever I drove that summer, from Kennebunkport to Key Largo, mermaids perked up T-shirts and billboards and roadside menus, inevitably copping the same cartoonish pose--huge breasts, a tantalizing golden mane, a curvaceous tail that slimmed to a wedged bottom fin. Mermaid as sex symbol; it has always struck me as odd. I mean, below the belly button, the woman has nothing but scales.

Then again, perhaps it's the logistical impossibility of possessing a mermaid that makes her so desirable. She's the lover who can't be kept, the lady fish who swims away. In revenge, the scorned suitor depicts her as caricature--a big-titted monster, a high-maintenance vamp with a hand mirror and comb. Maker of storms. Tormenter of ships. Seducer of seamen. Vargas Girl meets Flipper.

Yet, for some reason, I'd always seen mermaids as kindred spirits, independent women who artfully slip between worlds. A mermaid can woo a brawny seaman and, when she tires of him, flip her tail and dive down to play with silver fishes. But the more I thought this through, and I did a lot that summer, the more I decided I had it all wrong. A mermaid is the saddest sort of hodgepodge, fulfilled in neither world. Eye on land, tail in the sea, she lingers on the cold rocks, hoping to catch the eye of a passing sailor she'll never call her own.

At the Bar

Fenwick island, de. It was Happy Hour and the rummy crowd at Smitty McGee's had knocked back enough half-price drinks to feel sun-flushed and loose. Around large wood tables, beaming vacationers gorged on buckets of steamers. I sat alone at the U-shaped bar, breathing in cigarettes and radon, listening to the blender grind ice cubes into slush. Finally, Christi, with a name tag, arrived with my white wine, which was served in a fish bowl and tasted like apple juice distilled through dirty nickels.

"It's huge," I said.

"Twelve ounces," said Christi, smiling. Christi had a tan.

Twelve ounces was fine with me--I was looking to catch a buzz. A month ago, I'd fled New York and the romantic mess I'd made there. I do my best thinking near the ocean, like dull rocks that look brighter when wet, so I'd mapped out a coastal pilgrimage from Maine to Key West. I was thirty-three and single, a woman on the emotional lam. I couldn't go home until I made some decisions, until I knew what to say to whom. But so far, I hadn't come up with any great answers.

Christi returned with a menu. I wanted oysters, but funds were running low, so opted for a salad. Then I pulled out the Buddha book my friend Maurice had recommended, a three-inch tome I had been too impatient to read for more than a few minutes at a stretch. So far, Buddha was wandering around hoping to find a prophet who could show him the Way. It wasn't much of a plan and, in that way, reminded me of my own venture. As I was discovering, wanting to find the Way and finding the Way were two very different things. Siddhartha had been muddling along for a hundred pages or so, meditating, waiting for truth to reveal itself. He was more patient than Job. Meanwhile, I had meandered a thousand miles from Maine to Delaware, waiting for anything to reveal itself. Frankly, I was getting impatient--for him and for me.

I read a couple sentences. Buddha was focusing on eternal enlightenment; I started worrying about Stan. Stan was a cop I'd met that morning who'd offered to let me sleep in his trailer, no strings attached, no Stan attached--he'd be out of town working for a couple of days. Though originally this freebie had seemed like a real traveling coup, now that it was nearly dark, the initial trustworthiness he had conveyed seemed like a distant and perhaps unreliable first impression. The idea of sleeping in a strange man's trailer, a man whose face I could no longer clearly picture, a man who said he was a cop but who knew? . . . well, it wasn't the most secure situation. I resolved to drink myself brave or sleepy, whichever came first.

Of course, if I'd really been brave, I never would have called Stuart. A woman of substance should be able to sustain herself, I lectured the side of my brain willing to listen. A woman of substance should be able to sustain herself without phoning up her ex. Look at Buddha. He left behind his wife and son for seven years and traveled alone, and even when the Way-less monk had company, he ate his meals without speaking, in "mindfulness," trying to appreciate every precious grain of rice.

Reaching for my wine, I took a hefty gulp and tried to decide just how much mindfulness I'd need to make this house white grow precious.

Two men walked in and slid onto the bar stools next to me. The younger one, forty or so, ordered beers and pushed a couple of bucks Christi's way. He had a mustache, straight brown bangs, and reminded me of Sonny Bono, back in the Cher days, only with thick glasses and wafflely sneakers. Beyond him slouched an older guy, bulldoggish with long gray sideburns, neck like a frog. Under his VFW cap, he wore the empty expression of a man thinking hard about his next cold draft.

I pretended to read until the younger guy, the one sitting next to me, interrupted.

"You mind if I smoke?"

I looked up. A scar broke over the bridge of his nose like shattered glass.

"No," I said. "Go ahead."

I returned to Buddha. Then they ate in silence, mindful of each bite.

"You visiting?" he asked.

In bars, as on airplanes, it's always risky to start up a conversation with the guy sitting next to you, particularly if you're a single woman. A single woman at a bar sticks out like the final bowling pin waiting to be taken down. Still, when traveling alone, I'd rather eat with dubious company at the bar than alone in the dining room, if only to avoid that moment when the hostess peers over your shoulder and asks, "Just one?" as if you've never had a friend in your life.

Besides, tonight, I had nowhere to go but back to Stan's trailer and I wasn't in any hurry to get there, so conversation seemed like a fine idea. I closed Buddha, mindfully, looked hard into this guy's glasses to convey I was not flirting but simply passing time, and set to work opening him up, seeing what lay inside.

"Visiting," I said. "I'm in grad school, traveling for the summer. What about you?"

"Oh, I live here," he said, pushing back his sleeves. "Work as a dental technician."

"What kind?" I asked.

After being a reporter for ten years before grad school, I could usually gather someone's life story without revealing so much as my name. It isn't hard, really. Most people are desperate to find someone who will listen. Sure enough, this guy began yammering away about his work in dental care. He smoked a Camel, snuffed it out, and lit another. My salad arrived, and I dug into iceberg, while he smoked some more, eventually wrapping up his tale.

"My name's Carl," he said, holding out his hand. His nails were bitten to the quick.

"Lili," I said.

"Lily?"

"No, Lee-lee. Who's your friend?"

Carl looked confused. I pointed.

"Oh, that's my dad, Ward."

Ward looked over. I smiled and held out a neighborly hand. I felt bad the old guy had been sitting by himself all this time. His hand was shoe leathery, and he had great gray bags under his eyes.

"Nice to meet you Ward," I said, trying to be polite. "How are you?"

"Fine," he said slowly. "Been drinking since nine a.m."

He turned back to the TV.

Carl grinned, as if this admission were endearing.

"Is he serious?" I asked.

"He's retired," said Carl. "He's free to do what he wants. He's earned it."

I sipped my wine, digesting. Did that mean Carl had been drinking since breakfast? He didn't seem drunk, though I was quickly moving that direction. The bar had become warm and pleasantly fuzzy, like a sweatshirt turned inside out.

"You married?" asked Carl.

"No," I said. "You?"

I was going to hold up my end of the conversation. Tit for tat.

"Separated," said Carl, cleaning what was left of his nails with a matchbook. "Getting divorced."

"I'm sorry," I said. And I was. Just one more story of love gone south. We sat quietly for a moment or two. Carl ordered more beers. The bar was filling up. A chubby woman in a red tank top dangled her arm over her froggy guy, then wiggled her hand between two buttons and rubbed his chest.

"So what went wrong?" I asked.

"With what?"

"Your marriage."

Carl stirred his dead cigarette in the ashtray, making designs in the cinders.

"We were married nineteen years. Three kids. We had a house, a big house on the bay, a boat, forty-five horsepower. In the summer, we'd take the boat out on the bay, cruise around. The kids loved it."

He stopped. I waited a beat or two.

"Sounds nice," I said.

"It was nice," he said. "It was nice until it wasn't nice any more."

Carl took a defiant swig of beer, wedged his chin against the air. Foam clung to his mustache, tiny bubbles waiting to pop.

"Is your dad still married?" I said, trying to shift the subject, scrounge up a little hope.

"My mom passed away last year, but they stayed married for forty-two years."

"That's pretty great," I said, perking up. "So what was his secret?"

"I don't know." Carl waved his cigarette. "Why don't you ask him? Hey, Pop, I told this lady you and mom were married forty-two years, and she wants to know how you did it."

The old man craned his big head my way.

"It waren't easy." He turned back to the TV.

I smiled like this was a fine joke, then pushed back my salad. A cocktail tomato rolled around the bowl like a head without a body. Carl lit a cigarette, motioned Christi for another round. She brought two drafts and a wine.

"Oh, wow," I said. "You didn't have to do that."

Carl nodded.

I couldn't imagine drinking a second glass, mindfully or mindlessly, but I bravely set forth in that direction. Happy Hour was over and the lights had dimmed down to sexy and the tape deck was thumping like a heart in love. Young people pressed against the bar, all big teeth and cleavage.

Carl spoke up again, his voice thin and ghostly. "I guess it was a communication problem. There wasn't much point in talking any more. So we gave it up."

I could hear that silence. I saw his wife, a bony woman, pretty but frayed. She was still wearing her gray work skirt and stubborn pantyhose as she leaned on a vacuum cleaner in the second-floor hallway. Toys were scattered about, and you could tell by vacuum tracks molded into the carpet that she'd steered around the playthings instead of picking them up. On a wooden table under a mirror sat a mug of cold coffee, nondairy creamer congealed into a cumulus cloud. As she looked up, her mouth puckered like yesterday's rose. She took a sip, frowned, turned on the vacuum. The machine growled, sucking and wailing, filling its cavernous belly with whatever dirt it could find.

I sipped my wine, hoping old Carl was going to lighten up and tell me more about dentures, reassure me that love didn't have to come to this, but he tapped his fingers on the bar, lost in thought.

"It got so I couldn't stand the sight of her," Carl said slowly, as if I hadn't understood the first time, as if he wanted to make things perfectly clear. "She couldn't stand the sight of me. We couldn't stand the sight of each other."

I shuddered, watched his wife shut off the vacuum, turn her back, walk into the bedroom, close the sky-blue door. No love of mine had gotten that bad, but maybe I'd left before things ran their course.

It was time to go, but I wanted to get something from this man. A lesson perhaps, some nugget or quote to remember. In my experience, you're as likely to get decent advice from a stranger as a shrink, and you don't have to wait as long or pay as much or think up all the answers yourself. But you do have to be patient because the guy often drops the gem just when you're on the verge of giving up and hunting down someone who is, as TV journalists like to say, a "better talker."

Carl folded his cocktail napkin, then unfolded it and refolded it, like some origami project that wasn't going well. I ripped the cuticle on my thumb, a nervous habit I never realize I'm doing until I start to bleed.

"But I don't get it," I said, wondering if I sounded drunk and deciding no, not quite. "That's sort of why I'm taking this trip. Marriage terrifies me. I mean, forever is a long time, and how do you know when you've met the right person? What happened between you and your wife?"

Carl said nothing for several moments, just watched his smoke billow and plume. I sucked down wine like a thirsty plant. Who was I kidding? I was buzzed and feeling gloriously self-destructive, bold as the woman I wanted to be. Just when I assumed Carl had forgotten my question or didn't care to answer it, he looked at me hard, angry even, bullet eyes cocked, like I was the one who'd broken his heart, like this whole fiasco called love was my fault and he was ready to get even.

Learning to Float: The Journey of a Woman, a Dog, and Just Enough Men

- paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Broadway

- ISBN-10: 0767910044

- ISBN-13: 9780767910040