Excerpt

Excerpt

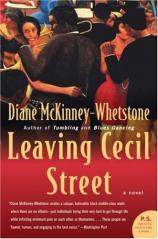

Leaving Cecil Street: A Novel

Chapter One

Cecil street was feeling some kind of way in 1969. Safely tucked away in the heart of West Philadelphia, this had always been a charmed block. A pleasure to walk through the way the trees lined the street from end to end and made arcs when they were in full leaf. The outsides of the houses stayed in good repair, with unchipped banister posts and porches mopped down daily because the people here sat out a lot, their soothing chatter jumping the banisters from end to end about how the numbers had come that day or what had happened on The Edge of Night. And even though the block had long ago made the transition from white to colored to Negro to Black Is Beautiful, the city still provided street cleaning twice a week in the summer when the children took to the outside and there was the familiar smack, smack of the double-Dutch rope. The sound was a predictable comfort. Like the sounds of the Corner Boys, a mildly delinquent lot consumed with pilfering Kool cigarettes or the feel of a virgin girl's behind. But as soon as Walter Cronkite signed off for the night, the Corner Boys put their voices together in a cappella harmonies that rushed this stretch of Cecil and felt like a new religion. They sang nice settling-down tunes about love and the blues. Sang as the bowls of chicken and dumplings or pans of corn bread or whatever somebody had cooked too much of were passed up and down the block. Sang while the teenagers gathered on steps under the street lamps to plait each other's hair so that their 'fros would grow out thick and full. Sang while the women who hadn't yet made the leap to the African bush put hot combs on the stove to touch up their edges for the next day. Stirred up a good nighttime mood on the block when they sang.

But now Cecil Street had a new mood working, a fire-in-the-belly feeling about bad to come. Horrible enough that Martin had been assassinated last year, but in March the wrong cracker pled guilty, they believed. The government is the cracker should be on trial, they maintained as they hosed down their fronts of the dripped Popsicle juice. Then the undeclared war was threatening to take down as many of the young black men as the heroin that some swore was being pushed in their neighborhood by the CIA. Then the milkman stopped delivering around here, and Sonny went up on his hoagies by twenty cents. Then Tim, who owned the barbershop on the corner and the apartment above it that he regularly loaned out for the pleasure takings of his married men friends, was almost stomped to death under the el stop when the police mistook him for someone who'd robbed the PSFS with a water gun. Then BB, who worked in the shadows of her back bedroom freeing the women who'd gotten caught when their diaphragms or rhythm methods failed, had her purse snatched on Sixtieth Street; she 'd just performed back-to-back procedures and was on her way to buy two hundred dollars' worth of money orders to send to her mother down south who was raising BB's severely retarded child. The market two blocks over started disrespecting the hardworking homeowners around here by keeping dirty floors and wilted lettuce and day-old bread. And now this: the tree in front of Joe and Louise's house died.

It was the summer of '69 and Joe missed that tree. Missed it so much that he put awnings out front to try and duplicate its shade. Generally upbeat, Joe felt sad about the tree right now as he stood on his porch at two in the morning, shocked again by the sight of the stump where the tree should be. Felt sad generally right now even though this was the night that his close-knit block of Cecil Street had opened itself up for the annual block party and Joe had even danced in the street earlier to "Boogaloo Down Broadway." He reasoned he was absorbing what the rest of the block seemed to be feeling lately, edgy and discontented, otherwise he had no explanation for why, now, he was out on his porch at two in the morning lifting up the square of the porch floor that led to his cellar. He hadn't been down in the cellar since the spring, but he pushed through the dust and mold and spiderwebs down there -- and the darkness. He 'd forgotten about the short in the light. His hand went instinctively to his shirt pocket for matches to give himself a spark to see by. Remembered now no shirt pocket because he was wearing a dashiki. Didn't usually wear dashikis but had worn one for the block party, worn it also hoping to impress the young woman Valadean, up here for the summer visiting relatives across the street. "Who you supposed to be, Super Black Jack?" his wife, Louise, had remarked when she'd seen him in the dashiki.

He stretched his arms through the black air in the cellar, trying to feel his way so that he wouldn't collide full body into what he could not see. Couldn't see, stacked along the wall, the boxes that should have gone to Goodwill the month the light went, couldn't see the milk crates filled with his teenage daughter's outgrown toys; couldn't even see the oil heater that took up a quarter of the wall. Nor could he see the puffy-haired, naked woman making herself go flat against the wall, between the toys and the heater.

Deucie Powell. She wasn't from this part of Philly. She had turned onto Cecil Street earlier looking for her grown daughter's house, wanted to reintroduce herself to her daughter after a gulf of seventeen years. Wanted to reclaim her. But she 'd gotten disoriented by the block party and ended up naked in this cellar ...

Leaving Cecil Street: A Novel

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060722894

- ISBN-13: 9780060722890