Excerpt

Excerpt

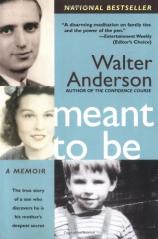

Meant to Be

Chapter One

I immediately recognized the blue suit. He had bought it years before from Mr. Freeman, a salesman who sold clothes and shoes door-to-door in our old neighborhood. This suit -- the only one he owned -- had seen some weddings and retirement dinners in its time, but mainly it had been worn to funerals. And now it had arrived at its last funeral: his.

The morticians had carefully dressed him in the old blue suit, a white shirt and a blue tie, then placed his body inside a polished wood casket, arranging his forearms so that his right hand crossed neatly over his left. It was on his face, though, where the craftsmen of the Burr Davis Funeral Home in Mount Vernon, New York, had proved their craft, accomplishing a remarkable feat: The late William Henry Anderson seemed serene -- his eyes closed, his expression neutral, as if he were enjoying a deep and peaceful sleep.

Where is the rage now? I wondered.

A few hours earlier, my brother Bill had given me a copy of the obituary that had appeared that day, February 7, 1966, in the local newspaper, the Daily Argus:

William H. (Whitey) Anderson Sr., 56, a retired troubleshooter for Con Edison, died yesterday at the U.S. Veterans Hospital in the Bronx. Mr. Anderson, son of the late Henry W. and Edith (Heikkela) Anderson, was born April 23, 1909, in New Rochelle. A Mount Vernon resident for 35 years, he was a volunteer fireman in Engine 2 and company captain for 14 years. He was a World War II veteran. Surviving are his wife, Ethel (Crolly) Anderson; two sons, William H. Anderson Jr. of Mount Vernon and Sgt. Walter H. Anderson, a U.S. Marine; a daughter, Mrs. Carol Gennimi of Yorktown Heights; a sister, Mrs. Dhyne Seacord of Elmhurst, L.I.; and five grandchildren.

I remembered his boast: "When I go, they'll all be there!" And they were. The funeral parlor was filled. Dozens of firemen who knew him from his days as a volunteer filled the rear rows. Former co-workers from Con Edison, relatives and family friends from Mount Vernon, Saratoga, New Jersey and Long Island had found seats or queued in the side aisles.

My sister, Carol, was seated in the front row next to my mother. My brother, who had been an Engine 2 volunteer himself but was now a paid firefighter, finished greeting his fellow firemen, then joined me standing in the rear.

"I don't see any of the Cheatham brothers," I told Bill. "Aren't they coming?"

From the age of five until I quit high school at sixteen to enlist in the Marines, we had lived in a tenement on the corner of Eleventh Avenue and Third Street -- directly across from Cheatham Brothers Moving and Storage Company.

"No," Bill said. "The Cheathams won't be coming. Out of respect. Mom told me they called her."

Strange, I thought, that my brother didn't say the words "colored" or "Negro" or "black." He knew that his father's best friends, his favorite drinking buddies, were absent because of their race, that they must have decided their presence would cause discomfort or be unwelcome.

I guess I was still mulling this contradiction after the eulogy began, because the minister was well into it before I realized that I didn't recognize the man whose virtues he was praising: "Loved and loving"? How about "feared"? "Kind"? How about "rough"? "Respect for the Scriptures"? Where did that come from?

"Who the hell is he talking about?" my brother whispered. "The old man would not go for this."

"Amen," I said.

Then my mother -- to the genuine surprise of my brother, my sister, me and probably everyone else in the room who knew her well -- began crying hysterically, pleading, "Willie, take me with you!" Before we left the parlor, my sister, brother and I did our best to soothe her, and we must have succeeded, because she was relaxed when we got her home.

Two days later, the pastor spoke only briefly at the Beechwoods Cemetery in New Rochelle. My sister, her husband and I then drove to my mother's one-bedroom apartment in Mount Vernon, where I was staying on emergency leave from the Marines.

"When are you going back to San Diego?" my sister asked me.

"I have to return to the base by Saturday," I told her. "Meanwhile, I'll stay with Mommy, so she won't be alone."

"Now that Daddy is gone, are you still planning to stay in California when you're discharged?"

I knew that really wasn't meant to be a question. Carol was persistent. Now that I had returned safely from Vietnam, my sister wanted her little brother to come home forever.

"California's my future," I said, and in an attempt to quickly close the discussion, I added, "I'm going to go to college there."

"They have colleges here, you know," Carol persisted.

"Thanks," I said. "I knew that."

She made a face. This was merely the second or third round of Carol's campaign, I was sure. I could count on more discussions over the next couple of days before I returned to San Diego.

About an hour later, after my sister and her husband had gone, my mother and I sat alone in her living room. As we spoke, I could see her demeanor change dramatically. She was at ease now, talkative, even lively.

I encouraged her as she reminisced, and I listened closely as she again repeated in detail the circumstances surrounding her husband's death, which had been caused by a cerebral hemorrhage. She described the funeral, who had come, what they had said. She recalled for me the best times of her marriage, then the worst. It was as if she had an overpowering need to express herself. It was a bursting dam. Finally the flood subsided, and she sat quietly ...

Meant to Be

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: Harper Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0060099070

- ISBN-13: 9780060099077