Excerpt

Excerpt

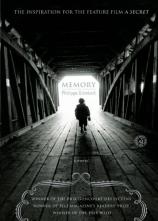

Memory

Although an only child, for many years I had a brother. Holiday friends and casual acquaintances had no option but to take my word for it. I had a brother. Stronger and better looking. An older brother, invisible and glorious.

I always felt envious when I went to stay with a friend and a similar-looking boy walked in. The same disheveled hair and lopsided grin would be introduced with two words: “My brother.” An enigma, this intruder with whom everything must be shared, even love. A real brother. Someone in whose face you discovered like features: a persistently straying lock of hair, a pointy tooth . . . A roommate of whom you knew the most intimate things: moods, tastes, weaknesses, smell. Exotic, for me who reigned alone over the empire of my family’s four-room flat.

I was the sole object of the love and tender care of my parents, yet I didn’t sleep well, troubled by bad dreams. I would start crying as soon as my light was turned out, not knowing for whom I wept the tears that sank into my pillow and disappeared into the night. Ashamed without understanding why, and often riddled with senseless guilt, I would delay my drift into sleep. As a child, every day provided me with sorrows and fears that I fueled with my solitude. I needed someone with whom to share those tears.

A day came when I was no longer alone. I had insisted on accompanying my mother to the attic, which she wanted to tidy. I discovered a musty-smelling, unknown room under the rafters, full of rickety furniture and piles of suitcases with rusty locks. She opened a trunk in which she expected to find the fashion magazines that used to publish her designs. She jumped when she saw the little dog with Bakelite eyes, sleeping there on top of a pile of blankets. Threadbare and dusty-muzzled, he was wearing a knitted coat. I immediately grabbed him and hugged him to my chest, but had to abandon the idea of taking him to my room: I could feel my mother’s unease as she asked me to put him back in his place.

That night, for the first time, I rubbed my wet cheek against a brother’s chest. He had just come into my life; I would take him with me everywhere.

From that day on I walked in his tracks, drowning in his shadow as in an oversize suit. He came with me to the park, to school; I talked about him to everyone I met. At home, I even made up a game to bring him into our lives: I insisted that we wait for him before sitting down at table, that he be served before me, that his bags be packed before mine when we went on holiday. I had created a brother behind whom I could withdraw, a brother who would burden me with the full force of his weight.

Although I hated my thinness and sickly pallor, I wanted to believe that I was my father’s pride and joy. My mother adored me --- I was the only one to have lived inside that toned belly, to have appeared from between those athletic thighs. I was the first, the only one. Before me, nobody. Just a night, some shadowy memories, and a few black-and-white photographs celebrating the meeting of two superb bodies, fit from athletic discipline, who would unite their paths to give me life, love me, and lie to me.

According to them, I had always had this very French surname. My origins didn’t condemn me to certain death; I was no longer a spindly branch at the top of a family tree in need of pollarding.

My christening took place so late that I could still remember it all: the gestures of the officiating priest, the damp cross imprinted on my forehead, and leaving the church held close under the embroidered wing of his stole. A bastion between me and divine wrath. If by misfortune its thunder should rage once more, my name on the sacristy register would protect me. I didn’t know what was going on and joined in the game obediently, silently, trying to believe --- along with everyone present --- that we were merely making up for a simple oversight.

The indelible cut to my penis became nothing more than the reminder of a necessary surgical intervention. Not a ritual but a medical decision, one among many. Our surname too was scarred: my father had arranged for two letters to be changed by deed poll, creating a different spelling that allowed him to plant roots deep in French soil.

The destructive mission undertaken by killers a few years before my birth thus continued underground, spreading secrets and silences, cultivating shame, mutilating names, and engendering lies. In defeat, the persecutor continued to triumph.

Despite these precautions the truth bubbled to the surface, thanks to certain details: a few slices of unleavened bread dipped in egg and fried until golden; a modern-style samovar on the living room mantelpiece; a candlestick locked into the cupboard beneath the dresser. And the constant questions: people were always asking me about the origins of the name Grimbert, wondering how exactly it was spelled, unearthing the n that an m had replaced, flushing out the g that a t was supposed to efface from memory. I brought these questions home; they were brushed aside by my father.We’ve always had that name, he would snap. That much was obvious and not to be contradicted: our name could be traced right back to the Middle Ages --- wasn’t Grimbert a hero of the Roman de Renart? An m for an n, a t for a g; two tiny changes. But of course M for mute hid the N of Nazism, while G for ghosts vanished under taciturn T.

I was constantly bashing up against the painful wall with which my parents had surrounded themselves, but loved them too much to try to climb it, reopening the wound. I had decided not to know.

For a long time my brother helped me surmount my fears. A squeeze of his hand on my arm, his fingers ruffling my hair, and I would find the strength to overcome obstacles. Sitting at a school desk, his shoulder against mine provided reassurance, and often when I was asked a question, his voice whispered the correct answer into my ear.

He displayed the pride of rebels doing exactly as they pleased, playground champions jumping for balls, heroes climbing the railings. I admired them, my back against the wall, incapable of competing, praying for the liberating bell so I could finally get back to my books. I had chosen myself a triumphant brother. Unbeatable, he won everything while I paraded my fragility before my father, trying not to see the disappointment flickering in his eyes.

My parents, my dear parents, whose every muscle had been buffed and toned, like those statues in the galleries of the Louvre that I found so unsettling. High-board diving and gymnastics for my mother, wrestling and apparatus work for my father, tennis and volleyball for the two of them; their bodies made to meet, marry, and reproduce.

I was the fruit of this union, but would stand in front of the mirror with morbid pleasure, enumerating my imperfections: bony knees, pelvis showing through the skin, gangly arms. How frightening I found that hollow beneath my solar plexus, about the size of a fist, gouging out my chest like the permanent mark of a blow.

Doctors’ surgeries, dispensaries, hospitals. The smell of disinfectant barely covering the sour sweat of fear. A noxious environment to which I added my own contribution, coughing under the stethoscope, stretching out my arm for the needle. Every week my mother took me to one of these now familiar places, helping me undress to display my symptoms to a specialist who would then take her away for a private, whispered conversation. Resigned, I remained on the examination table awaiting a verdict: some kind of intervention no doubt, or long-term treatment --- at the very best vitamins or inhalations. Years spent treating this faltering body. Meanwhile my brother brazenly showed off his broad shoulders and suntanned skin covered in downy blond hair.

Chinning bar, weights bench, wall bars . . . my father trained every day in a room of our flat, which they’d converted into a gym. Although my mother spent less time in there, she did use it for warm-up exercises, watching for the slightest slackening so she could remedy it immediately.

The two of them ran a wholesale business on the rue du Bourg-l’Abbé, in an area specializing in hosiery, in one of the oldest neighborhoods of Paris. Most of the sports shops bought their swimsuits, leotards, and underwear from my parents. I would stand at the till with my mother, greeting the clients. Sometimes I would help my father, trotting behind him into one or other of the storerooms to watch him effortlessly pick up stacks of boxes adorned with photos of sportsmen and -women --- gymnasts on the rings, swimmers, javelin throwers --- which he would then pile onto the shelves. The men had the same short, slightly wavy hair as my father; the women shared my mother’s dark cascade, tied back with a ribbon.

Soon after my discovery in the attic I had insisted on going back up there, and this time my mother couldn’t stop me bringing the little dog down with me. I moved him on to my bed that very evening.

Whenever I fell out with my brother I took refuge in my new friend, Si. Where did I get that name? From the dusty smell of his fur? The silences of my mother, my father’s sadness? Si, Si! I walked my dog all around the flat, not wanting to notice my parents’ distress when they heard me calling his name.

The older I got, the more tense my relationship with my brother became. I invented quarrels and rebelled against his authority. I tried to make him yield, but I rarely came out the winner.

He had changed over the years. From protective, he had become tyrannical, mocking, even contemptuous. I nevertheless continued to tell him my fears and failings as I fell asleep to the rhythm of his breathing. He received them without a word, but his gaze reduced me to nothing; he would examine my imperfections, lifting the sheets and stifling a laugh.Then anger would overwhelm me, and I’d seize him by the throat. Enemy brother, false brother, ghost brother, return to your night! Fingers in his eyes, I would push down on his face as hard as I could, trying to force him into the shifting sands of the pillow.

He laughed, and the two of us rolled around under the covers, reinventing crazy games in the half-light of our bedroom. Unsettled by his touch, I imagined the softness of his skin.

My bones lengthened, drawing attention to my skinniness. The school doctor noticed and summoned my parents to check that I was getting enough to eat. They came back distressed.Though I was angry with myself for making them feel ashamed, in my eyes their glamour was only reinforced: I hated my body, and my admiration for theirs now knew no bounds. I was discovering a new way to take pleasure in my loser status: lack of sleep hollowed out my cheeks a little more each day, the startling good health of my parents contrasting ever more with my sickly appearance.

My face had the pallor and bluish rings under the eyes of a child exhausted by solo activities.Whenever I shut myself in my room I took with me the image of a body, the warmth of flesh.When I wasn’t entangling my limbs with those of my brother, I cherished the thunderbolt that jolted through me every break time; in the playground I used to take refuge on the edge of the girls’ area --- they played hopscotch and skipping rope there, far from the ball games and shouts that rang out on the boys’ territory. Sitting on the cement floor close to their high voices, I let myself be soothed by their laughs and rhymes, and when they jumped, caught a glimpse of white knickers under skirts.

My curiosity about bodies was limitless. Very soon the shield of clothing ceased to hide anything from me; my eyes were like those magic glasses I had seen advertised in a magazine, claiming to be as strong as X rays. Released from their town clothes, passersby revealed both their treasures and their failings. I barely had to glance to notice a crooked leg, a perky pair of breasts, or a protuberant belly. My trained eye gathered a veritable harvest of images, a collection of bodies that I pored over when night came.

In the rue du Bourg-l’Abbé, I made the most of days when my parents were busy to explore the stock. The shop was on the ground floor of a dilapidated building. A staircase led up to what had been a flat; the dark rooms were lined with shelving and suffused with the smell of cardboard and paint. Just as I might have scoured library shelves for a particular book, I let my gaze run along the labels: swimming costumes, sports knickers, footless tights. Small, medium, large, girl, woman; I compared them all, taking note of the sizes, each number making me imagine a new body suddenly clothed in these items. When I was sure I wouldn’t be disturbed I opened the boxes, heart beating wildly, and grabbed the contents. I sank my face into them, and then laid them out on the counter while pressing my stomach up against the oak trim, trying in my own way to re-create the pose of a gymnast, basketball player, or longdistance runner.

The shop shared the ground floor of the building with the consulting rooms of Mademoiselle Louise. Her domain consisted of two rooms: an office and a treatment room, both painted glossy white with linoleum floors. A few sickly plants dressed a window on which enamel letters described the services available: home treatments, injections, massages. Louise was family; I had always known her. On quiet days she would come and lean on the counter to have a chat. She regularly massaged my parents on a table covered with a white sheet, and once a week injected me with vitamins or sat me down in front of her aerosol pump: I would sit quite still as the nozzles spluttered up into my nostrils, plunged in thought, made drowsy by the humming of the machine.

Louise was in her sixties. Her face bore the scars of alcohol and tobacco; years of excess had given her permanent bags under the eyes, and her pale skin floated loosely on a ruined face. Only her vigorous hands, emerging from the sleeves of her white coat, seemed to have bone structure: two authoritative hands, with short nails and long fingers that fluttered and asserted themselves as she spoke. I enjoyed her company, and would cross the narrow, box-filled corridor as often as possible to visit her. I spent less time at the shop than at her place, where I could talk freely. I felt close to her, probably because of her lopsided walk --- the result of a clubfoot hidden in an orthopedic shoe: a black leather ball and chain that she dragged with her everywhere. Her unsteady body bumping into the corridor walls seemed an echo of her face, a sack of skin unsupported by any framework. Prone to rheumatic episodes that inflamed her joints, Louise waved the dull pain away with an exasperated flick of her hand. I understood why: she hated the way she looked.

I was fascinated by her boneless body, so intimate with our own: those of my parents, who regularly dumped their tiredness on her massage table, and mine too, when I turned my naked buttocks to her so she could inject one of her regenerative potions.

Louise said she’d known my parents since they moved to the rue du Bourg-l’Abbé. She would rave about my mother’s beauty and my father’s stylishness, quivering as she said their surname.

We had our rituals. Whenever I dropped by she made me a hot chocolate on the little stove she used for boiling her needles. I sipped it slowly, and she kept me company with a glass of the amber liqueur she hid in her medicine cabinet. I was curious about her life, and asked her the questions I’d never allowed myself to ask my parents. She claimed she had no secrets --- this was her life, in these gloomy rooms, treating her regulars, listening to them day after day. The rest was so uninteresting: she lived in the house she’d been born and grown up in --- her horizons extended no farther than the two consulting rooms and the limestone house with its small suburban garden. Since her father’s death she had cared for her mother there, spending her evenings treating the frail old woman in much the same way she looked after clients during the daytime.

On days more favorable to the telling of secrets, Louise talked of having been mocked for her limp as a young girl, and living in the shadow of her more agile friends. I could relate to that. I wanted to know more, but almost immediately --- as with every time she spoke about something difficult --- Louise did that same thing to get rid of the pain: she swept the air with her hands and looked questioningly into my eyes,waiting for me to confide in her.Which gave me license to tell her my dreams.These tales of mine were punctuated by my sighs, made visible by the smoke of her cigarette.

For years she had been listening to my parents with the same attention, letting her strong hands run over them and rid them of their worries: along with their tiredness, they deposited their secrets with her.

Memory

- paperback: 176 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1416560009

- ISBN-13: 9781416560005