Excerpt

Excerpt

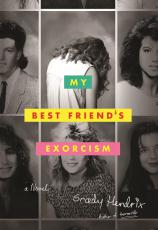

My Best Friend's Exorcism

DON’T YOU FORGET ABOUT ME

The exorcist is dead. Abby sits in her office and stares at the email, then clicks the blue link. It takes her to the homepage of the paper she still thinks of as the News and Courier, even though it changed its name fif- teen years ago. There’s the exorcist floating in the middle of her screen, balding and with a ponytail, smiling at the camera in a blurry headshot the size of a postage stamp. Abby’s jaw aches and her throat gets tight. She doesn’t realize she’s stopped breathing.

The exorcist was driving some lumber up to Lakewood and stopped on I-95 to help a tourist change his tire. He was tightening the lug nuts when a Dodge Caravan swerved onto the shoulder and hit him full-on. He died before the ambulance arrived. The woman driving the minivan had three different painkillers in her system— four if you included Bud Light. She was charged with driving un- der the influence.

“Highways or dieways,” Abby thinks. “The choice is yours.”

It pops into her head, a catchphrase she doesn’t even remember she remembered, but in that instant she doesn’t know how she ever forgot. Those highway safety billboards covered South Carolina when she was in high school; and in that instant, her office, the conference call she has at eleven, her apartment, her mortgage, her divorce, her daughter—none of it matters.

It’s twenty years ago and she’s bombing over the old bridge in a crapped-out Volkswagen Rabbit, windows down, radio blasting UB40, the air sweet and salty in her face. She turns her head to the right and sees Gretchen riding shotgun, the wind tossing her blond hair, shoes off, sitting Indian-style on the seat, and they’re singing along to the radio at the top of their tuneless lungs. It’s April 1988 and the world belongs to them.

For Abby, “friend” is a word whose sharp corners have been worn smooth by overuse. “I’m friends with the guys in IT,” she might say, or “I’m meeting some friends after work.”

But she remembers when the word “friend” could draw blood. She and Gretchen spent hours ranking their friendships, trying to determine who was a best friend and who was an everyday friend, debating whether anyone could have two best friends at the same time, writing each other’s names over and over in purple ink, buzzed on the dopamine high of belonging to someone else, having a total stranger choose you, someone who wanted to know you, another person who cared that you were alive.

She and Gretchen were best friends, and then came that fall. And they fell.

And the exorcist saved her life.

Abby still remembers high school, but she remembers it as images, not events. She remembers effects, but she’s gotten fuzzy on the causes. Now it’s all coming back in an unstoppable flood. The sound of screaming on the Lawn. The owls. The stench in Margaret’s room. Good Dog Max. The terrible thing that hap- pened to Glee. But most of all, she remembers what happened to Gretchen and how everything got so fucked up back in 1988, the year her best friend was possessed by the devil.

WE GOT THE BEAT

1982. Ronald Reagan was launching the War on Drugs. Nancy Reagan was telling everyone to “Just Say No.” EPCOT Center was finally open, Midway released Ms. Pac-Man in arcades, and Abby Rivers was a certified grown-up because she’d finally cried at a movie. It was E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and she went back to see it again and again, fascinated by her own involuntary reaction, helpless in the grip of the tears that washed down her face as E.T. and Elliott reached for each other.

It was the year she turned ten. It was the year of The Party. It was the year everything changed. One week before Thanksgiving, Abby marched into Mrs.

Link’s fourth-grade classroom with twenty-one invitations shaped like roller skates and invited her entire class to Redwing Rollerway on Saturday December 4 at 3:30 p.m. to celebrate her tenth birth- day. This was going to be Abby’s moment. She’d seen Roller Boogie with Linda Blair, she’d seen Olivia Newton-John in Xanadu, she’d seen shirtless Patrick Swayze in Skatetown, U.S.A. After months of practice, she was as good as all three of them put together. No longer would she be Flabby Quivers. Before the eyes of everybody in her class she would become Abby Rivers, Skate Princess.

Thanksgiving break happened, and on the first day back at school Margaret Middleton walked to the front of the classroom and invited everyone to her polo plantation for a day of horseback riding on Saturday, December 4.

“Mrs. Link? Mrs. Link? Mrs. Link?” Abby waved her arm wildly from side to side. “That’s the day of my birthday party.”

“Oh, right,” Mrs. Link said, as if Abby had not thumbtacked an extra-large roller skate with her birthday party information right in the middle of the classroom bulletin board. “But you can move that.”

“But . . .” Abby had never said “no” to a teacher before, so she did the best she could. “But it’s my birthday?”

Mrs. Link sighed and made a reassuring gesture to Margaret Middleton.

“Your party isn’t until three thirty,” she told Abby. “I’m sure everyone can come to your party after riding horses at Margaret’s.” “Of course they can, Mrs. Link,” Margaret Middleton simpered. “There’ll be plenty of time.” On the Thursday before her birthday, Abby brought the classroom twenty-five E.T. cupcakes as a reminder. Everyone ate them, which she thought was a good sign. On Saturday, she forced her parents to drive to Redwing Rollerway an hour early so they could set up. By 3:15 the private party room looked like E.T. had explod- ed all over the walls. There were E.T. balloons, E.T. tablecloths, E.T. party hats, snack-sized Reese’s Pieces next to every E.T. paper plate, a peanut butter and chocolate ice cream cake with E.T.’s face on top, and on the wall behind her seat was Abby’s most treasured possession that could not under any circumstances get soiled, stained, ripped, or torn: an actual E.T. movie poster her dad had brought home from the theater and given to her as a birthday present.

Finally, 3:30 rolled around.

No one came. At 3:35 the room was still empty. By 3:40 Abby was almost in tears. Out on the floor they were playing “Open Arms”by Journey and all the big kids were skating past the Plexiglas window that looked into the private party room, and Abby knew they were laughing at her because she was alone on her birthday. She sunk her fingernails deep into the milky skin on the inside of her wrist, focusing on how bad it burned to keep herself from crying. Finally, at 3:50, when every inch of her wrist was covered in bright red half-moon marks, Gretchen Lang, the weird new kid who’d just transferred from Ashley Hall, was pushed into the room by her mom.

“Hello, hello,” Mrs. Lang chirped, bracelets jangling on her wrists. “I’m so sorry we’re— Where is everybody?”

Abby couldn’t answer.

“They’re stuck on the bridge,” Abby’s mom said, coming to the rescue.

Mrs. Lang’s face relaxed. “Gretchen, why don’t you give your little friend her present?” she said, cramming a wrapped brick into Gretchen’s arms and pushing her forward. Gretchen leaned back, digging in her heels. Mrs. Lang tried another tactic: “We don’t know this character, do we, Gretchen?” she asked, looking at E.T.

She had to be kidding, Abby thought. How could she not know the most popular person on the planet?

“I know who he is,” Gretchen protested. “He’s E.T. the . . . Extra-Terrible?”

Abby could not even fathom. What were these crazy lunatics talking about?

“The extraterrestrial,” Abby corrected, finding her voice. “It means he comes from another planet.”

“Isn’t that precious,” Mrs. Lang said. Then she made her ex- cuses and got the hell out of there.

A deadly silence poisoned the air. Everyone shuffled their feet. For Abby, this was worse than being alone. By now, it was completely clear that no one was coming to her birthday party, and both of her parents had to confront the fact that their daughter had no friends. Even worse, a strange kid who didn’t know about extraterrestrials was witnessing her humiliation. Gretchen crossed her arms over her chest, crackling the paper around her gift.

“That’s so nice of you to bring a present,” Abby’s mom said. “You didn’t have to do that.”

Of course she had to do that, Abby thought. It’s my birthday.

“Happy birthday,” Gretchen mumbled, thrusting her present at Abby.

Abby didn’t want the present. She wanted her friends. Why weren’t they here? But Gretchen just stood there like a dummy, gift extended. With all eyes on Abby, she took the present, but she took it fast so that no one got confused and thought she liked the way things were going. Instantly, she knew her present was a book. Was this girl totally clueless? Abby wanted E.T. stuff, not a book. Unless maybe it was an E.T. book?

Even that small hope died after she carefully unwrapped the paper to find a Children’s Bible. Abby turned it over, hoping that maybe it was part of a bigger present that had E.T. in it. Nothing on the back. She opened it. Nope. It really was a Children’s New Testament. Abby looked up to see if the entire world had gone crazy, but all she saw was Gretchen staring at her.

Abby knew what the rules were: she had to say thank you and act excited so nobody’s feelings got hurt. But what about her feelings? It was her birthday and no one was thinking about her at all. No one was stuck on the bridge. Everyone was at Margaret Middleton’s house riding horses and giving Margaret all of Abby’s presents.

“What do we say, Abby?” her mom prompted.

No. She would not say it. If she said it, then she was agreeing this was fine, that it was okay for a weird person she did not know to give her a Bible. If she said it, her parents would think that she and this freak were friends and they’d make sure she came to all of Abby’s birthday parties from now on and she’d never get another present except Children’s Bibles from anyone ever.

“Abby?” her mom said. No. “Abs,”her dad said. “Don’t be like this.” “You need to thank this little girl right now,”her mom said. In a flash of inspiration, Abby realized she had a way out: she could run. What were they going to do? Tackle her? So she ran, shoulder-checking Gretchen and fleeing into the noise and dark- ness of the rink.

“Abby!” her mom called, and then Journey drowned her out.

Super sincere Steve Perry sent his voice soaring over smash- ing cymbals and power-ballad guitars that pounded the rink walls with crashing waves as cooing couples skated close.

Abby wove between big kids carrying pizza and pitchers of beer, all of them rolling across the carpet, shouting to their friends, then she crashed into the ladies’ room, burst into a stall, slammed the orange door behind her, collapsed onto the toilet seat, and was miserable.

Everyone wanted to go to Margaret Middleton’s plantation because Margaret Middleton had horses, and Abby was a stupid moron if she thought people wanted to come see her skate. No one wanted to see her skate. They wanted to ride horses, and she was stupid and stupid and stupid to think otherwise.

“Open Arms” got louder as someone opened the door. “Abby?” a voice said. It was what’s-her-name. Abby was instantly suspicious. Her parents had probably sent her in to spy. Abby pulled her feet up onto the toilet seat.

Gretchen knocked on the stall door. “Abby? Are you in there?” Abby sat very, very still and managed to get her crying down to a mild whimper. “I didn’t want to give you a Children’s Bible,”Gretchen said, through the stall door. “My mom picked it out. I told her not to. I wanted to get you an E.T. thing. They had one where his heart lit up.”

Abby didn’t care. This girl was terrible. Abby heard movement outside the stall, and then Gretchen was sticking her face under the door. Abby was horrified. What was she doing? She was wriggling in! Suddenly, Gretchen was standing in front of the toilet even though the stall door was closed, which meant privacy. Abby’s mind was blown. She stared at this insane girl, waiting to see what she’d do next. Slowly, Gretchen blinked her enormous blue eyes.

“I don’t like horses,” she said. “They smell bad. And I don’t think Margaret Middleton is a nice person.”

That, at least, made some sense to Abby.

“Horses are stupid,” Gretchen continued. “Everyone thinks they’re neat, but their brains are like hamster brains and if you make a loud noise they get scared even though they’re bigger than we are.”

Abby didn’t know what to say to that.

“I don’t know how to skate,” Gretchen said. “But I think peo- ple who like horses should buy dogs instead. Dogs are nice and they’re smaller than horses and they’re smart. But not all dogs.

We have a dog named Max, but he’s dumb. If he barks while he’s running, he falls down.”

Abby was starting to feel uncomfortable. What if someone came in and saw this weird person standing in the stall with her? She knew she had to say something, but there was only one thing on her mind, so she said it: “I wish you weren’t here.”

“I know,” Gretchen nodded. “My mom wanted me to go to Margaret Middleton’s.”

“Then why didn’t you?” Abby asked. “You invited me first,”Gretchen said. A lightning bolt split Abby’s skull in two. Exactly! This was what she had been saying. Her invitation had been first! Everyone should be HERE with HER because she had invited them FIRST and Margaret Middleton COPIED her. This girl had the right idea.

Maybe everything wasn’t ruined. Maybe Abby could show this weirdo how good she was at skating, and she’d tell everyone at school. They’d all want to see, but she’d never have another birth- day party again, so they’d never see her skate unless they begged her to do it in front of the whole school, and then she might do it and blow everyone’s minds, but only if they begged her a lot. She had to start by impressing this girl and that wouldn’t be hard. This girl didn’t even know how to skate.

“I’ll teach you how to skate if you want,” Abby said. “I’m really good.”

“You are?” Gretchen asked. Abby nodded. Someone was finally taking her seriously. “I’m really good,” she said. After Abby’s dad rented skates, Abby taught Gretchen how to lace them super tight and helped her walk across the carpet, show- ing her how to pick up her feet high so she wouldn’t trip. Abby led Gretchen to the baby skate zone and taught her some basic turns, but after a few minutes she was dying to strut her stuff. “You want to go in the big rink?”Abby asked. Gretchen shook her head. “It’s not scary if I stay with you,”Abby said. “I won’t let anything bad happen.” Gretchen thought about it for a minute. “Will you hold my hands?” Abby grabbed Gretchen’s hands and pulled her onto the floor just as the announcer said it was Free Skate, and suddenly the rink was full of teenagers whizzing past them at warp speed. One boy lifted a girl by the waist in the middle of the floor and they spun around and the DJ turned on the mirror ball and stars were gliding over everything, and the whole world was spinning. Gretchen was flinching as speed demons tore past, so Abby turned around and backskated in front of her, pulling her by both soft, sweaty hands, merging them into the flow. They started skating faster, taking the first turn, then faster, and Gretchen lifted one leg off the floor and pushed, and then the other, and then they were actually skating, and that’s when the drums started and Abby’s heart kicked off and the piano and the guitar started banging and “We Got the Beat” came roaring over the PA. The lights hitting the mirror ball pulsed and they were spinning with the crowd, orbiting around the couple in the center of the floor, and they had the beat.

Freedom people marching on their feet Stallone time just walking in the street They won’t go where they don't know But they’re walking in line

We got the beat! We got the beat!

Abby had the lyrics 100 percent wrong, but it didn’t matter. She knew, more than she had ever known anything in her entire life, that she and Gretchen were the ones the Go-Go’s were singing about. They had the beat! To anyone else watching, they were two kids going around the rink in a slow circle, taking the corners wide while all the other skaters zoomed past, but that’s not what was happening. For Abby, the world was a Day-Glo Electric Wonderland full of hot pink lights, and neon green lights, and turquoise lights, and magenta lights, and they were flashing on and off with every beat of the music and everyone was dancing and they were flying so fast their skates were barely touching the ground, sliding around corners, picking up speed, and their hearts beat with the drums, and Gretchen had come to Abby’s birthday party because Abby had invited her first and Abby had a real E.T. poster and now they could eat the entire cake all by themselves.

And somehow Gretchen knew exactly what Abby was think- ing. She was smiling back at Abby, and Abby didn’t want anyone else at her birthday party now, because her heart was beating in time with the music and they were spinning and Gretchen shouted out loud:

“This! Is! Awesome!”

Then Abby skated into Tommy Cox, got tangled up in his legs, and landed on her face, driving her top tooth through her lower lip and spraying a big bib of blood all down her E.T. shirt. Her parents had to drive her to the emergency room, where Abby received three stitches. At some point, Gretchen’s parents retrieved their daughter from the roller rink, and Abby didn’t see her again until homeroom on Monday.

That morning, her face was tighter than a balloon ready to burst. Abby walked into homeroom early, trying not to move her swollen lips, and the first thing she heard was Margaret Middleton.

“I don’t understand why you didn’t come,” Margaret snipped, and Abby saw her looming over Gretchen’s desk. “Everyone was there. They all stayed late. Are you scared of horses?”

Gretchen sat meekly in her chair, head lowered, hair trailing on her desk. Lanie Ott stood by Margaret’s side, helping her berate Gretchen.

“I rode a horse and it took a high jump twice,” Lanie Ott said. Then the two of them saw Abby standing in the door. “Ew,”Margaret said. “What happened to your face? It looks like barf.” Abby was paralyzed by the righteous anger welling up inside her. She had been to the emergency room! And now they were being mean about it? Not knowing what else to do, Abby tried telling the truth.

“Tommy Cox skated into me and I had to get stitches.”

At the mention of Tommy Cox’s name, Lanie Ott opened and closed her mouth uselessly, but Margaret was made of sterner stuff. “He did not,” she said. And Abby realized that, oh my God, Margaret could just say Abby was a liar and no one would ever believe her. Margaret continued, “It’s not nice to lie and it’s rude to ignore other people’s invitations. You’re rude. You’re both rude.” That’s when Gretchen snapped her head up. “Abby’s invitation was first,” she said, eyes blazing. “So you’re the rude one. And she’s not a liar. I saw it.” “Then you’re both liars,”Margaret said. Someone was reaching over Abby’s shoulder and knocking on the open door. “Hey, any of you little dudes know where—aw, hey, sweetness.” Tommy Cox was standing three inches behind Abby, his curly blond hair tumbling around his face. The top button of his shirt was undone to show a gleaming puka shell necklace, and he was smiling with his impossibly white teeth. Heavy gravity was coming off his body in waves and washing over Abby.

Her heart stopped beating. Everyone’s hearts stopped beating.

“Dang,” he said, furrowing his brow and examining Abby’s lower lip. “Did I do that?”

No one had ever looked so closely at Abby’s face before, let alone the coolest senior at Albemarle Academy. She managed to nod.

“Gnarly,” he said. “Does it hurt?” “A little?”Abby managed to say. He looked unhappy, so she changed her mind. “No biggie,”she squeaked. Tommy Cox smiled and Abby almost fell down. She had said something that made Tommy Cox smile. It was like having a superpower.

“Coolness,” he said. Then he held out a can of Coke, conden- sation beading on the surface. “It’s cold. For your face, right?”

Abby hesitated then took the Coke. You weren’t allowed to go to the vending machines until seventh grade, and Tommy Cox had gone to the vending machines for Abby and bought her a Coke.

“Coolness,” she said.

“Excuse me, Mr. Cox,” Mrs. Link said, pushing through the door. “You need to find your way back to the upper school build- ing before you get a demerit.”

Mrs. Link stomped to her desk and threw down her bag. Everyone was still staring at Tommy Cox.

“Sure thing, Mrs. L,” he said. Then he held up a hand. “Gimme some skin, tough chick.”

In slow motion Abby gave him five. His hand was cool and strong and warm and hard but soft. Then he turned to go, took a step, looked back over his shoulder, and winked.

“Stay chill, little Betty,” he said. Everyone heard it. Abby turned to Gretchen and smiled and her stitches ripped and her mouth filled with salt. But it was worth it when she turned and saw Margaret Middleton standing there like a dummy with no comeback and nothing to say. They didn’t know it then, but that’s when everything started, right there in Mrs. Link’s home- room: Abby grinning at Gretchen with big blood-stained teeth, and Gretchen smiling back shyly.

THAT’S WHAT FRIENDS ARE FOR

Abby took that Coke can home and never opened it. Her lip healed and the stitches came out a week later, leaving an ugly fruit jam scab that Hunter Prioleaux said was VD but that Gretchen never even mentioned.

As her scab was healing, Abby decided there was no way her new friend hadn’t seen E.T. Everyone had seen E.T. And so one day she confronted Gretchen in the cafeteria.

“I haven’t seen E.T.,” Gretchen repeated.

“That’s impossible,” Abby said. “60 Minutes says even the Russians have seen E.T.”

Gretchen stirred her lima beans and then made up her mind about something.

“You promise not to tell anyone?” she asked. “Okay,”Abby said. Gretchen leaned in close, the tips of her long blond hair trailing across her Salisbury steak. “My parents are in the Witness Protection Program,”she whispered. “If I go to the movies, I might get kidnapped.” Abby was thrilled. Gretchen would be her dangerous friend!

Life was finally getting exciting. There was only one problem: “Then how could you come to my birthday party?” she asked. “My mom thought it would be okay,” Gretchen said. “They don’t want being criminals to keep me from having a normal life.” “Then ask her if you can see E.T.,” Abby said, getting back to the important subject. “If you want to have a normal life, you have to see E.T. People are going to think you’re weird if you don’t.” Gretchen sucked the gravy off the tips of her hair and nodded. “Okay,” she said. “But your parents will have to take me. If my parents and I are seen in public together, a criminal might recognize them.”

Abby exhausted her parents into agreement, despite the fact that her mom believed seeing a movie more than once was a waste of time, money, and brain cells. The next weekend, Mr. and Mrs. Rivers dropped off Abby and Gretchen at Citadel Mall to see the 2:20 showing of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial while they went Christmas shopping. Because she lived a sheltered life in the Witness Protection Program, Gretchen was clueless about how to buy tickets or popcorn. It turned out she’d never even been to a movie on her own before, which was bizarre to Abby, who could ride her bike to the Mt. Pleasant 1–2–3 and see the $1 afternoon matinees. Gretchen may have had criminals for parents, but Abby felt a lot more worldly.

The lights went down and at first Abby was worried she wouldn’t love E.T. as much as all the other times she’d seen it, but then Elliott called Michael penis-breath and she laughed and the government came and Elliott reached for E.T. through the plastic wall and she cried, reminding herself once more that this was the most powerful motion picture in the world. But as Elliott and Michael stole the van right before the big chase at the end, Abby had a horrible thought: What if Gretchen wasn’t crying? What if the lights came on and Gretchen was sitting there sucking on her braids like this was an ordinary movie? What if she hated it?

These thoughts were so stressful, they kept Abby from enjoy- ing the ending. As the credits rolled, she sat in the dark, miserable, staring straight ahead, too scared to look at Gretchen. Finally, she couldn’t stand it anymore, and as the credits thanked Marin County for its assistance she turned her head and saw Gretchen staring at the screen, her face totally blank. Abby’s heart cramped and then, before she said anything, she saw the light from the screen reflecting off Gretchen’s wet cheeks, and Abby’s heart unclenched and Gretchen turned to her and said, “Can we see it again?”

They could. Then they had dinner at Chi-Chi’s and Abby’s dad pretended it was his birthday and the waiters came out and put a giant sombrero on his head and sang him the Mexican birthday song and gave them all fried ice cream.

It was the greatest day of Abby’s life.

————————————

“I have to tell you something serious,” Gretchen said. It was the second time she’d slept over. Abby’s parents were out at a Christmas party, and so the two of them had eaten frozen pizzas during The Powers of Matthew Star and now Falcon Crest had just ended. Falcon Crest wasn’t as good as Dynasty, but Dynasty came on Wednesday nights, a school night, so Abby wasn’t allowed to watch it. Gretchen wasn’t allowed to watch anything. Her parents had strict TV rules, and they didn’t even have cable because it was too dangerous to have their names on the bill. Three weeks into their friendship and Abby was used to all the strange rules of the Witness Protection Program. No movies, no cable, barely any TV, no rock music, no two-piece swimsuits, no sugary breakfast cereals. But there was something Abby knew about the Witness Protection Program from movies, and it scared her: sometimes, with no warning, the people under protection disappeared overnight.

And now that Gretchen had something important to say, Abby knew exactly what it was.

“You’re moving,” she said. “Why?”Gretchen asked. “Because of your parents,”Abby said. Gretchen shook her head. “I’m not moving,”she said. “You can’t hate me. You have to promise not to hate me.” “I don’t hate you,”Abby said. “You’re cool.” Gretchen kept picking at the plaid sofa, not looking at Abby, and Abby started getting worried. She didn’t have a lot of friends, and Gretchen was definitely the coolest person she’d ever met, after Tommy Cox.

“My parents aren’t really in the Witness Protection Program,” Gretchen said, clenching her hands in her lap. “I made it up. They won’t let me see PG- or R-rated movies. They’ll only let me see G-rated movies until I’m thirteen. I didn’t tell them I was going to E.T. I told them we went to see Heidi’s Song instead.”

There was a long silence. Tears slipped down her nose and dripped onto the sofa.

“You hate me,” Gretchen said, nodding to herself.

Actually, Abby was thrilled. She’d never totally believed the whole Witness Protection Program story anyway because, like her mom said, if something seemed too good to be true then it probably was. And if Gretchen’s parents treated her like a baby, that made Abby the cool one. Gretchen needed her if she was ever going to see a PG movie or keep up with Falcon Crest, so they’d al- ways have to be friends. But Abby also knew that Gretchen might stop being her friend now that Abby knew a secret about her, so she decided to give her a secret back. “You want to see something gross?”she asked. Tears splatted onto the couch as Gretchen shook her head. “I mean really gross,”Abby explained. Gretchen kept crying, clenching her hands until her knuckles turned white. So Abby got a flashlight out of the kitchen drawer, pulled Gretchen off the sofa, and forced her upstairs into her par- ents’ bedroom, listening for their car pulling into the driveway the entire time.

“We shouldn’t be in here,” Gretchen said in the dark.

“Shhhh,” Abby said, leading her past the trunk at the foot of the bed and into her dad’s closet. Inside, behind his pants, there was a suitcase. Inside the suitcase was a black plastic bag, and inside the black plastic bag was a big cardboard box containing a videotape. Abby switched on the flashlight and shone it on the VHS box.

“Bad Mama Jama,” she said. “My mom doesn’t know he has it.”

Gretchen wiped her nose on her sleeve and took the box from Abby with both hands. On the front cover, an extremely large black woman was bent over, dressed in nothing but a string bi- kini, spreading her fanny wide open. She was looking back over her shoulder, wearing orange lipstick that matched her nail polish, smiling like she was thrilled two little girls were looking up her butt. The caption under the photo read: “Mama’s got supper in the oven!”

“Ew!” Gretchen squealed, throwing the tape at Abby. “I don’t want it!”Abby shouted, throwing it back at her. “It touched me!”Gretchen said. Abby wrestled her onto the bed and straddled Gretchen’s squirming body, rubbing the tape all over her hair.

“Ew! Ew! Ew!” Gretchen screamed. “I’m going to die!” “You’re going to get pregnant!” Abby said. That was the moment. When Gretchen stopped lying to

Abby about the Witness Protection Program, when Abby showed Gretchen her dad’s secret sex fetish for large black women, when Abby wrestled with Gretchen on her parents’ bed. Starting that night, they were best friends.

————————————

Everything happened over the next six years. Nothing happened over the next six years. In fifth grade they had separate homerooms, but over lunch Abby told Gretchen everything that had happened on Remington Steele and The Facts of Life. Gretchen wanted Mrs. Garrett to be her mom, Abby thought Blair was usu- ally right about everything, and they both wanted to grow up to run their own private detective agency where Pierce Brosnan had to do whatever they said.

Gretchen’s mom got a speeding ticket with the girls in the car and said “Shit” out loud. To bribe them into not telling Mr. Lang, she took them to the Swatch store downtown and bought them brand new Swatch watches. Abby got a Jelly and used her own money to get one green and one pink Swatch guard that she twisted together; Gretchen got a Tennis Stripe and matching green and pink Swatch guards. After playing outside, they’d sniff each other’s watch bands and try to figure out what they smelled like. Abby said hers smelled like honeysuckle and cinnamon and Gretchen’s smelled like hibiscus and rose, but Gretchen said they both just smelled like sweat.

Gretchen slept over six times at Abby’s house in Creekside before Abby was finally allowed to spend the night at Gretchen’s house in the Old Village, the la-di-da part of Mt. Pleasant where all the houses were dignified and either overlooked the water or had enormous yards, and if anyone saw a black person walking down the street who wasn’t Mr. Little, they would pull their Volvo over and ask if he was lost.

Abby loved going to Gretchen’s. The Langs’ house sat on Pierates Cruze, a dirt road shaped like a horseshoe where the house numbers went in the wrong order and the street name was spelled wrong because rich people could do whatever they wanted. Their house was number eight. It was an enormous gray cube that looked out over Charleston harbor through a back wall that was a two-story high window made of a single sheet of glass. Inside, it was as sterile as an operating theater, all hard right angles, sheer surfaces, gleaming steel, and glass that was polished twice a day. It was the only house in the Old Village that looked like it was built in the twentieth century.

The Langs had a dock where Abby and Gretchen swam (as long as they wore tennis shoes so they wouldn’t cut their feet on oysters). Mrs. Lang cleaned Gretchen’s room every other week and threw out anything she didn’t think her daughter needed. One of her rules was that Gretchen could have only six magazines and five books at a time. “Once you’ve finish reading it, you’ve finished needing it” was her motto.

So Abby got all the books that Gretchen bought at B. Dalton’s with her seemingly unlimited allowance. Forever . . . by Judy Blume, which they knew was all about them (except for the gross parts at the end). Jacob Have I Loved (secretly Abby believed that Gretchen was Caroline and she was Louise). Z for Zachariah (which gave Gretchen nuclear war nightmares), and the ones they had to sneak into the Langs’ house hidden in the bottom of Abby’s bookbag, all of them by V. C. Andrews: Flowers in the Attic, Petals in the Wind, If There Be Thorns, and, most scandalous of them all, My Sweet Audrina, with its endless parade of sexual perversion.

But mostly, for six years, they stayed in Gretchen’s room. They made endless lists: their best friends, their okay friends, their worst enemies, the best teachers and the meanest teachers, which teachers should get married to each other, which school bathroom was their favorite, where they would be living in six years, in six months, in six weeks, where they’d live when they were married, how many babies their cats would have together, what their wedding colors would be, whether Adaire Griffin was a total slut or just misunderstood, whether Hunter Prioleaux’s parents knew their son was the spawn of Satan or if he fooled them, too.

It was an endless Seventeen quiz, an eternal process of self-classification. They traded scrunchies, they pored over YM and Teen and European Travel and Life. They fantasized about Italian counts, and German duchesses, and Diana, Princess of Wales, and summers in Capri, and skiing in the Alps. In their shared fantasies, dark European men were constantly escorting them into helicopters and flying them to hidden mansions where they tamed wild horses.

After they snuck into Flashdance, Abby and Gretchen would slip off their shoes at the dinner table and grab each other’s crotches with sock-covered feet. Abby would wait until Gretchen was lifting a forkful of peas, then stick her foot in Gretchen’s crotch, making her fling food everywhere and sending her dad into a tirade.

“Wasting food is no joke!” he’d shout. “That’s how Karen Carpenter died!”

Gretchen’s parents were uptight Reagan Republicans who spent every Sunday at St. Michael’s downtown, praising God and social climbing. When The Thorn Birds came on, Abby and Gretchen were dying to watch it on the big TV, but Mr. Lang was dubious. He’d heard that the content was questionable.

“Dad,” Gretchen said. “It’s just like The Winds of War. It’s basically a sequel.”

Herman Wouk’s dry-as-dust, fourteen-hour miniseries about World War II was Mr. Lang’s favorite television event of all time, so invoking its name meant they automatically received his blessing. While they were watching episode one of The Thorn Birds, he came home and stood in the door of the TV room long enough to realize that this was no Winds of War. His face turned dark red. Abby and Gretchen were too caught up in the steamy Outback love scenes to notice, but sixty seconds after he left the room, Mrs. Lang came in and turned off the TV. Then she marched them into the living room for a lecture.

“The Roman church can glorify foul language and half-naked priests rutting like animals,” Mr. Lang told them. “But not in this house. Now, there’s no more television tonight and I want you girls to go upstairs and wash your hands. Your mother’s got supper in the oven.”

Halfway up the stairs, they couldn’t hold it in anymore and Abby laughed so hard she peed.

————————————

Sixth grade was the bad year. After he’d gone on strike back in ’81, Abby’s dad had lost his job as an air traffic controller and been hired as assistant manager at a carpet cleaner. Eventually they had cutbacks, too. The Rivers family had to sell their place in Creekside and move into a sagging house on Rifle Range Road. Four giant pine trees loomed over their brick shoebox and showered it with spider webs and sap while completely blocking out the sun. That was when Abby stopped inviting Gretchen over to spend the night and started inviting herself over to the Langs’ house every weekend. Then she started showing up on weeknights, too. “You’re always welcome here,” Mr. Lang said. “We think of you as our other daughter.” Abby had never felt so safe. She started leaving her pajamas and a toothbrush in Gretchen’s room. She would have moved in if they’d let her. Their house always smelled like air-conditioning and carpet shampoo. Her house had gotten wet a long time ago and never dried. Winter or summer, it stank of mold.

In 1984, Gretchen got braces, and Abby got politics when Walter Mondale declared Geraldine Ferraro his running mate. It never occurred to Abby that anyone could possibly object to electing the first female vice president, and her parents were too caught up in their own economic drama to notice when she put a Mondale/Ferraro bumper sticker on their car. Then she put one on Mrs. Lang’s Volvo.

She and Gretchen were in the TV room watching Silver Spoons when Mr. Lang came in after work shaking with rage, the shreds of the bumper sticker waving from one hand. He tried to throw the pieces on the floor, but they stuck to his fingers.

“Who did this?” he demanded, voice tight, face red behind his beard. “Who? Who?”

That’s when Abby knew she was going to get expelled from the Langs’ house forever. Without even realizing it, she’d committed the greatest sin of all and made Mr. Lang look like a Democrat. But before Abby could confess and accept her exile, Gretchen spun around on the couch and drew herself up onto her knees.

“She’ll be the first female vice president ever,” Gretchen said, gripping the back of the sofa with both hands. “Don’t you want me to feel proud of being a woman?” “This family is loyal to the president,”Mr. Lang said. “You’d better hope no one saw that . . . thing on your mother’s car. You’re too young for politics.”

He made Gretchen take a razor blade and peel off the rest of the sticker while Abby watched, terrified she was going to get in trouble. But Gretchen never told. It was the first time Abby had ever seen her fight with her parents.

Then came the Madonna Incident.

For the Langs, Madonna was totally and completely out of the question. But when Gretchen’s dad was at work and her mom was taking one of her nine billion classes (Jazzercise, power walking, book club, wine club, sewing circle, women’s prayer circle), Gretchen and Abby would dress up like the Material Girl and sing into the mirror. Gretchen’s mom had a jewelry box devoted entirely to crosses, so it was basically like she was inviting them to do it.

With dozens of crosses strung around their necks, they stood in front of Gretchen’s bathroom mirror and teased their hair big, tying huge floppy bows in it, cutting the arms off of T-shirts, painting their lips bright coral, shadowing their eyes bright blue, dropping makeup on the white wall-to-wall carpet and accidentally stepping on it, holding up a hair brush and a curling iron as microphones and singing along to the “Like a Virgin” Cassingle on Gretchen’s peach boombox.

Abby had just decided to draw on a beauty spot and was hunting for eyeliner in the makeup carnage on the counter while Gretchen was singing “Like a vir-ir-ir-ir-gin/With your heartbeat/ Next to mine . . .” when suddenly Gretchen’s head was yanked backward and Mrs. Lang was between them, tearing the bow out of her daughter’s hair. The music was so loud, they hadn’t heard her come home.

“I buy you nice things!” she screamed. “This is what you do?”

Abby stood there stupidly while the Cassingle looped and Gretchen’s mom chased her daughter between the twin beds, hitting her with a hairbrush. Abby was terrified that Mrs. Lang would notice her, and a part of her brain knew she should hide, but she simply stood there like a dummy as Mrs. Lang followed Gretchen down to the ground between the two beds. Gretchen curled up on the carpet, making a high-pitched sound, while Madonna sang, “You’re so fine, and you’re mine/I’ll be yours/Till the end of time . . .” and Mrs. Lang’s arm worked up and down, raining blows on Gretchen’s legs and shoulders.

“Make me strong/Yeah, you make me bold . . . ,” Madonna sang.

Gretchen’s mom walked to the boombox and jammed down on the buttons, prying open the door and yanking out the Cassingle while it was still playing, leaving big loops of magnetic tape drool- ing everywhere. In the sudden silence, Abby heard the motor whine as the gears jammed. The only other sound was Mrs. Lang breathing hard.

“Clean up this mess,” she said. “Your father will be home.” Then she stormed out and slammed the door. Abby crawled across the bed and looked down on the floor at

Gretchen. She wasn’t even crying. “Are you okay?”Abby asked. Gretchen raised her head and looked at her bedroom door. “I’m going to kill her,”she whispered. Then she wiped her nose and looked up at Abby. “Don’t ever tell I said that.” Abby remembered a day the summer before when she and Gretchen had tiptoed into Gretchen’s parents’room and opened the drawer on her dad’s bedside table. Lying inside, under an old issue of Reader’s Digest, was a stubby black revolver. Gretchen took it out and pointed it at Abby and then at the pillows on the bed, first one, then the other.

“Bang . . .” she whispered. “Bang.”

Abby remembered those whispered “bangs,” and now she looked at Gretchen’s dry eyes and she knew that something was happening that was truly dangerous. But she never told. Instead, she helped Gretchen clean up, then she called her mom and asked her to come pick her up. Whatever else happened that night when Gretchen’s dad got home, Gretchen never talked about it.

A few weeks later it had all blown over, and the Langs took Abby with them to Jamaica for a ten-day vacation. She and Gretchen got cornrows in their hair that clicked everywhere they walked. Abby got sunburned. They played Uno every night and Abby won almost every game.

“You’re a card sharp,” Gretchen’s dad said. “I can’t believe my daughter brought a card sharp into our family.”

Abby ate shark for the first time. It tasted like steak made out of fish. They had their first big fight because Abby kept playing Weird Al’s “Eat It” on the cassette player in their room, until the second to the last day when she found pink nail polish spilled all over her tape.

“I’m sorry,” Gretchen said, enunciating each word like she was royalty. “It was an accident.”

“It was not,” Abby said. “You’re selfish. I’m the fun one, and you’re the mean one.”

They were always trying to figure out which one of them was which. Recently, Abby had been designated the fun one and Gretchen the beautiful one. Neither of them had ever been the mean one before.

“You just tag along with my family because you’re poor,” Gretchen snapped back. “God, I’m sick of you.” Gretchen’s braces hurt all the time and Abby’s braids were too tight and gave her headaches. “You know which one you are?” Gretchen asked. “You’re the dumb one. You play that stupid song like it’s cool, but it’s for little kids. It’s immature, and I don’t want to hear it any- more. It’s stupid. It makes YOU stupid.”

Abby locked herself in the bathroom, and Gretchen’s mom had to coax her out for supper, which she ate alone on the balcony while the bugs chewed her up. That night, after the lights went out, she felt someone crawl into her bed, and Gretchen slid up next to her.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered, filling Abby’s ear with her hot breath. “I’m the stupid one. You’re the cool one. Please don’t be mad at me, Abby. You’re my best friend.”

————————————

Seventh grade was the year of their first slow-dance make-out par- ty, and Abby tongue-kissed Hunter Prioleaux as they rocked back and forth to “Time after Time.” His enormous stomach was hard- er than she thought it would be and he tasted like Big League Chew and Coke, but he was also really sweaty and smelled like burps. He followed Abby around for the rest of the night trying to get to third base, until she hid in the bathroom while Gretchen ran him off.

Then came a day that changed Abby’s life forever. She and Gretchen were returning their lunch trays, talking about how they needed to stop getting hot lunch like little kids and start bringing healthy food to school so they could eat outside with everyone else, when they saw Glee Wanamaker standing by the tray window, hands twisting, her fingers squirming and pulling at each other, eyes red and shining, staring into the big garbage can. She’d put her retainer on her tray and then dumped it in the trash, and now she wasn’t sure which garbage bag it was in.

“I’ll have to look in all of them,” she sobbed. “This is my third retainer. My dad’s going to kill me.”

Abby wanted to go but Gretchen insisted they help, and so William, the head of the lunch room, took them out back and showed them the eight bulging black plastic bags full of warm milk, half-eaten pizza squares, fruit cocktail, melted ice cream, wet shoestring fries, and curdled ketchup. It was April and the sun had been cooking the bags into a rank stew. It was the worst thing Abby had ever smelled.

She didn’t know why they were helping Glee. Abby didn’t have a retainer. She didn’t even have braces. Everyone else did, but her parents wouldn’t pay for them. They wouldn’t pay for much of anything, and she had to wear the same navy corduroy skirt twice a week, and her two white shirts were turning transparent because she washed them so much. Abby did her own laundry because her mom worked as a home nurse.

“I do laundry for other people all day,” Abby’s mom told her. “Your arms aren’t broken. Pull your weight.”

Her dad had been working as the dairy department manager at Family Dollar, but they let him go because he accidentally stocked a bunch of expired milk. He’d put up a sign at Randy’s Model Shop to do small engine repairs on people’s remote control planes, but after customers complained that he was too slow, Randy made him take down the sign. Now he had a sign up at the Oasis gas station on Coleman Boulevard saying he’d fix any lawn mower for $20. He had pretty much stopped talking, and he’d started filling their yard with broken lawn mowers.

Abby was beginning to feel like everything was too much. She was beginning to feel like nothing she did made any difference.

She was beginning to feel like her family was sliding down a hill and they were dragging her down after them and at the bottom of that hill was a cliff. She was beginning to feel like every test was a life-or-death challenge and if she failed even one of them, she’d lose her scholarship and get yanked out of Albemarle and never see Gretchen again.

And now she stood behind the cafeteria in front of eight steaming bags of fresh garbage, and she wanted to cry. Why was she the one helping Glee, whose dad was a stockbroker? Why wasn’t anyone helping her? She never knew what caused it, but at that moment, Abby changed. Something inside her head went “click” and the next second she was thinking differently.

She didn’t have to be poor. She could get a job. She didn’t have to help Glee. But she could. She could decide how she was going to be. She had a choice. Life could be an endless series of joyless chores, or she could get totally pumped and make it fun. There were bad things, and there were good things, but she got to choose which things to focus on. Her mom focused only on the bad things. Abby didn’t have to.

Standing there behind the cafeteria in the stink of an entire school’s worth of putrid garbage, Abby felt the channels change, the world brighten as the sunglasses came off her brain. She turned to Gretchen and said, “Mama’s got supper in the oven!”

Then she untied the nearest bag, took out a slice of half-chewed pizza, and frisbeed it onto the roof before plunging elbow-deep into an ocean of greasy, slimy, used food. By the time they found Glee’s retainer, strings of congealed cheese stuck in their hair, gobs of fruit cocktail stuck to their shirts, they were laughing like maniacs, throwing handfuls of limp lettuce at one another and flicking French fries against the wall.

————————————

Eighth grade was the year of Max Headroom and Spuds Mackenzie. The year that Abby’s dad started watching Saturday morning car- toons for hours and sleeping on a cot in his shed in the backyard. It was the year that Abby got Gretchen to sneak out of her house so they could ride bikes across the Ben Sawyer Bridge to Sullivan’s Island. Halley’s Comet was passing and everyone had gone to the beach in the middle of the night to see it. They found a deserted spot and lay on their backs in the cold sand, looking up at millions of stars.

“So let me get this straight,” Gretchen said in the dark. “It’s a dirty snowball shaped like a peanut floating through space and that’s why everyone’s so excited?”

Gretchen was not very romantic about science.

“It only comes around once every seventy-five years,” Abby said, straining to see if the speck of light she saw was moving or if she was only imagining it. “We might never see it again.”

“Good,” Gretchen said. “Because I’m freezing and I have sand in my underwear.”

“Do you think we’ll still be friends the next time it comes around?” Abby asked.

“I think we’ll be dead,” Gretchen said.

Abby did the math in her head and realized they’d be eighty- eight years old.

“People are going to live longer in the future,” she said. “We might still be alive.”

“But we won’t know how to set the clocks on our VCRs and we’ll be old and hate young people and vote Republican like my parents,” Gretchen said.

They had just rented The Breakfast Club, and turning into adults felt like the worst thing ever.

“We won’t wind up like them,” Abby said. “We don’t have to be boring.”

“If I stop being happy, will you kill me?” Gretchen asked. “Totally,” Abby said. “Seriously,”Gretchen said. “You’re the only reason I’m not crazy.” They were quiet for a moment. “Who said you’re not crazy?”Abby asked. Gretchen hit her. “Promise me you’ll always be my friend,”she said. “DBNQ,”Abby replied. It was their shorthand for “I love you.”Dearly But Not Queerly. And they lay there on the freezing sand and felt the earth turn

beneath their backs, and they shivered together as the wind blew off the water, and a frozen ball of ice passed by their planet, three million miles away in the cold distant darkness of deep space.

PARTY ALL THE TIME

“You guys want to freak the fuck out?” Margaret Middleton asked.

Blood-warm water slopped against the hull of the Boston Whaler. It had been quiet for almost an hour as the four girls drift- ed in the creek; Bob Marley played low on the boombox, their eyes closed, legs up, sun warm, heads nodding. They’d been waterski- ing on Wadmalaw, but after Gretchen wiped out hard, Margaret cruised them into an inlet, cut the engine, dropped the anchor, and let them float. For an hour, the loudest sounds were the occasional spark of a lighter as someone lit a Merit Menthol or the ripe pop as someone cracked a lukewarm Busch. Underneath it all was the endless hiss of marsh grass rustling in the wind.

Abby faded up from her nap to see Glee rattling a beer out of the cooler. Glee made her “Want one?” face and Abby stretched out an arm, dried salt cracking on her skin, and took a slug of the warm watery wonderful Busch. It was their drink of choice, mostly because the old lady who ran Mitchell’s would sell them a case for forty dollars without asking for ID.

Abby was overflowing with a sense of belonging. Out here, there was nothing to worry about. They didn’t have to talk. They didn’t have to impress anyone. They could fall asleep in front of one another. The real world was far away.

The four of them were best friends, and while some of the kids called them bops, or mall maggots, or Debbie Debutantes, the four of them didn’t give a tiddly-fuck. Gretchen was number two in their class, and the other three were in the top ten. Honor roll, National Honor Society, volleyball, community outreach, perfect grades, and, as Hugh Horton once said with great reverence, their shit tasted like candy.

It didn’t come easy. They cared hard. They cared about their clothes, they cared about their hair, they cared about their makeup (Abby especially cared about her makeup), and they cared about their grades. Abby, Gretchen, Glee, and Margaret were going places.

Margaret was sitting in the driver’s seat, legs up on the hydro- slide, blowing out big plumes of mentholated smoke, rich as shit, loaded with old Charleston money, American by birth, Southern by the grace of God. She was Maximum Margaret, a giant blond jock whose sprawling arms and legs took up half the boat. Everything about her was too much: her lips were too red, her hair was too blond, her nose was too crooked, her voice was too loud.

Glee yawned and stretched. The total opposite of Margaret, she was a tiny, tanned girl version of Michael J. Fox who still had to buy her shoes in the children’s department. In the summer her skin turned chestnut and her belly button darkened to black. Her hair was highlighted seven different shades of brown, and despite having a koala nose and sad puppy-dog eyes, she always attracted too much male attention because she’d developed early, and way out of proportion to her height. Glee was also scary smart, a baby yuppie down to the bone. Her little red Saab wasn’t from her dad- dy: she’d made the down payment with money she’d earned on the stock market. The only thing daddy did was put in her trades.

Gretchen lifted her head from where she was lying facedown on a towel in the prow and took a sip of her Busch. Gretchen: treasurer of the student vestry, founder of the Recycling Club, founder of the school’s Amnesty International chapter, and, if the bathroom walls were to believed, the hottest girl in tenth grade. Long, lean, lanky, and blond, she was a Laura Ashley princess in floral print dresses and Esprit tops—a stark contrast to Abby, who barely reached Gretchen’s shoulders and whose big hair and thick makeup made her look like she should be waiting tables in a truck- stop diner. Abby tried very hard not to think about the way she looked, and most days, especially days like this, she succeeded.

As they lit their cigarettes, as they opened their beers, as they came blinking back into the world, Margaret pulled a black plastic film canister out of her bag, held it up, and asked:

“You guys want to freak the fuck out?” “What is it?”Abby asked. “Acid,”Margaret said. Bob Marley suddenly sounded very mellow, indeed. Gretchen twisted around on her towel. “Where’d you get it?” “Stole it from Riley,” Glee lied.

Margaret was the only girl in her enormous family, and her second-oldest brother, Riley, was a notorious burnout who alternated between doing semesters at the College of Knowledge and rehab at Fenwick Hall, where Charleston’s richest alcoholics went to rest. He was famous for slipping drugs into girls’ drinks at the Windjammer, and then, after they passed out, he’d have sex with them in the backseat of his car. It came to an end when one of the girls woke up, broke his nose, and ran down the middle of Ocean Boulevard with no top on, screaming her lungs out. The judge encouraged the girl’s parents not to press charges because Riley came from a fine family and had his whole future ahead of him. Ultimately, all that happened was he was required to live at home for a year. So now he moved between different Middleton houses—from Wadmalaw, to Seabrook, to Sullivan’s Island, to downtown—staying out of reach of his dad, supposedly going to AA meetings but mostly selling drugs.

That said, Riley was a known quantity. If Margaret and Glee told Gretchen where they’d really gotten the acid, she’d never ingest it; and if these girls were going to trip, it would be all of them at once or nobody at all. That’s how they did everything.

“I don’t know,” Gretchen said. “I don’t want to wind up like Syd Barrett.”

Syd Barrett, the original lead singer for Pink Floyd, had done so much acid in the sixties that his brain melted, and now, twenty years later, he lived in his mom’s basement and sometimes, on good days, managed to ride his bike to the post office. He collected stamps. Gretchen believed that if she did acid, it was one hundred percent guaranteed she’d pull a Syd Barrett and never be normal again.

“My brother said Syd put out an album last year but all the songs were about stamp collecting,” Glee said.

“What if that’s me?” Gretchen asked. Margaret blew out a dramatic plume of smoke. “And you don’t collect stamps,”she said. “What the fuck are you going to sing about?” “I’ll do it if you promise to drive all the recycling club’s cans to the recycling center,” Gretchen said to Margaret. Margaret flicked her butt into the creek. “Recycle that, you hippie.” “Glee?”Gretchen asked.

“Those bags leak,” Glee said. “I get wasps in my car.”

Gretchen stood up, raised her arms over her head, and her fingertips brushed the sky.

“As always,” she said. “Thank you for your support.”

Then she stretched out one long leg, stepped off the prow, and dropped into the water without a splash. She didn’t come back up. Big whoop. Gretchen could hold her breath forever and she liked to wallow in the freezing cold at the bottom of the river. That was the good thing about Gretchen. As much as she wanted to save the planet, she was pretty casual about it.

“Tell her where we got it and I’ll break your face,” Margaret said to Abby.

Summer of ’88 had been the most amazing summer ever. It was the summer of “Pour Some Sugar on Me” and “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” and all of Abby’s money went for gas because she’d finally gotten her license and could drive after dark. Every night at 11:06, she and Gretchen popped their screens, slipped out of their win- dows, and just cruised around Charleston. They went night swim- ming at the beach, they hung out with the James Island kids at the Market, they smoked cigarettes in the parking lot in front of the Garden and Gun club and watched Citadel ca-dicks pick fights. One night they’d just driven north on 17, making it almost all the way to Myrtle Beach, smoking an entire pack of Parliaments and listening to Tracy Chapman sing “Fast Car” and “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution” over and over before heading home just as the sun was coming up.

Meanwhile, most of Margaret and Glee’s summer had been spent sitting in Glee’s car waiting for drug deals to materialize. No one except the most maximum mutants in their class had ever done acid, so it was important to Margaret that they be the first normal people to trip; the same as they were the first girls to bring a note to sit out gym class because of their periods, the same as they were the first four to go to a live concert (Cyndi Lauper), the same as they were the first four to get their driving permits (except for Gretchen, who had problems telling her left from her right). Margaret and Glee spent months on the acid project, but every single deal fell apart. Abby started feeling sorry for Glee, and she offered to employ the Dust Bunny on yet another of Margaret’s long drug drives to nowhere. Abby’s offer infuriated both Glee and Margaret.

“Hell, no,” Margaret said. “You are not driving. We went to lower school in a building named after my granddaddy.”

“My father’s firm manages the school’s portfolio,” Glee added.

“If we get busted, we’ll get suspended,” Margaret said. “That’s a free fucking vacation. If you get busted, you’ll get expelled. I’m not being friends with a high school dropout who works at S-Mart.”

As far as Abby was concerned, that was a needlessly nega- tive view of the situation. Yes, she had stayed in school by get- ting a scholarship that came with dozens of strings attached, but Albemarle Academy was definitely not looking for an excuse to get rid of her. Her grades were totally awesome. But you couldn’t argue with Margaret, so instead Abby offered to pay for Glee’s gas and was secretly relieved when Glee turned her down.

Their most recent drug safari had taken Glee and Margaret to the parking lot of a bait shop on Folly Beach, where they sat in Glee’s car for two hours in the pouring rain before Margaret got on the pay phone and discovered that their connection was not simply waiting a crazy long time to signal them. He’d been busted. They went to his room at the Holiday Inn, because what else were they going to do, and discovered that the cops not only had left the door wide open but had also totally failed to find his stash hidden underneath the mattress. Margaret and Glee did not make the same mistake.

Now there’s always a chance that if you find acid hidden un-derneath a mattress in a Holiday Inn, left there by two guys you’ve never met, who were hiding it from the police and who are now in jail, it might be spiked with strychnine or something worse. But there was also a chance that it might not be spiked with strychnine or something worse, and Abby preferred to look on the bright side.

Gretchen popped up out of the water and spat Margaret’s ciga- rette butt into the boat. It stuck to Margaret’s massive thigh.

“Oh my God,” Margaret said. “How did you even know that’s mine? AIDS!”

Gretchen sprayed a mouthful of water into the boat.

“That’s not how you get AIDS,” she said. “As we all know, you get AIDS by sucking face with Wallace Stoney.”

“He does not have AIDS,” Margaret said. “Duh!”Glee said. “You get cold sores from herpes.”Margaret looked pissed. “What does it taste like?”Gretchen asked, grabbing onto the side of the boat and chinning herself up to look into Margaret’s eyes. “Do his herp lips taste like true love?”

The two of them stared at each other.

“For your information, they’re not cold sores, they’re zits,” Margaret said. “And they taste like Clearasil.”

They laughed and Gretchen pushed herself away from the boat and floated on her back.

“I’ll do it,” she said to the sky. “But you have to promise I won’t get brain damage.”

“You’ve already got brain damage,” Margaret said, jumping into the water, almost flipping the boat, and landing on Gretchen, one arm around her neck, dragging her beneath the surface. They came up sputtering and laughing, hanging onto each other. “Killer!”

They piloted the boat back to Margaret’s dock, the air getting colder as the sun set. Abby wrapped a flapping towel around her shoulders and Gretchen let the wind catch her cheeks and blow them out like a balloon. Three dolphins breached off to port and paced them for a couple hundred yards, then peeled away and headed back out to sea. Margaret made gun fingers and pretend- ed to shoot them. Gretchen and Abby turned and watched them dive and rise, flickering through the waves, disappearing in the distance, as gray as the chop.

They tied up at Margaret’s dock and started lugging the skis up into the backyard, but Gretchen lingered with Abby down by the boat, cupping her elbows.

“Are you going to do it?” she asked. “Hell, yeah,” Abby said. “Are you scared?”she asked. “Hell, yeah,”Abby said.

“So why?”

“Because I want to know if Dark Side of the Moon is actually profound.”

Gretchen didn’t laugh.

“What if it opens the doors of perception and I can’t get them closed again?” Gretchen worried. “What if I can see and hear all the energy on the planet, and then the acid never wears off?”

“I’d visit you in Southern Pines,” Abby said. “And I bet your parents would get, like, the lobotomy wing named after you.”

“That would be choice,” Gretchen agreed.

“It’ll be crazy fun,” Abby said. “We’ll stick together like swim buddies at camp. We’ll be trip buddies.”

Gretchen pulled some strands of hair around to her mouth and sucked salt water off the tips.

“Will you promise to remind me to call my mom tonight?” she asked. “I have to check in at ten.”

“I will make it my mission in life,” Abby vowed. “Cool beans,”Gretchen said. “Let’s go fry my brains.”Together the four of them heaped all their gear into a big pile in the backyard and hosed it down. Then Abby sprayed the hose up Margaret’s butt.

“Cleansing enema!” she yelled.

“You’re confusing me with my mother,” Margaret shouted, running for the safety of the house.

Abby turned on Glee, but Gretchen was crimping the hose. Things were devolving rapidly when Margaret came out on the back porch carrying one of her mother’s silver tea trays.

“Ladies,” she sing-songed. “Tea time.”

They gathered around the tray underneath a live oak. There were four china saucers, each with a little tab of white paper in the middle. Each tiny tab was stamped with the head of a blue unicorn.

“Is that it?” Gretchen asked.

“No, I decided to bring you guys some paper to chew on,” Margaret said. “Doy.”

Glee reached out to poke her tab, but pulled her finger back before she made contact. They all knew you could absorb acid through your skin. There should have been more of a ceremony; they should have showered first or eaten something. Maybe they shouldn’t have been out in the sun all day drinking so much beer. They were doing this all wrong. Abby could feel everyone losing their nerve, herself included, so just as Gretchen was taking a breath to make an excuse, Abby grabbed her tab and popped it in her mouth.

“What’s it taste like?” Gretchen asked. “Nuttin’honey,”Abby said. Margaret took hers, and so did Glee. Then, finally, Gretchen.

“Do we chew it?” she lisped, trying not to move her tongue. “Let it dissolve,” Margaret lisped back. “How long?”Gretchen asked. “Chill, buttmunch,”Margaret lisped around her paralyzed tongue. Abby looked out at the bright orange sunset burning itself off over the marsh and felt something final: she’d taken acid. It was ir- reversibly in her system. No matter what happened now she had to ride this out. The sunset glowed and throbbed on the horizon, and Abby wondered if it would look so vivid if she hadn’t just dropped acid. Reflexively she swallowed the little bit of paper, and that was that: she’d done something that couldn’t be undone, crossed a line that couldn’t be uncrossed. She was terrified.

“Is anyone hearing anything?” Glee asked. “It takes hours to kick in, retard,”Margaret said. “Oh,”Glee said. “So you normally have a pig nose?” “Don’t be mean,”Gretchen said. “I don’t want to have a bad

trip. I really don’t.” “Do y’all remember Mrs. Graves in sixth grade?” Glee asked.

“With the Mickey Mouse stickers?” “That was so bone,”Margaret said. “Y’all got that, right? Her

lecture about how, at Halloween, Satan worshippers drive around giving little kids stickers with Mickey Mouse on them, and when the kids lick the stickers they’re coated in LSD and they have bad trips and kill their parents.”

Gretchen covered Margaret’s mouth with both hands. “Stop . . . talking . . . ,”she said. So they laid around the backyard as it got dark, smoking ciga-

rettes, talking about nice things, like what was up with Maximilian Buskirk’s weird butt and that year’s volleyball schedule, and Glee told them about some new kind of VD she’d read about that Lanie Ott almost definitely had, and they discussed whether they should get Coach Greene an Epilady for her upper lip, and if Father Morgan was Thorn Birds hot, regular hot, or merely teacher hot. And the whole time, all of them were secretly trying to see if their smoke was turning into dragons or if the trees were dancing. None of them wanted to be the last one to hallucinate.

Eventually, they lapsed into a comfortable silence, with only Margaret humming some song she’d heard on the radio while she cracked her toe knuckles.

“Let’s go look at the fireflies,” Gretchen said. “Cool,”Abby said, pushing herself up off the grass. “Oh my God,”Margaret said. “You guys are so queer.” They ran through the yard and into the long grass in the field

between the house and the woods, watching the green lightning bugs hover, butts glowing, as the air turned lavender the way it does when it gets dark in the country. Gretchen ran over to Abby.

“Spin me around,” she said.

Abby grabbed her hands and they spun, heads tipped back, trying to make their trip happen. But when they fell into the grass, they weren’t tripping, just dizzy.

“I don’t want to see Margaret pinch off firefly butts,” Gretchen said. “We should buy the plot next door and turn it into a nature preserve so no one else can ruin the creek.”

“We totally should,” Abby said.

“Look. Stars,” Gretchen said, pointing at the first ones in the dark blue sky. “You have to promise not to ditch me.”

“Stick with me,” Abby said. “I’ll totally be your lysergic sher- pa. Wherever you go, I’m there.”

They held hands in the grass. The two of them had never been shy about touching, even though in fifth grade Hunter Prioleaux had called them homos, but that was because no one had ever loved Hunter Prioleaux.

“I need to tell you—”Gretchen started to say.

Margaret loomed up out of the dark, pinched-off firefly butts smeared into two glowing lines underneath her eyes. “Let’s go in,” she said. “The acid’s coming up!”

Excerpted from MY BEST FRIEND'S EXORCISM by Grady Hendrix. Reprinted with permission from Quirk Books.