Excerpt

Excerpt

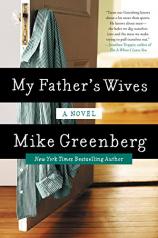

My Father's Wives

I’ve been struck by lightning several times.

Three, to be exact: once in high school, once in college, the last time afterward. None of them was my wife, by the way. You don’t marry the girl who strikes you like lightning, because that doesn’t last forever and you never know what you might be left with when it wears away.

I assume it goes without saying I’m not being literal about the lightning.

I mean it the way they did in The Godfather, when Michael first sees Apollonia: Italian countryside, exotic beauty who doesn’t speak your language. That’s the woman who hits you like lightning but you don’t marry her, because life isn’t in the Italian countryside, life is back in New York, where your brother is riddled with bullets under a tollbooth. And the girl you’ve fallen so hard for can’t drive and doesn’t speak English; good luck with that.

So, I didn’t marry any of the women who struck me like lightning.

The first was when I was seventeen. Her name was Tabitha and she came to my high school after being kicked out of boarding school for sleeping with a teacher. She was gorgeous, flaming red hair and green eyes, and furthermore she was almost entirely unsupervised, coming and going as she pleased in a chauffeured limousine. She was a year behind me in school but light-years ahead in every other way. Long story short: there was a biology class, there were frogs floating stiffly in formaldehyde, she couldn’t bear the smell, I dissected hers, and the next thing I knew we were having sex in the back of her car. It was in that limousine, with my school pants about my knees, that I first felt the lightning.

The second time struck a year later. I was a freshman at college and fell hard for a blond senior named Alyssa, who happened to be engaged to a medical student who lived hundreds of miles away. Alyssa toyed with me for much of the year, flirting, leading me on, allowing me to kiss her occasionally, no doubt driven by loneliness for her man and the pleasure she took in the way I worshipped her. Whatever the reason, I didn’t really mind; I found her so fabulous I was just happy to be around.

Toward the end of the year I was invited by a sorority sister of Alyssa’s to their formal dance and I accepted, even though I knew Alyssa and Phil would be there. I wanted to see them together, to put closure to it for myself.

The party was in the ballroom of a hotel, and several of the girls took a suite upstairs, away from the glaring eye of the university-designated chaperones. I was on a couch in the center of the suite, drinking Heineken from a bottle, while Alyssa seemed fidgety and sad and somewhat sloppily drunk. Then, it happened. When her fiancée got up to use the bathroom, Alyssa was quickly in my face, her nose an inch from mine. Her eyes were stunning—I can still picture them, vivid aquamarine—and despite her drunkenness there wasn’t a streak of red. I could smell the alcohol on her breath too, sweet and fruity, as though she’d been drinking margaritas rather than the beer we had in the suite.

“Am I making you uncomfortable?” she asked breathily.

“A-a-absolutely,” I stammered.

It was the opposite of what I meant to say, but I don’t think she was listening. She just stayed like that for what seemed like an eternity, like time had stopped, her lips so near mine I could taste them, wet and sexy.

Then I heard a flush. The bathroom door opened, and as quickly as she’d come Alyssa was gone, out of my face and out of my life. That was the last time I ever saw her. She and Phil disappeared into one of the bedrooms and didn’t come out the rest of the night. She graduated two weeks later. They were married within the year, and as far as I know they still are. But I can still see her eyes and smell her breath, and feel her lips not quite kissing mine. And when I do, it all looks and smells and feels like lightning.

The third time was in my early twenties with a model named Serena, who had a Jewish doctor for a father and an Indian mother who looked like a princess. The mother was stunning but drank like a fish and swore like a sailor, while her husband was patient and mostly silent, constantly monitoring his pager, ever aware of a pending emergency that never seemed to come.

From this bizarre union sprang Serena: Blue eyes and skin the color of the inside of a malted milk ball. And brilliant. She only modeled part-time; the other part she spent at NYU seeking a postgraduate degree in architectural engineering even though she had no interest in pursuing it. That was her problem, and ultimately her downfall: too many options. Women that beautiful and intelligent have an almost unlimited menu from which to choose, which sounds like a blessing but is often a curse because they can never commit to anything. For every choice they make there is always debilitating uncertainty over the options left on the table.

For a few months, Serena chose me. I vividly remember the first time I saw her, in Sheep Meadow in Central Park; I was playing Ultimate Frisbee, she was lying on a blanket. I chased an errant toss that landed a bit too near her and just as I began to apologize the clouds parted and it was as though the sun shone only on her, like a spotlight. The lightning stopped me in my tracks; I flung the disc back to my group and went immediately to her side. We had lunch and dinner that day and spent the night in her apartment, where in the candlelit stillness of her bedroom I said things so corny they sounded like lines from a movie you would walk out of.

Serena became an obsession. First, in a blissful way—I found myself whistling as I rode the subway. Then in an anxious way. And finally in a way that was just plain horrible. We had nothing in common. I was grounded, career-oriented, bursting with ambition; Serena was just bursting. Nothing satisfied her, not her studies, not her modeling career, and certainly not me. Her wanderlust bordered on maniacal. Once she told me how desperate she was to live in Asia; we were in a water taxi in Venice at the time.

We lived together for just over a year before she moved away, leaving me in her apartment, where I stayed until the lease expired. It was a damn nice place to live and a constant reminder of the great lesson of my youth: Lightning strikes are what they are, brilliant and flashy and electric, but also immediate, gone before the echo fades. To live in the reflection of the light seems exciting but ultimately is not a good idea. You’re much better off finding a safe place and watching the storm through a window.

That’s how I met Claire: Watching a storm through a window.

We were both leaving lunch in the same coffee shop when a sudden rainstorm took us by surprise; we found ourselves together under the awning, staring helplessly into the street. I was about to put my folded newspaper over my head and run three blocks to my office when she caught my eye, long and lean and elegant, hair darker than the black coffee in her Styrofoam cup. I wasn’t struck by lightning. I just knew I wanted to talk to her.

She went back inside the coffee shop to wait out the rain so I did too, took the seat next to her at the counter and ordered coffee. I was trying to think of a witty way to introduce myself when her mobile rang.

“Yes, Liz,” she said in an authoritative tone. “No, I haven’t seen Mandy. I haven’t seen her all week.”

I couldn’t hear the other end of the conversation. Behind the counter was a lot of shouting in Greek, and behind us waitresses snapped at customers to clear the way so they could deliver the omelets and grilled cheese sandwiches people were waiting for impatiently in crowded booths.

“I would love to help you, Liz,” the classy brunette was saying, sounding exasperated, “but I haven’t seen Mandy all week.”

There was a bit more back-and-forth about Mandy, which seemed to make the attractive brunette increasingly annoyed, until she finally just said, “Okay!” and then abruptly hit off on her mobile without saying good-bye. She shook her head and then turned to find me staring at her, completely busting me; in the commotion I had forgotten we didn’t know each other.

She didn’t look put off, though. She just smiled. “I’m sorry if I was talking loudly, it’s so noisy in here. I don’t suppose you’ve seen Mandy, have you?”

“Actually,” I said, “she came and she gave without taking, so I sent her away.”

Her smile grew wider. She had very pretty teeth. “You don’t hear people quote Barry Manilow every day,” she said, and extended her hand. “My name’s Claire.”

We sat at that counter for three hours, long after the rain had faded and the lunch rush waned and all the tables turned over time and again; we sat and chatted and drank the cups of coffee the counterman kept refilling. There was no lightning. Just the opposite; it was as though we had known each other all our lives, two kids who’d grown up together and now met for lunch once a month to catch up. When she finally looked at her watch and said she needed to go, she jotted her phone number on the back of the check and shook my hand. I went to the window and watched her hail a cab. There was something very elegant in the way she moved, the cut of her tan raincoat, the way she slid into the back of the taxi. Clean and classy; as I went back to the counter to grab my briefcase, the sound of her voice echoed in my mind.

I smiled at the counterman. “Guess what, my friend,” I said. “I just met the girl I’m going to marry.”

He didn’t congratulate me, or even smile. He just looked angry. Which I didn’t understand until I looked at the check and saw that it was for one dollar; we had sat for three hours and ordered nothing but coffee. I folded a fifty-dollar bill into the palm of my hand and stuck it out over the counter. “Thanks very much,” I said as we shook hands, “and guess what: you’re going to forget me the minute I walk out that door, but I am going to remember you for the rest of my life.”

It would have made a great line in a movie. Actually, if it had been a movie things would have progressed almost exactly as they did. We had a few dinner dates, she met my mother, I met her parents, then we went to Hawaii and I proposed over a candlelit dinner in a romantic restaurant while she struggled to stay awake, drowsy from anti-seasickness medication. It would have made the perfect cinematic montage, little snippets of a relationship growing and marching forward: the dates, the families, the wedding, the children being born. Then, when the credits finished rolling, the next scene would show the husband boarding a private jet. Just before takeoff, he would take out his iPhone and compose a very brief e-mail.

I came home early. I saw you.

As the jet picked up speed he would sit with his thumb hovering over the send icon. And as the plane lifted off the ground you would hear a voice-over, the husband narrating in a dispassionate voice.

“When I woke up that morning,” he would begin, “my life was perfect.”

Monday

WHEN I WOKE UP that morning, my life was perfect.

My alarm went off at 5:40; I was in my car ten minutes later and drove two miles to the train station, where I have the primo parking space that took years on a waiting list to acquire. It is not a primo parking space, it is the primo parking space; people in this town will be killing each other over it when I die. I got to the gym in Manhattan at quarter past seven and spent forty minutes on an Arc Trainer, watching Angelina Jolie talk about homeless children on the Today show. Then I went up to my office, still in sweat-soaked Under Armour. When my assistant saw me she picked up her phone and ten minutes later there was a toasted bagel, side of low-fat cream cheese, banana, and grande latte on my desk. I didn’t see who delivered it. I was flat on the floor, stretching my lower back, reading the Wall Street Journal.

By nine I was through with the paper, my breakfast, and seventy-three e-mails that required immediate attention. I had also fired off a note to our IT staff to complain about the advertisements for penile enlargement kits that continued to sneak past our firewalls and into my mailbox. “Honestly,” I wrote, “my six-year-old sent me an e-mail in which he said I stink like farts and that got rebuffed, but suggestions for becoming king of my bed by adding inches to my love life seem to be welcome. Can we do something about this?”

Bruce, the CEO of our firm, popped his head in the door just before ten. “What time today?” he asked.

“I’m ready now.”

“Meet you there,” he said, looking down at his tie. “I need to change.”

Five minutes later I was in the elevator. My office is on the sixth floor; the basketball court is on nineteen. It’s a terrific court: an abbreviated full court with regulation baskets on both ends and a three-point arc that stretches over the half-court line. It’s the only place I’ve ever seen where you can play one-on-one on a full court, shooting at different baskets. Bruce designed it himself.

Bruce grew up playing ball in the city, just like I did. We figured that out in China the beginning of last year. Michael Jordan happened to be there at the same time, and his picture was on the cover of every newspaper. On the third day of our trip, Bruce looked at me and said: “I really feel like playing ball.” We went out, bought sneakers, and asked the concierge to find us a court; we played two hours of one-onone in a dusty elementary school gymnasium in Shanghai. It was a great day, for two reasons. First, it got me motivated to get back into shape. Second, and I guess more important, from that day on Bruce never went anywhere without me.

Since China we’ve played nearly every day that we are both in the office. Bruce is eleven years older than I am but he’s still quick, and stronger than me and about four inches taller. But I can shoot the ball. Always could. Wake me up from a dead sleep and I can drain a sixteen-foot jump shot. When they tell you they can teach you to shoot they are lying; they can teach you the proper form, but either you can shoot or you can’t, and if you can’t then LeBron James could coach you and you’d never get really good. Bruce is a lousy shooter but he goes hard on the court; playing with him is about the best workout you’ll ever have.

When we were done I went into the men’s room, pulled my top over my head, and wrung it out into the sink. I loved the way I looked in the mirror. I hadn’t been in this kind of shape since college. I took a shower and put on a navy suit, blue shirt, and lavender tie, then I went back to my office to talk to my kids. My daughter is nine, my son six. I have pictures of each of them facing me at my desk and almost every day I chat with them. I often don’t see them at all during the week, even though we all sleep in the same house, because I leave too early and get home too late. Sometimes I catch Phoebe still stirring, so I kick off my shoes and get into her bed and she tells me stories about her day and her friends and her dance class and the tooth she is on the verge of losing and the type of dog she’s decided she wants and the funny thing Drake said to Josh on television. Then she falls asleep on me, and I stroke her hair and watch her lips shudder and part, shudder and part. I seldom catch Andrew awake, but I love to go into his room and marvel at the impossible positions he manages to twist his body into beneath the covers. I swear, the child has never once slept a night vertically in his bed; he is always at some varying degree of diagonal, his arms splayed in one direction and his legs another. It always makes me laugh, no matter how long my day has been.

I miss them terribly during the week and I find that talking to them on the phone only makes it worse, so most days I speak to their photographs. That day, for instance, I recall saying something to Phoebe about how much I liked the dance number she was working on for the talent show, and I told Andrew how proud I was that he had dropped the bat halfway to first base in his T-ball game, which was a marked improvement from the previous time when he nearly decapitated an umpire. They are perfect, my kids. At least I think they are.

Now it was noon and the distant ache that talking to the pictures usually soothes was instead growing. I had been traveling too much of late; that goes along with being hoops buddies with the CEO. And we were going back to San Francisco that night, another night away, without even the pictures to talk to. So I decided to go home early, which I never do, but the hell with it; I needed to see the kids.

I had to sprint through Grand Central Station to catch the 12:37. I made my way to the bar car and ordered two beers, then stretched out and popped one open. I was unaccustomed to all the free space; coming home at rush hour the train is always SRO. Now I had it almost all to myself. On the other end of the car was a college girl drinking coffee, all spread out with books and bags and scarves. Midway between us were two blue-collar fellows with construction boots up on seats, talking too loudly about the Yankees. Aside from the bartender and me, that was it. The beer was crisp and tasted sweet. A calm feeling spread from my brain into my throat, down my chest, and all the way to my gut.

I was going to get home a little before two o’clock. Claire would be at a tennis lesson, then home to meet the school bus, only the kids wouldn’t be on it. I was going to pick them up as a surprise and take them for ice cream, then we’d go home and my son and I would throw a ball around and my daughter would play Taylor Swift songs on her iPod, and it would be just like a Saturday except it was Monday. As I drove myself home from the train I was thinking this was a great idea, one of the best days I could ever imagine.

I burst through my front door in a hurry; I didn’t want to be in a suit. I bounded up the stairs two at a time, headed to my closet to change. It was when I reached the top step that I first noticed something askew. Everything looked normal, but it didn’t sound normal. There was a noise coming from the opposite end of the hallway that sounded both familiar and completely out of place at the same time. I started down the hall, loosening my tie as I passed the kids’ bedrooms, both empty and quiet. The sound was coming from farther down the hall. There was only one more room on the floor, a guest suite where Claire’s parents stay when they come to visit; they like that it is remote enough within the house to offer a bit of privacy. I don’t know that I’d set foot in that room in a year. As I approached my heart began to slow down, even before there wasn’t any question what I was hearing; my heart figured it out before my ears did. There was a keyhole in the door. I knelt, shut one eye, and when I looked in my heart almost came to a dead stop. What I saw was consistent with what I thought I had heard: a man and woman from behind, naked. He was pulling on a pair of jeans with no underwear beneath, long brown hair in a ponytail; I didn’t recognize him. The woman I only saw for an instant, a flash of dark hair, before she disappeared from sight, headed toward the bathroom. I watched long enough to see the man sit on the edge of the bed, still facing away, putting on his shoes. I don’t know why I didn’t wait to see his face—of course I should have—or, more important, why I didn’t confront them both right then. But I didn’t. Watching him tie his shoelaces was already more than I could bear; I didn’t want to see any more. I just stood up, opened my other eye, and dusted off my pants in the place where I had knelt. My mind was completely blank. My hands were beginning to shake. And my life suddenly didn’t seem so perfect anymore.

MY FIRST THOUGHT WAS of the sheets.

I remember vividly the day we bought them. They’re Frette, which is very fancy, and Claire and I got into an argument, first over how expensive they were, then over the pronunciation. Is it “fret”? Or the Frenchified “freh-tay”? I still don’t know the answer. What I do know is the reaction I get from Claire if I approach the sheets while wearing shoes: it’s as though I’m walking toward the Mona Lisa with a pair of scissors. She treats the sheets the same way my mother used to treat the good towels when I was growing up. The better towels were always in the guest bathroom, even though we never had any guests; they were all at my father’s house. But that wasn’t the point. The point is: I might have just witnessed the finish of my wife having sex with another man, and my first thought was of the sheets. The mind is funny that way. Oftentimes, the first thought it has is one that doesn’t do you any good at all.

My next thought was that I was freezing. It was seventy degrees in the house but I was ice cold, shivering. There were so many things I could have done—should have done—but in that instant I didn’t think of any of them. All I could think was that I needed to get warm. So I turned around and went back the way I’d come, out into the sunshine. I didn’t look to see if Claire’s car was in the garage, or any other car for that matter. Instead I just stood in the driveway and watched the postal truck as it rambled toward my house, paused at my neighbor’s box, dropped off some mail, and rambled on. I don’t know my mailman’s name but he smiled and waved as he rambled toward my mailbox, opened it, dropped off my mail, and rambled on. I’m not sure if I waved back or not. On the lawn across the way, my neighbor’s yappy little Jack Russell terrier was racing about in circles. The circles weren’t consistent; sometimes the dog stopped and changed direction. I thought maybe it was chasing a butterfly. My neighbor’s wife came down her driveway, wearing workout apparel and a pleasant smile. “Hey, Jon!” She looked down at the dog and shook her head; she knows the dog is a pain in the ass. “You’re home early!”

“Yes,” I said, and watched as she went to her box and fetched her mail, then snapped at the dog to behave and went back inside. The dog paid no attention; it went right on running in circles. I heard the whirring and clicking of a sprinkler kicking on, maybe even mine, I’m not sure. Someone’s grass was being watered; it didn’t really matter whose.

I was thinking of the day my grandfather died, when I was twelve years old. We were at the hospital, my mother and I, and I remember standing on the sidewalk on a busy street in Manhattan when it was time to leave, staring in amazement at all of the normalcy that surrounded me. How could the garbagemen and the shoemaker and the meter maid and the honking truck driver all be going about their business as though nothing was at all unusual? Didn’t they know it was not a normal day? That’s what I was thinking about while my postman was delivering mail and my neighbor’s dog was chasing a butterfly and my wife and a stranger were getting dressed in my house.

I wasn’t cold anymore. I just needed to see the kids. I was feeling so far from normal, I desperately needed normalcy; I needed my kids. So, rather than waiting for whomever it was to leave my house—or, better yet, slamming through the door and demanding answers—I did probably the least sensible thing I might have under the circumstances: I got into my car and drove away. I backed slowly out of the driveway, watched the mail truck and the dog running in circles in my rearview mirror until they disappeared from sight, then turned left on the main road and drove toward town.

The silence in the car was soothing for an instant, then it became deafening. It left me nowhere to go but inside my own head, which just then was not the best place to be, so I turned on the satellite radio, set to the channel that plays eighties music. Howard Jones was singing “Things Can Only Get Better.” Down one notch to the seventies was “Don’t Pull Your Love.” I kept clicking around, trying to find a song that fit my mood, with no success. What I needed was a song that could turn time back ten minutes or so, and since no song can do that I finally just shut off the radio and drove to school.

I love visiting the school my children attend. I don’t get there often, which may be part of the reason I so enjoy it. I find I feel peaceful and at ease when I am in the building no matter how loud all the children are when the bell rings; even the chaos is therapeutic. It reminds me not at all of the strict, competitive environment in which I was raised. My father insisted I attend the most elite New York prep schools, just as he had, a demand my mother honored even though he went out of our life the day I turned nine. My kids’ school is nothing like that; it is a warm, nurturing place where the emphasis is on sharing and kindness. Claire occasionally voices concern that the school isn’t academic enough, but nothing could worry me less. There will be ample time for all of that—eventually their entire lives will be all of that. Right now they are in fourth and first grades; let them be kids.

When I pulled into the parking lot I was still more than twenty minutes early. Instinctively, I reached over to the passenger seat, where my iPhone would be in the zippered pocket of my briefcase, only there was no phone. There was also no pocket, and no briefcase. Which meant my credit cards, driver’s license, the New York Times sports section, a tube of Purell hand sanitizer, and a roll of Tums were all gone. I felt my face flush, a moment of panic; this was the last thing I needed. Visions of standing in line at the DMV flashed through my mind. But then, just as quickly, the answer came to me. The briefcase was not lost; in fact it had probably already been found. There was no question I was holding it when I went into the house, and equally little doubt that I wasn’t when I left. I was sure the briefcase was inside, I just wasn’t sure where. Though it didn’t much matter. If it was destined to be found then it would be. If Claire stumbled over it she would, no doubt, be surprised and confused, which would make two of us; I’d deal with the briefcase when I got home.

I got out of the car and walked over to the playground. A few small kids were running around, none that I recognized. One, a little blond boy with too-long hair, was on his tummy on the ground; I think he was licking the grass. I wanted to grab him by the belt—if he was wearing one—and lift him out of the mess. But before I could, I heard a familiar voice.

“Daddy!”

There is no other word that sounds like that one does. And it never sounded quite as good as it did right then, on that playground, the sun shining on my face.

It was Andrew, age six, racing toward me, one shoelace untied, breathless. “What are you doing here?”

“I came to see you, of course,” I said, and to my surprise my voice cracked.

I knelt and he ran into me, full speed, almost knocked me over backward. Phoebe was a few steps behind him, also running, though not quite as fast. Excited, though not quite as much. I wrapped my other arm around her and squeezed them both tight, buried my face in Phoe

be’s hair so I could smell her shampoo, like raspberries and a rainy day.

“What are we going to do?” Phoebe asked.

I cleared my throat. “Well, I had an idea,” I said, my voice returned. “How about if we see if the ice cream shop is open on Mondays?”

Phoebe threw her arms up in the air and cheered, while Andrew, less certain, wrinkled up his nose as he does when he is thinking especially hard. “I’m not sure,” he said. “I think I’ve only ever been there on weekends.”

“Let’s find out,” I said, and took them each by the hand and walked jauntily toward the car, feeling marginally better. That’s the thing about kids. They can’t make all right a thing that could never be all right, but they can make it as close as it can possibly be. That’s how I felt just then: as close to all right as I possibly could.

A few minutes later, after the short drive to the ice cream shop, during which Phoebe was ecstatic and Andrew was genuinely nervous that it wouldn’t be open on a Monday, I made a discovery of an entirely different sort: I couldn’t taste anything. I ordered soft-serve vanilla in a waffle cone with chocolate sprinkles and paid with the twenty bucks I keep in the ashtray for emergencies. On the first lick my thought was it didn’t taste right, and on the second I realized it didn’t taste like anything at all. This confused me because in every movie when a woman is wronged she turns to ice cream for consolation, and never once have I heard Sandra Bullock say: “You know, I can’t even taste this.” I tossed most of the cone in the trash. My son was delightedly licking chocolate from between his fingers; my daughter was wearing the contented smile of a nine-year-old who just got ice cream she wasn’t expecting. Then we all piled into the car to drive home. And I assumed my life was about to change forever.

SO MANY THINGS HAPPEN in my house when I’m at work. There are deliverymen with packages and lawn-care professionals with mowers and electric company inspectors with measuring gadgets and pool cleaners with long nets and Girl Scouts with cookies and religious nuts with pamphlets and the cable guy between noon and six and somebody’s mom with a jacket my daughter left at a birthday party. I have always been a bit intimidated by the sheer volume of activity Claire manages around the house, though I suppose I’ll never quite think about it the same way now.

I turned onto our street and saw Claire at the end of the driveway, poking through a magazine, the day’s mail tucked beneath her arm. She was looking the other way, in the direction the bus would be coming from any minute. I reached in the glove compartment for my glasses, which I ordinarily only use for driving at night. I wanted to see her face as clearly as I could when she turned and saw me coming. Would there be anything there? A tick? A shudder? A moment of panic? I put the glasses on and took a deep breath, then tapped gently on the horn.

Claire turned, squinted, and stared, shielding her eyes from the sunlight with her hand, looking appropriately surprised. As we approached her face broke into a wide smile, and she began waving goofily at the kids, who both unsnapped their seat belts and leaned into the front seat, shouting.

“Daddy came home early!”

“We had ice cream!”

“Hi,” I said, lowering my window. Claire walked right up alongside the car, looking perfectly normal. I hadn’t any idea what to think. “How was your day?” I asked.

“My day is still going on,” she said. “Is everything all right?”

Of course, that was the pertinent question. Is everything all right? I hadn’t any idea what the answer was. My sense was everything was probably as far from all right as it could ever be. But I wasn’t ready to say so. “I just missed everybody,” I said.

“Now, that is nice,” she said sweetly. And then, with enthusiasm, “Isn’t it nice to have Daddy home?”

“Oh yeah, oh yeah, ohyeahohyeahohyeah!”

“It’s lovely to have you home,” she said, and leaned closer to kiss me, but I pulled forward into the garage before she could.

“I’ll be back in a minute,” I said as the kids rushed for their scooters. “I’m going to run inside and change.”

I said that staring straight at Claire, certain there would be a signal of something in her face. Surely she would want to beat me inside, to straighten up, something. But there was nothing. She never diverted her gaze from the kids.

Alone, I went inside and up the stairs. For the second time that afternoon, I turned right instead of left, away from our bedroom and toward the guest room. The door was open, the French sheets in place, normal, crisp; they appeared clean. I couldn’t bring myself to smell them, but there was no indication there would be anything out of the ordinary to smell. It looked the way the room always looks, the sheets looked the way they always do, the family photos on the nightstand in place, the four of us staring at me, smiling.

I considered, for a moment, that I was losing my mind. I hadn’t experienced a hallucination since my sophomore year in college when I was talked into trying acid and spent three hours hiding under a blanket because I was absolutely certain the poster of Jimi Hendrix was breathing. I remember not knowing what to think back then, and now as I stared at a perfectly normal bed in a perfectly normal room, I didn’t know what to think again.

I had an hour before a car would arrive to take me to the airport, so I changed out of my suit and into jeans. I was on the stairs headed back down when I heard The Police singing “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic.” That’s the ringtone on my iPhone, which meant my phone was ringing and I could hear it. I looked downstairs toward where the music was coming from and saw my briefcase right in the center of the living room where I had dropped it an hour before. And, a few feet away, staring at it with a puzzled expression, was Claire. She didn’t see me on the stairs, just heard the music and saw the briefcase, and her head dropped to the side, the way a dog’s might when trying to make a decision. She had to be trying to decide why she hadn’t seen me carry in the briefcase, wondering how it had managed to get from my car to the living room. Maybe she was trying to decide if I had seen her, if I knew. She looked worried. Not enough that anyone else would have noticed, but I know her really well. I know when she is worried, even if it is only a little.

When she finally shook her head and walked away, backward, into the kitchen, I found myself thinking of Hawaii and the night I proposed to her, both of us tipsy, she especially because the seasickness medication she had taken made her susceptible to the champagne. There came a moment when both of us knew it was time, a momentary silence across a candlelit table when our eyes met and there wasn’t any question about it. Nor was there any question that I was the one obligated to begin, which I did, on my knee in a crowded restaurant. Twelve years later, alone at the top of the stairs, with the kids waiting outside, I decided this time it was Claire who was obligated to begin. Maybe she wouldn’t get on her knee, but she would tell me.

I ran down the stairs and outside, grabbed a basketball, and shouted for Andrew, who came scootering across the driveway, followed by his sister. We were on the court for almost an hour and I remember none of it; I couldn’t feel the joy of my children any more than I could taste the ice cream. All I could think of, through the yelling and the scootering and the slam-dunking, was my wife staring at the briefcase. Maybe she still was. Suddenly, without a word of explanation, I raced inside, leaving the two children alone. I needed to see if Claire was staring at the briefcase.

She wasn’t.

I found the case exactly where I had left it and Claire nowhere near it. Was she upstairs, furiously laundering expensive sheets? Or in the bathroom, cleansing herself of whatever residue remained after an afternoon tryst? Or perhaps she was hidden in the attic where no one would find her, silently crying tears of remorse.

Then I heard the clatter of pots and pans and realized she was none of those places. She was behind me in the kitchen, rustling about in the drawer where the cookware is kept. It was a startlingly normal place for her to be and a startlingly normal thing for her to be doing; the only thing out of place was the briefcase.

You see, I know my wife as well as I know anyone. I don’t claim to understand her, but I know her, which means while I cannot analyze most of the things she does, I can usually predict them. There is no way, under normal circumstances, she would ever leave my briefcase in the center of the living room floor. My wife is the sort who reminds you to put things away before you have even removed them from their place. If you say to her: “I think I’m going to watch a little television,” she will reply with: “Sounds good, make sure you leave the remote control where you found it.” She cannot, and does not, tolerate clutter. But now, she had made the conscious decision to leave my briefcase in the center of the floor where my children could trip over it or the dog could chew it up or a neighbor could see it and assume the household was in a state of abject chaos. That wasn’t normal.

This was my chance to let her know it was time. “Honey,” I shouted, as close to calmly as I was capable of. “Have you seen my briefcase?”

She was kneeling behind the island in the kitchen, still rummaging noisily among the pots and pans. Without looking up, she called back, “I think it’s in the living room!”

“What is it doing there?” I asked accusatorially.

Claire stood, popping from behind the island like a magician making an appearance after having been sawed in half. “Where are the kids?”

“Shit,” I said, and ran back out through the garage without another word.

If the children were surprised to have been left alone they didn’t indicate it; they had just continued singing and slam-dunking and scootering as though I’d never been gone. We stayed outside and played until the familiar black Town Car pulled into the driveway.

Phoebe put her hands over her nose and smiled. That’s her inside joke with me. The driver from the limousine service I use, Sonny, is dependable and friendly but has a bit of an odor problem. It doesn’t bother me as much as it does Claire; the kids think it is absolutely hilarious.

What his arrival meant was that it was time for me to leave for the airport, so I took the kids inside for cold drinks. When we got to the kitchen, Claire was in front of the stove, warming olive oil in a pan.

“Wash your hands!” she yelled, adding, just for me, “That includes you.”

I did. Then I got a bottle of water and two juice boxes from the refrigerator. And then, as casually as I could, I wandered into the living room without a word and saw that my briefcase was no longer on the floor.

WHEN I BOARDED THE jet I found Bruce stretched on the couch, watching basketball on an iPad, a silver tray of chocolate chip cookies balanced on his stomach. Bruce is a brawny man with voracious appetites, not limited to food, though he does eat as much as anyone I have ever seen. Since we began traveling together I have observed, with a combination of awe and disgust, that there is never a time when food is placed before him that he will not eat, and there is nothing discerning about his palate; from French truffles to Buffalo wings, Bruce will always partake. And, amazingly for a man of fifty-one, he pays no noticeable price.

There was a smile in my voice as I slid into the seat beside him and motioned toward the cookies. “You going to save any of those for me?”

“Have,” Bruce said without looking up from the game. “There’s plenty.”

I shook my head. “You know the story of Dorian Gray? Somewhere in the world there is a painting of you as a very fat man.”

Bruce still didn’t look up. He is not the sort who cares if you give him a hard time. I can tell you a great many things about my CEO, some of them not so attractive, but the one thing I will always credit him with is supreme self-confidence. I have never seen Bruce express a shred of doubt in himself, his leadership, his athleticism, anything. He will eat and drink and buy whatever he wants, fight or fire or fuck whomever he wants, and never look back. He is like a shark in that way, more machine than beast, because of the singularity of his focus. He considers nothing and no one that interferes with his intentions and it’s hard to argue with the results: Bruce is among the most powerful executives on Wall Street, has unwavering support from his board of directors, and has to be worth close to a billion dollars. He also has a beautiful, doting wife who tolerates all of his indulgences, including the rampant infidelity of which she could not possibly be unaware.

“Who’s playing?” I asked.

“Lakers,” he said, still not looking up. Bruce consumes sports as voraciously as he does food, and wagers huge amounts on basketball and football.

I was trying to act normal. I wasn’t feeling normal, but I was trying to behave as though all was well because I didn’t want Bruce to notice. He is very hard to lie to, and I really didn’t want to tell him I was pretty sure I had found my wife with another man.

I took out my iPhone and fiddled with it. “We waiting for anyone?” I asked.

“Just you,” he said. “Should be wheels up in a few minutes. You want to watch this?”

“No, thanks,” I said. “I need to respond to a few things.”

The screensaver on my phone is a picture of Claire and the kids and me at Disney World. We had stopped at a stand where they painted faces and Phoebe wanted hers done but Drew, then only four, was afraid and would only do it if we all did. So in the photo my daughter has butterfly wings extending from her eyes, my son is Bozo the Clown, I have a tiger’s stripes and fangs, and Claire is a fairy princess. It is the only picture I have on my phone; Phoebe e-mailed it to me and then made it my background. It always puts a smile on my face. Even now.

I opened a new e-mail and entered Claire’s address. In the “subject” field I entered: This afternoon. Then I rolled the device about in my fingers, glanced over at Bruce, picked one of the cookies off the tray, and popped the whole thing in my mouth.

“Something to drink, Mr. Sweetwater?”

I had forgotten all about Sandra, our flight attendant, a delightful woman of about sixty, always cheery and deathly afraid of flying. She applied for the job when Bruce first bought the plane and he was taken by her sunny disposition and professional manner; it was not until the first time they hit a patch of turbulent air that her fatal flaw was revealed. I usually give Sandra a hug upon boarding but I wasn’t myself this day.

“Would you like a drink?” she asked again sweetly.

I pointed apologetically to my mouth as I chewed the cookie.

“Perhaps a glass of milk?” she asked.

I swallowed. “Just some water,” I said, rising, “and I’m sorry I didn’t say hello—how are you?”

She gave me a quick hug, then pointed at the iPhone and shook her head. “Always too busy with that thing. You tell the boss here not to work you so hard.”

I still hadn’t quite decided what I wanted to say to Claire when I heard the engines roar to life. I sipped from the near-frozen bottle Sandra had brought and wiped my hand on my pants. My mind was racing and yet I was perfectly still. I could hear the roar of the engines, the reverberation of the fuselage. Sandra was taking her seat, strapping herself in, pulling her lap belt impossibly tight, crossing herself. I felt so empty it was like someone had sliced me open, removed all my organs, and sewed me back up again. There was nothing left inside.

I covered the screen of my iPhone with my left hand as I typed with my right, even though no one was around to see, nor would anyone, even Bruce, read over my shoulder. But there are some things you just don’t take chances with, even if the chances are zero. I didn’t want anyone to see the words I was typing. I didn’t even want to see them myself.

I came home early. I saw you.

One of the two pilots, a pleasant, round-faced fellow whose name I never remember, stepped out of the cockpit. “We’re ready to go, gentlemen,” he said.

I nudged Bruce, who looked up from his game for the first time since I’d boarded. I pointed a thumb up in the air, and he nodded and shut down his iPad. Then he glanced up at the pilot and put his own thumb in the air.

The pilot disappeared again and I leaned back in my seat, closed my eyes. Bruce might want to chat now and I wasn’t ready. Once we were in the air he could activate the satellite and watch the game on the television embedded in the front console; that would be just a few minutes. We were taxiing, my thumb hovering over the icon marked send. My eyes were closed, the engines roared in my ears, a faint aroma of jet fuel wafted through the cabin, and my head began to spin into what felt like a dream but was actually a memory. I was remembering the best night of my life.

Claire and I were on a beanbag in front of a fireplace, miles away, years before. A fire was crackling and the heat warmed my face, in the wonderful way that only follows a day of skiing in bone-chilling cold. We were in the Poconos, in Claire’s parents’ home, the night before Christmas. Three days later we would travel to Hawaii to celebrate New Year’s. Five days later I would ask her to marry me. But that night, on that beanbag, drinking warm apple cider laced with rum, our feet digging into a white shag rug, Claire was talking about the two kinds of people in the world.

“There are those you lie to and those you lie with. At the end of the day, that’s the most important distinction you can make. When you concoct a lie, am I in it with you? Or is it me you’re lying to? If you promise always to lie with me and never to lie to me, I’ll do the same.”

Her face was so close to mine our noses touched, and I could smell the apples and cinnamon on her lips, feel the warmth of her breath. It was the closest I have ever been to anyone, in every way. It didn’t feel like lightning at all—just the opposite. Lightning is loud and scary; Claire made me feel quiet and safe.

I took her hand in mine and held it to my face, kissed the tips of her fingers. They were chilled despite the heat of the fire. I put them to my cheek and pressed them against my skin. I wanted to promise her so many things. I wanted to tell her that I knew, from the first moment we met, that I needed to be with her, in the same way that I knew I needed to breathe to stay alive. I wanted to tell her that she made me feel as though I had spent my whole life looking in all the wrong places for all the wrong things, because it was clear to me now that so long as I could smell her breath and feel her frozen fingers on my face, then everything was all right and always would be. I wanted to tell her that all I needed in the world was for her to marry me. I would have proposed to her right there on that beanbag in front of that fire, but just then her mother walked in.

“My, look at you two,” she said. “I can hardly tell where one of you ends and the other begins.” She said it in a sweet way, as though she could feel at least part of what I felt. But if she had any inkling of what she was interrupting she didn’t show it. She just dropped onto the sofa and breathed a heavy, exhausted sigh.

“He’s a handsome one, isn’t he, Mom?” Claire asked.

Her mother chuckled softly. “Oh, I’d say everything is about where it’s supposed to be.”

Claire was looking into my eyes as she spoke. “He’s a sweet one too, isn’t he?”

“He is,” her mother replied. “But it’s the sweet ones you have to watch out for, because they can get away with murder and they know it.”

“Can you get away with murder?” Claire asked me.

“Probably,” I said, “but I promise I will never try.”

We both knew what I meant. Claire’s smile was the softest I had ever seen. It said she was as comfortable as I was, that she knew everything I wanted to say. Not just then, but always. The way Claire looked at me said she knew better than I did what I felt and what I wanted, and that she had always known. Her face could say that to me back then. Sometimes it still does.

I would have asked her to marry me right there had her mother not fallen asleep on the sofa. Instead, it was five days later that we became engaged, but to this day I better recall the way I felt that night, by the fire, than I do when I knelt before her a few nights later. And I’ve always felt as though the promise we made to each other that night, to always lie together and never apart, was the most significant we ever made. It’s a promise I’ve thought of often and never broken, not a single time in all these years. And I was always certain she hadn’t either. Until today, when suddenly I wasn’t certain of anything at all.

Then I heard the sounds of a basketball game on television, and I opened my eyes and found the game on the flat-screen. Bruce was again stretched out on the couch, a contented smile on his face, the silver tray of cookies balanced precariously on his stomach. I hadn’t even realized we’d taken off, but as I looked out the window the lights below seemed a lifetime away. I looked over at Sandra, who was seated with her eyes tightly shut, mouthing what was surely a silent prayer.

I looked back to Bruce. “How long was I asleep?” I asked.

His eyes never left the screen. “Fifteen minutes. Maybe twenty.”

I nodded. The iPhone was still in my hand. I entered my passcode and rubbed a finger over the face, clearing away a smudge from the screen. The words were crystal clear and seemed unusually bright.

I came home early. I saw you.

“No,” I said aloud, though Sandra couldn’t hear me and Bruce wasn’t listening. “I’m not ready for that.”

I hit the delete button and the words disappeared, instantly replaced by the Disney World picture again. There we were, the four of us, in face paint. We looked so happy, like the perfect family, an advertisement for Disney World. I stared at the picture as we ascended through the clouds, and quietly thought that I would have traded anything in the world just then to have been one of us.

WHEN WE LANDED IN San Francisco I was exhausted and Bruce was starving. Only one of those was unusual; I am almost never exhausted. Bruce is almost always starving, and one of the few drawbacks of traveling with the CEO is that when he is starving you eat, even if it is after midnight where you woke up that morning, back in the life you had before the afternoon changed everything.

We ate in the restaurant at the hotel, four-star French cuisine with a wine list roughly as long as the Old Testament. We were seated immediately, at a private table in the rear, and Bruce ordered Belvedere on the rocks and a Coca-Cola.

“I’ll have the same,” I told the waitress, “but hold the Coca-Cola.”

Bruce smiled. He doesn’t like to drink alone.

“You win?” I asked.

He knew I meant his wager on the Lakers game. “Won big.”

I nodded as the waitress brought the drinks. “I’ll drink to winning big.”

Bruce clinked my glass with his, then looked up to the server. “Skip the Coke,” he said, “and keep these coming.”

Two hours later we had finished two sirloin steaks, baked potatoes, creamed spinach, a loaf of freshly baked bread, salads with Thousand Island dressing and a bottle of four-hundred-dollar Bordeaux. Bruce was leaning back, swirling the last of his wine in the glass. “This is where I really miss cigars,” he said.

“You’ll live longer,” I said.

“I think I’d rather live shorter and smoke a cigar every now and again,” Bruce said, a faraway look in his eyes. “They make me think of Brooklyn. My father loved cigars. Every night after dinner he would have a glass of brandy, and he would smoke a cigar and dip the tip of it into the brandy while he smoked.” Bruce poked his finger into the glass. “He said it added flavor to the wrapper. My father was always working and he was always stressed out; he hated being poor and could never do anything about it. The only time I ever remember him relaxing was after dinner; he’d smoke his cigar and we’d talk about baseball.”

“Which team? The Yankees?”

Bruce looked at me with horror. “My old man hated the Yankees. They were the enemy. My father’s team was the Dodgers, the Brooooooklyn Dodgers.”

“You aren’t old enough to have seen the Dodgers in Brooklyn.”

“No, I’m not,” he said, still sloshing his glass. “But he was. He never got over them leaving Brooklyn. My mother used to say he started dying the day they left. Which would mean he started dying the year I was born.” He paused, sucked the wine off his forefinger. “After the Dodgers left my father didn’t have a team to root for, so after dinner we talked about how badly he wanted the Yankees to lose. He became obsessed with them losing. He didn’t care who won, so long as the Yankees lost. If you asked which was his favorite team, my old man would say it was whoever was playing against the Yankees.”

“At least you still had the time together,” I said.

Bruce stared right in my eyes. “When you root for a team, you celebrate when they win,” he said. “When all you do is root against one, there is only misery. My father took no satisfaction in seeing the Yankees lose. He said he did but he didn’t, really. And he suffered when they won. There’s nothing in the world worse than rooting for something not to happen, because if that’s all you care about then all you can do is lose.”

Bruce leaned back in his seat, still sloshing the wine in his glass.

He was looking away, out a window. “That’s why I have never allowed myself to get attached to any team in my life,” he said. “I love sports so I bet on every game to keep it interesting. But as far as emotionally, I couldn’t care less.”

I felt a familiar flutter in my stomach. Fathers are complicated for me. “And you got that from your dad?”

Bruce turned back. “Johnny, we get everything from our fathers.”

I cringed. “Not me, unfortunately.”

“Even you. Even if you didn’t know him at all, you’re still his son. Whether you realize it or not, you are just like him.”

I shook my head vehemently. “No,” I said. “In my case, I’m not.”

“You are,” Bruce said. “Listen, the one thing I remember most about my old man is how much he hated being poor. He used to say to me all the time, ‘Brucey, we don’t have a pot to piss in.’ That was his big phrase: A pot to piss in. All I wanted was to get rich and get him the hell out of Brooklyn. I didn’t make it. He died two years before I got to high school. But even after all that time, when I bought my mother her house on Long Island, I told the designer I wanted the word ‘pot’ engraved in gold on every toilet.” He started to laugh. “He thought I was crazy.”

“You bought your mother a pot to piss in.”

“That’s right,” he said. “Because we are always our fathers’ sons, whether we like it or not.”

Bruce got quiet then, just finished the rest of his wine, and we called it a night. We had an early start in the morning and a long day ahead. I went upstairs, undressed, and then lay in the unfamiliar darkness of the hotel room, exhausted but unable to sleep. And what I found was that I was thinking more about my father than I was my wife.

THIS SEEMS AS GOOD a time as any to mention that my name is Jonathan Sweetwater, and yes, he was my father. Percival Sweetwater III.

Five-term United States senator, liberal lion, legendary lothario and bon vivant, author of nineteen books, sponsor of eleven legislative bills, trusted adviser to three presidents, husband to six women, and father to one boy.

That’s me.

You are likely asking the same question I never got to ask him, which is: If he was Percival the third, why wasn’t I Percival the fourth? I didn’t ask him because I never saw him again after my ninth birthday party. But, fortunately or not, he was asked the question by his chosen biographer.

“I didn’t name my son Percy,” he was quoted as saying, “because, let’s face it, there could never be another one like me.” It wasn’t made clear in the book if he was kidding, or even smiling, when he said it. Knowing what I do of him I’d say it’s likely he was not.

I was born when my father was in his forties and still on his first wife, my mother, Alice, of whom he told the press on their wedding day: “She puts the ‘sweet’ in Sweetwater.” It was a line he would use five more times, with each of his subsequent wives, and with no hint of apology. When reminded by reporters that it wasn’t the first time he had used the phrase, his stock response was: “In life, as in Congress, we rarely get things right the first time.” With women, Percy continued trying to get it right throughout his life. When it came to children it seems he gave up after me.

On the rare occasion that a reporter contacted me I too had a stock reply, which never failed to generate a laugh. “Mother’s Day,” I would say, “has always been my most expensive day of the year.” It was funny, but it wasn’t true. Of my father’s six wives, I only ever met two. And apart from my mother, I haven’t been in touch with any of them in thirty years. But that doesn’t make the line any less funny. I learned that trick from my father too: another of his stock comments was “Percy Sweetwater never lets the facts get in the way of a good story.”

How, you may wonder, did a man so brazenly self-indulgent manage to ascend to such a towering place in society? The best answer I ever got to that question came from my mother, who had more reason than anyone to bad-mouth Percy but never did. “Say what you will about your father,” she told me, “but at least he was his own man. He was unapologetically, unequivocally, unreservedly himself. And in the world we live in today, people respond to that.” I always thought she might have been talking more about herself responding to Percy than anyone else, but either way it remained that Percival Sweetwater III was a treasured figure in American politics.

When my father died, the New York Times eulogized him as THE LAST LION. The funeral was covered by CNN, MSNBC, and all the major broadcast networks; I saw the satellite trucks parked outside the church on Fifth Avenue. In fact, they were all I saw. I didn’t get into my father’s funeral. I was invited, but I managed to misplace the invitation somewhere en route from my apartment, a mistake my mother called “the ultimate Freudian slip.” I tried to explain to the security guards outside the church doors that I was the son of the deceased, but it was very much like trying to talk your way past the bouncers guarding the velvet rope at a nightclub: they were listening to me, but they couldn’t have cared less what I was saying.

I watched from across the street as two former U.S. presidents entered the church. Then I went into an Irish pub, ordered corned beef and cabbage, washed it down with four beers, and watched the coverage on television. Then I went into the men’s room, threw it all up, rinsed my mouth and face with cold water, and went to the office.

When I told my mother what happened she responded by giving me a gift. It was a car, with vanity license plates. not iv. She said that was the perfect sentiment for me to express to the world as I passed it by. It wasn’t especially funny but I laughed anyway. That’s the way it works when you have a famous father to drive away from: you make jokes even though there really isn’t anything funny at all.

My Father's Wives

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0062325876

- ISBN-13: 9780062325877