Excerpt

Excerpt

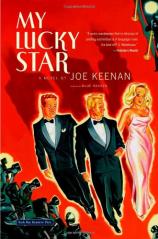

My Lucky Star

It is never a happy moment in the life of a struggling artist when some fresh assault on his fragile dignity compels him finally and painfully to concede that Failure has lost its charm. He has up until this point soldiered bravely along, managing to persuade himself that there’s something not merely noble but downright jolly about Struggle, about demeaning temp jobs, day-old baked goods, and pitchers of beer nursed like dying pets into the night. He would, of course, grant that la vie Bohème with its myriad deprivations and anxieties was not an unalloyed delight. But whenever its indignities rankled unduly he could console himself with his certainty that Bohemia was not, after all, his permanent address. Oh, no. His present charmingly scruffy existence was a mere preamble to his real life, a larval stage from which he would soon gloriously emerge into the sunshine of success. Its small embarrassments were, if anything, to be prized, not only for their lessons in humility but for the many droll, self-deprecatory anecdotes they would later provide, stories he’d polish and trot out for parties, interviews, and—why be pessimistic?—talk shows.

Then one day he is faced with some final affront, minor perhaps, but so symbolically freighted as to land on him with the force of an inadequately cabled Steinway. He reels, stunned, and dark speculations, long and successfully repressed, rampage through his mind. For the first time he allows himself to wonder if his life twenty years hence will be any different than his present existence. “Of course it will be different,” coos the voice in his head. “You’ll be old.”

From this icy thought a short road leads to panic, and from panic to despair, self-pity, desperation, and, finally, Los Angeles.

MY OWN RUDE EPIPHANY came a year ago last fall shortly after the closing of Three to Tango, a larky little comedy I’d written with my good friend and collaborator Claire Simmons. The play had been enthusiastically received in a series of readings, stirring a cautious hope in Claire’s heart and extravagant optimism in my own. The production, alas, was doomed from the start, owing chiefly to our producer’s decision to present the show in a small basement playhouse that was as damp as Atlantis and harder to find. We tried to persuade him that the show might fare better in a space that felt more like a theater and less like a hideout, but he felt confident that people would find us. People did not. We opened in mid-September and by month’s end the play had closed and I was back to my day job, pounding the pavement as an outdoor messenger for the Jackrabbit Courier Service.

You might suppose this experience would have left me a broken and bitter man, but on the day in question my mood was actually pretty chipper. The autumn weather was brisk and lovely. The job, though lacking a certain prestige, allowed me to write much of the day, and I’d just gotten an idea for a new comedy. Best of all, my chum Gilbert, whose consoling presence I’d sorely missed during the deathwatch for my play, was due to return soon from Los Angeles. I’d been slightly miffed at his desertion but couldn’t really blame him. His mother, Maddie, had recently snagged herself a rich Hollywood mogul, and Gilbert—who if mooching were an Olympic sport would have his picture on Wheaties boxes—could not resist flying west to bond with the lovebirds poolside. I looked forward to hearing of his romantic exploits, which, if the hints in his e-mails were any indication, would give new life to the phrase “Westward Ho.” So buoyant in fact was my mood that I was even coping stoically with the news that a musical penned by the loathsome Marlowe Heppenstall, my nemesis since high school, had opened to unfathomably kind reviews and was looking like a major hit.

By late afternoon the benevolent sunshine had given way to darker skies and a sudden cloudburst forced me to sprint the six blocks to my final destination, a Park Avenue law office. I raced into the building, ascended to the seventeenth floor, and entered a spacious foyer, every mahogany-paneled inch of which bespoke the age and prosperity of the firm. The prim, bespectacled woman at the desk glanced up and fixed me with that look of quizzical disdain legal receptionists have long reserved for dampened members of the messenger class.

I removed from my satchel an envelope addressed to a Mr. Charles O’Donnell and marked PERSONAL. I presented this to the human pince-nez, who gazed right past me and said, “Mr. O’Donnell, this just came for you.”

I turned. Walking toward us was an extremely handsome blond fellow about my age, dressed in a flawlessly tailored charcoal pinstriped suit. He had wonderfully broad shoulders though I couldn’t say if this was the result of weight training or if it was workout enough just lifting the massive Rolex and chunky gold cuff links that sparkled on his tanned wrists.

Reminding myself, as I need to at such moments, that this was not a movie and the fellow could see me, I tried not to stare too blatantly as I handed him the envelope. He took it, barely glancing at me, then did a little double take as though he recognized me but wasn’t sure where from. He suddenly looked familiar to me as well. I wondered if we’d shared some fleeting romantic liaison but immediately dismissed this notion as it hinged on the ludicrous premise that I could have slept with such a man then forgotten him. I knew that if we’d dallied even once ten years ago, I’d still be mooning over him and writing maudlin sonnets starting “If love, thou wouldst but phone me once again.”

His puzzled look morphed suddenly into a smile of delighted surprise.

“Phil?” he said. “Phil Cavanaugh?”

Light dawned.

“Oh my God! Chuck O’Donnell! How the hell are you?”

“I don’t believe this. It’s so great to see you!”

We’d been friends back in high school, though only briefly as we’d moved in very different circles. Chuck had been the brightest member of the football-playing, cheerleader-groping set, while I had been a leading light of the sarcastic, underwear-ad-ogling theater crowd. He’d crossed lines once, gamely agreeing to play the braggart warrior Miles Gloriosus in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum when our own group failed to produce a single nonrisible candidate for the role.

I scrutinized his face, which seemed different, improved in some way.

“You’re looking at my nose, right?” he said with a laugh. “I broke it boxing a few times. They kept having to reset it.”

“Ah,” I said, wondering what it must be like to live so charmed a life that facial injuries only made you handsomer.

“Look at you.” I grinned. “Mr. Big Shot Lawyer.”

“Not so big, trust me. How ’bout you? Still writing plays?”

“Just did one.”

“That’s great! How’d it go?”

“Really well,” I said. “Big hit.”

It was the sort of fib I might have gotten away with had we met at a cocktail party and I was wearing the secondhand yet stylish jacket Gilbert calls my Salvation Armani. The problem was we weren’t at a cocktail party. We were in the stately foyer of his white-shoe law firm and I was wearing faded jeans, waterlogged Nikes, and a gray polo shirt adorned with my company’s logo, a zealous, bucktoothed rabbit in a mauve tracksuit. In short, I was in no position to swank.

Charlie, bless him, managed to say “Great” without a trace of irony, but the receptionist, who’d never liked me, didn’t even try to keep her eyebrows in neutral. Mortified, I averted my gaze, which landed on the foyer’s large gilt mirror.

I spoke earlier of moments that carry a great symbolic weight. This was unquestionably such a moment. There we stood, Charlie looking straight out of a Barneys catalog and I in my soggy ensemble from the Grapes of Wrath Collection. So perfectly did we exemplify our divergent fortunes that we might have been allegorical figures from some medieval morality play, with Charlie starring as Diligence Rewarded and self in the cameo role of Dashed Hopes.

“So,” said Charlie as the blood drained from my face, “been in New York long?”

“Since school,” I mumbled, searching for a way to say that, while I was enjoying our chat, I should really get going as I’d be needing to burst into tears soon. The receptionist, more eager to rescue Charlie than me, reminded him of an impending meeting.

“Gotta run. But hey, let me know next time you’ve got a show on.”

“You bet.”

“My wife loves the theater. In fact that’s what you just brought me—tickets for this new musical. Friend of mine couldn’t use ’em.”

“Ah.”

“Maybe you’ve heard of it?” he said, then smacked his forehead comically. “What am I saying? Of course you have. It’s by Marlowe—you know, Marlowe Heppenstall from school? Are you two still in touch?”

WHEN SUCH MOMENTS BEFALL US, we have, of course, two options. We can say “Fiddle-dee-dee” and shrug it off or we can surrender entirely to self-lacerating despair. I chose the latter course and, after walking sixty blocks in the rain to my small, unkempt apartment, settled into a chair with a nice view of the air shaft to contemplate my future.

It did not look bright.

I was twenty-nine. This meant I was still technically a young man, though no longer young young, thirty being, as everyone under it knows, the middle age of youth. True middle age was still reasonably distant, though not, as it had once been, unimaginably so.

My career to date had consisted of a frustrating series of near misses. While I’d never had any trouble imagining the ultimate breakthrough, it was now equally easy to picture this dispiriting pattern repeating itself till I woke one day to find I’d become that most poignant figure the theater has to offer, the Struggling Old Playwright.

I’d met my share of them, bloated pasty fellows, doggedly upbeat or surly and embittered, haunting the workshops and readings where their younger brethren gathered. I’d seen them in theater-district bars, cadging drinks while boasting of their latest effort, often a retooling of some earlier work culled from the trunk and reread with a parent’s myopic affection.

“Amazing how well it holds up! Why it’s more timely now than when I wrote it. Can’t believe Playwrights passed on it back then. Just as well though since Streep was too young at the time to play Fiona and she’d be perfect now. Damn, left my wallet home.”

There was one especially Falstaffian old gasbag whom Gilbert and I had often observed in our favorite watering hole. Not knowing his name, we’d christened him Milo. In my imagination, which had grown uncontrollably morbid, I pictured him twenty years from now, older, fatter, but still warming the same bar stool. I watched him turn toward the bar’s entrance, his blubbery lips parting in a smile of welcome. He patted the stool next to his with a nicotine-stained hand and bid the weary newcomer welcome.

“Philip! We’ve been wondering where you were. Wouldn’t be a proper Friday without you. Sorry I missed your birthday bash at the Ground Round. Any word from MTC on the new one? . . . The philistines! . . . How awkwardly you’re holding your glass—the old carpal tunnel acting up again? Well then, here’s a bug I’ll just put in your ear—you tell Blue Cross they can stuff their job, then come join me behind the necktie counter at Saks! What fun we’ll have, discussing our plays and ogling the young ones! I tell you, Philip, the days just fly by!”

This ghastly reverie was mercifully interrupted by the shrill buzz of my intercom. I shambled to the door and asked who it was.

“It’s me,” said Claire through the crackle of static. “Can I come up?”

I buzzed her in, relieved to have a sympathetic listener to whom I could relate the day’s tragic events. You can imagine my chagrin then when she burst melodramatically through the door, her mood apparently even fouler than my own.

“It’s over!” she declared hotly, stabbing her umbrella into the orange crate that served as a stand.

“Oh?”

“I mean it this time. He saw her again!”

“He,” I knew, referred to her boyfriend, Marco, a very hirsute ceramist Gilbert and I had nicknamed “Hairy Potter.” “Her” could have referred to either of his two former girlfriends. Since moving in with Claire he’d vowed to put them both behind him, though when he met one he tended to put her beneath him. Claire did not elaborate. She just removed her raincoat and hurled herself onto my couch, where she sat, arms crossed, awaiting compassion.

I found this quite irksome. I’d assumed that if there was any sympathy to be offered I’d be on the receiving end. To be asked, in my shattered state, to start dishing it out made me feel like a stabbing victim who’s just lurched into the emergency room, only to be tossed a pair of scrubs and told to get to work on the burn victims.

“What’s with you?” she asked, noting my tetchy expression.

“Sorry. It so happens I’ve had a pretty vile day myself.”

“Oh?” she asked.

There was a note of challenge in her voice, and, hearing it, I decided not to elaborate. A woman whose man has just done her dirty was not likely to care that I’d been seen to bad advantage by an old classmate. I could, of course, have thrown in the stuff about Milo and the necktie counter, but Claire’s a logical girl and would only have pointed out that my undistinguished midlife, however sad, was still somewhat theoretical, that her own misfortune had actually happened and that this was, perhaps, a useful distinction.

“Never mind. Scotch?”

“Please.”

I poured us both stiff shots of Teachers as Claire poured out her tale, which differed little from the others I’d heard since Marco had oiled his way into her heart. Three suspicious hang ups, questions as to recent whereabouts, inept lying, expert grilling, confession, tears, shouting, “Go back to your whore,” curtain.

“It’s really over this time,” she proclaimed. “I mean it.”

“Good.”

“And don’t roll your eyes.”

“When did I roll my eyes?”

“Just now. Inwardly. You’re enjoying this.”

“Excuse me?”

“You never liked Marco. You’re thrilled to see your low opinion’s been borne out.”

“Thanks a lot!” I said, miffed. “You think it pleases me when Chewbacca mistreats you? You’re my friend, for Christ’s sake. This upsets me.”

A noble sentiment, if not entirely true. There is, I confess, a small mingy part of me that feels, if not quite pleased, not exactly crushed either that, when it comes to men, Claire’s instincts are even sorrier than my own. It’s not that I wish her ill. It’s just that in every other aspect of our lives she’s so annoyingly and unquestionably my superior.

She’s smarter than me. She speaks four languages to my one and I’ve stopped even trying to play chess with her, as my odds of winning are the same I’d enjoy in a Czechoslovakian spelling bee. She’s a much better person too. She volunteers, writes thank-you notes, and adheres to a code of ethics the average bishop might find uncomfortably lacking in wiggle room. Most unforgivably, she’s more talented than me. She composes marvelous music, something I can’t do at all, and, when we write plays, tosses off bons mots and plot twists with a facility that leaves me feeling both dazzled and superfluous.

So when she periodically announces that she has, owing to her woeful misjudgment, taken yet another one on the chin from Cupid, my compassion is always leavened by an agreeable dollop of condescension. How nice for a change to be the one who gets to cluck sympathetically while thinking, “Poor dear, when will she learn?”

I topped off her glass and let her vent some more. When she’d finished I described my mortifying encounter with Charlie, adding several poignant embellishments.

“How awful for you!” she gasped. “There were actual pigeon droppings on your cap?”

“I had no idea till Charlie pointed it out!”

“How utterly tactless! Almost as bad as Marco. You know what he said when he left?”

“We’re on to me now.”

“Sorry, go on.”

When I’d finished we agreed that our souls required the healing balm that could only be provided by a highly fattening meal sluiced down with a suitably excessive quantity of wine. We were donning our coats, debating the relative merits of Carmine’s fettuccine Alfredo and Szechuan West’s Double-Fried Chicken Happiness, when my phone rang. I let the machine answer and heard Gilbert’s voice bellowing cheerfully from the speaker.

“Hi, Philip, it’s me! Are you there? Pick up! That’s an order! You may not screen this call!”

Claire shot me a pleading look, but I raised two fingers promising brevity and crossed to the phone as Gilbert continued his wheedling.

“Pick up! I have news, Philip! Amazing news!”

“Hey,” I said, “are you back early?”

“No, I’m still in LA.”

“When are you coming back?”

“Never!” he said exultantly. “I never want to leave this magical place and neither will you once you’re out here.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked, confused. “What’s this earth-shattering news?”

“He saw Cher at Home Depot,” said Claire.

“Tell Claire I heard that. What’s she doing there? No date tonight with Hairy Potter?”

“No, they broke up.”

“Do you mind?” said Claire.

“About time,” said Gilbert. “The hair on those shoulders! Like epaulets!”

“Your news?” I prompted.

“I got us a job!”

So intrigued was I by the last and loveliest word of this sentence, i.e., “job,” that it took me a moment to register the more ominous one lurking dead center. How could he have gotten “us” a job when there did not, for ample reason, exist any professional entity that could be described this way?

“What do you mean, ‘us’?”

“You and me, naturally. Claire too, of course. Can’t have her back home mooning over wolf boy while we’re off conquering Tinseltown.”

“The job’s for all three of us?”

“Hang up,” said Claire, her instinct for self-preservation undulled by the scotch.

“Yes. And for big bucks too. I should think at least fifty apiece.”

“Fifty thousand each?!” I exclaimed and even Claire’s eyes betrayed a wary glimmer of interest. “What is it, a writing job?”

“No, I got us a gig as astronauts. Of course it’s a writing job. We’re adapting a novel into a screenplay.”

“But . . . but how?” I sputtered.

“Connections, baby! I’ll explain it all when I see you tomorrow. You’re booked on the two-thirty flight. American Airlines.”

“Tomorrow?!”

“First class, of course!” he assured me, as if that were the issue.

“Tomorrow?”

“Is that a problem?” he asked impatiently.

“Well, it’s pretty damned sudden! We’re supposed to just drop everything and hop on a plane?”

“What the hell’s stopping you?” he said, getting testy.

“Well,” I sniffed, “I do have a job.”

The moment I said it I realized that, while there may have been valid reasons for me to reject such an offer, my standing commitment to trudge through Manhattan delivering parcels to the contemptuous was not the most compelling I might have offered. Gilbert concurred.

“Your JOB?” he shouted incredulously. “Your MESSENGER JOB? Are you insane?! For ten years I have listened and pretty damned patiently while you’ve bitched and moaned about your tragic career. Poor noble Philip, struggling to keep the torch of Molière aloft and no one will give him a break! Now I’m standing here handing you Success on a silver tray with tartar sauce and you’re arguing with me? I’ll only say this once—TAKE THE DAMN JOB! Pass it up and, as God is my witness, I’ll write the damn script myself, win an Oscar for it, then spend the rest of my life following you with a sharp knife and a saltshaker!!”

“All right! Calm down! Did I say we wouldn’t come? I just need to talk it over with Claire.”

“Talk all you like, just get her out here. And by the way, you’re welcome!”

“Give me a break, okay? This is all a bit abrupt.”

“That’s how things happen out here,” he said, all cheery again. “It’s a very impulsive town. I’m fitting in beautifully. See you at LAX!”

“Don’t hang up!”

“I’m late for a date. Your tickets will be at the counter. Bobby arranged it.”

“Bobby who?” I asked, but he was gone. I replaced the receiver and turned to Claire, whose face had taken on that stern squinty look it gets whenever Gilbert descends on our playground proffering candy.

“Well! How’s that for good news? He’s found us a job!”

“I gathered.”

“Hollywood, baby!” I said in my best Sgt. Bilko voice. “Our ship has come in!”

“Have you counted the lifeboats?” she replied and exited to the hall.

I locked the door and caught up with her in my building’s cramped vestibule-cum-gentleman’s lounge. She sailed grimly into the drizzly night and I fell in beside her, wondering how on earth I could coax her onto that plane.

YOU MIGHT SUPPOSE THAT a high-paying Hollywood job would not be a difficult thing to sell to a heartsick lady playwright whose most recent offspring had expired quietly in the cradle. You would only suppose this, however, if you didn’t know Gilbert.

Claire knew Gilbert.

And even if she were willing, in the hope of financial gain, to overlook his complete lack of talent, his nonexistent scruples and altogether tenuous grasp of reality, there remained still his most unique and troubling feature, i.e., the spectacular, almost supernatural rottenness of his luck.

Gilbert’s friends and victims have long debated what lies at the root of his uncanny knack for misfortune. Some feel it’s karmic payback for misdeeds in a previous life in which he must have been, at the very least, a Cossack. Others maintain that a touchy sorceress must have been given the bum’s rush at his christening. Whatever the reason, bad luck trails Gilbert like some relentless paparazzo. It dogs his footsteps, pops up where least expected, and rains disaster upon him and any hapless confederates he’s cajoled along for the ride. Twice in the past Claire had (thanks solely to me) become embroiled in Gilbert’s affairs with results ranging from mere humiliation to mortal peril. She was not eager as such to enlist for a third tour of duty, no matter how generous the signing bonus.

I understood her apprehension, feeling more than a shiver of it myself. But, convinced that my alternative was Milo and necktie land, I’d decided to view Gilbert’s previous debacles as a mere bad-luck streak that had, after all, to end sometime.

“I can’t believe,” I said, as we settled into our favorite booth at Carmine’s, “that you’re thinking of refusing this.”

“I can’t believe you’re not.”

“C’mon! This is exactly what we need! After all we’ve been through. The timing’s perfect!”

“That,” said Claire, “is what scares me. It’s so typical of Gilbert. He always oils around with these offers just when you’re at your most vulnerable. He’s like some—”

“Friend in need?”

“Opportunistic infection. And by the way, what’s this nonsense about him passing us off as a team? You don’t find that alarming?” asked Claire, who’d sooner have collaborated with Al Qaeda.

I replied that though a creative partnership with Gilbert was unlikely to prove the maxim that many hands make light the work, his motive for proposing it was obvious. He’d clearly used his formidable powers of persuasion to talk his way into a job, then, fearing himself not up to the task, drafted us as partners. “And a lucky thing for us, considering how bad we are at selling ourselves. Anyway,” I added, playing my strongest card, “I can’t wait to see the look on Marco’s face when he hears you’re scaling the heights in Hollywood.”

I could see that Claire had not yet viewed the matter from this perspective. Her scowl softened, and a smile, fleeting but unmistakable, played across her lips. As any wronged lover knows, success is the best revenge, and nothing stokes ambition like an unworthy ex begging to be left in the dust.

“He never took your career seriously. It’s one of the things I hated most about him.”

“It really is charming how willing you are to exploit my heartbreak for your own greedy purpose.”

“Your heartbreak,” I countered, “is half the reason we should go. What better time to take a free trip to Hollywood as guests of a real live mogul! We’ll blow town, see LA. We’ll party with Gilbert and his mom—whom you adore. We’ll find out what the job is and if you don’t like it you’ll fly home. First class! At best it’s a job, at worst a vacation, so cut the Cassandra routine and eat fast ’cause we need to pack.”

This tough-love approach, abetted by wine and more catty allusions to Marco, eventually won the day. She agreed to join me so long as I understood that she was not committing to anything whatsoever.

Her subsequent references that night to our “glittering new careers” were all made in the droll manner of a governess humoring her delusional charge. But for all her glib ironies I could detect in her quick smiles and flushed cheeks the first reluctant stirrings of hope. I knew that beneath that wry, guarded exterior she burned with the girlish desire to win some small sliver of Hollywood fame, then stab her sweetie in the eye with it.

My own optimism was less guarded and soared higher as the level in the wine bottle descended. I marveled at how my fortunes had rebounded and chided myself for my earlier pessimism. How absurd that a man of my gifts and obviously shining future had allowed himself to wallow in morbid, cravat-themed fantasies.

Swell talk show story though!

MY THOUGHTS WOULD NOT return again to old Milo until a bleak and drizzly afternoon the following February.

Gilbert and I, reeling from the latest in a seemingly endless string of catastrophes, had wandered numbly into the Beverly Hills Neiman Marcus in the preposterous hope that a spot of shopping might cheer us. We discovered a bar on the top floor and agreed that a cocktail might soothe our nerves and quiet the facial tic I’d recently developed.

As I nibbled morosely on my olive, I glanced up and noticed the necktie counter, where a well-dressed man about my age was meticulously arranging the latest merchandise. How cheerful he looked. How content to spend his days among so many pleasing fabrics and designs. How blissfully unencumbered by lawsuits and threats of imminent incarceration.

The song playing over the Muzak system ended, and another began, something old and familiar from South Pacific. I couldn’t place the title, but hearing it, I felt a sharp, inexplicable pang.

“What’s this song?” I asked Gilbert.

He listened a moment.

“‘This Nearly Was Mine.’ Why?”

Excerpted from My Lucky Star © Copyright 2012 by Joe Keenan. Reprinted with permission by LITTLE, BROWN. All rights reserved.

My Lucky Star

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316013358

- ISBN-13: 9780316013352