Excerpt

Excerpt

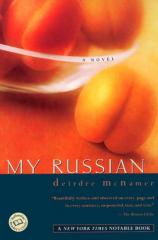

My Russian

ELEVEN BLOCKS from this darkened room, I have a husband and a handsome house. My bathrobe hangs from a hook in that house; my gardening clogs rest by the door; my furious son goes in and out, his demiwife in tow. In a drawer, in a desk, in that house, an itinerary tells them I fly home in a dozen days. The date is highlighted and starred.

When I leave this room, I wear a wig and some odd clothing I bought in Athens. Just like that, I've become a person who no longer fits the shape and color of my absent self, as it exists in the minds of my husband and son. They would look straight at this version of me and see no one they knew. I'm quite sure of that.

I am here to assess the situation. I'm here, let's say, to spy on my waiting life.

The couple next door in 202--pastel knits, running shoes--left this morning. They were here for a visit with a floundering daughter whose house is too cramped for guests. They liked the motel better anyway, because they could talk about her when they returned to the room each night. And the father could cough at alarming and luxurious length and no one would glance sideways, no one would prescribe. His wife stopped doing that decades ago.

They are the sort of old ones who seem to be melting--all the corners growing rounded, the head sagging forward, the body folding into itself in a whispery version of the way the lit-up monks folded themselves into their brilliant oblivion. Such a thing to think! But they keep coming to me, these illuminations of the ordinary people I call to mind. At this moment, yes, those old people sit on the edge of a bed worrying over a restaurant receipt, their white hair beginning to smoke.

Yesterday on the elevator they introduced themselves as Mary-Doris and Ed and told me the outlines of the situation with the daughter. Mary-Doris confided that she wouldn't mind walking around town a bit, get the kinks out, but Ed wouldn't do it. He has to drive everywhere. The rare times she gets him out walking, all he does is complain about the kinds of pets people keep, and the kinds of yards, and all the foreign cars. He worked for GM in Detroit for forty-five years and still wears his GM baseball cap.

As she told me about him, he watched her mildly, hands in his pockets. I seemed to know, looking at him, that he had no inter-mediary zone between his social self and his stark 4 A.M. self, no place in his mind to keep company with himself. You see these people on planes. They try small talk with the person next to them; it doesn't work; they eventually pick up the airline magazine and flip through it as if it's something that fell off the back of a truck.

Mary-Doris said that she had been a housekeeper for a family in Grosse Pointe for almost twenty years, that she had retired last year and what did I think they'd given her as a going-away present? Some stocks, I said. A gift certificate. A toaster oven. No, none of it. They had given her a papered bloodhound, worth a lot. But this dog ate so ravenously and was so nervy and big that she'd sold it for seventy-five dollars when they moved to their retirement house in Arizona. They called the creature the Disposer.

This morning I put on my taupe pantsuit and my walking shoes and my black wig, and I knocked at 202. I'd heard them moving around since six. I asked Mary-Doris if she wanted to go for a walk. She'd be good cover. She'd make me fully invisible.

I'm here, let's say, to correct the course of my life.

We walked slowly south, away form the Trocadero Motel and the interstate, and made our way into the university area with its spreading maples and its old Colonials, Tudors, viny bungalows. There stood my big house, windows flashing in the morning sun, the sprinklers sending up neat water fans. It looked serene and polished in that early light, as if it had never known trouble or had locked it away. The lawn was freshly mowed, and the clematis bloomed on the trellis. Behind the trellis stretched my landscaped yard, so carefully wild. The work of my Russian gardener.

He made a new yard, and then he was gone. And now it is up to us.

"There's a pretty place," said Mary-Doris, squinting for a longer look at my house. "That trellis looks a little raggedy, but nothing a few minutes with the snippers couldn't fix. Of course, these people hire the work done. Someone to design it all--someone to keep the weeds pulled." Then she told me about the rock garden she'd made around their modular house out there in the desert where they lived now. And I told her that I too hoped to have a garden someday, when I got my life back on track. She studied me.

Excerpted from My Russian © Copyright 2012 by Deirdre McNamer. Reprinted with permission by Ballantine. All rights reserved.

My Russian

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345439511

- ISBN-13: 9780345439512