Excerpt

Excerpt

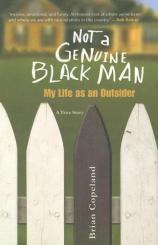

Not a Genuine Black Man: My Life as an Outsider

Chapter Five: Just a Trim

I didn’t venture far from home after the police episode. It wasn’t safe. I spent most of the rest of August in the apartment either reading my comics alone in my room, playing games with my sisters, or watching television. My self-imposed exile came to an end one Saturday, when Grandma announced that since school was starting soon, I’d need to get a haircut. Every new school year started with a haircut and a new pair of shoes. It was tradition. Grandma believed that these two things were the keys to success.

“As long as your head and your feet look all right, you okay,” she’d say.

I had a regular barber in Oakland. Mr. Johnson at Johnson’s Barbershop had been cutting my hair since I was a first grader. His son Joseph and I had been in class together. So when it came time for me to get a trim, we patronized his place.

I grabbed a couple of comic books to read while I waited for my turn in the chair and announced, “Okay, I’m ready to go see Mr. Johnson.”

“I don’t want you to go to Mr. Johnson’s anymore,” Mom said.

“Why?”

“We live in a new community and we need to support the merchants here,” she said. “Suer, find someplace to get his hair cut in San Leandro.”

“Shit,” Grandma said as she opened the front door and headed to the car with me in tow.

Grandma started the engine, backed our new Chevrolet Malibu out of its parking stall, and headed toward the street. She stopped at the driveway entrance and began to turn right. Suddenly she slammed on the brakes. A late model sedan sped up the street right in front of us. As it passed, the pretty young white woman behind the wheel rolled down her window and screamed, “Go back to Oakland!”

“You go to shit!” Grandma yelled back.

I wanted to go back inside. I started to think that this was a bad idea.

“Where are we going, Grandma?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you know where the barbershops are around here?”

“Boy, I said, ‘I don’t know’!” she snapped.

I knew to shut up when she got like this. I was quiet as she headed toward the downtown area. Soon we saw a shopping center. Grandma parked and we got out. She grabbed me by the wrist with a viselike grip. Grandma never held my hand, she held my wrist. She said, “That way you can’t run no place.” We walked around the center until we saw the red and white swirl of a barber pole. We walked into an environment so sterile it looked like a NASA decontamination chamber. Everything looked spit-shined. The chrome was sparkling and the mirrors and glass didn’t have a smudge or a fingerprint on them. Even though the barber chairs were full and the barbers were furiously working away, there wasn’t any hair on the floor. I’d never seen anything like it.

There was a boisterous chatter as Grandma and I walked in. There was laughing, talking, and storytelling amid the buzz of the electric clipper and the snip snip snipping of scissors. It was a symphony orchestra of various voices and sounds. A symphony that stopped the second we set foot inside the door. It was like those old commercials where E.F. Hutton just spoke and everybody wanted to hear what it was that he was going to say. The entire sea of white faces seemed to be waiting for some words of wisdom from us.

A gray-haired barber in a blue smock abruptly stopped cutting the hair of the little boy perched in a red removable riser on the barber chair. He shut off the clippers and held them suspended in midair as he looked us over. Then… he smiled.

“May I help you?” he said, the word “help” taking on a friendliness in the tone he used.

Grandma didn’t smile. She looked back at him, hard, stern.

“He need to get his hair cut,” she said in her no-nonsense way.

“I’m sorry,” the barber said, still smiling. “We don’t cut his kind of hair.”

He pointed to a sign on the wall that read, no naturals, no relaxers. Why didn’t the signs just say, no blacks or art garfunkels allowed?

“We don’t know how to cut that type of hair,” he said, still smiling.

I could feel the stares of the other patrons boring into me, each set of eyes a pair of hot, miniature drills cutting me, searing me.

“Can’t help you,” he continued. “Sorry.”

Grandma’s grip on my wrist tightened as she turned on her heels and headed back out the door.

“You might try one of the shops in Oakland,” I heard him call out as the din of the symphony resumed.

Grandma was quiet as she stomped back to the Malibu.

“Shit,” I heard her mutter under her breath.

We spent the next hour driving around town, stopping at every barber pole we saw. Some barbers smiled like the first guy. Some were icy. The tone and the words were different but at the same time identical in meaning.

“Can’t help you.”

“I can’t handle his hair.”

“We don’t know how to cut that.”

“I’d try one of the places over in Oakland.”

“Shit,” Grandma said over and over again.

She pointed the car north, drove up to MacArthur Boulevard, and headed toward the city limits.

“Go back to Oakland!” that white woman had shouted from her car window. “Go back to where you belong.”

At the Oakland/San Leandro border, there was a noticeable difference in the way that the streets were kept. Upon crossing the line into Oakland, the sidewalk turned from disinfected, antiseptic cleanliness to urban disarray. Where there had been spotless, steam-cleaned streets, there was now a morass of broken glass. Discarded paper and trash lined the street, right up to the entering San Leandro sign. It was as though even the refuse knew that it was okay to clutter the streets of Oakland, as long as it didn’t breach the invisible wall.

The cars parked along MacArthur were old. The faces of the pedestrians changed. They went from shades ranging from lily white and pink to various hues of brown. Light brown, dark brown, ebony. Some as black as tar.

We found a place in front of Mr. Johnson’s shop, parked, and went in. We heard the loud voices the second we got out of the car. It was a din like that in the barbershops across the border that we’d just visited, but I immediately noticed that there was something different here. It was dissimilar in a way that I couldn’t really describe. Their laughter was rich. The voices were louder, more coarse. They argued and talked over one another with forthrightness. There was animated vulgarity.

There was also an odor. The other shops had no smell. Breathing in them was like taking a big whiff from a head of lettuce. In here, there was a fragrance. The aroma of strong cologne, shaving cream, hair relaxing chemicals, Dixie Peach hair pomade, and burned hair. It didn’t exactly smell bad, but it was no bouquet of roses either.

A middle-aged black man stood in the center of the shop, flailing his arms about as his voice got higher and louder. He was dressed poorly. Whereas the patrons in the San Leandro shops were neatly groomed, even before their hair was trimmed, this man was disheveled. He had a head of long, nappy hair that looked dirty even from my vantage point. His face sported a ragged, uneven beard. He wore a sweatshirt that was so dirty it looked like it could have crawled onto his lean frame by itself. As he pontificated, I noticed the yellow glint of gold from one of his front teeth. The other front tooth was missing.

“You can’t trust any of those motherfuckers,” he shouted.

Mr. Johnson looked up from the head he was shearing as Grandma and I walked in.

“Watch your mouth,” he said to the man. “We got kids in here.”

“It ain’t like he ain’t heard this shit before. Is it boy?” he said to me.

I didn’t know what to say. I had heard the word “motherfucker” before. Sylvester was my father, after all. I looked at the man and shrugged.

“He need to get his hair cut for school,” Grandma said, rescuing me.

“All right. I’ll get to him in a minute,” Mr. Johnson said, his clippers shaving a tiny wedge of gray hair from the head of the elderly gentleman sitting in his barber chair.

As Grandma and I sat down, I opened one of my Superboy comics and began to read.

“What you reading, young man?” the gold-toothed wonder asked.

“Superboy.”

Of all my comic book heroes, Superboy would grow to become my favorite. We related to each other. Here was a boy who was truly the only one of his kind in the universe. There was no one else remotely like him. No one with whom he could talk with a common frame of reference. He was just like me. I lived in a house with all females. There were no black men in my life, certainly no black men who could understand what it was like to be the only black male in a room, a store, or on a street.

In his guise as young Clark Kent, Superboy had to go to Smallville High and pretend he was just like everybody else. Worse, he had to pretend to be less than everybody else, lest they suspect his secret true identity and be afraid of him. He pretended to be weaker than he was. He pretended to be afraid of spiders. He would deliberately miss questions on tests so as not to get perfect scores and stand out. He longed to belong. He longed for normalcy. Just like me.

“Superboy? He’s white, ain’t he? What you reading about white boys for?”

“Leave him alone,” Mr. Johnson said.

“I’m just talking to the young man.” He turned to me.

“Why don’t you read some books about brothers?”

I shrugged again.

“See?” he said, gesticulating wildly again. “They got our kids so messed up they don’t even know why they do half the shit they do.”

“Who is ‘they’?” I asked, already sorry that I’d opened my mouth.

I know that there are times when you should never ask questions, because you’ll regret it. Never ask old people how they are, because they’ll tell you. Every ailment, every ache and pain, every grievance they have with their son who doesn’t call and their daughter who wants to put them in the home. This guy was one of those. He wasn’t exactly old, but I knew that now he’d never shut up.

“Who,” he said, “is the white folks. The crackers. The peckerwoods. Ofays. Whitey. The Man.”

“I said to leave the boy alone,” Mr. Johnson said again.

“Why can’t I talk to the young man? I might be able to teach him something. Young man, what’s your name?”

“Brian.”

“Okay, Brian. Let me tell you something. There ain’t no white man who is worth a shit. They are your enemy. They will keep a nigger down any chance they get.”

“I don’t think that’s true.” Why can’t I just shut up so he will, too?

“Name me one white man who’s worth a goddamn.”

I paused for a moment to think. My experiences with white men hadn’t exactly been positive as of late.

“How about George Washington? What about all of those people they put on money? They had to be good to be put on money.”

Here we go.

“Money?” He laughed. “Money? Let me tell you something young man. When people talk about a fistful of dollars, they really should be talking about a fistful of bigots. That’s all they holding in they’re hands. A bunch of bigoted, good for nothing motherfuckers.”

“I don’t want to have to tell you again to watch your mouth in here, Lester,” Mr. Johnson said, getting mad. His name was Lester. He looked like a Lester. It’s weird when people fit their names.

“Okay, okay,” Lester said. “Just let me educate y’all. School is officially open. Now, young man. Who is on the hundred dollar bill?”

I had just seen my first hundred. When I went to the bank with Mom to cash her paycheck, they gave her one. She let me hold it. It looked and smelled different from other money. I wanted them. Lots of them.

“Benjamin Franklin,” I answered.

“Benjamin Franklin,” Lester said. “Inventor of the lightning rod, inventor of the bifocals, inventor of the Franklin stove. Racist bastard. He had slaves.”

“No, he did not!” the old man in the barber chair protested.

“Read your history. He had slaves. Two of ’em. Man and a woman. Woman was actually named Jemima. Motherfucker must have liked pancakes. The only reason that kite he flew in the lightning storm had a key on the end of it was because he couldn’t find a nigger small enough to tie on there. Racist.” The man in the chair rolled his eyes.

“Who is on the fifty?” Lester asked, turning to me. I knew this one, too. I’d actually had a fifty once. I took all of my birthday money, added it to my chore money, and had it changed for a fifty. I carried it around in my pocket for four months before I finally broke it. It was fun saying, “All I have is a fifty.”

“President Grant,” I shouted, like I was winning a game show quiz.

He nodded.

“Ulysses Simpson Grant. President of the United States. General of the Union Army, fighting for the rights of all them poor slaves. That’s what they taught you in school, ain’t it? Well, what they didn’t teach you is that slaves wiped his sorry ass from the day he was born until he went in the army. Once he was in there, his ass was too drunk to know who the fuck he was helping free.”

“You are amazing,” Mr. Johnson said with disgust.

“The twenty?” he asked me.

“Andrew Jackson,” I shouted. I was even amazing myself. I didn’t know I knew so much about money.

“Old Hickory,” Lester intoned. “He didn’t have slaves.

That’s because he was too busy killing every motherfucking Indian he could find. You kill enough Indians, boy, and maybe they’ll put your ass on the twenty.”

“Alexander Hamilton is on the ten-dollar bill,” I volunteered. “Secretary of the Treasury. Shot to death by Vice President Aaron Burr. The only vice president to actually do something. Most of ’em just go to funerals. This motherfucker caused funerals.”

“Now, I happen to know,” the man in the barber chair said,“that Alexander Hamilton did not own slaves. In fact, he was opposed to slavery.”

“That’s right,” Lester shouted. “He was against slavery. But did he say anything about it? Nope. Nothing. Not a goddamned word. He wanted to be secretary of the Treasury.

“Hmm,” Lester mocked. “Let me think. I can talk about what bullshit slavery is, or I can have a government job. You niggers better go sing some more spirituals.”

Mr. Johnson again rolled his eyes. He’d given up.

“What about the five-dollar bill?” I asked.

Lester stopped dead in his tracks. He was actually silent for a moment.

“Let’s talk about the two-dollar bill,” he said.

“They don’t even make two-dollar bills anymore!” the man in the chair shouted.

Lester ignored him.

“Thomas Jefferson. Third president of the United States. Author of the Declaration of Independence. Son of a bitch not only had slaves, he fucked ’em. Repeatedly. Had kids with them. Not that his continental ass would publicly own up to any of them.”

“Lester,” Mr. Johnson said, trying hard to control his growing fury, “you use that word in here one more time and you are out the door. I mean it.”

“Okay, okay,” he said. “Thomas Jefferson. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal . . . ’cept niggers. Jefferson had black kids. They had to work for his ass for free though. His slaves weren’t even set free when he died. They went to pay off his debts. How’d you like that, boy? Having your ass used to pay off some white man’s I.O.U.”

“George Washington was still a great man,” I said. “He was the first president.”

“Yep,” Lester says. “First president. General of the continental army. Signer of the Declaration of Independence. Tobacco farmer. And who do you think was farming that tobacco while he was doing all that shit? Niggers.”

He stood on the chair next to me as if it were a stage.

“George, did you chop down that cherry tree?” he said. “Father, I cannot tell a lie. The niggers did it!”

The man in the chair shook his head.

“Lester, you are just impossible.”

“No, I’m honest. White men ain’t worth a shit.”

He climbed down off of the chair and started for the door.

“I’ll see you uneducated motherfuckers later. I’m leaving so I can say it,” he said before Mr. Johnson could protest.

He got to the doorway, walked out, and then turned around and came back in.

“Can somebody lend me a dollar?”

An hour later, I walked into the apartment, my hair neatly cut.

“It looks great!” My mother beamed. “Where did you take him, Suer?”

“To Mr. Johnson’s shop.”

“What? I told you to take him someplace here in San Leandro.”

“There ain’t no place in San Leandro,” she shouted.

“Do you mean to tell me that there isn’t a barbershop in the whole city?”

“Not that will work on black boys.”

My mother fell silent. She looked at the floor for a moment, then sighed a deep sigh. A cleansing breath for her soul. After what seemed like an eternity, she spoke.

“You look nice, Brian.”

Excerpted from Not a Genuine Black Man © Copyright 2012 by Brian Copeland. Reprinted with permission by Macadam/Cage. All rights reserved.

Not a Genuine Black Man: My Life as an Outsider

- paperback: 250 pages

- Publisher: MacAdam/Cage

- ISBN-10: 1596923113

- ISBN-13: 9781596923119