Excerpt

Excerpt

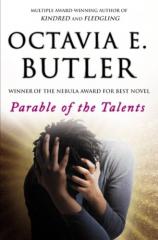

Parable of the Talents

ONE

From EARTHSEED: THE BOOKS OF THE LIVING

-

Darkness

Gives shape to the light

As light

Shapes the darkness.

Death

Gives shape to life

As life

Shapes death.

The universe

And God

Share this wholeness,

Each

Defining the other.

God

Gives shape to the universe

As the universe

Shapes God.

FROM Memories of Other Worlds

By Taylor Franklin Bankole

I have read that the period of upheaval that journalists have begun to refer to as "the Apocalypse" or more commonly, more bitterly, "the Pox" lasted from 2015 through 2030—a decade and a half of chaos. This is untrue. The Pox has been a much longer torment. It began well before 2015, perhaps even before the turn of the millennium. It has not ended.

I have also read that the Pox was caused by accidentally coinciding climatic, economic, and sociological crises. It would be more honest to say that the Pox was caused by our own refusal to deal with obvious problems in those areas. We caused the problems: then we sat and watched as they grew into crises. I have heard people deny this, but I was born in 1970. I have seen enough to know that it is true. I have watched education become more a privilege of the rich than the basic necessity that it must be if civilized society is to survive. I have watched as convenience, profit, and inertia excused greater and more dangerous environmental degradation. I have watched poverty, hunger, and disease become inevitable for more and more people.

Overall, the Pox has had the effect of an installment-plan World War III. In fact, there were several small, bloody shooting wars going on around the world during the Pox. These were stupid affairs—wastes of life and treasure. They were fought, ostensibly, to defend against vicious foreign enemies. All too often, they were actually fought because inadequate leaders did not know what else to do. Such leaders knew that they could depend on fear, suspicion, hatred, need, and greed to arouse patriotic support for war.

Amid all this, somehow, the United States of America suffered a major nonmilitary defeat. It lost no important war, yet it did not survive the Pox. Perhaps it simply lost sight of what it once intended to be, then blundered aimlessly until it exhausted itself.

What is left of it now, what it has become, I do not know.

Taylor Franklin Bankole was my father. From his writings, he seems to have been a thoughtful, somewhat formal man who wound up with my strange, stubborn mother even though she was almost young enough to be his granddaughter.

My mother seems to have loved him, seems to have been happy with him. He and my mother met during the Pox when they were both homeless wanderers. But he was a 57-year-old doctor—a family practice physician—and she was an 18-year-old girl. The Pox gave them terrible memories in common. Both had seen their neighborhoods destoyed—his in San Diego and hers in Robledo, a suburb of Los Angeles. That seems to have been enough for them. In 2027, they met, liked each other, and got married. I think, reading between the lines of some of my father's writing, that he wanted to take care of this strange young girl that he had found. He wanted to keep her safe from the chaos of the time, safe from the gangs, drugs, slavery, and disease. And of course he was flattered that she wanted him. He was human, and no doubt tired of being alone. His first wife had been dead for about two years when they met.

He couldn't keep my mother safe of course. No one could have done that. She had chosen her path long before they met. His mistake was in seeing her as a young girl. She was already a missile, armed and targeted.

FROM The Journals of Lauren Oya Olamina

Sunday, September 26, 2032

Today is Arrival Day, the fifth anniversary of our establishing a community called Acorn here in the mountains of Humboldt County.

In perverse celebration of this, I've just had one of my recurring nightmares. They've become rare in the past few years—old enemies with familiar nasty habits. I know them. They have such soft, easy beginnings. . . . This one was, at first, a visit to the past, a trip home, a chance to spend time with beloved ghosts.

******

My old home has come back from the ashes. This doesn't surprise me, somehow, although I saw it burn years ago. I walked through the rubble that was left of it. Yet here it is restored and filled with people—all the people I knew as I was growing up. They sit in our front rooms in rows of old metal folding chairs, wooden kitchen and dining room chairs, and plastic stacking chairs, a silent congregation of the scattered and the dead.

Church service is already going on, and, of course, my father is preaching. He looks as he always has in his church robes: tall, broad, stern, straight—a great black wall of a man with a voice you not only hear, but feel on your skin and in your bones. There's no corner of the meeting rooms that my father cannot reach with that voice. We've never had a sound system—never needed one. I hear and feel that voice again.

Yet how many years has it been since my father vanished? Or rather, how many years since he was killed? He must have been killed. He wasn't the kind of man who would abandon his family, his community, and his church. Back when he vanished, dying by violence was even easier than it is today. Living, on the other hand was almost impossible.

He left home one day to go to his office at the college. He taught his classes by computer, and only had to go to the college once a week, but even once a week was too much exposure to danger. He stayed overnight at the college as usual. Early mornings were the safest times for working people to travel. He started for home the next morning and was never seen again.

We searched. We even paid for a police search. Nothing did any good.

This happened many months before our house burned, before our community was destroyed. I was 17. Now I'm 23 and I'm several hundred miles from that dead place.

Yet all of a sudden, in my dream, things have come right again. I'm at home, and my father is preaching. My stepmother is sitting behind him and a little to one side at her piano. The congregation of our neighbors sits before him in the large, not-quite-open area formed by our living room, dining room, and family room. This is a broad L-shaped space into which even more than the usual 30 or 40 people have crammed themselves for Sunday service. These people are too quiet to be a Baptist congregation—or at least, they're too quiet to be the Baptist congregation I grew up in. They're here, but somehow not here. They're shadow people. Ghosts.

Only my own family feels real to me. They're as dead as most of the others, and yet they're alive! My brothers are here and they look the way they did when I was about 14. Keith, the oldest of them, the worst and the first to die, is only 11. This means Marcus, my favorite brother and always the best-looking person in the family, is 10. Ben and Greg, almost as alike as twins, are eight and seven. We're all sitting in the front row, over near my stepmother so she can keep an eye on us. I'm sitting between Keith and Marcus to keep them from killing each other during the service.

When neither of my parents is looking, Keith reaches across me and punches Marcus hard on the thigh. Marcus, younger, smaller, but always stubborn, always tough, punches back. I grab each boy's fist and squeeze. I'm bigger and stronger than both of them and I've always had strong hands. The boys squirm in pain and try to pull away. After a moment, I let them go. Lesson learned. They let each other alone for at least a minute or two.

In my dream, their pain doesn't hurt me the way it always did when we were growing up. Back then, since I was the oldest, I was held responsible for their behavior. I had to control them even though I couldn't escape their pain. My father and stepmother cut me as little slack as possible when it came to my hyperempathy syndrome. They refused to let me be handicapped. I was the oldest kid, and that was that. I had my responsibilities. Nevertheless I used to feel every damned bruise, cut, and burn that my brothers managed to collect. Each time I saw them hurt, I shared their pain as though I had been injured myself. Even pains they pretended to feel, I did feel. Hyperempathy syndrome is a delusional disorder, after all. There's no telepathy, no magic, no deep spiritual awareness. There's just the neurochemically-induced delusion that I feel the pain and pleasure that I see others experiencing. Pleasure is rare, pain is plentiful, and, delusional or not, it hurts like hell.

So why do I miss it now?

What a crazy thing to miss. Not feeling it should be like having a toothache vanish away. I should be surprised and happy. Instead, I'm afraid. A part of me is gone. Not being able to feel my brothers' pain is like not being able to hear them when they shout, and I'm afraid.

The dream begins to become a nightmare.

Without warning, my brother Keith vanishes. He's just gone. He was the first to go—to die—years ago. Now he's vanished again. In his place beside me, there is a tall, beautiful woman, black-brown-skinned and slender with long, crow-black hair, gleaming. She's wearing a soft, silky green dress that flows and twists around her body, wrapping her in some intricate pattern of folds and gathers from neck to feet. She is a stranger.

She is my mother.

She is the woman in the one picture my father gave me of my biological mother. Keith stole it from my bedroom when he was nine and I was twelve. He wrapped it in an old piece of a plastic tablecloth and buried it in our garden between a row of squashes and a mixed row of corn and beans. Later, he claimed it wasn't his fault that the picture was ruined by water and by being walked on. He only hid it as a joke. How was he supposed to know anything would happen to it? That was Keith. I beat the hell out of him. I hurt myself too, of course, but it was worth it. That was one beating he never told our parents about.

But the picture was still ruined. All I had left was the memory of it. And here was that memory, sitting next to me.

My mother is tall, taller than I am, taller than most people. She's not pretty. She's beautiful. I don't look like her. I look like my father, which he used to say was a pity. I don't mind. But she is a stunning woman. I stare at her, but she does not turn to look at me. That, at least, is true to life. She never saw me. As I was born, she died. Before that, for two years, she took the popular "smart drug" of her time. It was a new prescription medicine called Paracetco, and it was doing wonders for people who had Alzheimer's disease. It stopped the deterioration of their intellectual function and enabled them to make excellent use of whatever memory and thinking ability they had left. It also boosted the performance of ordinary, healthy young people. They read faster, retained more, made more rapid, accurate connections, calculations, and conclusions. As a result, Paracetco became as popular as coffee among students, and, if they meant to compete in any of the highly paid professions, it was as necessary as a knowledge of computers.

My mother's drug taking may have helped to kill her. I don't know for sure. My father didn't know either. But I do know that her drug left its unmistakable mark on me—my hyperempathy syndrome. Thanks to the addictive nature of Paracetco—a few thousand people died trying to break the habit—there were once tens of millions of us.

Hyperempaths, we're called, or hyperempathists, or sharers. Those are some of the polite names, And in spite of our vulnerability and our high mortality rate, there are still quite a few of us.

I reach out to my mother. No matter what she's done, I want to know her. But she won't look at me. She won't even turn her head. And somehow, I can't quite reach her, can't touch her. I try to get up from my chair, but I can't move. My body won't obey me. I can only sit and listen as my father preaches.

Now I begin to know what he is saying. He has been an indistinct background rumble until now, but now I hear him reading from the twenty-fifth chapter of Matthew, quoting the words of Christ:

" 'For the kingdom of Heaven is as a man traveling into a far country who called his own servants, and delivered unto them his goods. And unto One he gave five talents, to another two, and to another one; to every man according to his several ability; and straightway took his journey.' "

My father loved parables—stories that taught, stories that presented ideas and morals in ways that made pictures in people's minds. He used the ones he found in the Bible, the ones he plucked from history, or from folk tales, and of course he used those he saw in his life and the lives of people he knew. He wove stories into his Sunday sermons, his Bible classes, and his computer-delivered history lectures. Because he believed stories were so important as teaching tools, I learned to pay more attention to them than I might have otherwise. I could quote the parable that he was reading now, the parable of the talents. I could quote several Biblical parables from memory. Maybe that's why I can hear and understand so much now. There is preaching between the bits of the parable, but I can't quite understand it. I hear its rhythms rising and falling, repeating and varying, shouting and whispering. I hear them as I've always heard them, but I can't catch the words—except for the words of the parable.

" 'Then he that had received the five talents went and traded with the same and made them another five talents. And likewise he that had received two, he also gained another two. But he that had received one went out and digged in the earth, and hid his lord's money.' "

My father was a great believer in education, hard work, and personal responsibility. "Those are our talents," he would say as my brothers' eyes glazed over and even I tried not to sigh. "God has given them to us, and he'll judge us according to how we use them."

The parable continues. To each of the two servants who had traded well and made profit for their lord, the lord said, " 'Well done, thou good and faithful servant; thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy lord.' "

But to the servant who had done nothing with his silver talent except bury it in the ground to keep it safe, the lord said harsher words . " 'Thou wicked and slothful servant . . .' " he began. And he ordered his men to, " 'Take therefore the talent from him and give it unto him which hath ten talents. For unto everyone that hath shall be given, and he shall have in abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.' "

When my father has said these words, my mother vanishes. I haven't even been able to see her whole face, and now she's gone.

I don't understand this. It scares me. I can see now that other people are vanishing too. Most have already gone. Beloved ghosts. . . .

My father is gone. My stepmother calls out to him in Spanish the way she did sometimes when she was excited, "No! How can we live now? They'll break in. They'll kill us all! We must build the wall higher!"

And she's gone. My brothers are gone. I'm alone—as I was alone that night five years ago. The house is ashes and rubble around me. It doesn't burn or crumble or even fade to ashes, but somehow, in an instant, it is a ruin, open to the night sky. I see stars, a quarter moon, and a streak of light, moving, rising into the sky like some life force escaping. By the light of all three of these, I see shadows, large, moving, threatening. I fear these shadows, but I see no way to escape them. The wall is still there, surrounding our neighborhood, looming over me much higher than it ever truly did. So much higher. . . . It was supposed to keep danger out. It failed years ago. Now it fails again. Danger is walled in with me. I want to run, to escape, to hide, but now my own hands, my feet begin to fade away. I hear thunder. I see the streak of light rise higher in the sky, grow brighter.

Then I scream. I fall. Too much of my body is gone, vanished away. I can't stay upright, can't catch myself as I fall and fall and fall. . . .

******

I awoke here in my cabin at Acorn, tangled in my blankets, half on and half off my bed. Had I screamed aloud? I didn't know. I never seem to have these nightmares when Bankole is with me, so he can't tell me how much noise I make. It's just as well. His practice already costs him enough sleep, and this night must be worse than most for him.

It's three in the morning now, but last night, just after dark, some group, some gang, perhaps, attacked the Dovetree place just north of us. There were, yesterday at this time, 22 people living at Dovetree—the old man, his wife, and his two youngest daughters; his five married sons, their wives and their kids. All of these people are gone except for the two youngest wives and the three little children they were able to grab as they ran. Two of the kids are hurt, and one of the women has had a heart attack, of all things. Bankole has treated her before. He says she was born with a heart defect that should have been taken care of when she was a baby. But she's only twenty, and around the time she was born, her family, like most people, had little or no money. They worked hard themselves and put the strongest of their kids to work at ages eight or ten. Their daughter's heart problem was always either going to kill her or let her live. It wasn't going to be fixed.

Now it had nearly killed her. Bankole was sleeping—or more likely staying awake—in the clinic room of the school tonight, keeping an eye on her and the two injured kids. Thanks to my hyperempathy syndrome, he can't have his clinic here at the house. I pick up enough of other people's pain as things are, and he worries about it. He keeps wanting to give me some stuff that prevents my sharing by keeping me sleepy, slow, and stupid. No, thanks!

So I awoke alone, soaked with sweat, and unable to get back to sleep. It's been years since I've had such a strong reaction to a dream. As I recall, the last time was five years ago right after we settled here, and it was this same damned dream. I suppose it's come back to me because of the attack on Dovetree.

That attack shouldn't have happened. Things have been quieting down over the past few years. There's still crime, of course—robberies. break-ins, abductions for ransom or for the slave trade. Worse, the poor still get arrested and indentured for indebtedness, vagrancy, loitering, and other "crimes." But this thing of raging into a community and killing and burning all that you don't steal seems to have gone out of fashion. I haven't heard of anything like this Dovetree raid for at least three years.

Granted, the Dovetrees did supply the area with home-distilled whiskey and homegrown marijuana, but they've been doing that since long before we arrived. In fact, they were the best-armed farm family in the area because their business was not only illegal, but lucrative. People have tried to rob them before, but only the quick, quiet burglar-types have had any success. Until now.

I questioned Aubrey, the healthy Dovetree wife, while Bankole was working on her son. He had already told her that the little boy would be all right, and I felt that we had to find out what she knew, no matter how upset she was. Hell, the Dovetree houses are only an hour's walk from here down the old logging road. Whoever hit Dovetree, we could be next on their list. Aubrey told me the attackers wore strange clothing, She and I talked in the main room of the school, a single, smoky oil lamp between us on one of the tables. We sat facing one another across the table, Aubrey glancing every now and then at the clinic room, where Bankole had cleaned and eased her child's scrapes, burns, and bruises. She said the attackers were men, but they wore belted black tunics—black dresses, she called them—which hung to their thighs. Under these, they wore ordinary pants—either jeans or the kind of camouflage pants that she had seen soldiers wear.

"They were like soldiers," she said. "They sneaked in, so quiet. We never saw them until they started shooting at us. Then, bang! All at once. They hit all our houses. It was like an explosion—maybe twenty or thirty or more guns going off all at just the same time."

And that wasn't the way gangs operated. Gangsters would have fired raggedly, not in unison. Then they would have tried to make individual names for themselves, tried to grab the best-looking women or steal the best stuff before their friends could get it.

"They didn't steal or burn anything until they had beaten us, shot us." Aubrey said. "Then they took our fuel and went straight to our fields and burned our crops. After that, they raided the houses and barns. They all wore big white crosses on their chests—crosses like in church. But they killed us. They even shot the kids. Everybody they found, they killed them. I hid with my baby or they would have shot him and me." Again, she stared toward the clinic room.

That killing of children . . . that was a hell of a thing. Most thugs—except for the worst psychotics—would keep the kids alive for rape and then for sale. And as for the crosses, well, gangsters might wear crosses on chains around their necks, but that wasn't the sort of thing most of their victims would get close enough to notice. And gangsters were unlikely to run around in matching tunics all sporting white crosses on their chests. This was something new.

Or something old.

I didn't think of what it might be until after I had let Aubrey go back to the clinic to bed down next to her child. Bankole had given him something to help him sleep. He did the same for her, so I won't be able to ask her anything more until she wakes up later this morning. I couldn't help wondering, though, whether these people, with their crosses, had some connection with my current least favorite presidential candidate, Texas Senator Andrew Steele Jarret. It sounds like the sort of thing his people might do—a revival of something nasty out of the past. Did the Ku Klux Klan wear crosses—as well as burn them? The Nazis wore the swastika, which is a kind of cross, but I don't think they wore it on their chests. There were crosses all over the place during the Inquisition and before that, during the Crusades. So now we have another group that uses crosses and slaughters people. Jarret's people could be behind it. Jarret insists on being a throwback to some earlier, "simpler" time. Now does not suit him. Religious tolerance does not suit him. The current state of the country does not suit him. He wants to take us all back to some magical time when everyone believed in the same God, worshipped him in the same way, and understood that their safety in the universe depended on completing the same religious rituals and stomping anyone who was different There was never such a time in this country. But these days when more than half the people in the country can't read at all, history is just one more vast unknown to them. Jarret supporters have been known, now and then, to form mobs and burn people at the stake for being witches. Witches! In 2032! A witch, in their view, tends to be a Moslem, a Jew, a Hindu, a Buddhist, or, in some parts of the country, a Mormon, a Jehovah's Witness, or even a Catholic. A witch may also be an atheist, a "cultist," or a well-to-do eccentric. Well-to-do eccentrics often have no protectors or much that's worth stealing. And "cultist" is a great catchall term for anyone who fits into no other large category, and yet doesn't quite match Jarret's version of Christianity. Jarret's people have been known to beat or drive out Unitarians, for goodness' sake. Jarret condemns the burnings, but does so in such mild language that his people are free to hear what they want to hear. As for the beatings, the tarring and feathering, and the destruction of "heathen houses of devil-worship," he has a simple answer: "Join us! Our doors are open to every nationality, every race! Leave your sinful past behind, and become one of us. Help us to make America great again." He's had notable success with this carrot-and-stick approach. Join us and thrive, or whatever happens to you as a result of your own sinful stubbornness is your problem. His opponent Vice President Edward Jay Smith calls him a demagogue, a rabble-rouser, and a hypocrite. Smith is right, of course, but Smith is such a tired, gray shadow of a man. Jarret, on the other hand, is a big, handsome, black-haired man with deep, clear blue eyes that seduce people and hold them. He has a voice that's a whole-body experience, the way my father's was. In fact, I'm sorry to say, Jarret was once a Baptist minister like my father. But he left the Baptists behind years ago to begin his own "Christian America" denomination. He no longer preaches regular CA sermons at CA churches or on the nets, but he's still recognized as head of the church.

It seems inevitable that people who can't read are going to lean more toward judging candidates on the way they look and sound than on what they claim they stand for. Even people who can read and are educated are apt to pay more attention to good looks and seductive lies than they should. And no doubt the new picture ballots on the nets will give Jarret an even greater advantage.

Jarret's people see alcohol and drugs as Satan's tools. Some of his more fanatical followers might very well be the tunic-and-cross gang who destroyed Dovetree.

And we are Earthseed. We're "that cult," "those strange people in the hills," "those crazy fools who pray to some kind of god of change." We are also, according to some rumors I've heard, "those devil-worshiping hill heathens who take in children. And what do you suppose they do with them?" Never mind that the trade in abducted or orphaned children or children sold by desperate parents goes on all over the country, and everyone knows it. No matter. The hint that some cult is taking in children for "questionable purposes" is enough to make some people irrational.

That's the kind of rumor that could hurt us even with people who aren't Jarret supporters. I've only heard it a couple of times, but it's still scary.

At this point, I just hope that the people who hit Dovetree were some new gang, disciplined and frightening, but only after profit. I hope. . . . But I don't believe it. I do suspect that Jarret's people had something to do with this. And I think I'd better say so today at Gathering. With Dovetree fresh in everyone's mind, people will be ready to cooperate, have more drills and scatter more caches of money, food, weapons, records, and valuables. We can fight a gang. We've done that before when we were much less prepared than we are now. But we can't fight Jarret. In particular, we can't fight President Jarret. President Jarret, if the country is mad enough to elect him, could destroy us without even knowing we exist.

We are now 59 people—64 with the Dovetree women and children, if they stay. With numbers like that, we barely do exist. All the more reason, I suppose, for my dream.

My "talent," going back to the parable of the talents, is Earthseed. And although I haven't buried it in the ground, I have buried it here in these coastal mountains, where it can grow at about the same speed as our redwood trees. But what else could I have done? If I had somehow been as good at rabble-rousing as Jarret is, then Earthseed might be a big enough movement by now to be a real target. And would that be better?

I'm jumping to all kinds of unwarranted conclusions. At least I hope they're unwarranted. Between my horror at what's happened down at Dovetree and my hopes and fears for my own people, I'm upset and at loose ends and, perhaps, just imagining things.

© 1999 by Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Talents

- paperback: 424 pages

- Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-10: 0446675784

- ISBN-13: 9780446675789