Excerpt

Excerpt

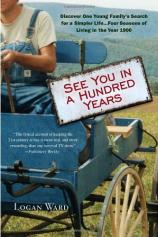

See You in a Hundred Years: One Young Family's Search for a Simpler Life

Chapter One

Goodbye, New York

In the City, you don't stargaze. You don't dig through wildflower field guides for the name of that brilliant trumpet burst of blue you saw on your morning walk. You don't hunt for animal tracks in the snow or pause in that same frozen forest, eyes closed, listening for the chirp of a foraging nuthatch. You forget such a creature as a snake even exists. It's as if New York is encased in a big plastic bubble, where humans sit atop the food chain armed with credit cards and Zagat guides. Native wildlife? Cockroaches, pigeons, rats. Disease transmitters. Boat payments for exterminators. Our story begins in the bubble.

The year is 2000, the dawn of a new millennium. The Y2K scare is barely behind us. Economic good times lie ahead, with unemployment at an all-time low, the U.S. government boasting record surpluses, and the NASDAQ composite index raising a lusty cheer by topping 5,000. The stock market is making everyone rich—at least on paper. Living in the wealthiest city in the wealthiest nation at the wealthiest moment in history, Heather and I should be happy. We aren't.

Which is why I find myself in the back of a cab one day, lurching down Park Avenue, all bottled up with excitement over the news I carry. Out the window I see cows standing amid the tulips on the median strip, with Mies's Seagram Building jutting up behind. They're fiberglass cows. One wears the broad stripes of some third-world flag. Another, the geometric lines of a Mondrian painting. My cabbie tilts his head toward the rearview mirror to catch my eye and says in a clipped Bombayan singsong, "I keep wondering what is the meaning of all these cows."

"It's art," I yell through the plastic safety shield.

"In my country, cows are for eating," he says, and it dawns on me that since cows are holy in India, he must be Pakistani.

Leaning up so I don't have to shout, I say, "Sometimes I wonder if people in this city even know where their hamburgers come from. Last Sunday I was at the Brooklyn Zoo pushing my one-year-old in a stroller, and this girl—she must have been twelve—looks right at a cow in the farm-animal pen and can't say what it is."

"A real cow?"

"A real cow. It was just a baby, but it was clearly a cow. Anyway, the girl's mother is getting frustrated. She keeps saying, 'Come on, you know what that is.' Meanwhile, my little boy's screaming 'moooo, moooo.' I couldn't believe it." I sink into the seat thinking not my kid, never and feel a rush of joy knowing just how true that is. Then I lean forward again. "I didn't stick around to see if she recognized the goat."

"In my country," he says, "goat is a favorite meat."

Just then another taxi swerves into our lane. "Hey!" my driver yells, slamming the brakes and banging the horn with the heel of his hand. The lurching and jerking stirs up the butterflies in my stomach.

At the intersection, we ease through a gauntlet of pedestrians, who stray into the street like ballplayers trying to steal a base. The ones hustling by on the sidewalks stare at their feet, mumbling and gesturing with their hands. Smokers huddle around the pillars of another corporate tower looking pathetic, all the glamour gone from their habit.

They all look terminal, the smokers and the non-smokers. The young, the old. The dapper and the bedraggled. All desperate, frenzied, bound for the grave, but too distracted to notice amid the crush of flesh passing through this landscape of concrete, glass, and steel. Until recently, I was one of them. Now I am leaving.

"My kid's going to know what a cow is," I declare, feeling compelled to share my news. "My wife and I are moving to a farm."

"You are a farmer?" he says, glancing doubtfully in the mirror.

"No. But I'm going to learn. I bet people still farm in your country. Regular people, I mean. To put food on the table." And then, getting more worked up, thinking about this man and his decision to leave his home country, "Don't you ever get sick of things here? Sick of the traffic, of living behind locked-and-latched doors, sick of the assholes? Jesus, you drive a cab. Your day must be one long parade of assholes."

The driver swerves to the curb and stops. He stares at me in the mirror. About to protest, I see Bryant Park and realize we have arrived. I pay, grab the receipt, and charge into the street before the changing light hurtles traffic at me.

I enter a marble lobby against the afternoon exit flow and ride the elevator alone to the seventeenth floor, where I step into the offices of National Geographic Adventure magazine. It is a new magazine, a how-to offshoot of the venerable gold-rimmed flagship. Adventure—the pasttime, the attitude—is hot. Stories about the frostbit heroics of Ernest Shackleton and tragedy atop Mt. Everest leap off bookstore shelves. Patagonia is no longer just a place; it is a fashion statement. When I first met with the editor during the hush-hush days of the magazine's infancy, the name was still a secret. "I bet you can guess it," he said with a sly grin. "It's a word you see everywhere these days."

Sure enough, I pegged it.

Growing up, I devoured adventure stories—Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, My Side of the Mountain, about a Manhattan boy who runs away to the Catskills to live in a hollow tree. I hunted Indian arrowheads, panned for gold with my father, stood by as Dad blasted copperheads with scatter shot from his .38 caliber pistol. The idea of escaping the confines of society in the wilds of nature appealed to a shy boy with a big imagination, even if society was a sleepy South Carolina mill town. When I graduated college, I boarded a plane for Kenya with a folder full of topo maps—bush schools circled in red—and directions to the home of two American teachers. I found a teaching job and stayed for a year, collecting rain water in a barrel, cooking over kerosene, and writing aerograms home by candlelight. When I returned to the States, I moved to Manhattan and worked as an editor for a start-up digest called The Southern Farmer's Almanac (I was a southerner, though I knew nothing about editing or farming). In what little free time I had, I struggled to publish freelance articles. Finally, a decade later, Adventure is sending me to places like Uganda and Ecuador.

Now, I sit in the magazine's conference room with a different adventure in mind, trying to find the words to explain my plans to the young editor across the table.

"James," I say, "did you know that two-thirds of the people in this country can't see the Milky Way?"

"No. . . ."

"Don't you find that depressing?"

"Yeah, I guess so," he says, frowning, "but what's this meeting all about? You've got me curious as hell."

I hesitate, peering around at the magazine covers tacked to the wall. Beautiful people in colorful outdoor gear pose in front of glaciers and waterfalls and half-moon bays. "I can't write the NGA Guide anymore."

Nodding his head, James leans back in his chair. "I know it's a lot of pain-in-the-ass research."

"It's not that." More nervous than I had expected, I pause. "I'm . . . taking myself out of the twenty-first century."

"What the hell does that mean?"

"It means I'm burned out. Heather and I are killing ourselves to keep up. We want to try something different—you know, while we're still young." I explain our plan—to live the life of dirt farmers from the era of our great-grandparents. We have a lot of details to work out, of course, but the basic premise is this: If it didn't exist in 1900, we will do without.

"And that means," I say, "we're not going to have e-mail, phone, computer, credit cards, utility bills, or car insurance."

"That's awesome!" James says. "Sounds like a real adventure."

Heather's supervisor, Meryl, a public-interest attorney raised in Queens, has a different take on the idea when, a week later, Heather breaks the news that she is quitting her job. "You," Meryl says, "are fucking crazy."

Maybe we are. Like everyone we know in New York, we work too much. Job stress follows us home at night, stalks us on weekends. Heather's work at a justice-reform think tank and mine hustling freelance magazine assignments keeps each of us either chained to PCs or traveling. Within the past two years, Heather has flown to every continent but Australia and Antarctica to interview cops and meet with government officials. When she was seven months pregnant, she gave a talk in Ireland, flew back to New York and left the same day for Argentina and an entirely different hemisphere. We figured that if she happened to give birth prematurely, it was a coin toss whether we'd have a summer or winter baby.

As it turned out, Luther was born more or less on time in Manhattan, in a hospital towering over the East River. By the tender age of four months, he was already in the care of a nanny, leaving us feeling guilty for having to hire her and also guilty about how little we could afford to pay her. (We felt guiltier still upon learning from another mother that our nanny was locking Luther in his stroller so she could gab at the park. We fired her and put Luther in daycare.)

We spend too much money on housing and not enough time outdoors. We order dinner from a revolving drawerful of ethnic take-out menus and rent disappointing movies from a corner shop where the owner hides behind bulletproof glass. There's something missing from our lives—from our relationship—and yet we're too busy to confront the problem. At least that's our excuse. So the two of us plod through our days hardly talking. And at night we collapse into bed, kept awake by the sound of squeaking bedsprings in the apartment above but too exhausted for any bed-squeaking ourselves.

It isn't a physical exhaustion. The beneficiaries of a multi-generational pursuit of the American dream, we have traded the farm and factory work of our small southern hometowns for education and urban living. Instead of a tractor accident or a limb lost in some mercilessly churning assembly line machine, we suffer the stress-related ills of our times: anxiety, depression, e-mail addiction, debt.

My tipping point came the day my beige plastic Dell tower—the tool of my trade—whined to a halt. The screen went black. With mounting panic, I punched the keys and poked the on/off button on the front. Nothing. Fingers followed the dusty power cord from wall socket to box. Plugged tight. My mind reeled at the thought of all that accumulated data trapped inside the wiry guts of a machine that I so little understood: pages of research, interview transcripts, an almost-finished article due three days earlier, book ideas, addresses, e-mail correspondence with friends and editors, family photos, business records, tax records. That computer was everything to me. And like a fool, I had not bothered to back it up.

Once I recovered from my initial panic, I thought back to my grandfather, a country doctor and cattle farmer. He was born in 1886, before all this so-called time-saving technology—cell phones that tie people to their jobs 24/7 and computers that keep them answering e-mails past midnight. Could someone whose tools were hand-shaped from iron, steel, and wood ever grasp the ethereal nature of lithium-ion-powered digital devices? This was my dad's dad—a mere generation stands between us—and yet he came of age in a world completely different from the one I know.

It dawned on me that no one yet knows the long-term side effects of Modern Life. Can we really adapt to all this brain-scorching change—the technological advances, the teeming cities, the breakneck pace of daily life, the disappearance of the human hand from the things we buy and the food we eat? Maybe my ambivalence about technology (and dread over my failed computer) was not something to be ashamed of. It was as if something in me shouted, Hold on a minute! You've been staring at the computer screen too long. When was the last time you dug in the dirt or tromped around a field, not to mention had anything at all to do with producing the food you eat? Maybe our disconnect with the natural world causes a sort of vertigo, and if so, maybe that explained my recent unhappiness. Or maybe I was just pissed off things weren't going my way. Whatever the reason, on that day I dreamed of escape.

And yet I dutifully called a Dell technician. With a wife and child, and a career to pursue, what choice did I have?

A few weeks later, I had a moment of clarity that in a flash changed everything. I was reading a newspaper story about an upcoming PBS show that pitted an English family against the rigors of 1900-era London life. Thinking back to my computer crisis and the question still ringing in my mind—what choice did I have?—I realized I had found my answer! Not the reality show itself, but rather its core concept—adopting the technology of the past. If I were so desperate for a change, why not travel backward in time as a way of starting over?

The year 1900 immediately felt right. I wanted to ditch certain technologies, but I did not want to be a pioneer, having to build a log cabin or dig a well by hand. The year 1900—almost within memory's reach—would serve well. A bit of research bore out my intuition. In 1900, rural dwellers still outnumbered urban dwellers. In 1900, agriculture was still the predominant occupation, thanks to millions of small-plot American farmers who raised most of what they ate for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In 1900, the motorized car—alternately called the viamote, mocle, mobe, or goalone—was still a novelty. In rural America, there were no televisions, telephones, or, of course, personal computers. People still wrote letters by hand. And this was crucial: In 1900, you could buy toilet paper.

I nervously told Heather my idea one Saturday as we juggled our fussy baby in a cramped Brooklyn pub. She smiled, and I remembered why I fell in love with her.

Four months later, we are heading south, crashing from pothole to pothole on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the Manhattan skyline jiggling in the rearview mirror of our beat-up Taurus station wagon. Heather rides shotgun. Luther squirms in back. Every other inch of space is stuffed with possessions. A moving van will bring the rest. My gaze drops from the World Trade Center Towers in the mirror to the mountains of gym totes and teddy-bear-filled Hefty bags threatening to avalanche Luther's car seat. The plastic clamshell luggage carrier that I bought the day before at a Sears auto store off Flatbush Avenue rattles the roof rack, and I muscle for a slot in the fast-moving traffic.

We're amped up and all singing together.

"Old McDonald had a farm. E-I-E-I-O. And on his farm he had a . . ."

"A REAL COW," I yell.

E-I-E-I-O.

Three days later, we are exploring Virginia, home of Thomas Jefferson, who wrote that "cultivators of the earth are the most virtuous and independent citizens." Though Heather and I are not farming yet, I haven't felt so independent in years.

West of Richmond, released from the Interstate, we whiz past farm-houses, mobile homes, and rundown full-service filling stations, the kinds of places that sell live crickets and pickled eggs in big, brine-filled jars.

"Look, Luther," I say, tapping my window toward animals grazing in a pasture. But he's more interested in the goldfish-shaped crackers in his fist. Soon we're turning off the state highway, easing the station wagon into a gravel parking lot beside a small house with a deck and a treeless yard. Flush with the profit we made from selling our Brooklyn apartment, we've arrived for our first real-estate appointment.

Excerpted from See You in a Hundred Years © Copyright 2012 by Logan Ward. Reprinted with permission by Delta. All rights reserved.

See You in a Hundred Years: One Young Family's Search for a Simpler Life

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Delta

- ISBN-10: 0385342683

- ISBN-13: 9780385342681