Excerpt

Excerpt

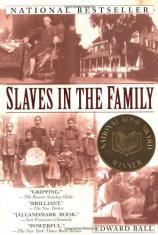

Slaves In The Family

Chapter One

Excerpt:

My father had a little joke that made light of our legacy as a family that had once owned slaves.

"There are five things we don't talk about in the Ball family," he would say. "Religion, sex, death, money, and the Negroes."

"What does that leave to talk about?" my mother asked once.

"That's another of the family secrets," Dad said, smiling.

My father, Theodore Porter Ball, came from the venerable city of Charleston, South Carolina, the son of an old plantation clan. The Ball family's plantations were among the oldest and longest standing in the American South, and there were more than twenty of them along the Cooper River, North of Charleston. Between 1698 and 1865, the 167 years the family was in the slave business, close to four thousand black people were born into slavery to the Balls or bought by them. The crop they raised was rice, whose color and standard gave it the name Carolina Gold. After the Civil War, some of the Ball places stayed in business as sharecrop farms with paid black labor until about 1900, when the rice market finally failed in the face of competition from Louisiana and Asia.

When I was twelve, Dad died and was buried near Charleston. Sometime during his last year, he brought together my brother, Theodore Jr., and me to give each of us a copy of the published history of the family. The book had a wordy title, Recollections of the Ball Family of South Carolina and the Comingtee Plantation. A distant cousin, long dead, had written the manuscript, and the book was printed in 1909 on rag paper, with a tan binding and green cloth boards. On the spine the words BALL FAMILY were embossed. The pages smelled like wet leaves.

"One day you'll want to know about all this," Dad said, waving his hand vaguely, his lips pursed. "Your ancestors." The tone of the old joke was replaced by some nervousness.

I know my father was proud of his heritage but at the same time, I suspect, had questions about it. The story of his slave-owning family, part of the weave of his childhood, was a mystery he could only partly decipher. With the gift of the book, Dad seemed to be saying that the plantations were a piece of unfinished business. In that moment, the story of the Ball clan was locked in the depths of my mind, to be pried loose one day.

When I was a child, Dad used to tell stories about our ancestors, the rice planters. I got a personal glimpse of the American revolution, because the Balls had played a role in it--some of us fought for the British, some for independence. the Civil War seemed more real since Dad's grandfather and three great-uncles fought for the Confederacy. From time to time in his stories, Dad mentioned the people our family used to own. They were usually just "the slaves," sometimes "the Ball slaves," a puff of black smoke on the wrinkled horizon of the past. Dad evidently didn't know much about them, and I imagine he didn't want to know.

"Did I ever tell you about Wambaw Elias Ball?" he might say. "His plantation was on Wambaw Creek. He had about a hundred and fifty slaves, and he was a mean fella."

My father had a voice honed by cigarettes, an antique Charleston accent, and I liked to hear him use the old names.

"Wambaw Elias was a Tory," Dad began. "I mean, he picked the wrong side in the Revolution." When the Revolutionary War reached the South, Wambaw Elias, instead of joining the American rebels, went to the British commander in Charleston, Lord Cornwallis, who gave him a company of men and the rank of colonel. Wambaw Elias fought the patriots and burned their houses until such time as the British lost and his victims called for revenge. The Americans went for Wambaw Elias's human property, dragging off some fifty slaves from Wambaw plantation, while other black workers managed to escape into the woods. Wambaw Elias knew he had no future in the United States and decided to cash in his assets. Eventually he captured the slaves who had run away, sold them, then took his family to England, where he lived for another thirty-eight years, regretting to the last that he had been forced to give up the life of a slave owner.

In the Ball family, the tale of Wambaw Elias and his slaves passed as a children's story.

Use of this excerpt from Slaves In The Family by Edward Ball may be made only for purposes of promoting the book, with no changes, editing or additions whatsoever, and must be accompanied by the following copyright notice: copyright (c)2001 by Edward Ball. All Rights Reserved.

Slaves In The Family

- paperback: 505 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345431057

- ISBN-13: 9780345431059