Excerpt

Excerpt

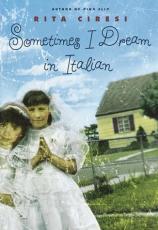

Sometimes I Dream in Italian

Big Heart

He came out of the back, his apron bloody. The butcher Mr. Ribalta had the biggest belly I had ever seen. When he leaned into the case to grab a handful of hamburger or lop off a rope of sausage, his stomach grazed the meat. I wanted to poke his fat, to see if my finger would sink into it like pizza dough, or press my ear against him, to hear his insides sloshing and grumbling. But I hung back from the meat counter until he crooked a plump finger and beckoned me forward.

"Oh, Swiss Girl," he called. "Yo-do-lo-do-lo-do-lay."

I always eyed his Swiss cheese. I wanted to take a chunk of it home and slip it between a wedge of sharp pepperoni and a slice of salty prosciutto on a seeded roll. But Mama refused to buy it. "I don't pay good money for holes," she said. She frowned when Ribalta reached into the case to cut me a sliver.

People said Ribalta had a big heart, but Mama was convinced his heart longed for only one thing: to turn her into a big spender. Every Saturday morning before we left the house for the market, she armed herself with a black plastic wallet stamped with a picture of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, a shopping list, and a green pencil stub she had pocketed after playing miniature golf at Palisades Park. Since my sister, Lina, thought she was too old for such outings, Mama took me--a mere nine-year-old who didn't yet know how to protest--as a witness. I was supposed to make sure Ribalta didn't try any monkey business, like doubling the wax paper or pressing his thumb down on the scale. Although Mama had patronized Ribalta for years, she still didn't trust him. "It's not like he's family," she said.

The market stood on a corner, the front windows lined with white paper, lettered in blue, that announced the weekly specials. Above the shop, behind windows hung with yellowed lace curtains, Ribalta lived with his mother. Mama called her Signora. For years I thought that was her first name.

In cold weather or warm, Mama and I found Signora out front, sweeping the dirt and litter off the sidewalk with a ragged broom that had lost half its dirty bristles. Signora reminded me of La Befana, the skinny old Italian witch who rode her broom over the rooftops on the Feast of the Three Kings, leaving toys for good children and coal and ash for the bad. She wore a black cotton coat over a flowered shift and scuffed gray mules with no stockings. Her brittle ankles and calves were mapped with thin blue veins. Signora was practically bald, but what little tufts of gray hair she had left on her pink scalp she clamped around wire curlers fastened with big silver clips. She held her broom still just long enough to peer at us through her cat glasses. When she was satisfied she had recognized us, she resumed sweeping.

Ribalta's shop officially opened at nine, but we always walked in a little after eight-thirty. Brass bells clattered as the door swung behind us. Mama headed down the first narrow aisle, stopping once or twice to inspect some canned goods that sat on the high wooden shelves. "Cheaper at the A&P," she announced loudly.

At the back of the store stood the gleaming white meat case, lit with fluorescent tubes that made the unit hum and vibrate. Behind the case was a swinging door and, behind that, the mysterious room where Ribalta butchered his meat while Radio Italia played. Mama went up to the counter and hit the silver bell on top with the flat of her hand. The radio went dead. We heard water running. Then Ribalta came out of the back, his breath heavy as he wiped his hands on a clean white cloth. He pushed his gold wire-rimmed glasses up on his nose. He was the only shopkeeper in our neighborhood who ever smiled at Mama.

Mama nodded back, her eyes on the case. Ribalta stocked it so the contents ranged from the reddest and rawest meat to the cleanest, tidiest rolls of processed food. First came the organs--bloody bulbs of liver, tough-looking necks, and limp hearts--packaged in clear plastic containers. Then came ground beef pressed in an aluminum tray, rump roast and flank steaks, coils of sausage, and a quilt of overlapping bacon strips. Cuts of pale pork and veal were followed by moist chicken breasts and piles of stippled yellow legs and scrawny wings. In a separate section of the case, Ribalta kept logs of prosciutto, mortadella, Genoa salami, and blocks of cheese.

Mama checked each item on her list against Ribalta's prices. Then she placed the list on top of her wallet and firmly crossed off some items with the pencil stub. "Here's what's left," she said. It always took Ribalta a long time to fill the order. Mama made him display each cut of meat, back and front, before she allowed him to put it on the scale. And when she said she wanted half a pound of something, she meant eight ounces, no more and no less. Ribalta knew better than to ask Mama if a little bit over was okay. He patiently lifted chop after chop onto the scale, while Mama watched the gauge waggle back and forth until it settled as close to the weight she had asked for as it would ever get.

After Ribalta had wrapped the meats in stiff white paper, tied each bundle with red and white string, and marked the price with a black wax pencil, he crossed his arms and rested them on his big belly. He knew exactly what Mama was going to ask for next.

"Any scraps today?" she said.

"For the dog, eh?" Ribalta held up one finger, meaning Mama should wait. He disappeared into the back.

I never understood why Mama kept up this charade. We didn't have a dog and never would. "Good for nothing except to bite and bark," Mama said, whenever I pleaded for one.

"If you hate dogs so much, why do you tell Ribalta we have one?" I asked.

"I tell him no such thing."

"But you let him think we do."

"I can't help the ideas he gets in his head," Mama said.

She waited impatiently for Ribalta to return with the scraps. He came back balancing a pile of metal pans. He displayed the contents to Mama and the haggling began.

"Veal bones," he said. "With plenty of meat. Chicken necks, close to ten of them."

Mama rejected the necks and offered fifteen cents for a bag of bones.

"Make it a quarter," Ribalta said.

"For those sticks?"

"These are beautiful bones. Juicy. Tender. Flavorful."

"Twenty cents," Mama firmly said.

Ribalta never said done, fine, or okay. He simply moved on to his next offering. "Giblets. Fresh this morning. And these hearts, I saved them just for you."

They went back and forth like that, until Ribalta ran out of scraps and Mama was satisfied she had bled him for whatever she could get. Ribalta stacked the white packages in a box. Then he winked at Mama and peered over the case at me.

Courtesy of Random House, Inc.

Excerpted from Sometimes I Dream in Italian © Copyright 2012 by Rita Ciresi. Reprinted with permission by Random House. All rights reserved.

Sometimes I Dream in Italian

- hardcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: Delacorte Press

- ISBN-10: 0385334931

- ISBN-13: 9780385334938