Excerpt

Excerpt

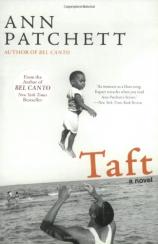

Taft: A Novel

Chapter One

A girl walked into the bar. I was hunched over, trying to open a box of Dewar's without my knife. I'd bent the blade the day before prying loose an old metal ice cube tray that had frozen solid to the side of the freezer. The box was sealed up tight with strapping tape. She waited there quietly, not asking for anything, not leaning on the bar. She held her purse with two hands and stood still. I could see her sort of upside down from where I was. She was on the small side, pale and average-looking, with a big puffy winter jacket on over her dress. I watched her look around at the stuff up on the walls, black-and-white pictures of Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf in cracked frames, a knocked-off street sign from Elvis Presley Boulevard, the mounted head of a skinny deer. She pretended to be interested in things so she didn't have to look at anybody. Not that there was much of anybody to look at. It was February, Wednesday, four in the afternoon. The dead time of the deadest season, which is why I wasn't in any rush. The tape was making me crazy.

Before I even got the box open, Cyndi walked out of the kitchen and headed right for her. "What can I get you?" Cyndi said. Then I straightened up because the girl in the puffy coat wasn't, of a drinking age. She was eighteen, nineteen. Could've been younger. When you'd spent as much of your life in a bar as I had, you recognized those things right away. Cyndi, she knew nothing about bars other than getting drunk in them. She was just a girl herself, and girls were no judge of girls.

"Get her a Coke," I said, and headed over to them. But the girl put up her hand and I stopped walking just like that. It was a funny thing.

"I'm here about a job," she said.

Well, then I could see it. The way she was overdressed. The way she didn't seem to be meeting anybody but didn't seem like she was there to pick anybody up either. We got plenty of girls through there. We got the college girls looking to make money to pay the bills who wound up trying to read their books by the little light next to the cash register when things were slow, and then we got the other kind, older ones who liked the music and liked to pour themselves shots behind the bar. Those were the ones who walked out in the middle of their shift with some strange customer on a Friday night when the place was packed and then showed up three days later, asking could they have their job back. Those were the ones the regulars always took to.

"You over at the college?" I said, and Cyndi looked at her hard because she didn't like the college girls.

The girl nodded. A piece of her straight hair slipped out from behind her ear and she tucked it back into place.

"How old are you?" I said.

"Twenty," she said, so quickly that I figured she'd practiced saying it in front of a mirror. Twenty. Twenty. Twenty. She didn't look twenty, but I would bet money that her ID was fake. It didn't so much matter in Tennessee. Seventeen could serve a drink as long as they kept it clear of their mouths.

"Any restaurant experience?" I looked at her hard, trying to tell her age from her face. "Ever work in a bar?" I was out of those employment forms. I made a mental note to order a box.

She nodded again. Quiet girl. "Not around here, though. I'm not from around here."

Cyndi and I stood there on the other side of the bar, waiting for her to say where she was from but she didn't. "Where?" Cyndi said.

"East," the girl said, even though that could mean anywhere from Nashville to China. East was the world if you went with it far enough. I didn't think she was trying to be difficult on purpose. The way she stood so straight and kept her voice low and respectful, it was plain that she needed the job. I liked her, though I didn't have a reason. Even when I just saw her standing there, when she put up her hand and for a second it felt like something personal. I liked this girl.

"What's your name?" I asked.

"Fay Taft," she said.

"Like the president?"

"What?"

"William Howard Taft."

"Oh, no," she said. "My father tried to trace that back once, but he didn't come up with anything. I don't think our Tafts ever met their Tafts."

"Only president ever to be chief justice on the Supreme Court." I had no idea why I knew this. Some facts stick with you for no reason.

"He was fat," she said in a sorry voice, like there could be nothing sadder than fat. "I always felt kind of bad for him."

Not very many people who come into bars can talk to you about dead presidents. I told her she had a job.

Cyndi turned on her heel as soon as I'd said it. Cyndi wanted two shifts a day, seven days a week. She wanted every tip from every table in the place. She saw no need in the world for a waitress other than herself.

"Come back tomorrow," I told Fay, not looking over my shoulder at Cyndi, who she was straining to see. "Come in before lunch. We'll get you started."

She wasn't saying a word. She looked too scared to take a deep breath.

"That okay?" I asked.

"School," she said softly, like the very word would be the end of it. No bar, no job.

"So come after class. Just be here before happy hour. That starts at five. Things get busy then.''

She smiled, her face wide open with relief. For a second that little white face reminded me of Marion, even though Marion's black. This was Marion from way back, when I could read every thought that passed through her like it was typed up on her forehead. Young Fay Taft nodded, made like she might say something and then didn't. She just stood there.

"Okay, then?''

"Okay,'' she said, nodded again, and headed out the door. I watched her through the window as she went down the sidewalk. She took a stocking cap out of her pocket and pulled it down over her ears. The cap was striped blue and yellow and had one of those fluffy pom- pom things on the top. In it she looked so young I thought I must have made a mistake. One thing's for sure, she never would have gotten a job wearing that hat. It was gray outside and spitting a little bit of snow that wouldn't amount to anything. The girl, Fay, stopped at the corner and looked out carefully at the traffic, trying to decide when to cross. I watched too, watched until she crossed and headed up the hill and I lost sight of her skinny legs trailing out of that big jacket.

"Like we need another waitress,'' Cyndi called down loudly from the end of the bar.

But Cyndi hadn't been around long enough. She didn't understand about the spring, how waitresses take off for the gulf on the first warm day and leave you with nobody trained. Best to stock a few girls up when it's still cold outside, ones who look reliable enough to last you past seventy degrees.

"I'll tend to my job and you tend to yours,'' I said, going back to the Dewar's. Cyndi had a hell of a mouth on her. Maybe that's the way they teach girls over in Hawaii where she came from. "I'm the one that hires people.''

Cyndi took up a couple of clean glasses and went back to the kitchen to wash them again, just to let me know it wasn't right.

If it was or it wasn't, I had no one to account to. It was my job. I hired people and got the boxes of scotch open. I counted up the money at two o'clock in the morning and took it to the night deposit box, every night waiting to see if somebody was hopped up enough to crack me over the head for it. I plunged the toilets when they backed up. I used to throw people out when they got drunk and started beating one another with the pool cues, but then that got to be a full-time job so I hired a bouncer, a former Memphis State linebacker named Wallace whose knees had gone bad. He worked the door on Friday and Saturday because no matter how drunk people got on a weeknight they just about never took to beating on one another. This is one of the great mysteries of the world. I was putting Wallace on behind the bar more and more during the week. He made a good mixed drink. The tourists liked him because he was coal black and huge and the sight of him scared them and thrilled them. When he wasn't busy doing his job he was posing for pictures with strangers. One tourist snaps the camera while the other tourist stands next to Wallace. It tickled them to no end to have their picture taken with someone they thought looked so dangerous.

The bar I managed is called Muddy's and is on the water side of Beale down past the Orpheum Theater. It's owned by a doctor in town who holds more deeds in Memphis than anyone knows. He bought it back in the late seventies from Guy Chalfont, a bluesman we all admired. Chalfont swore the bar wasn't named for Muddy Waters or the Mississippi River, but for his dog, a filthy short-haired cur called Muddy that followed him with the kind of devotion that only a dog could muster. It seemed like all the old bluesboys sold out in the late seventies with some sad notion about going to Florida. They thought it would be better to die down there, sitting on lounge chairs near the ocean, wearing sunglasses and big Panama hats. They sold just before the real estate market broke open, a couple of years before their little clubs turned out to be worth a fortune.

The main thing I had to do to keep the job was book the bands and make sure they showed up and didn't plug all their amps into the same socket. In the winter it wasn't so hard because it was pretty much a local thing, the same people playing up and down the street on different nights. But the truth was that good blues were nearly impossible to find. Real music had packed off to Florida with the old boys. I had about decided the problem was that people didn't suffer the way they used to. I was an advocate of greater suffering for anyone who came through my club. Bands these days were always hoping to be what they called crossovers, which meant that white college kids would start buying their records, thinking they'd really tapped into something. People watered themselves down before they even got started. They thought if their blues were too blue there'd be nobody to buy them since nobody, they figured, was interested in being that sad.

When I took this job everybody said I'd be the right man for it. I was a musician so I'd know, run the kind of club a musician would like to be in. But when I started managing I stopped playing. I forgot what all of that was about and people around town forgot I ever was a drummer. I was running a club just like everybody else who was running a club. I was the guy who passed out the money at the end of the night.

I took the job managing Muddy's at a time when things with Marion had come all the way around, from her doing everything to please me to me doing everything to please her. I said I'd stop playing and take on a regular job to show how steady I could be. I thought it was just for a while, like you always think something bad is for just a while. I figured I'd get her settled down and then I could go back to the band. I didn't take into account that I might lose my nerve, all those nights in a bar when I was watching instead of the one up there playing. I didn't imagine how that could undermine a person. Once you thought about a beat instead of playing it you were as good as dead. Nothing came naturally anymore. I could play at home when I was by myself, but as soon as somebody else was there my hands started to sweat. Then I just ditched it altogether. After Marion and Franklin were gone, long past any hope I had of them coming home, I kept my regular job as manager. It was all I knew how to do.

When Marion took our boy to Miami last year she stopped calling him Franklin and started calling him Lin, like she was in a hurry and there was no time to say his whole name. Sometimes she called him Linny, like Lenny. It was her way of saying I didn't know him anymore, that anything that had come before was no good, even his name. Sometimes I called him Frank, but Marion didn't like that one bit. If I called down there and asked to speak to Frank she'd act like she didn't know who I was talking about. No Frank here, she'd say, and make like she was going to hang up.

That was when I'd want to tell her that Lin was a pretty name for a daughter but I'd called to talk to my son. I never said that. Marion had been known to hang up on me and when I called back she didn't answer. She had a million ways of keeping me from him that had nothing to do with me and Franklin and everything to do with me and her. Marion was pissed off at me for winding up how I did, which is to say, winding up like myself.

When I pressed too hard for visits or a school year back in Memphis, she'd say that maybe Franklin isn't my son. Nowhere on paper did it say he was mine, since she was mad at me the day she delivered and left the father slot on the birth certificate blank, like maybe so many people had been down that road there was just no way of knowing. Franklin was my son. Marion was eighteen when he was born and for all her tough talk nine years later, I knew who she was then. Her face was wide open. Marion used to wait around for me while I was playing. She'd smile at me and turn her eyes away and laugh when I looked at her for too long. She wasn't screwing around and I wasn't screwing around. We were good to each other back then.

She liked me because I played drums in a band. One of the many reasons she didn't like me later on. I wasn't a centerpiece, no Max Roach, no showy genius like Buddy Rich, but I was as solid a drummer as you were going to find and everybody wanted me. I made the other people look good. That's what a good drummer does. He keeps everybody steady and paced. He shines his light at just the right time. That was me.

I was born drumming. My parents admit to that even though they were never happy about it. I was asking to hold two spoons from the time I knew how to hold one. I heard beats in everything, not just music, but traffic and barking dogs and my mother washing dishes. I heard it. That was who I was, big arms and loose wrists. Getting a set of drums just made things easier. Getting a band made them easier still. Twelve years old, I was sitting in with a bunch of high school boys. I knew, right from the start.

The band I was in when I took up with Marion was called Break Neck, now one hundred percent scattered. We played mostly in Handy Park and when we couldn't get in there we played down by the water until the cops ran us off. It was all hat passing then, decent money if you were on your own but a joke once you carved it up in six directions. By the time we were getting real jobs with real covers, we were already falling apart, changing out the bass player one week, going through three singers in a year. I left before the whole thing evaporated. I got another band and then another one. As soon as I could outplay them I was gone.

If I had to narrow myself down to one mistake I've made in my life, it would be that I didn't marry Marion as soon as I found out she was pregnant. She was eighteen and I was twenty-five. She was still pretty much under the impression that I had hung the moon. She'd gone down to the drugstore and bought herself one of those kits that tell you yes or no. You didn't have to wait around very long, not like the old days of girls going down to the doctor's office. Back then when the test came back yes, everybody would go around saying the rabbit died. But someone told me a long time later that all the rabbits died. Killing them was how they did the test. I imagine a lot of rabbit farmers went out of business when the at-home tests came on the scene.

Marion didn't say one word to me about it before she knew for sure. She was brave like that. There are a lot of things you have to give Marion credit for. When she told me, she was happy. Her face was always very pretty when she was happy. She has a high forehead that slopes back. She has big eyes and wide, flat cheeks, and a mouth that always looked like it was about a second from telling you everything but it didn't have to since it was all right there. We were sitting on the back steps of her parents' house, splitting a Coke because there was only one left. She was wearing cutoffs and a yellow halter top and she looked as good as any girl I'd ever seen. She hadn't gotten all dressed up or taken me away some place secret to tell me. There was nothing to be ashamed about. Marion's face didn't have a worry on it. It said, I love you and you love me and all of this is going to be fine.

And that was the thing that made me turn on her.

It wasn't the news itself. It was something about the way she looked at me, like she knew I would never disappoint her, that made me want to disappoint her badly. This is called being stupid and cruel. This is being twenty-five and a drummer in a band when there are plenty of pretty girls who aren't pregnant asking for your time. I had been faithful to Marion because she was right, I loved her. But I didn't need her. It was her need of me that made me turn cruel.

So what would have happened if I had acted like the people on television? Picked her up and kissed her. Set her down in an old lawn chair all nervous and put a pillow up under her feet. What if I had rested the side of my face against the yellow halter top that barely covered her stomach and just held it there for a minute. Where would we be now? Marion and I keep no secret store of love for each other, I will promise you that. Everything that was kind between us we killed with years of dedication and hard work. When I hang up the phone with her now it's hard to imagine that one tender word has ever passed between us. I find myself thinking that we must have been drunk or stoned during any minute we were happy together.

She tried to stay close to me when she was pregnant. She didn't know what else to do. I guess she wanted to be there in case I wised up. Some days I was good to her and some days I wasn't. I picked up a few other girls on the side. I started taking myself seriously, talking big. I gave her money, but I made her ask for it. I never said one word about marrying her. She was my own fat shadow, getting bigger and bigger as she trailed along behind me. Every time I made her crazy and she wanted to light into me, she bit down hard and kept quiet about it. She was trying to hold on to her old sweet self. Marion had a clear idea about what kind of girl she wanted to be, no trouble, not one who complained no matter how badly she was treated. I can see her clear as day, coming to the bar in the hot late afternoons while the new band practiced. She'd sit at a table drinking ice water with her legs stretched over two chairs. She never looked like she was listening, never said anything about the music one way or the other. She was just making the effort to put herself in front of me. She had to leave her parents' cool house after working all day and ride a crowded bus downtown, not to talk to me or be with me, but just to sit in front of me in an empty bar so I wouldn't forget she was going to have my baby.

Franklin came sooner than anyone thought he would. I was playing at the Rum Boogie. When the manager told me at break that it was Marion on the phone I didn't take the call. She didn't tell him she was having the baby and I didn't think of it, a whole month early. Later, it came out that she was standing at a pay phone in the hospital lobby, having contractions and waiting on the line because no one went back to tell her I wasn't coming. She stood there listening, waiting for me to pick up until her legs just gave out on her. That pretty much explains my name not being featured on the birth certificate.

A visit to the nursery may not be Paul's road to Damascus: I was a bad man before I saw and a good man after, but it's something like that. Children get right to the point. I've known solid men to take off straight away in the face of their sons. I've known men you'd think were bad, hustlers and junkies, who smoothed over, found something in themselves that turned them decent because now they have a baby to look after.

How did this work? When Marion, a good girl, came to me and said she was going to have my child, I said I'd call her when there was time. But when my boy Franklin came I was so crazy for him I wanted to marry her a million times over just to keep them close to me. And the second I told her so, everything changed. Now I wanted her. She could relax, collect herself and take a look around. It was then that Marion had the luxury of discovering just how completely she hated me.

Marion Woodmoore took our son and went to live with her parents after she left the hospital. Right away I began my campaign that they should come live with me. Her parents didn't want that, no surprise.

"Can't believe you're even standing in my living room,'' her mother said to me. "I'm going to have to vacuum for an hour just to get your smell off the carpet.''

Her father stood in front of the couch with his arms crossed to make sure I didn't try to get comfortable.

"Let me talk to him a minute,'' Marion said to them, calling off the dogs.

"We'll be right in the kitchen if you need anything,'' her father said, looking at me but talking to her.

"Don't let him hold that baby,'' her mother said.

Once they were gone I told her to come live with me.

"Hah!'' I heard from the kitchen.

"My parents hate you,'' Marion said. She put her little finger in the baby's mouth and let him suck on it.

"Make up your own mind,'' I said to her. "You're a grown woman now. You've got your own family, me and Franklin. Families ought to be together.''

"So you'd think,'' Marion said. She looked at the door to make sure no one was watching. "You can hold him for a minute.'' She handed me the tight bundle of my son, not even heavy enough to be a good-sized ham.

I was holding Franklin, who was named for her father, who was named for Roosevelt, his father's all-time favorite president. I told everyone I knew that I had named him for Aretha. "See that,'' I said, chugging him gently up and down.

"What?'' Marion pulled back the blanket to look at the baby.

"See how he's looking right at me?'' I said.

Marion relented and moved in with me when Franklin was six months old. Her parents stood at the door and cried. He was a good baby by any standard; none of that colic, laughing all the time. He only cried to let you know what he needed, a bottle or a nap. I liked to take him out with me. I liked for strangers to come up and say what a good-looking boy I had. I'd take him to the bars when I could do it without Marion finding out. All the waitresses would leave their tables and the cooks came out of the kitchen. Everyone in this town has known me forever. I wanted them to know my boy.

I tried my best to make things work with Marion, to make her settle down and stay. But no matter what kind of flowers I brought home or how many times I told her I was sorry, she couldn't let things go. She moved out just before Franklin turned two, and she took him with her. It was like she couldn't stand the sight of me. Every day I was nice to her she turned on me a little more.

"That day you were playing at Raymond's,'' she said as soon as I walked in the door. Three in the morning and I'd been playing since nine that night. I was nearly too tired to sleep.

"Don't,'' I said.

"I was sitting there at the table with you, seven months along, and here comes that girl. She sat on your lap. On top of you! She wasn't that big around.'' She made a circle between her thumb and forefinger to show me. "You didn't even push her off. You didn't ask her to sit in a chair.''

I slid down the doorframe and sat on the floor. That's how tired I was. I didn't want to get any closer to her. "I was wrong,'' I told her. "My head wasn't in the right place back then.''

"I should have put your head in the right place,'' Marion said quietly. She was tearing up a paper towel in tiny bits, which is what she did when she was mad. Newspapers, napkins, Kleenex, the mail, Marion shredded them like a pack of hamsters.

"Baby,'' I said from way over on the other side of the room. "Why don't you and me get married? That would make all this better. Franklin needs to have married parents. Then we'll be a real family. We'll get married and put the past in the past. What do you say about that?''

But she didn't say, because by then she was crying. Marion didn't like to cry in front of people. She scooped up all the paper shreds and took them into the bedroom with her and shut the door.

Six months after she moved out she came back again, saying she decided what she wanted was to go to nursing school and she figured I owed her that. Marion had been working as the cleaning girl at a Catholic school because the hours were right, but anyone could see she was a million times too smart for that and it was bound to make her crazy. The nuns were always getting on her about how she dusted the statues, had she wiped behind their feet? Cleaned their heads? Marion said the glass eyes on the Virgin Mary chilled her. I was all for seeing her go back to school, especially if it meant them coming home. Franklin was all over the place at that age, talking in sentences, picking up everything so fast I thought he must be way above average. I wanted to see him every day, not just on the weekends. I thought if they moved back we might be able to work things out, the three of us.

"I'm talking about lots of school here. I need to take classes just so I can start taking classes. That means time and money. Regular money,'' Marion said. "You're going to have to find yourself a salary job.''

"Band's doing fine,'' I said, though I knew good and well what she was talking about.

"One good night, one good week, that's not going to cut it.'' We were sitting at a table at Muddy's at the time, having a couple of beers. She was twenty-one years old, but she was so steeled up inside nobody would have believed that. She still looked pretty, not the same kind of pretty she was when I met her, but maybe better. She wore her hair brushed back in a tight knot now instead of fixed up and she didn't bother with makeup. The fact that she didn't smile that much anymore made her look kind of mysterious. She was sexy now, even when I knew that sex, at least where I was concerned, was about the furthest thing from her mind. She was sexy in that way that pretty women who couldn't care less can be sexy.

"So if I get a regular job, you and Franklin'll come back?''

"You help me pay for school, take care of Franklin when I'm studying,'' she said, and took a sip off her beer. All cards out on the table, that was Marion.

I put my hands flat against my thighs. Whatever it was, it wasn't going to be forever. I was a drummer. That was all I'd ever been. Now I was a drummer and Franklin's father. I didn't see how those two things could cancel one another out.

Marion looked at her watch. "I told Mama I'd be home to help with supper,'' she said, and finished off the beer. "You let me know.''

"I'll let you know now,'' I said. "You and Franklin come on home. I'll get a regular job.''

"We'll come back when you've got the job,'' she said.

I walked up to the bar as soon as she was out the door and talked to a fellow named Danny King, long since disappeared from Memphis. I asked him, Did he know what was out there, what had he heard? The next thing I knew I had a job at Muddy's, first booking the music and running the floor at night, then six months later the manager quits to buy a dance club and I had the whole place to myself. Easy as falling down.

Of course, it wasn't what Marion had in mind. She wanted to see me out checking phone wires for South Central Bell or selling Subarus. Jobs that took place in the light of day. But she didn't press it too hard. She knew it was the first regular job I'd had in my life and that these things took some time.

Marion went to school during the day while I watched Franklin and then she came home and took him in time for me to go to work. We didn't sleep much and we didn't much sleep together. I'd get into bed at four and she'd never so much as roll over. By the time I woke up, she was gone.

All that time we lived together she never forgave me anything and I got plenty sick of asking her. There was a long time when I would have gone along, married her, everything, had she been able to drop the subject of my bad behavior for one minute. Then even that opportunity passed. I'd see her studying at the kitchen table and just walk right by, not even thinking about her being a breathing person in the room. I couldn't picture her at eighteen the way I used to. That was a trick I had, a way of making myself feel warmly towards her.

"Hey,'' she said, and shook my shoulder. "Wake up and quiz me.''

"Quiz you?'' The room was dark and sweet smelling. I remembered for a second that Marion wore perfume called Ombre Rose.

"Here, take the book.'' She clicked on the light and it hit me square in the face. I pushed up on one elbow. "I've been studying all night,'' she said. "I know it. I just need somebody to quiz me.''

I rolled away from her and pulled a pillow over my head. "Quiz yourself.''

"I'm serious,'' she said.

"Don't you think I'm serious?''

What time I had in the day I gave to Franklin, who deserved it. He was a ball of fire, getting into things, tearing things apart. I often thought that if I were capable of so much movement I would have been the greatest drummer that ever lived. He liked to play something I called the Name Game, which was going up to everything and identifying it, right or wrong. Potato. Chair. Wall. Door. Daddy. Table. Tree. It was a long time before I could look at anything without stopping to think about what it was called.

When Marion graduated from Memphis State I took Franklin to see her get her diploma. We sat with the Woodmoores, who had softened on me since I'd sent their daughter through nursing school. I held Franklin up on my lap and pointed her out and he said "Mommy,'' but she was too far away to hear. Then the three of us went home and I waited. Waited while she took her boards and found a good job at Baptist. Waited while she got three paychecks stored up in the bank. She thought I'd be so surprised when she came home saying she'd found an apartment for the two of them closer to the hospital and she'd be out by the weekend, but I'd been watching it heading towards me for years.

What surprised me though, what made me want to wring her neck once and for all, came later when she announced they were moving to Miami for no good reason.

"Better jobs down there,'' she said.

"You need a better job than what you have?''

"Go back in your room for a minute,'' she said to Franklin. "Find your blue scarf. I can't find that scarf.''

Franklin went back slowly, wanting to hear what we were saying since it was him that we were fighting over. He was eight years old by then, which I found impossible, so stretched and thin you would think he was never fed. He was still too young for any sort of trouble that counted, but I knew he was moving into that time when boys needed fathers around, someone to keep them in line. Marion had done a good job with him, no one was going to argue that, but it wasn't the time to be taking off.

"Miami's too rough,'' I said.

"Memphis is plenty rough.'' She was getting ready to go in for her shift. She was wearing her white uniform. Her little white cap was sitting on the table by the front door, wrapped in a plastic bag. The white always made her look fresh, like she'd had a good night's sleep. Just putting on that dress kept Marion young.

"You got a boyfriend? Somebody you know going to Miami. Is that it?''

"I wish that was it,'' she said in a nasty way, as if to tell me I'd spoiled that for her, too.

Franklin reappeared, the blue scarf hanging straight down over one shoulder like a flag. "Bingo,'' he said.

"We're going to talk about this some more,'' I told his mother, and held the door open for Franklin to go on ahead of me.

"Don't worry yourself,'' she said. "This isn't going to happen tomorrow.''

But it happened, sooner than I would have thought. We had our share of fights over it, but they always came down to Marion saying my name did not appear on the birth certificate. For all those years I'd done nothing to see that Franklin was legally mine and she could take him out of the state just for the pleasure of doing it. Other times she was kinder. She said her parents were here and sure, they'd be back plenty. I could take Franklin on vacation in the summer and come down to see him if I gave her some notice. She said it wasn't like they were falling off the face of the earth.

I never did get the real reason she was going, but I could imagine Marion just wanted to give something else a try. There she was, a few years shy of thirty and what had happened except she'd had a baby way too young and spent her whole adult life mad at a man for not being good to her when he should have been. The year before there was a nurses' convention in Chicago. The head nurse got sick at the last minute and they sent Marion in her place. That was the first time she'd been on a plane. She'd taken things as far as they were ever going to go in Memphis. If something better was going to come to her, then she'd have to be willing to leave.

It wasn't like I was so used to coming home to my son at night, but when they left for Florida I found I didn't want to be in my apartment anymore. I didn't much want to be anywhere, so I stayed at work. I built new storage shelves for the kitchen so that the extra flour and canned tomatoes could be unpacked and put away. There had always been boxes all over the place. After that the whole kitchen seemed bigger. I reorganized the bar next, and once I started I could tell it should have been done years ago. I put the things you poured the most right up front, instead of it being alphabetical, the crazy way it was before, with Amaretto and applejack being the things you always wound up grabbing. I even started listening to the demo tapes that people sent in, something that nobody in their right mind would do. I got to where I would know in the first ten seconds whether a band was going to be any good. Most of the time you could tell by how they'd written their name on the box. Most of them were so bad it made me wonder how they could have thought it was a good idea to spend the money for blank tape. Finally, I found a little blues band called Tenement House from New Orleans, a town I am suspicious of musically since they were the ones that came up with that Dixie crap. I told them they could come and play, and it turned out they were good enough to keep all week. They were popular here and everybody talked about how I'd found them, how I had the ear. I wanted to say no, it was nothing as complicated as that.

I told everybody that I was working so much because I needed the money, or I told them I stayed at work because I didn't have the money to be going out. Money was the other thing. I told them Marion was soaking me. Any man will give another man sympathy for that. When Marion went to Miami she decided she'd need to have a set amount every month, an amount that she figured up to cover things. I won't say how much. It makes me uncomfortable to talk about money and it always has. Up until Miami we never had a problem with this. I gave her what she needed. I took Franklin out for clothes and in the fall we went to Woolworth's for school supplies. I bought him binders and pencils and other things, things he maybe didn't need but just wanted, like twelve-packs of Magic Markers that smelled like different kinds of fruit. I liked it this way. I got to spend my money on him. It never seemed like too much. If someone came around to the bar telling me they knew a good deal on hams, I'd go out and buy one for Marion. I never went to her place in the summer without peaches or a basket of sugar beets. I wrote out the checks for the visits to the dentist. I bought shoes, which aren't cheap and get tossed aside six months later when they're outgrown. I saw that they had plenty. I took good care. Franklin always knew who was looking out for him. But in Miami I couldn't take him shopping. Marion wanted X dollars on the first of every month, or the fifteenth if that was better, but the same money at the same time like clockwork. I didn't want any part of it.

"He's your son,'' she said.

"Funny how that works. Sometimes you think he is and sometimes you're not so sure.''

But I knew Marion. She could find her way without my money and without me, so I paid. I worried about that payment all the time. I was always checking to make sure I had enough to cover it. When I put it in the envelope I'd write a note to go along. This is for half the electric bill, for class trips, for a new pair of jeans. Something along those lines.

When I got home from work the day I hired the girl in the puffy jacket and the striped stocking cap, it was nearly three in the morning. I'd stayed open late because there were a couple of guys still drinking at the bar and I figured there was no point in throwing them out. I was in no hurry. Two minutes after I walked in the door the phone started to ring. I could only think it was bad news. When it was Marion on the other end and she was crying, I knew it as fact.

"Franklin,'' I said to her. "Tell me.''

She took a breath. "He's okay.''

"Marion, why are you crying? Settle down, tell me what you're crying about.''

"He fell,'' she said, then started up again. "Where were you till three o'clock? I've been trying all night.''

"He fell how?'' I said. There was no spit in my mouth and I sat down on the edge of the bed, which I hadn't made once since Marion left.

"Where were you?''

"Work,'' I said, trying not to be short with her. She wouldn't call me at the bar. Not if a life depended on it. "Fell how?''

"At the beach. He was running with some boys. They pushed him or he fell, I don't know. He fell on some glass, a piece of Coke bottle he says. It cut his face. The side of his face.'' She was crying. "It was by his eye, but it didn't cut his eye.''

I looked at the carpet, a bad orange and brown shag left over from the seventies. I should have found a day job, something regular, found a nicer place to live. "Where is he now?'' I said, thinking maybe in the hospital.

"Right here, asleep. He's fine now. It just scared me to death is all. Then you weren't home. When I got the call I thought he was dead at first.''

"Stop that.''

"Everything's fine, but I thought---I didn't want to call my parents. I didn't know who to call.''

"You call me,'' I said. Was there a bandage around his head? Was it only taped up over the cut? Did the white from the tape make his skin look warm and rested up the way his mother's uniform made her look?

"Don't fight me about this,'' she said, tired.

"Who were the boys? Who was he with?''

"Boys from around here. There're boys everywhere. He has friends from school. They play.''

"Are they rough kids? Do you know them?'' I wanted to blame her, but only because I felt too far away. I wanted to go into his room and see him sleep. Miami was drugs and guns and gangs, packs of half-starved refugees who'd kill a boy like mine for the sneakers he was wearing.

"Some of them,'' she said, "but there's no sense in wondering. It's nobody's fault, unless it's my fault.''

"You shouldn't have taken him so far away,'' I said.

"I need some sleep,'' she said. "I have to work tomorrow.''

I started to ask her if she'd heard me, but she hung up.

I sat there with the phone in my hands, not able to put it down in case I thought of another question. I didn't know what things were coming to, how things had gotten so far away from me. This wasn't terrible. A cut near the eye was not a lost eye. I lay back on the bed and closed my eyes, touching the side of my face where I imagined the cut would be. I hadn't asked her if it was on the left side or the right. I saw my son's head. It was oval-shaped. His hair was as short as it could be and still be hair, but it wasn't shaved off on the sides and the back. There were no lines shaved into this boy's head, no thin braid at the nape of his neck. His skin was darker than mine or Marion's. It was not an inky black, a blue black. It was a warm color, brown black. His eyes were lighter than his skin. I thought about the shape of his eyes. I thought about his mouth, which was wide and bright. I thought of every tooth that mouth contained, every one of them straight and hard and white as chalk the way new teeth are. The phone began to make that awful sound phones make when they're off the hook and no one is at the other end. It startled me, and then I hung it up.

I thought about Franklin's face so hard I gave myself a headache. I wanted to know what happened. I wanted to know all of it. I pictured the day hot, even for this time of year in Miami. From a distance I could make out some shapes and then make out that they were boys. They were coming from every direction. The boys gathered up together like some sort of dust storm moving down the street. Haitian boys, West Indian boys, lighter Latino boys with black silky hair. They wear red tank tops, T-shirts that say Batman or Desert Storm. They are barefoot, in tennis shoes and flip-flops as they run down the street laughing. Boys picking up boys like dogs packing together. Then all of a sudden Franklin is with them. He's not wearing a shirt. He's wearing some shorts that are so big they cover his knees. They are electric blue. He is hollering with the boys and I can't hear what he's saying. They're on their way to the beach, which isn't far. They cut through the traffic, not waiting for anything, cut across the parking lot, weaving in and out between the cars, trying to hide and scare one another. They make their way down to the sand and across the sand to the water. They run back and forth with the waves, trying to keep their feet dry, acting crazy. One boy gets in the water and pretends to drown. He cries for help in a foot of water and the pack goes in to save him, but he struggles because everybody knows a drowning man will fight off the person who is trying to save him. Franklin reaches down to him, but when he does the drowning boy slings out his arm and catches Franklin hard on the side of the face. Franklin, hit, falls back into the water. Now the game changes without anyone saying anything about it. It is to drown someone instead of to pretend you're drowning. All at once they reach out to catch Franklin's arms and pull him under. Franklin gets the change in the program just as fast as they do. There are so many boys, eight counting Franklin, and they get all tangled up together. One boy pushes him under by the neck and he shuts his eyes tight against the salt water. The water fills up his nose and ears and blocks out the sound of the voices. Franklin is terrified, scared like an animal. He kicks up out of the water with everything he's got and his foot makes contact with something and for a second he is let go. He takes that second to make his break. In the water he is slick and he slips between them. He digs his heels in the wet sand and takes off running, twice as fast as before, and the boys run after, screaming. He's pretty far away, past the empty lifeguard chair, halfway to the parking lot, when he takes a look behind him for one quick second, loses his balance, and goes straight down into the hot, soft sand. The broken bottom of a 7UP bottle, a flat disk of green glass with a quarter inch of jagged edge, cuts a half circle on the side of his face near his left eye. When he raises his face out of the sand he doesn't know he's bleeding. The sight of the blood stops the wild boys dead and turns them all back into regular boys again. Just like that. They forget that things had gotten out of hand or that Franklin is the one they were chasing, and Franklin forgets too, as soon as he touches his hand to his face because there is something, not water, dripping into his eye.

I had such a wave of sickness come over me that I thought I was going to throw up, but by the time I walked into the bathroom it had calmed some and I poured myself a glass of water from the tap and went back to the bed. Four in the morning. I held my eyes open to keep from seeing the part where he was falling.

Then for no reason at all I thought of that girl Fay. I didn't know where she lived. I didn't have her phone number so I could call her and tell her that she couldn't have the job, if I was to decide not to give it to her. I couldn't call to find out if she was okay if I was to go in tomorrow and not find her. It wasn't that I wanted to think about her, but by seeing her face I could make myself not see Franklin's, so I thought about her. I could barely fix her in my mind, the thin skin on her temples, the red that the cold put on her cheeks. I couldn't remember the color of her eyes or if her straight hair that wasn't blond or brown was cut into bangs the way so many girls her age like to wear their hair these days. I wondered where in the east she came from. I wondered who was looking out for her. Who made her that ugly hat. I remembered how careful she was when it came time for her to cross the street and it made me feel comforted. Someone taught her what to watch for. But then, they didn't teach her well enough if she was wandering down to Beale looking for work in bars. There was no watching them every minute, Marion. We can't be everywhere. What are you going to do but teach them to look?

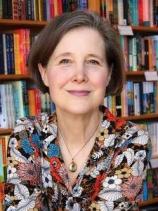

Use of this excerpt from Taft by Ann Patchett may be made only for purposes of promoting the book, with no changes, editing or additions whatsoever, and must be accompanied by the following copyright notice: copyright ©1998 by Ann Patchett. All Rights Reserved.

Excerpted from Taft © Copyright 2012 by Ann Patchett. Reprinted with permission by Ballantine. All rights reserved.

Taft: A Novel

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060540761

- ISBN-13: 9780060540760