Excerpt

Excerpt

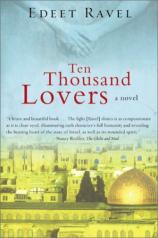

Ten Thousand Lovers: A Novel

Chapter One

A long time ago, when I was twenty, I was involved with a man who was an interrogator.

I met him on a Friday morning while hitchhiking from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. I was studying at the university in Jerusalem but I always spent weekends in Tel Aviv because Jerusalem shut down at weekends and there was nowhere to go and nothing to do. Tel Aviv, on the other hand, was at its liveliest on Friday nights and Saturdays. That was the weekend: Friday night and all day Saturday. Sunday was an ordinary working day, and I had to be back for an early class.

I was hitchhiking from the soldiers' hitchhiking booth, and I was embarrassed. The booth was supposed to be for soldiers only; a student with waist-length blond hair and wearing a short skirt would always get picked up before the soldiers did and they resented it. But that was the only place you could hitchhike from, because right after the booth the road began winding wildly around the dark green mountains of Jerusalem.

Usually I took a shared taxi to Tel Aviv on Fridays. The shared taxis were seven-passenger Mercedes sedans and were fairly comfortable if you had a window seat. But I was short on cash that morning. My roommate, a Russian immigrant, had asked me for a loan, and I had just enough left to get me through the weekend, so I walked to the booth, stationed myself as far from the soldiers as possible, stretched out my arm and pointed at the road with my index finger. Hitchhiking in Israel isn't deductive. It's not about letting the driver know what you need (which is what an upturned thumb would indicate) but about telling the driver what to do (which is what a finger pointing to the road indicates).

The soldiers began to mutter and grumble. I tried not to listen to them. I wanted to be liked.

A car stopped almost immediately, pulled up next to me. Three pissed-off soldiers left the booth and walked defiantly toward us.

"Tel Aviv?" I said.

The man in the car said, "Tel Aviv."

"You're sure?" I asked. Because the last time I'd hitchhiked, the driver lied about where he was going and left me stranded in the middle of nowhere.

"Ya-allah, what a paranoid. Hurry, get in before they kill us."

Behind us the soldiers were cursing. "Kusemak," they said.

"Let them in," I said, getting into the front seat.

"Well, unlock the back door."

I pulled up the lock and the three soldiers, two men and a woman, slid in gloomily. They all needed to get off at different places. One was headed for Petah Tikvah, one for Shfayim, and one for Hadera. They were still pissed off, but they couldn't really say anything now that they had what they wanted. Ya-allah is Arabic, of course. Ya is an Arabic particle, similar in usage to "O" in English (as in, "O Pyramus" or "O wall"). Placed in front of a name in everyday speech (e.g., ya-Asaf) it's emphatic and means something like "Yes, you, my friend, I'm talking to you."

You wouldn't think ya-allah would be a favored phrase among Israelis, but it is.You use it the way you'd use the expletory "God" or "Christ" in English.

Kusemak is Arabic too. There aren't a lot of swear words in Hebrew because for 1800 years Hebrew wasn't really a spoken language. When Hebrew was (artificially) revived, some swear words had to be borrowed. Kusemak means "cunt of your mother" in Arabic, but it isn't used as an insult in Hebrew: it's just used to express annoyance. In Arabic you wouldn't use that phrase lightly, but in Hebrew it's no big deal, because native Hebrew speakers don't really think about what it means.

- - -

The man said, "Ami," and I said, "Lily," and we shook hands sideways and said, "Pleased to meet you," or, literally, "very pleasant," which is what you say when you shake hands in Israel; you can't shake hands without saying na'im (pleasant) me'od (very). Everyone in Israel shook hands when I was there, even young people, even very cool young people. It was cool to shake hands (with a grim look on your face, though) when you met someone. I wonder whether it's still like that today.

It was a little awkward shaking hands in the car, and I could feel the contempt of the soldiers in the back, thinking they were watching a pick-up.

But Ami didn't say much after that. He only asked me whether I was in a rush, because he wanted to drive the soldiers as close as possible to their final destinations, which meant a lot of detours. I didn't mind. I liked going on drives, especially in expensive cars with bucket seats.

He dropped off the soldiers one by one: one at her home in Petah Tikvah, one at his home in Shfayim and the third at the turn-off to Hadera. The soldiers were no longer angry; they were grateful to be taken right to their door or to a convenient intersection. They thanked Ami enthusiastically and one even placed his hand on Ami's shoulder before he got out.

After the soldiers had gone, Ami said, "Student?"

"Yes."

"What are you studying?"

"Literature. Linguistics."

"Chomsky?"

"Yes, he's hot now."

"Our good friend Noam."

"Uh-huh."

"You're Canadian."

"How did you know?" Usually I was taken for an American.

"I'm good at accents."

"Canadians have the same accent as Americans."

"Not exactly."

"I don't believe you. You just guessed."

He laughed. "OK," he said.

"What do you do?" I asked him ...

Excerpted from Ten Thousand Lovers © Copyright 2003 by Edeet Ravel. Reprinted with permission by Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

Ten Thousand Lovers: A Novel

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060565624

- ISBN-13: 9780060565626