Excerpt

Excerpt

Terrorists in Love

1

AHMAD’S TRIP TO HEAVEN AND BACK

CNN LED the news on Christmas Day 2004:

On the heels of a visit to Iraq by U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, a fuel truck driven by a suicide bomber exploded Friday in western Baghdad….

At least eight people were killed and 20 others wounded by the explosion…. Fifteen people, including women and children, were in critical condition, and many had suffered severe burns, hospital officials said….

Baghdad police said they were looking for another fuel truck in the area and a BMW that they believe is associated with the attack.

My inside story of the suicide bomber responsible for this attack actually began in Washington, D.C. Through contacts in the media and a senior American intelligence official, in the spring of 2008 I met one of the top officials of the Saudi Arabian government responsible for counterterrorism. The high-ranking Saudi Ministry of Interior official became my friend. It helped that he was looking to buy a condo in D.C. and his son wanted to attend an American graduate school—both areas where I guided him through foreign shoals. The favor was returned inside the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

But my unprecedented access inside Saudi Arabia was not only the result of a personal trust between me and the Saudi official; I also benefited from timing—and luck. From 2008 through 2010, the Saudi Ministry of Interior decided to open its jihadi prison rehabilitation program to a few select outsiders. The Ministry of Interior is the most powerful government agency in Saudi Arabia, responsible for counterterrorism and internal security.

Saudi Arabia, in many ways, is the country most important to the future of Islam. Home of the faith’s holiest places, it is the world’s richest kingdom, with a quarter of the earth’s oil reserves and wealth highly concentrated in the royal family and few others. Saudi Arabia is also the home of a strict, fundamentalist interpretation of Islam founded by Muhammad al-Wahhab, which is the source of Al Qaeda’s ideology. Saudi citizens continue to be the principal financial supporters of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, and other radical Islamist groups. However, since 2003, when Al Qaeda began attacks inside the country, the government has led an official campaign against the radicals, or jihadis, as they call themselves. Still, Saudi Arabia is one of the most closed societies in the world, largely inscrutable to outsiders.

As president of the nonprofit research institute Terror Free Tomorrow, I interviewed more than a hundred terrorists and Muslim radicals throughout the world to understand what motivates them. In Saudi Arabia, over many months, I had the unique opportunity to interview at length forty-three Saudi jihadi militants who had fought inside Iraq and Afghanistan. I conducted the kind of in-depth, one-on-one interrogations that were a part of my professional background as a federal prosecutor and congressional investigator. Some people’s accounts were not credible. Other radicals’ activities offered little in the way of implications for future policy, while many were not insightful or self-aware. Yet, by persevering, I came to uncover a world “behind the veil.”

My interviews in Saudi Arabia began during the summer of 2008. In a convoy of Ministry of Interior (MOI) black GMC Yukons, with as much security as afforded the vice president of the United States in Washington, D.C., we sped to the euphemistically named “Care Center”—the special Saudi prison for rehabilitating jihadi militants. When I say sped, I mean it literally. We reached speeds of 100 mph or more on Riyadh’s American-designed superhighways, which reminded me of “the 10” approaching Santa Monica, only without the Pacific on the horizon.

As we left modern Riyadh, the Saudi capital of nearly five million (which also reminded me of Century City with its isolated gleaming skyscrapers surrounded by neighborhoods of strip malls), I looked out at the bright brown terrain in search of Arabian life in the patches of desert that were now cropping up. Instead, I saw all manner of ATVs and 4×4s spewing exhaust and dust, with people camping next to their Land Rovers, open flames, and barbecue grills, and the ubiquitous ice cream vans that continually trolled the sands.

We sped through the “resort” northeast of Riyadh, Al Thumama, with its dusty amusement parks, finally passing Al Fantazi Land on the right. It’s Riyadh’s great amusement park, a Disneyland, my MOI driver said, where Islam reigned.

While I was staring at Fantasy Land, the latest-model Yukon, which still had the factory plastic shrink wrap over its leather seats, took a sudden, jarring right off the highway. Past the run-down Lebanese Fruits Restaurant, over dirt roads and sand-colored, walled-off homes, we pulled up to an unmarked security gate.

The guard waved us in before we drove through another gate, stopping at a grassy dead end and finally a sign: MINISTRY OF INTERIOR, DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC RELATIONS, THE CARE CENTER. For two years, this would be my “home from home,” as the prison warden, MOI Major General Yousef Mansour, told me. The Care Center prison for reforming jihadi terrorists offered psychological counseling, antidepressant medication, religious re-education, art therapy, vocational training, water sports—some dubbed it the “Betty Ford Jihadi Clinic.” (I had mentioned to my high-ranking MOI friend the fact that the prison was part of the ministry’s “Department of Public Relations” might give Americans the wrong message, and I noticed on subsequent visits that the center was renamed and the original sign had been changed to remove “Public Relations.”)

Of the forty-three jihadi inmates (“beneficiaries”) I interviewed, Ahmad al-Shayea, nicknamed “Bernie,” had to be the most striking, his entire body bearing the scars of the first suicide bomber in Iraq who had survived his attack. His face was covered with red pustules. His nose curved to a strange hooked point, like a ski jump. The fingers on his right hand ended in a stump that resembled melted candle wax, while his left-hand fingers were twisted like the roots of a miswak stick jihadis regularly chew in imitation of the Prophet Muhammad (and that tastes exactly like the bitter herbs from a Passover Seder). His fingernails were little more than yellowed brown stumps, the color of toes infected with athlete’s foot.

Sitting in the prison faux-tented reception area, or majlis, with the air-conditioning going full throttle, I was accompanied by MOI Lieutenant Majid, my favorite interpreter, who spoke in 1980s American slang (he’d grown up in Orlando, Florida), and “Dr. Ali,” Ahmad’s prison psychologist, a phenomenal host, with whom I shared many long dinners and who had received his doctorate in psychology from the University of Edinburgh. We were also accompanied by the usual retinue of Pakistani and Bangladeshi servants, with the endless small cups of gahwa (Arabian green coffee), highly sweetened black tea, and sticky dates. The occasional MOI security guards never had the patience to sit through more than thirty minutes at a time of our six-to-eight-hour-long interview sessions.

Ahmad was shy and modest. It took much prompting from me, Lieutenant Majid, and most of all Dr. Ali, who would prod Ahmad with what they had discussed in their therapy sessions. As is fitting for a student of both Sigmund Freud and the Holy Qur’an, Dr. Ali helped Ahmad begin his singular life story as a failed suicide bomber with a dream—even if a dream from Abu Ghraib.

BURNED BEYOND RECOGNITION, his skin charred and dark, Ahmad al-Shayea could dream of only one thing: dates. Not the light tan Sukkary dates his family had once so proudly grown in the center of Saudi Arabia—“the best dates in all Buraydah,” his grandfather always bragged. Ahmad couldn’t stop dreaming of the rival dates from the distant eastern province of Saudi Arabia: the bitter, black Khlas dates that Grandfather scorned.

The Holy Qur’an told Ahmad that as a martyred fighter in the way of jihad, he would be eternally nourished in Paradise by “date palms.” Yet instead of the sweetest Sukkary that Grandfather said would be the food of Heaven, his veins were hooked to salty water. Instead of wearing “robes of silk” and reclining on “jeweled couches,” as the Holy Book pledged, Ahmad lay on a stiff white bed. Missing too were “the dark-eyed, full-breasted virgins, chaste as pearls” offered by Allah the Most High to any martyr. He hadn’t reunited with his family as promised either—his younger brother, cherished grandfather, beloved mother. He was alone.

Ahmad had been “thrown into the fire of Hell,” as the Holy Qur’an warned all sinners. He’d come to Iraq to fight the Americans on Noble Jihad. But his suicide mission had ended instead at Abu Ghraib.

And all Ahmad could dream of was the darkest Khlas dates.

FOOD HAD ALWAYS foretold the fate of Ahmad al-Shayea’s family, as far back as anyone could remember. More than two centuries before, with literally no food to eat because of unending drought, the family had left Ha’il in the north to go to Buraydah, an oasis capital of Al Qassim in the heart of Arabia.

Then it was all about the dates.

The family became date farmers and traders, growing mostly Sukkary, unique to Al Qassim. From Buraydah, the “Date Capital of Saudi Arabia,” they cultivated some of the best Sukkary, the most sought-after dates in Arabia, particularly prized during Ramadan. And for Ahmad’s grandfather Abdurrahman al-Shayea, his Sukkary had no equal in sweetness of taste, smoothness of yellow meat and amber skin.

The “International City of Dates” gave them enough wealth that Grandfather could even open a small grocery store. The Abdurrahman al-Shayea Store featured the endless variety of sweetness Grandfather proudly grew and traded.

Riding the back of Saudi Arabia’s first oil boom instead, Ahmad’s father, Abdullah, left the world of dates far behind. With oil revenues exploding into royal government coffers, the Saudi civil service grew in tandem, becoming the largest employer in the country. Abdullah profited and, like so many others, obtained a comfortable position in the government. Starting in police administration, he rose to the middle level of health care administration for Buraydah, which has a reputation as one of the most conservative cities in the entire Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

While shunning Grandfather’s dates, Abdullah kept faith with tradition in other respects and submitted to an arranged marriage with a second cousin. Tribal custom provided that sons marry a relative, chosen by his family. The couple had two girls and three boys, with Mother staying at home, following tradition, of course.

For tradition meant everything in Buraydah. And as Buraydah is at the center of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Arabia is at the heart of the Muslim world. The birthplace of Islam and custodian of its two most holy places, it is also the home country of Osama bin Laden and fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers. Buraydah and its surrounding area kept faith, giving the world most of the Saudi fighters inside Iraq—including Ahmad al-Shayea.

BORN IN 1984, Ahmad was the oldest son. He attended the nearby government Ibn Daqeeq al-Eid Elementary School, where half the classes were in religious subjects. The Holy Qur’an was his favorite class—even though his father never recited from the Book. By the time Ahmad was old enough to attend Prince Sultan Middle School, he was still small and frail at only five foot two. He didn’t like to talk in class or enjoy the rough ways of Saudi soccer. He had no friends and spent his free time in front of the screen—TV or computer. That’s when his father would start to yell: “Why don’t you do your homework, play some soccer, something, instead of wasting away at home like a girl?”

Ahmad hated his father’s shouting. Like the hot dust wind from the desert, you never knew when it would strike.

“Leave the boy alone, Abu Ahmad,” his mother always said to her husband, addressing him with the honorific title “Father of Ahmad.”

Umm Ahmad was his beloved mother, who always called herself by her kunya, the honored “Mother of Ahmad.” Allah Almighty had given her the greatest blessing of a first son. She loved him “more than life itself.” While the religious imams of Buraydah cried when reciting the Glorious Qur’an, Umm Ahmad cried while holding her favorite child.

“There’s only one God, and there’s only one Ahmad,” she’d say.

Mother Ahmad always took Ahmad’s side no matter what, which only further provoked his father. Indeed, Abu Ahmad almost seemed to be competing for his wife’s affection with his first son. And Abu Ahmad had nothing if not a fierce temper—the only limit to which was his fear of lapsing into “a diabetic fit.”

If it got too bad, Ahmad would flee to Grandfather’s old-world store. The oil boom had transformed even Buraydah into a rebuilt modern city with American-style roads and strip malls of gas stations, furniture and convenience stores. But Grandfather’s traditional grocery and date store on 80th Street in the Prince Mishal district felt like a relic from a former age.

Grandfather always made Ahmad feel at home, kissing him warmly on both cheeks, embracing him with his old smell of sandalwood oil and incense smoke. Ahmad supposed that if his grandfather had a computer or even a TV, he would move right into Grandfather’s “land of dates”: Sefri, Khudairi, Suqaey, Safawy, Shalaby, Anbarah, Ajwah, Helwah, Madjool, Rothanah, Maktoomi, Naboot Seif, Rabiah, Barhi, Rashodiah, Sullaj, Hulayyah, Khlas, and most of all, of course, Sukkary.

Ahmad could name them all. Some boys could recite the Holy Qur’an, yet he could recite all the distinct variety of dates and explain how each had its own unique color, taste, texture. And while he couldn’t recite Qur’anic chapters, he could point out each of the twenty-nine times dates were named in the Holy Book. Reciting their Qur’anic attributes, Ahmad and his grandfather savored every date. And Grandfather’s shot was the stuff of legend: spitting each pit through his missing middle front teeth into a large brass bowl, which had been passed down in the Al Shayea family for generations.

But sweet dates weren’t Grandfather Al Shayea’s only love. Grandfather’s other secret passion was Arabic love songs, most of all, those of “the Noble Lady,” Umm Kalsoum, the legendary “Star of the East.” The great Egyptian contralto continually sang in the background on the old record player. Grandfather loved all her songs but perhaps most of all “Lissah Fakir”: “Do you still remember all that was in the past?” Ahmad’s favorite was the classic “El Atlaal,” especially one version that lasted more than an hour: “Give me my freedom, untie my hands!”

With the grand lady of Arabic song wailing of unrequited love, the old man and the boy mouthed a date at exactly the same time, eating its yellow flesh at the same speed, in rhythm with the Star of the East’s syncopated beats and whirling trills. They’d finish together and, as Umm Kalsoum moaned or cried at the end of a verse, would spit out the date pits like soccer balls into their goal. This was a sport Ahmad excelled in, even though Grandfather enjoyed the advantage of missing his front teeth.

The singing of their recorded “mother” egged them on and became a vital part of the “date game.” As Umm Kalsoum tackled a particularly high note, the date pits would launch together. Sometimes Ahmad felt that the clapping on the old records was not for Mother Kalsoum but for Grandfather and Ahmad, as the pits hit their spot. Score! The people clapped! Umm Kalsoum trilled her deep voice again as only she could! The pits would launch once more. Some people claim that the Noble Lady sparked tarab—ecstasy—in her listeners. Ahmad didn’t know about that. But Mother Kalsoum had certainly provoked the firing of many a Sukkary pit from the lips of Grandfather and Grandson al-Shayea.

Grandfather only played his cherished Umm Kalsoum records in private with Ahmad. When Saudi television and radio stopped broadcasting Umm Kalsoum after the 1979 attack on the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Grandfather didn’t understand why. How Umm Kalsoum could be considered un-Islamic when her father was an imam, descended from the Prophet himself, and when she even sang verses from the Holy Qur’an, eluded Grandfather. But to be safe from the mutaween (religious police), the date game, with Umm Kalsoum providing the musical sound track, became Grandfather and Ahmad’s secret from the world.

By the time Ahmad turned sixteen, he was only five foot six and still thin as a date pit. He looked more like a twelve-year-old boy than a man. But he now felt Mother Kalsoum’s lyrics from “Inta Omri” growing inside him too:

“I started to worry that my life would run away from me.”

His family went to mosque on Fridays, observed Ramadan and Eid, but his father never prayed five times a day. Instead, he complained about getting diabetes, and though he avoided dates like desert locusts, he still constantly drank cloyingly sweet tea, even ate baklava and all kinds of honeyed pastries. Ahmad’s father, who said you should be observant but didn’t make the holy pilgrimage, and who extolled the Book but would smoke his hubbly-bubbly in private when no one was looking—never even listened to the Noble Lady.

IT WAS THE first Eid celebration after 9/11. It was also the first time since Ahmad was little that the entire family went to dinner at a restaurant. The Jerusalem Restaurant, one of the oldest in Buraydah, was the only place Grandfather would eat out since it bought his very own Sukkary dates.

The Eid dinner at the Jerusalem Restaurant was a feast with Lebanese food the family was not used to. The family ate separately, with the women apart. Unlike many families in conservative Buraydah, Ahmad’s family always ate as one at home, the men and women together.

Ahmad couldn’t remember eating separated like this before. But he was sixteen and couldn’t be his “mother’s pet” for the rest of his life.

At the end of the meal, when the overly sweet pistachio baklava came, Ahmad went to stand alone on the sidewalk outside. The desert night air was cool. Perhaps he should turn toward religion, he thought. He had never truly known God. Under his breath, Ahmad was busy mouthing the words of a prayer to himself, moving his hands up and down in the air, like an imam at mosque giving a sermon.

Ahmad was so engrossed in his daydreams that he didn’t notice his father leaving the restaurant. He came from behind and, startling Ahmad, began to mock him, waving his hands wildly in the air.

Father Ahmad always made sure his head was meticulously covered with the customary red-checkered shemagh headdress. Continually taunting his son to “crawl out from under Mama’s abaya,” he had even threatened Mother Ahmad that if she didn’t leave the boy alone, he would take a second wife. But Grandfather didn’t approve of having more than one wife, so Father Ahmad showed him the “tribal honor” that was due any father—why couldn’t his own son show the same? All he wanted was for his eldest to “wear the white”—become a man.

Ahmad turned toward him and blushed like a boy. He felt humiliated to see his father mocking him.

“Stop,” he cried. There was no sin worse than to talk back to your father. It could send you to Hell. Hell, the religious teachers told him, where fire seventy times hotter than the earth’s would burn off his skin only to grow back and be roasted off again; where he’d carry his intestines in his hands, chains binding him while he hung from his boiling feet, bitten by scorpions the size of donkeys and snakes as big as camels, and his dry, cracking desert mouth would beg for the only drink ever offered: his own pus and blood that never stopped flowing.

No sooner had the word “Stop” left his cursed lips than he regretted it and his father’s open hand slapped Ahmad’s left cheek.

As Ahmad then raised his arm to stop another blow, it hit his father’s hand, which enraged his father even more.

Ahmad saw his father’s brown eyes turn black with hate. “How can a little mama’s boy strike me?” he yelled, balling his fist in full fury.

Ahmad fell back and instinctively spat, as if a date pit were leaving his mouth at full speed, as if an evil jinn were caught inside his throat. It wasn’t as if he were trying to spit at his father, God forbid, but he tasted pus and blood.

His father hit him again before Mother Ahmad came between them, as she always did.

“Abu Ahmad,” she cried, deliberately addressing her husband by his kunya. “He was just talking to himself. Where’s the sin in that?”

“Out of the way, Umm Ahmad.” His father wasn’t finished, his face now red as pressed date paste.

“By the Word of God, you’ll have to strike me first before you hit him again,” she said. She didn’t flinch.

Mother Ahmad was imposing in her own right. She too loved food and was the reason the family never ate out. A wonderful cook, her jareesh was the sweetest in Buraydah. She was equally strong in or out of the kitchen. She was the love that held the family together.

“Damn you both,” Father Ahmad muttered.

“Jafar,” she now said firmly, using the secret name only she called him. “You keep this up, and you’ll send yourself into a diabetic fit.”

At that the father dropped his fists to his side and loosened his fingers. The wife’s plea for his survival worked better than a mother’s plea for her son.

Or perhaps it was that Grandfather had finally left the restaurant. Ahmad felt sure if Grandfather had been outside with them, his father never would have struck.

That night, his mother came to kiss him good night, as she always did. She brought his glass of hot milk to help him sleep and repeated her customary bedtime greeting: “How’s my favorite son I love more than life itself, the very best son in the whole wide world?” He did not reply, as he always did in turn, “He kisses the hands of the very best mother in the whole wide world.”

Instead, after his mother shut the door behind her, he couldn’t stop crying. It was the first time he remembered crying like that in years. Maybe because he saw a tear in his mother’s eye before he rudely just told her good night. Maybe because Grandfather never saw what happened or said anything to come to his rescue outside the Jerusalem Restaurant—Jerusalem, where the Prophet Muhammad ascended to Heaven. Because of his father’s eyes, Ahmad was headed to Hell: he saw the black hate inside them, and nothing was the same again.

THE NEXT DAY, Ahmad dropped out of school. His father refused to get angry. “You’re not worth a diabetic attack,” he said.

Ahmad wanted a friend. He had none in school. He’d used to hang with his cousin all the time when they were little in primary school. Even some in Prince Sultan Middle School, until they fell out of touch in secondary school. Adel was everything Ahmad was not. Tall, with dark eyes and wavy black hair, he even had the beginnings of a manly beard sprouting on his face. Adel played soccer and drove his very own “love car”: a neon-red Chevy Camaro with tiger gold stripes. He even smoked when no one was looking. There was nothing awkward or shy about him. What would he want with puny Ahmad?

Ahmad was so nervous when he first tried to call, he dialed the wrong number.

“Adel? It’s Ahmad, Cousin.”

Adel was more than a year older and had just turned eighteen.

“Hey, Cousin.”

Ahmad’s fears melted away.

“Long time no hear, Cousin.” Adel peppered his speech with “cool” American slang.

“I dropped out of school today and figured you’d help me celebrate.”

“Cool. I’ll pick you up, Cousin. Long as your old man doesn’t see me.”

“Fuck him.” Ahmad thought of “El Atlaal”: “Give me my freedom, untie my hands.”

Adel laughed. He was the one who seemed nervous now, but came to pick Ahmad up in his blazing red Camaro. Everybody saw the classic. It was a head turner, the hottest car in Buraydah or even its twin city, Unayzah. It had everything: a carbon-fiber hood scoop, signature turbocharger, custom hypersilver wheels, and of course those gold tiger racing stripes.

As Adel almost “burned rubber” speeding the Camaro away from Ahmad’s house, he raised his right hand to give him a high five American style. Ahmad slapped his hand like an American too and never felt so happy in his whole life.

From that day, they hung together nonstop. More, Adel brought him into his “posse.” With a core of six boys, the posse sometimes grew to eight, even nine.

They raced the classic Camaro against another gang’s souped-up Mustang. Adel was one of the best at drag racing. More than drag racing: tafheet, or “drifting,” where Adel would spin out and skid the Camaro sideways, down the parking lots and deserted side streets of Buraydah and Unayzah in the middle of the night. The gang also went to the Al Nafud desert outside Buraydah, racing 4×4s over the rocky, steep dunes and sand hills. Camping in the desert, the boys tormented the poor dhub lizards around them, never bothering to cook them over an open flame in true Bedouin tradition. They were not about tradition.

With so many boys, there sometimes was a free house to hang at when the parents were at mosque. But the gang usually went to estirahas, small houses outside town, where they could play video games, watch TV, smoke cigarettes. “Hot cars, cool friends, and free air,” they said.

Soon the posse started to score hashish. Getting high on hash helped pass the time. Getting high made Ahmad better at the video games and surfing the Internet, something new and cool.

“To kick it with girls” was the posse’s main drive, or so they’d say.

The boys would roam the streets and “spy girls.” They’d follow the girls who shopped in groups. And if the girls had no adult man with them, it’d be open season for “spying”: asking them to take a ride in the hot Chevy, come back to the estiraha, and hang out. They asked if the girls found them sexy. They’d even ask for a quick peek behind the veil. The boys would also “spy” from the street, driving in the Chevy or in Mohsin’s Impreza. Of course, a girl riding with another Arab man would be off limits. Only if a Pakistani, Filipino, or Bengali servant were driving would the boys feel free to spy.

But nothing ever happened. The boys were all talk, and the girls, while sometimes giggling, never ended up meeting a single boy. The game of spying seemed more important than a real girlfriend or the arranged marriages that tradition would eventually grant them.

Ahmad passed the next year like this and hardly slept at home. Every time he did, his father would repeat the same litany. He’d begin by yelling, you’re supposed to be the eldest son, but what kind of role model are you? Then, still red, he’d yell how Ahmad was not even worth a diabetic fit, while his mother always sided with Ahmad, telling her husband that he was the one driving Ahmad away. It ended with his mother in tears and Ahmad fleeing with Adel and the posse: scoring hash, drag racing the Camaro or drifting the Impreza, spying girls.

UNTIL THE DAY Adel came back to the guys boasting of his conquest.

“My-ree-ah, oh, My-ree-ah,” Adel said. “I did her.”

The boys, always ready to shout at any mention of girls or sex, didn’t know what to say.

“She’s Pinoy, kafir. Small, skinny body, but man, what big tits,” Adel said in their cool boy talk.

The entire desert estiraha was swimming with hashish smoke. Of course, Adel waited to tell his tale when they were quite high and giggling like babies. If Adel wasn’t the hero, the leader of the group before this, he’d certainly be so now: the only one who had a girl, even if she was a Filipino.

“Ya fuckin’ liar. Bet’cha didn’t fuck no one, smart-ass,” Farid said, almost tagging Adel with a large wet clam of spit. Farid had the deserved reputation of having the juiciest spits of the whole posse.

Adel’s manhood challenged, the happy hash laughing stopped.

Ahmad was afraid Adel might hit Farid, though he’d never seen him turn violent. Whatever mischief the boys got into—spying girls, drag racing, drifting cars, smoking dope, or drinking still-made liquor—they never looked for fights or stole or really got into deep trouble with the mutaween. What if all the boyhood bullshit suddenly escalated into something really sinful?

“A man doesn’t kiss and tell,” Adel said at last.

Farid just repeated, “Ya fulla shit.”

The other boys were now quiet and seemed to move toward Farid. Adel’s leadership of the gang was on the line. Despite the red Camaro, scoring hash and booze, always the loudest when spying girls, if he now lied to the boys about actually having a girl, his role as leader would never be the same again.

Ahmad wondered what he was doing there. The hash smoke was suffocating.

“Okay, she’s my Filipino maid,” Adel said.

“The maid,” Farid shouted. “That doesn’t fuckin’ count, man.” He now spat on the ground directly in front of Adel.

Ahmad imagined the Filipino maid’s eyes looking at Adel. And felt certain Adel’s story was just made up to impress the boys. But what was the point?

That night, his father started again: when would he get a job, or at least go back to school. Mother Ahmad warned her husband to stop or he’d get another diabetic attack.

It was the first night Ahmad had gone home in more than two weeks. He now felt sorry he had. At least he was glad to see his mother, brothers, and sisters.

In the middle of the night, he turned on the TV, then, next to it, the family computer newly set up to dial the Internet. Adel had told him about a porn site online. He couldn’t find it. Farid had told him about some other site, he didn’t remember the address.

Trolling the Internet, he went from the news sites of Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya to social sites where he couldn’t get access, to religious sites where he could. He couldn’t find the right home page. He hardly slept that night but remembered a dream he’d had sometime during the morning when he should’ve already been awake and praying.

A DREAM—it caused Ahmad to hesitate and Dr. Ali to spring to life. I would soon learn that dreams held a powerful place in Saudi culture and their fundamentalist Wahhabi Islamic faith and are often considered the harbinger of divine prophecy.

Dr. Ali started in, encouraging Ahmad to reveal his dream. “Leave nothing out, Ahmad,” the doctor said. “Inshallah” (God willing).

In the Care Center prison, facing a man whose entire body was permanently disfigured from his suicide attack, I knew I needed Dr. Ali’s help if I was ever to truly know what mix of religious, cultural, political, and personal factors had led Ahmad to blow himself up.

“Inshallah,” I now knew to respond.

IN THE DREAM, his father was praying before asking Ahmad, in a very calm and sweet voice, to pray with him before he died. That was when Ahmad woke up. The news the night before had said that the king had a dream that foretold his death.

The following day, Ahmad left the house in the afternoon to hang with Adel and the gang as always.

He coughed with his first draw on the hash pipe. Maybe it was something he’d seen on the Internet or the TV the night before. He didn’t feel like being there.

Maybe it was the dream. It had been so long since he prayed. “What’s the point of all my sins?” he thought, though was quick to stop as he remembered how talking to himself had gotten him in trouble before. Instead, he asked, “Where’s Farid?”

The boys were in the middle of a video game, high anyway, and said nothing as Ahmad walked out.

He didn’t pray. His whole life didn’t amount to anything. He felt sorry for the Filipino maid, sorry for his mother. His sins would send him to Hell.

For the next couple of weeks, he wandered in and out of the gang and his house, not knowing where to go or where home really was. Then Abdurrahman, his younger brother, who had looked up to him, dropped out of school, saying he wanted to join a gang too. Mother Ahmad now pleaded with Ahmad for the sake of his brother to be a better role model and quit the gang.

Abdurrahman always got along with both his father and mother. Ahmad hoped that one day he could get along with his father too, as he did with his grandfather and mother.

Ahmad told Abdurrahman that he had quit the posse.

“Better to be a good Muslim, a good human being. Why would you want to practice a life of sin and end up burning in Hell for eternity?” Ahmad said.

“You did it,” Abdurrahman retorted.

“And now I need to repent for my sins,” Ahmad said.

Just saying the words changed him. But he didn’t know how.

He started going to mosque. And he soon got a job as a delivery boy. That lasted only a couple of weeks. He hated driving around, as he had endlessly with Adel and the other boys. No one from the gang ever called him, not even his cousin. His “friends” dropped Ahmad without a single call.

Ahmad found another job at a call center and several weeks later a better one at the Al Qassim Chamber of Commerce and Industry, near Prince Abdullah Sports City. He started with data entry, advancing to computer training. They began him at a low salary, only 1,500 riyals ($400) a month, promising to triple that after six months. After nine months, when he complained that he’d never gotten a raise, he was fired.

Ahmad couldn’t find work again, not even his old job as a delivery boy or at the call center. For a high school dropout in Saudi Arabia in 2003 and 2004, that was hardly unusual. At least half of all men under age twenty-five were unemployed.

His brother never joined a gang. Mother Ahmad doted on Ahmad as she always did. His father’s temper seemed to worsen, so he just avoided him as much as he could. Ahmad watched TV, trolled the Internet, but felt “each day was like a year,” as the Star of the East sang.

But he also went to mosque every day and said his five daily prayers. He thought of growing a beard. He wanted to redeem himself from his sins.

On Fridays, he would go to Jumu’ah prayer and hear sermons in different mosques throughout Buraydah and Unayzah. Many of the sermons were from radical clerics. Buraydah was a center of fundamentalist Wahhabi thought, and after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, jihad against the infidel invaders of neighboring Iraq became the call from the pulpit.

It was the spring of 2004. Ahmad had gone alone to a new mosque with a fiery imam on the other side of town. Then, after Friday Jumu’ah prayer and sermon, he was struck as if by a miracle from God.

He saw Adel, and Adel was transformed. Adel looked much taller than Ahmad remembered. Maybe all the time that had passed was just playing tricks. After all, it had been more than a year and a half since they last saw each other. But he could swear that Adel had grown or was holding himself taller. And Adel had a beard, pious dress. The beard changed the man.

“Cousin Adel.” Ahmad was the first to speak.

“Cousin Ahmad, God has blessed me in seeing you again.”

AHMAD HAD TURNED nineteen and Adel twenty, and they went together to Grandfather’s favorite, the oldest restaurant in Buraydah. Sitting at one of Jerusalem’s old tables, they drank gahwa, followed by sugared tea. Shunning baklava and other honeyed pastries, they ate just dates—sweet Sukkary, of course.

Adel told him all about jihad. He had learned from the imam how jihad could be a shortcut to Heaven and allow them to repent from the sins of their gang days.

Ahmad started to hang with Adel again. Rather than video games, they watched videos about Americans bombing schools. In place of surfing for porn, they surfed for jihadi websites together. They no longer talked about girls they were going to “spy” or maids they could boast about raping but together were moved by TV and Internet reports on how American soldiers were raping Muslim girls in Iraq.

Ahmad was struck by an interview on Al Jazeera of an Iraqi girl, maybe sixteen or seventeen, which the boys watched together. She had large black eyes and full lips; she showed her face but covered her hair. The poor girl could barely talk as she described how the Americans had raped her. Ahmad thought of the Filipino maid and could tell Adel was thinking of her too. It didn’t matter whether his story had been true then, it became true now.

For the next several months, they were friends again. Instead of driving fast cars, they fasted. Instead of chasing dhub lizards in the desert, they prayed in the mosque. Instead of smoking hashish, they watched a sheik on DVD issue a fatwa, which held that jihad was the surest path to forgiveness from sin. A religious friendship replaced their gang bond.

Then Ahmad saw the TV pictures that changed him.

They were of Abu Ghraib. The Americans had strung up a Muslim man as if he were about to be hanged, except his face was hooded in black and his body was completely naked. The American soldiers exposed him: everything was stripped away. The news said he had been raped.

The next shot was even more devastating. It showed the man afterward. He wasn’t any older than Ahmad. He hardly looked much different either. Ahmad could even see into his eyes. They were brown, like his, not the raging black of his father.

Ahmad could never remember feeling so moved in his life.

“There’s no greater sin than rape,” Adel said.

“We must stand up for our brothers in Iraq,” Ahmad replied, choking on the tears caught in his throat. He didn’t eat for days.

He would go to Iraq to defend his Muslim brothers. An invading foreign army was attacking innocent Muslim women and children. It was his religious duty to protect them. He was at last on the side of the good, on jihad in the way of God.

Ahmad fixed himself to follow the righteous path. The photos of Abu Ghraib called him to Holy War. To see this abuse and humiliation would call any good person, any good Muslim, to arms.

“You must swear on the Holy Qur’an not to tell anyone,” Adel said.

Ahmad stayed mute and told no one—not his grandfather, brother, or even mother. He knew his mother would just cry. He had to do this to be a man. He didn’t want to disobey his parents, but thought Grandfather would be proud. Grandfather was a good Muslim. He knew all twenty-nine times dates appeared in the Holy Qur’an; he prayed five times a day; he fasted during the month of Ramadan. And he was strong enough to know for himself what was right. Even though the Saudi government had banned Umm Kalsoum, Grandfather listened to her sing.

It was the beginning of Ramadan in October 2004. And because it was the holiest month of the year, no one would suspect he might not obey his parents.

Ahmad collected his passport, $1,600 in cash and wore his favorite leather jacket for good luck. He had gotten the jacket from his father when he was thirteen and wore it everywhere. His mother even joked that he slept in it (he sometimes did), went to the bathroom with it (well, not really), and took a shower with it still on (obviously not!).

The morning they left Buraydah, Adel and Ahmad together trimmed their beards and took on the look of their gang days. Transformed back, they seemed no different from before, but felt truly proud for the first time in their lives.

Taking a taxi from Buraydah on the highway through the desert to the capital, Riyadh, Ahmad wanted to swing by his grandfather’s Prince Mishal store on the way out of town.

“We can’t take detours from our mission, Cousin,” Adel said.

It was the first time that Ahmad had ever left his hometown, the International Capital of Dates. Now he’d be truly international—not something just any boy from Buraydah could boast of.

They stayed in a run-down hotel, the Al Mutlaq, which Adel had found in the center of Riyadh on the Old Airport Road. It was not much better than the estiraha near Buraydah they had hung at: smoky old lobby with deep red curtains and paintings of date palms and camels peeling from the cracked green walls. Their room was small and smoky too.

Ahmad had trouble falling asleep that night without his mother’s glass of hot milk. But he hoped that “the best mother in the whole wide world” would one day understand.

Adel gave Ahmad the contact phone number and meeting place in Syria he got from his imam and said from now on they must act as if they didn’t know each other. Each taking their own taxi to King Khalid International Airport, they checked in separately. Ahmad did not need a visa for Syria.

The Saudi Airlines flight to Damascus put pressure on his ears. He could barely hear all the instructions the flight attendants gave.

He took another taxi to the Marjeh Square Hotel, off the town square near Old Damascus. It was another beat-up hotel like the Al Mutlaq. This time the paintings of date palms didn’t even look like the real thing. He supposed the Syrians didn’t really know.

They played Umm Kalsoum in the lobby, music now forbidden to him as a jihadi. It was even “Aoulek Eih” (What Should I Tell You?). He recognized every sway of the violins, every off beat of the drums—most of all that voice, wailing, pleading, crying for mercy, moving up and down scales, from her deepest guttural pleas to her fluttering, gasping trills, giving him goose bumps all over. The Noble Lady had once held millions of Arabs in tarab. On every record, you could hear all the men screaming, clapping, and singing along with the world’s greatest singer—no Arab was more beloved. Ahmad imagined that it must have been a simpler time than now. Why did the Americans have to attack? He even remembered another of Grandfather’s favorites, “The Time Has Passed”: “Tell Time to turn back, turn back for us once more …”

Ahmad never left the hotel to explore Old Damascus. From the taxi, it looked so much more crowded than Buraydah. Leaving separately, he hadn’t seen Adel at the airport or hotel. Ahmad was sure he was on the right path, even if sweating. It was a great feeling of adventure he had never known before. It was a duty to God. He had seen Abu Ghraib. If those photos didn’t move you, nothing would.

Ahmad called the number from a phone booth in the hotel lobby at precisely 20:00 hours, just as he was supposed to. After he made the call, he saw a guy walk by and signal him with his eyes. He followed the man outside, who told him to follow another man at the next corner. It was hard to keep up with the next man through the back alleys of Damascus, but they soon arrived at another hotel, climbing the narrow stairs to the third floor. The man, whose face was covered, asked for 500 riyals ($150) and Ahmad’s cell phone. He told Ahmad to keep wearing his black leather jacket (no problem!) and carry today’s newspaper in his left hand (“More American Massacres in Iraq,” the headline).

“Go to the Al Amir Hotel in Aleppo and the phone booth in the lobby, call this cell.” He handed him the back of a folded cigarette box with a number written on it.

Every time he had to move, Ahmad felt important. What was he doing in Buraydah? Now he was helping his Muslim brothers against an infidel invader. Every time he had to go to a back alley or make a phone call, he was following in the way of God. It didn’t matter that he had lost touch with Adel. He was on jihad. Ahmad al-Shayea was living Islam.

He took the bus to Aleppo at six the next morning, found the hotel near Aleppo’s Old City, and made all the calls he was told to.

At last he saw a taxi pull up to the hotel and Adel come out with a Syrian. They all went off in the cab together.

It was wonderful to see Adel again, even if they didn’t talk.

Mazen was the new Syrian handler from the “Tawhid and Jihad Group,” under the command of the famous Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Al Qaeda’s commander in Iraq. Mazen was short, no taller than Ahmad in fact, but had an enormous chest with bulging biceps and a three-day growth across his face. His words were clipped and harsh. He told the boys to read their newspapers in the cab and not look where they were headed.

They came to another decaying building in the old souk and climbed the steep stairs to an apartment on the second floor. The Syrians led Adel in a different direction, and Ahmad was now with two Moroccans, another Saudi, and a Syrian. They were curtly told not to leave the apartment, just watch jihadi videos set up for them, and in the evening, for iftar to break the Ramadan fast, eat the hummus and Syrian bread. It was a pale imitation of the Lebanese dishes at the Jerusalem Restaurant. Ahmad missed his Sukkary dates.

None of them talked much. The guys were here to defend Muslims, promote Islam, and expel a foreign invader. There was no room for chitchat. Or for Ahmad to wonder where Adel was.

The next day, Mazen drove them in a van with curtains to a farm outside Aleppo. There were more Saudis and North Africans, only no Adel.

Mazen was in charge. He said that the road to the battlefield in Fallujah was not clear. The men spent the next ten days watching jihadi videos of the suffering of Iraq.

Ahmad got up all his courage to speak to Mazen. He asked the burly Syrian to contact his parents and let them know he was safe. He handed Mazen his father’s number in Buraydah.

“Don’t worry ’bout it, kid,” Mazen said, pointing his stubby index finger. Ahmad noticed that he had no nails.

On the tenth day, Mazen took each man into a private room. He sat Ahmad down. Without saying a word, Mazen handed him a fake Iraqi ID, 500 Syrian liras, and a bus ticket. He told him to leave tomorrow, wait under the pharmacy sign at the end of Tal Abyad Street in Raqqah. The pass code was “helilmoya” (“sweeten the water”), a traditional Bedouin greeting.

“Did you reach my parents? Let them know I’m all right?” Ahmad asked.

“Told you not to worry ’bout it, kid. Not a problem.”

Mazen needed Ahmad’s Saudi passport and any money he had left. Mazen didn’t say anything but motioned with his hand for more.

“That’s all I have,” Ahmad said.

Mazen kept calling with his hand: “The jacket, kid.”

It was Ahmad’s prized possession. The lucky leather jacket his father had given him and his mother had always joked about. He’d promised it to his brother Abdurrahman. He now wished he’d just left it at home in Buraydah. He was sure it wasn’t worth much. Why did the Syrian need it anyway? It was just lucky to Ahmad. It made no difference to anybody else.

He didn’t know what to do. Tell Mazen it was lucky? He’d sound like a kid, not a jihadi fighter. A lucky jacket was hardly pious.

“You’re a soldier in jihad. I’m your superior officer. I’ve given you an order. You want me to call your father, don’t you?” Mazen barked.

He took off his lucky jacket and handed it to the Syrian, wondering whether he’d sell it in Aleppo’s famous souk the next day.

Mazen just said, “Dismissed.” Ahmad felt his throat well up and was about to say “Please call my parents,” when Mazen shouted “Dismissed!” almost at the top of his lungs.

Ahmad felt like crying, but wasn’t a baby, he told himself. He was here as a jihadi to fight for justice. What did a silly childhood jacket mean? And if the money went for jihad, it would bring him even more luck in the battles ahead.

UNDER THE SIGN, Ahmad waited. It was only a couple of minutes. It felt like forever. He was cold. He’d gotten so used to that stupid jacket. He wondered where Adel was. No one had ever told him they’d be separated like this. His ears felt full, as on the plane. It almost made him feel dizzy.

He began to pace under the sign. The pharmacy looked like his grandfather’s Prince Mishal store, if you thought hard enough.

At last, a stranger came and muttered “Helilmoya” under his breath so quickly Ahmad could barely make it out. They all talked so curtly. But that must be the way of real soldiers, he thought. Told to look down, they walked in circles around Raqqah town, to a ground-floor apartment and a group of four other Saudis and Adel at last.

Ahmad felt so relieved to see him. They embraced but didn’t talk. It was not the jihadi thing to do. He knew he couldn’t tell Adel about his jacket, even though he was dying to. Friendship now meant something different. They were comrades in arms, not boys from Buraydah.

Two days later, they left Raqqah for the town of Dayr az-Zawr, closer to the Syrian border with Iraq. Riding in another van with curtains, they were like women veiled. Still, Ahmad was happy: Mazen had put Adel in charge of the Saudis.

Ordered into the back of a truck, hiding underneath soap, laundry detergent, and other cleaning supplies, the men then went to Abu Kamal on the Syrian border with Iraq. At near midnight, the Syrian smuggler, “Abu Muhammad,” he called himself, wearing his night-vision goggles and Kalashnikov, led the men on foot into Iraq. They crossed near Al Qa’im, the Iraqi border town in Al Anbar Province.

They had made it inside. The Syrian now handed the new jihadis to an Iraqi, “Abu Asil, the Prince of Arabs,” he called himself. The prince led Ahmad and the other boys to the safe house, a farm near Al Qa’im.

The prince cut a commanding figure. Unlike the Syrians, he was tall and thin, with full Arab headdress and beard.

Gathering the group together the next day, Abu Asil, prince of the Arabs and emir of Al Qaeda in Iraq in Al Anbar, addressed them as “valiant jihadis.” Twenty-four men from all over the Arab world: five Saudis and nineteen from Jordan, Morocco, Yemen, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt.

At last they were in Iraq, ready to fight for their Muslim brothers and defend Islam against the American torture and humiliation of Abu Ghraib.

“You soldiers of jihad have arrived at the time of God’s greatest glory. The battle against the infidel American invaders is joined. Your sacrifice at Fallujah can defeat the Jews and Crusaders,” Abu Asil said.

Ahmad had never felt so proud.

“How many of you will die to avenge Abu Ghraib?” the prince demanded.

“Allah-u-Akbar!” (God is great) they all cried, to a man willing to avenge the shame visited on Muslims at the satanic Abu Ghraib.

“Those most blessed among you in God’s eyes,” the emir continued, “are noble shaheed ready to go to Heaven on a martyrdom mission for Allah Almighty. Whoever wants can leave with me at the vanguard, leading all of you.”

There was silence. Maybe the boys had not clearly understood the prince’s words.

Abu Asil explained with a fatwa: “Every martyr will go straight to Heaven, in ultimate glory, there is no higher calling. So each of you is called, so each of you shall go.”

Again, there were no cries of “Allah-u-Akbar,” not even a word.

Ahmad came to Iraq to fight to defend the honor of Islam against Abu Ghraib and American torture, not die right away in a suicide bombing before he could even save a single soul. Ahmad thought Adel and the others must feel the same way, as Abu Asil continued to exhort the group to suicide missions but no one volunteered.

“Soldiers of God will do what jihad requires. Every one of you will in time be worthy of Al Qaeda in Iraq.”

The next day, Abu Asil led the new soldiers in more vans to another safe house in Rawah, near Anah. And farther down the Euphrates River in Al Anbar Province awaited the scenes of battle and glory: Hadithah, Ramadi, and Fallujah.

But the men just waited. Day after day. The dirt stuck to the food—not like the real Arab food Ahmad was used to eating. Iraqi flat bread, khubz mostly or samoon, hummus, sweet watery tea, crusty date jam. The Khadrawy dates were dried and hard, not Sukkary sweet and moist. Ahmad had diarrhea and was embarrassed how much time he spent at the shithole.

There were some forty-five jihadis now, many just returning from battle in Fallujah. They didn’t say much except pray five times a day. None of them was Iraqi, except for Abu Asil the emir, who took his orders directly from Zarqawi, the highest commander of Al Qaeda in Iraq. The days were spent waiting. They did allow the men to hold a Kalashnikov, but not shoot it. The shamal winds were fiercer than in Buraydah.

At least Adel was there. Ahmad always prayed shoulder to shoulder with him in true jihadi fashion. Adel was the only one he talked to. But all Adel kept saying was “Remember Abu Ghraib. Never forget what you saw with your own eyes, Cousin.”

Who knew TV photos could call you to fight, give up your whole life?

After almost three weeks, the emir told Ahmad that he and another Saudi would go to Ramadi, closer to the front.

But the other Saudi wasn’t Cousin Adel.

Separated from Adel, Hamzah made a poor substitute. Fat with a long stringy beard and crooked teeth, his skin was dark as a dried Khlas. Hamzah didn’t seem to know much about anything. He was from Asir, the southernmost province in Saudi Arabia. A real tribal, he kept saying that the emir had promised him “sweet Heaven” and seventy-two houri (virgins) in a martyrdom mission. Hamzah was just after some reward. What about helping his fellow man on Earth right now? Ahmad thought. Weren’t they fighting to stop Abu Ghraib and the infidel Crusaders? He wondered how Hamzah could stay so fat on such lousy food. Ahmad could hardly sleep, waiting and waiting, while Hamzah just got fatter and fatter.

The next long month and a half brought no fighting. Ahmad and Hamzah would shuttle from Iraqi safe house to safe house to avoid the Americans, though Ahmad never saw any. And there was no training at all. Not even how to shoot the Kalashnikov that they had once been allowed to hold.

His diarrhea wouldn’t stop. There were no real dates to fortify him, no Cousin Adel to urge him on. Hamzah, the hick Asiri, would talk of the “eternal beauty” of the virgins and how he’d drink the “sweet juice of Paradise while a virgin beauty wiped his mouth.” Ahmad hoped to God that nasty Syrian had at least called his parents. He tried to remember Umm Kalsoum, “Hadeeth El Roh” or “El Atlaal,” but there was no music. He worried Grandfather might be sick, or maybe his mother. Ahmad could cry with her as he’d never cried while reciting the Book.

Ahmad kept telling himself it was time he became a man, stand and fight for his Muslim brothers. Remember Abu Ghraib. Finally, when Abu Asil stopped by to check on them, he got up all his nerve to complain.

“I want to fight like a soldier for jihad,” Ahmad said. His stomach hurt, he even felt tears.

The Iraqi told him security was hard now and be patient. They always said be patient. “We will give you a sacred mission,” he promised.

Shortly after, another emir, higher up than Abu Asil, came. He called himself Abu Osama and said he was the highest leader of Al Qaeda in all of Al Anbar Province. He would take Ahmad on a mission to Baghdad.

“Al-Hamdulillah,” Ahmad said, nodding. Praise God.

Ahmad felt his whole life leading to this point. After nearly three months in purgatory, he would finally have the chance to help others and serve God.

Taken to the safe house of Abu Omar al-Kurdi in Baghdad, he spent the night with two other Saudi soldiers of God and a Yemeni. He wondered where Adel was now and what his brother Abdurrahman, his whole family was doing. He wished he could just call them.

Three days later, Ahmad was taken to yet another safe house, still in Baghdad, this time with nine Iraqi fighters.

Adel wasn’t there. In fact, there were no foreign Arabs. Ahmad was now the only Saudi among all the Iraqis.

His new emir, Abu Abdul-Rahman, hardly looked the part of a pious jihadi. He had an oily stubby beard and always a cigarette in his mouth—or was busy lighting one to stick inside. The cigarettes even had an American name: Miami. Ahmad found it strange that this great Iraqi jihadi with yellow fingers and hands always smoked a Miami. Even his toes were stained yellow. He felt like asking if the emir smoked with his toes too, but Ahmad had a sacred mission for jihad.

And his first mission, Abu Abdul-Rahman now told him, was to deliver a fuel tanker to Al Mansour, a Baghdad neighborhood, where it would be picked up by other jihadis.

“I don’t know Baghdad at all,” Ahmad said.

“We’ll help you, my son.” The emir managed to smile without ever removing the Miami from between his lips. But Ahmad could see that his teeth were yellow and tobacco-stained like his fingers and toes.

Ahmad felt cold. The headache between his eyes grew stronger. He had never trained for this. He didn’t even know how to drive a tanker. Then again, he had never trained for anything. And after almost three months of waiting, waiting to fight, to help, to do anything at all, he didn’t want to refuse.

That evening, Ahmad performed final Isha prayer with the Iraqis and had dinner—a dish of chicken and eggplant, the best since he had arrived in Iraq. It tasted almost as good as the food at the Jerusalem Restaurant, but not as good as the Sukkary-sweet jareesh of “the best mother in the whole world.”

His stomach was on edge again. He tried to think of something that would help him sleep. Umm Kalsoum. He wasn’t allowed to sing anymore, even to himself. Sukkary dates. He had a hard time remembering their sweet taste. The eggplant stuck in his mouth. He was scared it would give him diarrhea in the middle of his mission tomorrow.

Ahmad had to find the strength. He called the pictures of Abu Ghraib to mind. One of the Iraqis had said the hellish prison was not that far from them. He thought of all the young men like himself being held there, raped and beaten by the American Crusaders. He felt their pain in the pit of his stomach, his head pounding as if he too was hanging by his neck at Abu Ghraib. The jihadis told him the American Crusaders and Jews would not rest until they killed every last Muslim. Ahmad knew that only God could give him the strength. He just hoped his father would know all he’d sacrificed.

It was a rather cool day for Baghdad, even at the end of December 2004. Ahmad wished he still had his leather jacket. The emir handed him a simple hand-drawn map from his yellow fingers. With a Miami firmly stuck between his crooked teeth, the emir assured him that two Iraqi jihadis would be with him every step of the way.

“Abu Abdul-Rahman, my emir, I have but one request.” Ahmad tried to talk in the most formal florid Arabic, with its traditional words of deference and obeisance. Maybe the emir didn’t even understand.

“Stop worrying, Abu Omar and Muhammad Odeh are going with you. You’ll not be alone.” The emir’s foul tobacco breath made him want to recoil.

“Not that—” Ahmad said. He lost his words. His hands were shaking. His cheeks were red, even though his beard was now fuller and longer than it had ever been in his life. His whole body was cold. He was afraid he’d shit in his pants.

“I have but one request,” he repeated in formal Arabic.

“Spit it out, my little son,” Abu Abdul-Rahman said, inhaling his Miami with such force he could’ve swallowed the lit cigarette whole.

Ahmad thought of his grandfather—and Farid, “the Spit Champion of Buraydah.”

“After the mission, can you arrange for me to call home?” He didn’t want to sound like a kid.

The emir smiled through his tobacco teeth. “Of course, it would be my greatest pleasure, my smallest son,” he said in the most formal manner that apparently he could muster.

AHMAD WALKED BEHIND Abu Omar and Muhammad Odeh. The two Iraqi jihadis were not much older than Ahmad. Not much taller or bigger either.

Each step Ahmad took his stomach turned, until he let loose a large fart. He hoped to God the other men didn’t hear it. But he farted again even more loudly. The whole neighborhood could hear it now. Ahmad burst out laughing. He couldn’t stop.

“You’re a real Saudi,” Abu Omar said.

“It’s the eggplant,” Ahmad said, still laughing like a desert camel.

“No, you’re Saudi. You guys are the loudest.” Abu Omar chuckled now too.

The tanker truck parked around the corner was much larger than Ahmad had imagined. The other jihadis told him to get in the driver’s seat. He had no clue how to drive it.

But the Iraqi jihadis were nice. Before they drove anywhere, they let him practice. The clutch worked smoothly. And he didn’t have to worry, they told him: they’d start driving the tanker first toward the center of town themselves.

Abu Omar took the steering wheel. He was the nicest of the Iraqis. Ahmad sat in the middle...

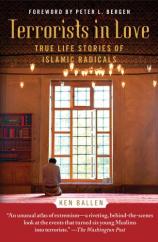

Terrorists in Love

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Free Press

- ISBN-10: 1451672586

- ISBN-13: 9781451672589