Excerpt

Excerpt

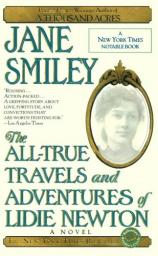

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

Chapter 1: I Eavesdrop, and Hear Ill of Myself

Let every woman, then, bear in mind, that, just so long as her dress and position oppose any resistance to the motion of her chest, in just such proportion her blood is unpurified, and her vital organs are debilitated.

--Miss Catherine E. Beecher, A Treatise on Domestic Economy, for the Use of Young Ladies at Home, p. 117

I have made up my mind to begin my account upon the first occasion when I truly knew where things stood with me, that is, that afternoon of the day my father, Arthur Harkness, was taken to the Quincy graveyard and buried between my mother, Cora Mary Harkness, and his first wife, Ella Harkness. My father's death was not unexpected, and perhaps not even unwelcome, for he was eighty-two years old and had for some years been lost in a second childhood.

I could easily sit beside the floor grate in my small former room above the front parlor of my father's house and hear what my sisters were saying below. The little bed I had slept in as a child was pushed back against the wall to make room for discarded sticks of furniture and some old cases. I sat on a rolled-up piece of carpet.

Ella Harkness's daughters numbered six. Of those, two had gone back to New York State with their husbands. Our three, Harriet, Alice, and Beatrice, were all considerably older than I, the only living child of the seven my mother had borne. Miriam, my favorite of the sisters, a schoolmistress in Ohio, had died, too, of a sudden fever just before Christmas. Some twenty years separated me from Harriet, and all the others were even older than she was. I had many nephews and nieces who were my own age or older and, it must be said (was often said), better tempered and better behaved. Some of my nephews and nieces had children of their own. I was what you might call an odd lot, not very salable and ready to be marked down.

"I don't want to be the first to say . . ." I could see Harriet from above. She squirmed in her seat and smoothed her black mourning dress for the hundredth time. She wore the same dress to every funeral, and the only way we'd gotten her into it this time was to lace her as tight as a sausage. The others let her be the first to say it. I leaned back, so my shadow wouldn't fall through the grating. "It don't repay what you feed her, since she don't do a lick of work."

"She an't been properly taught's the truth," said Beatrice, "but that's her misfortune." No doubt here she threw a look at Alice.

"I've had my own to worry about," complained Alice. Since Cora Mary's death, I'd been seven years with Alice. The easiest thing in the world for Alice was to lose things--her thimble, her flour dredger, her dog. If you wanted to stick by Alice, then it was up to you. She was a churchgoing woman, too, but whenever she forgot her prayers, she would say, "If the Lord wants me, he knows where to find me." That was Alice all over. Needless to say, I generally found myself elsewhere, and I would wager that was fine with her. Her own brood numbered six, mostly boys, so they were more often than not busy losing themselves, too. It was my niece Annie who kept the engine running at Alice's. Right then, in fact, Annie was out in the kitchen, getting our tea. It wouldn't have occurred to Harriet, Beatrice, or Alice to lift a finger to help her. It occurred to me, of course, but that hole of kitchen work was one I didn't care to fall into, because it was easy to see how those women would pull up the ladder, and there you'd be, hauling wood and water, making fires and tea, for the rest of your life.

"We could have sent her on the cars to Miriam. Young people her age seem to go on the cars without a speck of fear. Or Miriam could have come got her." This was Harriet.

They pondered my sister Miriam, a spinster who'd taught reading to little Negro children in Yellow Springs. Harriet's tone revealed some sense of injury that Miriam was no longer capable of being of use in this way. But Miriam had been a strict woman, the sweetest but the strictest of them all. Her fondness for me had been mostly the result of the distance between us and our lively correspondence. I knew that even if Miriam were still living and I had gone to her on the cars and tried to stay with her, the sweetness would bit by bit have gone out and the strictness bit by bit come in. But I missed her. "Miriam was genuinely fond of her." Beatrice expressed this as a great marvel.

"Where is Lydia?" The sofa emitted a heavy groan. Harriet must have leaned forward and looked around for me.

"Outdoors," said Alice, and I would have been, too, but my heavy mourning dress, wool serge and buttoned to the throat, gave the sunny summer hillside that was my usual resort all the attractions of the Great Sahara Desert. I had crept upstairs and undressed down to my shift. The black armor I would soon need to don again seemed to hold my shape where it lay over the back of a chair. I lifted the hem of my shift and fanned myself with it. "Out in the barn, most likely." Alice amplified her speculation with all the assurance of someone who never knew what she was talking about.

"Oh, the poor orphaned child," exclaimed Beatrice, and for a moment I didn't realize she was speaking of me. "Alone in the world!"

"She's twenty years old, sister." Harriet's tone was decidedly cool. "I was safely married at twenty, I must say. If she's without suitors, who's to blame for that?"

"And she has us," said Alice.

Oh, the poor orphaned child, I thought.

It was true as they said that I was useless, that I had perversely cultivated uselessness over the years and had reached, as I then thought, a pitch of uselessness that was truly rare, or even unique, among the women of Quincy, Illinois. I could neither ply a needle nor play an instrument. I knew nothing of baking or cookery, could not be relied upon to wash the clothes on washing day nor lay a fire in the kitchen stove. My predilections ran in other directions, but they were useless, too. I could ride a horse astride, saddle or no saddle. I could walk for miles without tiring. I could swim and had swum the width of the river. I could bait a hook and catch a fish. I could write a good letter in a clear hand. I had been able to carry on a lively dispute with my sister Miriam, who'd been especially fond of a lively dispute.

Worse, I was plain. Worse than that, I had refused the three elderly widowers who had made me offers and expected that I would be happy to raise their packs of motherless children. Worst of all, I had refused them without any show of gratitude or regret. So, I freely concede, there was noth-ing to be done with me. My sisters were entirely correct and thoroughly justified in their concern for me. It was likely that I would end up on their hands forever, useless and ungrateful.

I stood up and moved away from the vent, suddenly weary of the certain outcome of their speculations. Back to Alice, back to the strange languor of that life. It vexed me, too, that though their afternoon of complaint and self-justification would result in nothing new, they would make their way through it, anyway, like cows following the same old meandering track through their all too familiar pasture and coming upon the same old over-grazed corner as if it were fresh and unexpected.

I looked out my window upon the slope in front of my father's house. There had been no funeral supper, none but the quietest and most subdued gathering of the few around town who'd known my father. Each of my sisters' husbands had returned to his business or farm directly from the graveyard. All of us, I knew, would find a way to put off our mourning clothes as soon as possible. Even before my father lost himself, he was a silent and vain man. Just the sort of man who would approach a plain woman like my mother without the least pretense or compunction and invite her to leave her own parents and come over to him, to care for his six daughters and bear him a son. He had been fine to look at, with glossy curling hair and full whiskers. Perhaps she was gratified at being chosen at last for the very usefulness she had cultivated so long.

My hair, as usual, was falling about my face. I unpinned it, set the pins in a row beside my small looking glass, and picked up my brush. My hair was long and thick. As I lifted it off my neck and pulled the brush up underneath it, I couldn't help feeling that in spite of every iota of evidence to the contrary, something was about to happen.

My sister Beatrice's husband, Mr. Horace Silk, sold dry goods on Maine, at Lorton and Silk. Mr. Jonas Silk, the old man and Horace's father, held the reins of the business in a tight grip. Lorton was long dead. As a result, Horace was as little consumed by his interest in calico and muslin as he was much consumed by his interest in western land. Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas--the walls of L and S Co. were papered with bills that offered, for a fair and reasonable sum, city lots in lovely, tree-shaded towns, country farms watered by sweet flowing streams, gristmills, sawmills, ironworks, every sort of business. Brother Horace and his cronies pored over the bills, comparing and contrasting the virtues of every region, every town, every named river and stream. They were forever putting together their investments, forever outlining schemes, forever scouring their relatives for funds, but in truth Mr. Jonas Silk was as niggardly as he was jealous, and my sister Beatrice had as much interest in Kansas as she did in the czar of all the Russias, and so my brother Mr. Horace Silk worked out his plans in a white heat of frustrated eagerness.

Of all the women, it was only I who listened to the men, though I made no show of doing so. The towns I favored numbered three: One was Salley Fork, Nebraska, where the grid of streets ran down a gentle southern slope to the sandy, oak-shaded banks of the cool, meandering Salley River and where the ladies' aid society had already received numerous subscriptions for the town library, which was to be built that very summer. Town the second was Morrison's Landing, Iowa, on the Missouri, where the soil was of such legendary fertility and so easy to plow that the farmers were already reaping untold wealth from their very first plantings. The third was Walnut Grove, Kansas, where the sawmill, the gristmill, and the largest dry goods emporium west of Independence, Missouri, were already in full operation. Horace himself had a fancy for a farm on the Marais des Cygnes River in Kansas, which was the finest farming land in the world and, according to the bill, located in the best, most healthful climate--just warm enough in the summer to ripen crops, always refreshed by a cool breeze, and never colder in the winter than a salubrious forty degrees. Fruit and nut trees of all varieties, bramble fruits, and even peaches were guaranteed to grow there.

For many months, one of my main pleasures in life had been to linger in L and S, prolonging my errands there for Alice and gazing upon the delightful bills, with their neat street maps and architectural drawings. Quincy, which had been a mere handful of buildings when my father arrived, seemed old and run-down by comparison. Even so, my chances of getting to any of these places seemed at least as remote as Horace Silk's, and as often as I gazed upon my favorite bills, I also vowed to put away the thoughts that agitated me. My sisters were as fixed in their various homes as stones, and as difficult to lift. I had no money of my own and no companion. Even my father's old horse had died some three years before, never to be replaced, since my father had no use for a horse. That horse was the last familiar creature that he remembered the name of. As recently as six months before his death, sister Beatrice found him in the barn, looking at the horse's empty stall and muttering, "Wellington." That was the horse's name, after the duke himself.

I turned from the glare of the window and crept back to the carpet roll. There I squatted and peered down. Harriet was fanning herself. Her face was bright red. Beatrice was saying, ". . . a nice chicken business."

"And where," said Alice, "would we set her up with this nice chicken business? And . . ." She paused and caught her breath indignantly. "If Horace is going to set anyone up in a nice chicken business, then in my opinion Annie is far more deserving and would certainly do well at it. Annie gets very little consideration, I must say. You have more room on your farm, Harriet, for any sort of nice chicken business than we have on our town lot, a double one though it may be and as big as any." "I know the end of that," complained Harriet. "More work for me when she lets her chickens run wild. I have my own chickens, as many as I can handle."

I wanted to shout down through the grating that every woman in Quincy had a nice chicken business, that the chicken trade was over-subscribed, but I held my tongue.

"I still think," continued Harriet, "Beatrice . . ." There was a portentous pause while Harriet made sure to stake her claim to Beatrice's full attention. "Bonnets! She can trim bonnets for Horace and Jonas. She's all thumbs with a needle, but--"

"Lydia is all thumbs!"

"Annie, on the other hand, has a tremendous gift for trimming bonnets! She--"

I let out a single stifled bark of merriment. Harriet looked around, startled, but didn't guess where the noise was coming from. I have to say, though, that my sisters' ventures into the question of what was to become of me had taken an unexpectedly creative and comic turn. It was clear that I would have to make an effort, or I would soon find myself gainfully employed.

Below me I saw the top of Annie's head glide into view, neatly juxtaposed to a large round tray covered with tea things. The severe white parting that ran from the front of that crown to the back was so fine and straight it might have been done with a knife point.

"Shh," said Harriet. "Thank, you my dear. Lovely."

It was a principle of the family that no business was discussed in front of Annie, who was generally considered too innocent to withstand the shock of most topics, though of course not too fragile to be worked to death. They did not invite her to take tea with them, so she set down the things and once again removed herself.

"This whole question," said Alice, "is too much for such a day as this. We've just buried our dear pa, after all."

"He was a fine-looking man," said Harriet. "The very picture of a patriarch."

"Mrs. Rowan said he was the fairest creature of either sex she ever saw. She told me that yesterday when she was in buying sugar," said Beatrice. "'He cut a wonderful figure.' Those were her very words."

They all sighed.

Excerpted from The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton © Copyright 1998 by Smile-Mor, Inc. Reprinted with permission by Fawcett. All rights reserved.

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

- paperback: 480 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0449910830

- ISBN-13: 9780449910832