Excerpt

Excerpt

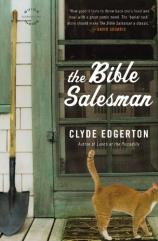

The Bible Salesman

1950

A man driving a new Chrysler automobile along a dirt road near the North Carolina mountain town of Cressler saw a boy up ahead, dressed in a black suit, white shirt, black tie, with a suitcase and valise by his feet. The boy was standing in front of a grocery store, thumbing a ride.

The man, working his way up, belonged to a crime outfit. He was now at the car-theft level, hungry for wealth and the tense excitement he found nowhere outside crime.

The boy was a twenty-year-old Bible salesman whose aunt raised him to be a Christian gentleman. He was hungry for adventure and good food. He had recently started reading the Bible on his own rather than as directed by his aunt and church elders, and he hadn’t been able to get past those first two chapters of Genesis—because they amazed and confused him.

The man thought he recognized something smart and businesslike in the boy’s stance—almost at attention—and he also sensed some gullibility and innocence. His last associate had not worked out. He slowed and pulled over in the rising dust. If this one didn’t seem promising, he’d just let him out down the road.

The boy loaded his things into the backseat, closed the back door, bent his head forward, and folded into the front passenger seat. The man noticed the boy’s leftover belt end hanging down freely without being put through the first loop, his hair standing up on top in back. Maybe he won’t so smart.

“Nice car,” said the boy. “ ’Fifty Chrysler.” He reached out his hand. “I’m Henry Dampier.” Henry was surprised at the man’s big hand. And he had big ears. He looked a little bit like Clark Gable, but without a mustache.

“Preston Clearwater,” said the man. “Where you headed?”

“Anywhere south. Where it’s a little warmer. I came up here earlier than I ought to have.” The man was dressed up neat, and he’d shaved real close that morning, it looked like. He’d have a dark beard if he grew it out. He was wearing cuff links, and Henry had never seen those except at a prom.

“I’m selling Bibles,” said Henry. “But it’s too cold sleeping in warehouses and barns up in this high altitude.” He noticed how smoothly the car glided over the dirt road. “Where you headed?”

“Winston-Salem, or maybe Charlotte—for tonight, anyway.”

The night before, Henry had sat up late in a deserted warehouse razoring out the front pages of new Bibles that had arrived in Cressler, general delivery—from Chicago—in a cardboard box. Each page said, “Complimentary Copy from the Chicago Bible Society.”

Henry looked at Mr. Clearwater’s hands. They were clean. “What line of work you in?”

None of your goddamned business, thought Clearwater. “Car business,” he said. He pulled out a pack of Luckies, shook up a couple. “Cigarette?”

“Sure.” Henry had bought his first-ever pack of cigarettes only a few days earlier.

Clearwater pushed in the cigarette lighter. “Where you get your Bibles?”

“Where do I get my Bibles?” Henry looked at him. Could he know somehow? “That’s kind of a long story.” He did want to tell about it—this idea he got from the fiddle player at Indian Springs in Cressler: instead of ordering Bibles and having to pay, why didn’t he just go ahead and order a box from one of those places up north, or in Nashville, Tennessee, maybe, that gave away Bibles, tell them he had a bunch of sinners to give them to, razor out the pages that said they’re free, and sell them? The fiddle player said he’d had that idea when he thought about selling Bibles himself, but gave it up when his wife had twins and his mama died. Henry had wondered if he was kidding, but took the idea anyway.

So Henry had been ordering a box of free Bibles about once a month, each from a different place so that nobody got suspicious. In the letter to them he kind of hinted that he was a preacher. But nobody got hurt, and in the end more people ended up reading the Bible, which was good, and now his billfold, his spare billfold—stashed in his suitcase—was considerably thick with money, somewhere between forty and fifty dollars, and some uncashed checks. He could go ahead and stay in a decent room for a change. And now here he was riding in a brand-new Chrysler. With a man who looked like he knew how to do things out in the world.

“This smells like a new car too,” said Henry.

“It’s pretty new.”

Henry noticed the ivory-looking knob on the end of the gearshift—he couldn’t quite see the top speed on the speedometer. “Six or eight?” he asked.

“Eight. Hundred and thirty-five horsepower.”

“That’s pretty good. So, do you sell cars?”

“Yeah.” Clearwater, with his lips closed, passed his tongue over his front teeth. “I do that.”

Henry figured he’d be quiet, give Mr. Clearwater a chance to kind of talk or not talk. He didn’t want to chitchat himself into getting dropped off somewhere.

“Where you from?” asked Clearwater.

“Simmons, North Carolina. Down east.”

“Is that anywhere close to McNeill and Swan Island?”

“About an hour or so. I went there a few times when I was growing up.”

“I know some people there. Mitchells.”

“I don’t know any Mitchells down there. My uncle took us all there one time—me and my sister and aunt—to see this big dance hall that was one of the first places in North Carolina that used electricity fancylike. They showed movies on a screen set up in the surf.”

“I heard about that.”

Clearwater’s boss, Blinky, owned a warehouse in McNeill that held some stolen army equipment. It was part of Blinky’s cover—a business called Johnson and Ball Construction and Industrial Machine Repair Company.

The drive to Winston-Salem would take three or four hours. Clearwater began to feel Henry out, learned that he was raised by his aunt and uncle. That his daddy got killed right after Henry was born, hit by a piece of timber sticking out from the back of a moving truck. That he was a Christian. That he liked baseball and had played on a church team coached by two men who worked at a funeral home and used baby caskets to hold the bases and other equipment. That he went to Bible-selling school instead of business school and was taught to sell Bibles by a man who walked back and forth in front of the class, chain-smoking cigarettes and coughing and telling funny stories. That he had an older sister named Caroline and an uncle he liked to talk about—Uncle Jack. And a cousin—Carson. And though Henry didn’t say it, Clearwater could sense he was a virgin, because of how he’d talked around some stuff about women. That was good—it’d help both of them stay out of woman trouble if he did hire him.

He also found out the boy knew when to shut up—when Clearwater was talking. Damned important. And he seemed to have an adequate sense of adventure without a too-big portion of carelessness. In fact, Clearwater felt a little bit lucky to have found this Henry Dampier.

Along about Wilkesboro, down out of the real mountains and into hilly country, Clearwater pulled over, stopped, and asked Henry to drive.

The boy was clearly happy to be behind the wheel of a car, and he was a good driver, kept his eye on the road, didn’t go too fast, drove around holes. Clearwater talked some about his own service in the army, in France. He didn’t tell Henry he’d met Blinky there and that they—with creative paperwork and bold presentations of self—managed to steal two dump trucks, a forklift, four jeeps, seven chain saws, and sixteen hundred pairs of aviator sunglasses. Blinky had them shipped to a warehouse in McNeill owned by his Aunt Thelma, the nonsuspecting wife of his dead uncle, Gabe Mitchell. He told Henry he’d been to business school, but he didn’t tell him that that had slowed him down and left him behind Blinky in the crime business—and now he was trying to catch up. He told him some stuff about his communist mama, who believed in Jesus. She believed the Indians were communists and that Jesus was a communist. Course you couldn’t talk about the communists now without somebody thinking you were one, Clearwater said, like he always said when he talked about his mama. And this Henry Dampier knew something about the Russians and Chinese and the atom bomb, more than he could say about some of the potential associates he’d come across since he’d turned loose his last one. And even though all that was true about Clearwater’s mama, a lot of people didn’t believe it, but this one seemed like he did, so Clearwater reckoned he was maybe gullible enough.

They stopped in Winston-Salem in the late afternoon, at the Sanderson Motel. Clearwater would pick up some “sheets” there—information, leads, suggested marks. He had a route that took him throughout the South, like any other traveling businessman.

“I need to do some work in town,” said Clearwater. “You go on in and get a room. It’s best if I don’t appear to be traveling with anybody. I can explain at breakfast. Right over there at Mae’s.” Mae’s had a big yellow sign on top of a small café. “I have a job available you might want. I’ll see you over there at seven-thirty?”

“Yes sir.”

Blinky, from his cover—the Johnson and Ball Company in McNeill—provided the sheets. Most of his leads required reconnaissance, some required planning, and all thefts were to be reported.

Clearwater researched and planned carefully. During the next day or two he’d find a mark, make maps, decide alibis, and plan exactly how to use his new associate, if the boy took the job. An associate would certainly reduce his chances of getting caught.

The motel clerk, a little man with thick glasses, gave Henry a key and a flyswatter. On the counter was a wire display rack holding postcards, a color photograph of the motel on the front of each. Henry bought two. Displayed under a glass countertop were necklaces, rings, and packs of exotic cards.

“How much is a pack of those cards?”

“Twenty-five cents. I got some under the counter for fifty cents. Want to take a look?”

“Maybe tomorrow. I’ll take that twenty-five-cent pack, though.”

In his room, Henry put his suitcase in a corner and his valise on the bed. An electric lamp made from an oil lamp stood on a chest of drawers beside a radio. He noticed three cigarette burns along the edge of the chest top. Some burns had been sanded off, it looked like. He hung his suit and his sport coat on a wire hanger in the small closet, took off his shirt and undershirt and dropped them in a corner. He’d wash them in the tub, do some ironing if they had an iron in the office. He looked in each dresser drawer. Top: empty. Middle: a book of matches. He pocketed it. Bottom: empty.

This prospect with Mr. Clearwater could get him into something a little higher up—well, not out of Bible selling altogether; he didn’t want that. He could keep selling Bibles on weekends, at least.

A full-length mirror leaned against the wall beside the dresser, bottom left corner broken off. He dropped his boxer shorts, kicked them into the corner, turned sideways, drew in his stomach, expanded his chest, clinched his fist, hardened his arm muscles. He turned and faced the mirror, crossed his arms. He turned his head left, right. Checked his hangings. They always looked bigger in a mirror than when you looked down.

He stopped up the tub drain with the chained stopper and let the water run longer than he ever did at home. Aunt Dorie let him use only just enough water to reach the back of the tub. He stepped in and sat slowly. The water was hot. It had been almost two weeks since he’d had a shower at a barbershop. He slid down so his head rested against the back of the tub and closed his eyes. He thought about this possible new job. Mr. Clearwater looked like he made a lot of money.

He wet and then soaped his head, neck, arms, under his arms, his chest and back, pushed his midsection up out of the water, soaped his hangings and the crack of his ass. He then slid down into the water, pushing his knees up, splashed water over his chest. He stuck fingers in his ears, dropped his head back into the water, held it there and shook it to rinse his hair. He sat up. The water was gray. He splashed water over himself some more, stood, stepped out onto a small, round rug, dried himself with the towel, wrapped it around his waist, walked back to the standing mirror, and looked at himself again.

He dressed in clean clothes from his suitcase. The white shirt was wrinkled, but the pants weren’t too bad. He buckled his belt. He found his long black comb in the inside flap of his suitcase and combed his hair back while standing in front of the full-length mirror. Back at the sink he wet the washcloth, wrung it out, and smoothed down his hair. Like Uncle Jack.

What kind of job might it be? Anybody driving a new Chrysler could probably pay a good salary—or worked for somebody who could.

It was four o’clock, not too late to sell a Bible or two and maybe get invited somewhere for supper. He walked north along the road to a row of houses he’d seen from the motel office. He carried his valise and, in his head, lessons from Mr. Fletcher.

My job is to teach you how to sell Bibles, gentlemen. Period. End of story. From an economic point of view there are two and only two sides to every customer encounter: making the sale or not making the sale. Economics is the invisible hand that moves the world. So: two sides—the head, the tail; a sale, no sale. Kaput. The end. And you will squeeze every opportunity out of every moment of every customer encounter to make that sale. So now, gentlemen. Let’s start by writing down a definition of Bible selling.

Bible selling . . . is the act . . . of getting customers . . . to behave in ways . . . assumed . . . to lead to . . . Bible buying. Bible selling is the act of getting customers to behave in ways assumed to lead to Bible buying.

Let’s all read it together now, and then you’ll memorize it, and I can promise you it will be one of the last statements you remember as you pass from this mortal realm into the next.

Bible selling is the act of

. . .

He walked past three houses that didn’t look inviting—dirt yards. Except one of the yards was raked. Next, after a short stretch of woods, three houses with lawns and shrubs sat back a ways from the road. He checked in his valise to be sure the Bibles were arranged, pulled out the box containing a Bible, walked up and knocked on the screen door. He heard steps. The inside door opened and a woman stood holding a cooking pot and a drying rag.

“How do you do, ma’am? My name is Henry Dampier, and I have a little something in this box that is mighty nice that I’d like to show you if you don’t mind. It’s something I think you might like—if I could step inside for a minute, maybe.”

“I appreciate it, but I ain’t interested in buying nothing today. My cat died this morning. I’m behind on everything. I just got to washing and drying my dinner dishes.”

“Oh, mercy. That cat was probably just like a member of the family.”

“She was. She sure was.” The woman stood without moving, not much life in her face, her eyes.

You do

not

want to keep standing out there on the porch with the screen door between y’all. You want to get inside, and you do that by looking and talking in ways to make her like you in about ten seconds—that’s all you got.

“Oh Lord,” said Henry. “I remember when we buried Trixie, my uncle’s dog. It was all tears around the house when Trixie died. My sister especially. What was your cat’s name, ma’am?”

“Bunny. I called her Bunny Rabbit.”

He saw that her hand which had been against the door screen was still there. “I’m awful sorry. Did I introduce myself?” It was a matter of seconds now.

“You did, but I done forgot your name.”

“Henry Dampier, ma’am. I tell you what, ma’am. Have you buried Bunny yet?”

“No, I ain’t been able to bring myself to do it. Burt—Burt’s my husband—he’ll do it when he gets home.”

“I was going to offer to say a little prayer at Bunny’s grave.”

Sometimes, gentlemen, you’ll need to improvise. Jazz musicians do that when they put new notes where a melody used to be. They get off the beaten path, but brilliantwise.

“I’d be happy,” said Henry, “just to step around back and bury her, if you got a shovel. I’m very partial to cats.”

“Oh, that would be real nice, Mr. Dampier.” She stepped out onto the porch. “I been here by myself, and I just couldn’t bring myself to do it, so I was going to wait until Burt got home. Bunny’s under the back steps.” They were slowly moving toward the porch steps.

“If you want to,” said Henry, “you can stay in the house and I’ll do it, if you’ll tell me a good place for a grave. I don’t believe I got your name—not that I really need to, but it’s always—”

“I’m Martha Kelly.” She reached out her hand, and Henry took it. “Well, that would be real nice,” she said. “You can see her rear end out from under the steps. I just couldn’t bring myself to . . . She’s over fifteen years old. Anywhere out in the edge of the woods would be good—straight back beyond the middle apple tree back there. The shovel is leaning against the back of the house. Lord, it’s been a blue, blue day. She was like a, well, like a child. Just . . . just knock on the back door when you’re finished. Oh my goodness. Poor Bunny. Poor Bunny.”

“I’ll just leave my valise right here on the porch,” said Henry, “and my little box.”

I’m here to tell you that there is one thing more important than sickness and health, life and death, love and war, food and water, and that is the sale. The sale. Understand that, if you want to sell a lot of Bibles. And you’re hanging on to that possibility that you are leading her in the direction of her own behavior that’s going to lead to her buying a Bible, and you won’t turn loose without a sale, see, until you see clearly that you risk either getting killed or embarrassing yourself into stupidity.

“What are you selling?”

“I’m selling Bibles, ma’am. God’s holy word.”

Bunny’s rear end was like she said: out from under the steps. Yellow. Henry couldn’t see her head. He grabbed both back feet and pulled so she’d slide out. First he noticed the head was swollen way, way up. It was gigantic. Then he saw a . . . a snake—“Oh my gosh.” He turned the cat loose and stepped back. The snake was hanging from her mouth, not moving—clearly dead too. “Oh my gosh.” It was a copperhead, a small one. He squatted to examine. Somehow the snake’s head . . . He looked around, picked up a rock and a short stick, wedged them into Bunny’s mouth. Her front right big tooth was through the middle of the snake’s head, and the snake’s fangs were in Bunny’s—what?—lip, which was twisted somehow. Oh my goodness, get them buried before the lady sees, he thought. She would die. That head was big as . . . big as a cantaloupe.

He looked into the neighbors’ backyards. Nobody out there to see. He got the shovel underneath Bunny’s midsection, lifted her—she was stiffening—and with the snake dangling, he started to the woods, his body between Bunny and the back door of the house. The snake, a little less than two feet long, held.

Just inside the tree line, beyond the middle apple tree, he lowered Bunny and the snake to the ground, dug a hole about two feet deep and plenty long—it was nice soft topsoil, no clay—and buried them. He patted the pile of dirt with the shovel. He thought about a cross, looked around for a big rock, found one, placed it at the head of the grave. That was one awful-looking cat head. Poor Bunny.

He stepped out of the woods and saw Mrs. Kelly coming, from just beyond the apple tree. As they met, he saw that her eyes were red.

“I can’t tell you how much I appreciate this, Mr. Dampier.” She held a tissue in her hand. “She hadn’t been hit by a car, had she?”

“Oh no. No ma’am.”

“When I went out to put water in her pan I saw her poor rear end and called and she didn’t move, and I knew in my heart that that was the end. I think she died in her sleep, peacefully.”

“Yes ma’am. That’s what it was. That’s what it looked like.”

“I was worried she might, you know, have been hurt somehow.” She looked over his shoulder toward the grave. “I lost my brother, Walter, in the war, and I haven’t been able to deal with things very well since then. I have these nightmares. He was my only brother and . . . Were her eyes closed? That’s one thing I always worry about.”

“Oh yes ma’am. They were real closed.”

“Would you show me the grave—walk with me out there?”

“Be glad to.”

They stood at the foot of the grave. Henry tried to think of something to say. “I’ll say a little prayer if you like,” he said.

“Oh, that would be nice,” said Mrs. Kelly.

They bowed their heads. Henry prayed, “Dear Lord, for the long life of Bunny we are grateful, and surely goodness and mercy has followed her all the days of her long life, and now she shall dwell in the house . . . or close to the house of the Lord forever. Amen.”

“Amen,” said Mrs. Kelly. “I always heard animals don’t go to heaven,” she said. “I was a Catholic when I was growing up, and that’s what I always heard.”

“That’s what I always heard too, and I’m a Baptist, so I said ‘close to’ instead of ‘in’ for some reason. I don’t know. It’s . . . you never know.” Henry started moving away from the grave, back toward the house—he took a step or two.

But Mrs. Kelly stayed put. “I been thinking I ought to of had her buried in something,” she said.

“You mean . . . you mean like a dress?” asked Henry. He saw a little dress with that giant head sticking up out of it. Bunny would need a man’s hat.

“Oh no, like a shoe box or something. I just don’t . . . I could get the box Burt’s work boots come in. That hard cardboard would be fine to keep the dirt off her.”

“You want to rebury her?”

“Yes.” She looked up at Henry. “If you would. I want to see her again, one last time. I should have at least looked at her. I never got to see Walter. He had some kind of head injury, and none of us got to see him.” She brought her tissue up to her eye. Then she started crying for sure and dropped to one knee. “Oh, Bunny. My beautiful Bunny.”

Henry, holding the shovel, eyed the back of her house, where’d he’d planned to set the shovel back. He stood still, feeling some heat around his neck. Maybe he could sing something. My Bunny lies over the ocean? My Bunny lies over the sea? “I remember Trixie,” he said, “this dog my uncle had. We just dropped her in a big hole and then threw the dirt in right on top of her. Never thought about a box. I think just plain dirt is the more or less normal way for an animal.”

Mrs. Kelly, sniffing, said, “It’s not too deep, is it? It wouldn’t be a great bother to dig her back up, would it?”

“Oh, well, no, no ma’am. It’s not too deep.”

“If you don’t mind,” said Mrs. Kelly. “I’ll go get the shoe box.” She stood and started for the house.

Henry looked at the grave. No choice now. He started digging. Something would come to him. Improvise. He lifted Bunny on the shovel out of the grave. If I get rid of the snake maybe I can make up something, he thought. He thought about her brother, Walter. He looked toward the house. Mrs. Kelly was coming down the back steps with the box. He didn’t want to get venom on his hand. He pulled out his handkerchief and, using it as a glove, pried Bunny’s mouth open, pulled the snake’s head off the tooth, looked up at Mrs. Kelly, her head down. She was almost to the apple tree. He flung the snake. The cat’s head was enormous, the lips misshapen and bloody at the snake bite. The eyes—where in hell were the eyes? He tied his handkerchief around Bunny’s head. He arranged the cloth, tucked.

Mrs. Kelly was standing there with the box.

“I’m just arranging a burial shroud,” he said. “It’s the way they bury all cats in England nowadays. I was just reading about it. It’s a custom over there. Catching on here. I’ve done a few before.”

“Her head looks swolled up.”

“Oh no ma’am. That’s from the way I arranged the handkerchief. Let me see that box. Poor thing.” He almost snatched the box and, moving fast, put himself between Mrs. Kelly and Bunny, slipped Bunny in the box headfirst, shut the lid, and said, “Let’s close our eyes in prayer. Our Heavenly Father, as we gather here, let us realize that Bunny has paid the final price, has reached her final destination, her final resting place”—he had one eye open and was moving the box into the hole with his foot—“and is now prepared for the kind of privacy that comes to all of us who have breathed our last breath after a faithful time of service of loving our masters, amen, and now I’m just going to pick up the shovel and cover her up with some mother earth and—”

“Her head looked swolled up to me.”

“Oh no ma’am, it was the way you tuck a burial shroud that made it look that way. It’s a kind of protection. It’s called a burial tuck.” Henry shoveled dirt onto the box. It made a sound like hard rain, and then the box was out of sight. If she said to uncover it, he would have to just walk off, he figured. Tell her he had to be somewhere.

“I can’t thank you enough, Mr. Dampier,” she said. “Burt will be home about suppertime. If you’ll come back by, I’m sure he’ll want to buy a Bible.”

“I need to get on now, Mrs. Kelly, and what I’m going to do is give you a, a couple of Bibles. You’ve been through a lot today. I like to give away a complimentary Bible now and then, and I think you deserve a couple. Let’s go pick them out.” He patted the top of Bunny’s grave a few times with the shovel, leaving imprints.

Back at the motel Henry noticed that Mr. Clearwater’s car was gone. He ate supper across the street at Mae’s—a patty of ground beef with mashed potatoes, biscuits, and string beans. Back in his motel room, he undressed and put on his pajamas. He knelt by his bed and prayed. “Dear God, help me to make the right decision in all I decide to do. Guide and direct me in the right path, oh God. In Jesus’ name. Amen.” He thought about Bunny, that head.

He sat on his bed and opened his Bible to Genesis. He read again, kind of fast, the first two chapters, then went back to the places he’d underlined. Aunt Dorie used to underline a lot in her Bible.

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

Then God made light, Henry read, and heaven, and earth, and plants by the third day. Then he made the seasons and sun and moon and stars on the fourth day. Then he made all the animals and creatures on the fifth day. He’d underlined “all the animals” and “fifth.” He kept reading:

And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

So

God created man in his own image,

in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them. And God blessed them. . . .

And the evening and the morning were the sixth day.

Thus the heavens and the earth were finished.

So it was the sun, then animals, then people. But then later, in Genesis 2:

And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed. . . .

And the Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him.

And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them.

First way: animals, then people. Second way: people, then animals.

Nobody had ever talked to him about two completely different orders. Why? It almost hurt him to think about it—how could anybody read that and not talk their head off about it? One version, but not both, could be right. One was wrong. And the Bible was supposed to be right all the way through.

And then there was that other thing, where he had stopped reading a few nights earlier. As plain as the nose on your face, in Genesis 6:

And it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them,

That the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose.

He saw these sons of God walking around on earth marrying the daughters of earth men. But Jesus was supposed to have been the only begotten son of God. “Dear God,” he prayed again. “Help me to understand thy word. Guide and direct me.” These verses were clear. Plain English. Second Timothy 3:16 said, “All scripture is given by inspiration of God.”

The next morning Henry and Clearwater sat across from each other, eating breakfast at a table in Mae’s Café. Henry told him about the cat. But he kept it short. “My Bible-selling teacher talked to us a lot about selling Bibles, and I had to keep thinking what he said about ‘improvise.’” He wanted Mr. Clearwater to bring up the job thing, so he’d keep quiet about all that in Genesis—for the time being, anyway. He dipped the corner of his toast into his mixed-together eggs and grits.

“Okay,” said Mr. Clearwater. He wiped his mouth with his napkin. “This job. It’s not the kind of business I can tell just anybody about. I work for the FBI.” He pulled out his billfold and opened it. A badge. He was a G-man! “We infiltrated a gang of car thieves about six months ago,” he said. “They work from here to California, mostly in the southern part of the United States, and then all up and down California. They steal a car—hot-wire it, normally—get it painted unless it’s black, an ignition system installed, and then they might sell it, or drive it to California, or turn it over to somebody else, whatever. I get the ones that they’re selling, usually. Hadn’t had to drive anything to California yet. And what I need is a driver, because that’s my Chrysler out there, and sometimes I’m dealing with two cars at a time, and even when I’ve got just one car, I like to have somebody driving for me.”

“So you know J. Edgar Hoover—you’re a actual G-man?” This was far better than Henry could have imagined.

“Oh yes. J. Edgar and me are pretty good buddies. I’ve shot pool with him, eat supper with him, but he don’t let nobody know that he shoots pool, see. He’s a Christian, like you . . . and me.”

“I’ll take it. It sounds like a good job.” He wished he could tell Uncle Jack. Aunt Dorie would be afraid, though.

Clearwater extended his hand. “Good. We’ll start tomorrow. I think we’ll have a pickup tomorrow afternoon. Be ready at three o’clock to leave here in the Chrysler and meet me at a place I’ll draw out for you on a map. And in a few months from now, when everything is lined up, we’ll be making a big number of arrests, all on the same day. All you’ll have to do in the meantime is drive for me. You’ll make more money than you do selling Bibles, I can tell you that. Twenty-five dollars for every car we move, and that’ll be, oh, up to three or four a week.”

Henry’s mind went: A hundred dollars in a week.

“Then some days we just sit,” said Clearwater. “It’s kind of off and on.”

Henry looked around at other people eating breakfast. They were so normal. Nothing like this going on in their lives. They were farmers and regular people. “Can I keep selling Bibles?”

“As long as we’re clear about when you go out and when you get back. I need you on call, more or less.”

“Am I supposed to dress up like you?”

“Not necessarily. You might get a hat or some hair oil and put the end of your belt where it belongs.”

“What’s a pickup?”

“I said you might get a hat or some hair oil and use your belt loops.”

“Sure. Yes sir.”

“A pickup is a car delivery. Somebody will deliver me a car. And another thing: You don’t ever, under any circumstances, tell anybody what you’re doing. In fact, you have to take an oath. We’ll do it on one of your Bibles before our first gig. If you do tell somebody, it could cause the whole FBI undercover department to fall apart.”

“Okay.”

“I’ll be getting coded messages—general delivery—here and there, and messages at certain motels. This one, for example. I don’t actually do the stealing, normally, though I have been asked to do that once or twice. They deliver me a car to drive somewhere, or to get painted, and then we’ll do it all over again. You’ll be waiting for me somewhere, I get the pickup and drive it to you. All you do is drive. And if you ever by chance get arrested and I’m not around, then all you have to say is ‘Code Mercury,’ and then your name and my name, Preston Clearwater. No matter what they do or ask you, or how many times, that’s all you have to say.”

“Do these car thieves ever kill anybody?” asked Henry.

“You don’t ever know with these types.” Clearwater motioned for the waitress.

“It don’t sound too dangerous, though. Just driving.”

“It’s not at all dangerous. I’ll get this breakfast. You can pay your part when we eat from here on out.”

Henry was astonished that he could make so much money doing anything, especially while gaining a kind of glory. It sounded like a comic book adventure, or something from the movies. He’d be serving God in a different way. Good against evil. He remembered the pictures in Aunt Dorie’s Children’s Book of Bible Stories: David facing the giant, Goliath, and then the picture of him about to cut Goliath’s head off; he saw the picture of Jesus and the money changers—of Jesus chasing them away from the temple. He’d be dealing with bad people. He’d be righting wrong in a way he’d never dreamed of. Parts of the Bible had to do with all this, parts about the Pharisees, and Babylonians, and Roman soldiers, with sin and evil, and good—and all that was true, for sure—and all of that is what he would be a part of, in modern times. He’d probably figure out these Genesis things. He was going to go ahead and read past Genesis 6, anyway, just to see if there were more confusions. This was way back when maybe things got a little mixed up, before people could read and write, when all they could do was tell things.

Clearwater felt like he’d stumbled onto a gift. This boy had some enthusiasm, some energy, and as long as he kept him the right distance from the action—in the dark, that is—he’d be able to work Blinky’s route on down into Georgia and Florida, and then back up into the Carolinas, where they could visit some mill bosses, some big tobacco men, relieve them of a few fine cars. He’d gotten a raise on the cars from twenty-five percent to forty percent, and if he didn’t get caught or otherwise mess up, then by the time he met with Blinky again, his two-year road quota would be made and he’d be able to move up into more advanced jobs.

That night Henry continued reading in Genesis. About Abraham and Sarah, when their names were Abram and Sarai. He hadn’t known about a name change until he jumped ahead and figured it out. But when he jumped ahead he found out about Abraham saying for some reason that his wife Sarah was his sister. He had forgotten that Abraham had a wife, then he remembered: they’d had a baby when they were real old. And he certainly had never heard about what he read in Genesis 16, and then reread.

Now Sarai, Abram’s wife, bare him no children: and she had an handmaid, an Egyptian, whose name was Hagar.

And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing: I pray thee, go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram harkened to the voice of Sarai.

Henry saw that “go in unto” meant go to bed with her and have a sex relation. It was as plain as day. He kept reading. Abraham did it. God wrote it and didn’t worry a whiff about it, not a whiff. Nobody was bothered by it.

Something was wrong. The God that wrote this was not the God he’d been taught to pray to.

Why should he not have a sex relation or two before he was married? Outside of marriage, like Abraham.

He kept reading, skipping around, past Joseph’s coat of many colors and his brothers and the hidden cup. He’d heard all that. Then he read in Genesis 38 about a woman named Tamar, and when he finished that one he had to put down his Bible and walk outside and look up at the sky and say, “What in the world?”

So that more or less settled that. He wouldn’t have to wait until he got married. Why shouldn’t he do what they were doing in the very Bible—the good guys, with no consequences? Else the consequences would be mentioned, because God would want them mentioned.

It was three a.m. and he needed to go to sleep. He didn’t know what to pray.

Mr. Sim Simpson Beaten, New Car Stolen

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C.—Clarence “Sim” Simpson reported yesterday that he was assaulted by a stranger and his DeSoto automobile was stolen and driven away, leaving him helpless and injured on the ground in the parking lot behind Clark’s Furniture Store just south of town. Simpson was carried by bystanders to Leeds Hospital and released after treatment for a skull fracture.

Mr. Simpson is a retired Army master sergeant and now owns several grocery stores in the area.

Simpson reported that his car was taken in broad daylight by a man with long black hair, wearing a derby hat and sunglasses. The man was alone, seated in Simpson’s car, and claimed the car was his when Simpson approached him. Simpson said the man must have hot-wired the DeSoto while Simpson was buying a sofa in Clark’s Furniture Store.

“I thought he’d made a normal mistake and got in the wrong car,” said the injured Simpson. “And when he picked up a crow bar out of the floor board, I couldn’t imagine what it was for. Next thing I knew I was flat on my back.”

A witness, Ned Seagroves, reported that the car headed south on County Highway.

Excerpted from The Bible Salesman © Copyright 2012 by Clyde Edgerton. Reprinted with permission by Back Bay Books. All rights reserved.

The Bible Salesman

- paperback: 272 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316117579

- ISBN-13: 9780316117579