Excerpt

Excerpt

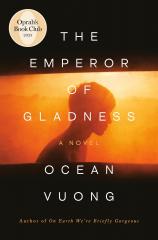

The Emperor of Gladness

“Come in. But take off your shoes. My husband put down these floors.” The woman disappeared into the house. The boy hesitated, looking down the empty street. The rain was picking up again. He stepped onto the porch, water running off him in rivulets, took off his boots, and followed her inside.

A creaky rail house built by freight workers over a century ago, the home was one large hallway divided into three rooms: a parlor, a dining room, and a kitchen, whose dim light now glowed at the far end like the hearth of an ancient cave. Furnished in a style the boy had seen only in the black-and-white TV series Lassie, whose reruns he watched on a three-channel Panasonic as a kid, the house had the stuffy odor of rooms whose windows rarely opened undercut with the mildewy rank of crawl spaces. As his eyes adjusted, amorphous furniture upholstered in sprawling pale florals came to view. The walls were wood-paneled and adorned with cheap landscape paintings in gilded frames. As he passed the transom that divided the parlor from the dining room, he looked up and saw what was once a white cross, now phantom-grey from decades of dust. On one wall, lit by streetlights, a cluster of grim-faced portraits stared out from an era he couldn’t locate. He paused at the kitchen’s threshold, water falling from his chin and hair on the laminate floor.

The woman sat down at a small table and nodded toward an empty chair. “Go on, sit. You look like a dunked cookie.”

He sat carefully, his eyes taking in the room. Not knowing what to do with his hands, the boy placed them, palms up, on the table but withdrew them to his lap when he realized this looked psychotic.

“Here, dry yourself.” She handed him a dish towel. It smelled of raw onions but he wiped his face anyway, his eyes quickly stinging.

“Poor kid,” she mumbled to herself. “Hey, it’s all over now, okay? Whatever happened is over. But don’t you cry, boy. Tears deplete your iron, you know.” She grabbed the rag, leaned over and dabbed his eyes some more, deepening the burn. He winced and turned away. “Okay, you’re not a boy. You’re a man and don’t need nobody to wipe your tears.”

The kitchen was the size of a large shed and contained a stovetop browned with grime-stuck grease, a sink, and a portion of countertop the size of a cutting board. They sat at a round table covered in plaid plastic meant to look like picnic cloth. From its center, a fabric-shaded lamp trimmed with tulle emitted a sickly amber glow.

She grabbed a nearby pack of cigarettes, a brand he didn’t recognize, slipped one between her lips, and put a lighter to it. “I normally don’t smoke.” She took a drag and stared at him, not unkindly, then leaned over and pushed aside a large stack of magazines. They were decades old and printed in a language he couldn’t make out.

“Lithuanian,” she said, clocking his curiosity. “Know what that is?”

He shook his head, wiping the onion tears from his cheeks.

“An old country, far away, where I was born.” She waved the cigarette about and took a drag. “But all countries are old, if you think about it.”

But he had never thought about it. He had rarely thought about any country, least of all the one he was born in—only that it, too, was far away.

“Want one?” She handed him a cigarette.

Before he could answer she placed it in his mouth and lit it.

“You like my owls?” She pointed over her shoulder where an armoire loomed behind her. Behind its glass doors was a fleet of owl figurines of many shapes and sizes, some porcelain and shining, others the matte of wood or clay. “Every owl was made in a free country. None of my owls,” she leaned back, “came from Communists. Understand?”

He lied by nodding.

Above the armoire were three paintings of owl portraits, their faces bloated as old mobsters, each one depicting, like a Rembrandt study, a new angle to the bird’s face. In fact, owl knickknacks, tchotchkes, and icons stared at him from nearly every surface. “I collect them. Don’t know why really,” she shrugged. “People started giving them to me long ago. Now it’s my calling card.” She smiled weakly through the smoke. “What’s your name anyway?”

“Thanks for this.” The boy took a long drag from the bogie. “But I should go.”

“Easy, little lamb. I invite you in my home, give you cigarette. And look,” she tilted the pack to show him, “I only have two left. I even let you cry in my kitchen. You know it’s bad luck to cry in the kitchen, right? You can at least tell me your name.”

He stared at the plastic coverlet on the table pocked with holes and considered the name his mother gave him, the thought of it sinking him. It wasn’t that he didn’t like his name—only that he had been willing to toss it in the river. He had never wanted to throw his name out, just the breath attached to it. The name, after all, was the only thing his mother gave him that he was able to keep without destroying.

“Hai,” he mumbled.

“And hello to you too. But—”

“No, Hai. It’s—”

“Okay,” she breathed, “but who am I saying hello to?”

“My name is Hai.”

“Your name is Hello?”

He decided to nod. “Sure.”

“Ah.” She brightened and pointed a crooked finger at him. “So your name is Labas!”

“What?”

“Labas means ‘hello’ in my country.” She extended her hand across the table for him to shake.

“Hello, Labas. I’m Grazina. Means ‘beautiful.’” She grinned, the cigarette smoldering through her yellow teeth.

He shook her hand, cracked dry and warm. “Hello.”

Excerpted from THE EMPEROR OF GLADNESS by Ocean Vuong. Copyright © 2025 by Ocean Vuong. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Emperor of Gladness

- Genres: Fiction

- hardcover: 416 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Press

- ISBN-10: 059383187X

- ISBN-13: 9780593831878