Excerpt

Excerpt

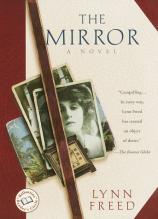

The Mirror

Chapter 1

1920

I came into that house of sickness just after the Great War, as a girl of seventeen. They were there waiting for me, father and daughter, like a pair of birds, with their long noses and their great black eyes. The girl was a slip of a thing, no more than twelve, but she spoke up for the father in a loud, deep voice. Can you do this, Agnes? Have you ever done that? And the old man sat in his armchair with his watch chain and his penny spectacles, his pipe in his mouth and the little black moustache. Sometimes he said something to the girl in their own language, and then she would start up again. Agnes, do you know how to--

The wife was dying in the front parlor. They had moved a bed in there for her, and they kept the curtains drawn. In the lamplight, she looked a bit like a Red Indian, everything wide about her--eyes, mouth, nostrils, cheekbones. Even the hair was parted in the middle and pulled back into a plait.

From the start, she couldn't stand the sight of me. She would ring her little bell, and then, if I came in, give out one of her coughs, drawing the lips back from the raw gums to spit. And if that didn't do the trick, she growled and clawed her hands. So I had to call the native girl to go in and put her on the pot or whatever it was she wanted this time. I didn't mind. I hadn't come all this way to empty potties. They'd hired me as a housekeeper, and if the old woman was going to claw and spit every time I entered the room, well soon she would be dead and I'd still be a housekeeper.

They gave me a little room on the third floor, very hot in the hot season, but it had a basin in it, and a lovely view of the racecourse. Every Saturday afternoon, I would watch the races from that window, the natives swarming in through their entrance, and the rickshaws, and then the Europeans in their hats, with their motorcars and drivers waiting. After a while, I even knew which horse was coming in, although I could only see the far stretch. But I never went down myself, even though Saturday was my day off, and I never laid a bet.

I kept my money in a purse around my neck, day and night. I didn't trust the natives, and I didn't trust the old man I worked for. Every week, he counted out the shillings into my palm, and one before the last he would always look up into my face with a smile to see if I knew he had stopped too soon. The daughter told me it was a little game he played. But I never saw him play it on the natives. There were two of them, male and female, and they lived in a corrugated iron shack in the garden. My job was to tell them what to do, and to see they didn't mix up dishes for fish and dishes for meat, which they did all the time regardless.

It was the daughter who had recited the rules of the kitchen for me, delivering the whole palaver in that voice of hers, oh Lord! And once, when there was butter left on the table and the meat was being carved, it was she who called me in and held out the butter dish as if it had bitten her on the nose. And the old man, with his serviette tucked into his collar, set down the carving knife and put a hand on her arm, and said, Sarah. So Sarah shut up.

There were other children, too, but they were grown up and married. Some of the grandchildren were older than this Sarah, older than me too. One of the grandsons fancied me. He was about my age, taller than the rest, and he had blue eyes and a lovely smile. But I hadn't come all the way out to South Africa to give pleasure to a Jewboy, even a charmer. I meant to make a marriage of my own, with a house and a servant, too.

And then, one day, the old man sent up a mirror for my room, and I stood it across one corner. It was tall and oval, and fixed to a frame so that I could change the angle of it by a screw on either side. And for the first time ever I could look at myself all at once, and there I was, tall and beautiful, and there I took to standing on a Saturday afternoon, naked in the heat, shameless before myself and the Lord.

Perhaps the old man knew. When I came into the room now, he would look up from his newspaper and smile at me if Sarah wasn't there. And under his gaze, it was as if we were switched around, he and I, and he were the mirror somehow, and I were he looking at myself and knowing what there was to see, the arms and the legs, the breasts and the thighs, the hair between them. And in this way I became a hopeless wanton through the old man's eyes, in love with myself and the look of myself. I couldn't help it. I smiled back.

And then, one Saturday afternoon, he knocked at my door and I opened it, and in he came as if we had it all arranged, and he went straight over to the mirror and looked at me through it. I looked, too, a head taller than he was, bigger in bone, and not one bit ashamed to be naked.

The first thing he did was to examine the purse around my neck, which I always wore, even in front of the mirror. He fingered it and smiled, and looked up into my face. I thought he might try to open it and start up one of his games, but he didn't. He left it where it was and put his hands on my waist, ran them up to my breasts and put his face into the middle of them. And then he took them one at a time, and used his lips and his tongue and the edge of his teeth, and all this silently except for the jangle of my purse and the roar of the races outside. And, somehow, he unbuttoned himself and had his clothes off and folded on the chair without ever letting me go. And we were in and out of the mirror until he edged me to the bed and there we were, in the heat, under the sloping ceiling, the old man and me, me and me, and I never once thought of saying I wasn't that sort of girl. And when he had gone and I found a pound note on the table, I didn't think so then, either. Money was what there was between us. I was hired as a housekeeper. And he had given me my mirror.

She found out about it, of course, the old cow downstairs. I heard her coughing out her curses at him, whining and weeping. But he didn't say much. And when Sarah came to find me in the kitchen parlor and announced in that voice of hers that I was never to go into her mother's room again, who did she think she was punishing?

Still, I felt sorry for Sarah, ugly little thing, flat in the chest, with the thin arms and the yellow skin, and a little moustache on the upper lip. I would have told her how to bleach it, but she wouldn't look at me now. Nor would she look at her father. She sat at the table with her eyes fiercely on the food, saying nothing at all. It was only to her mother that she would speak willingly, rushing into the front parlor when she came home from school, performing her recitations there, as if the old woman could understand a word of them.

For me, the house was separated in another way--up there, where it was airy and he came to kneel before me in silence, and down here the dark sickness, the smells of their food and the sounds of their language, the natives mooching around underfoot.

And meanwhile, my money mounted up. The old man kept to the habit of leaving some for me every time. Not always a pound, but never less than two and six. After a while, there was far too much to fit into the purse, so I hid the notes in a place I had found between the mirror and the wooden backing of it, and the larger coins inside the stuffing of my pillow. And, one Wednesday, when I had the afternoon off, I took it out of the hiding places and went down to the Building Society and put it in there. But still I wore my purse around my neck, and he loved to notice it there, and to smile as he began to unbutton.

His teeth were brown from the pipe, with jagged edges to them, and his legs and arms were thin and yellow like Sarah's, with black hair curling. But I didn't have to ask myself what it was about his oldness and his ugliness that I waited for so impatiently at my mirror. The younger men, the beautiful young men I saw going to the races, or on my way into town, or even the sons and the grandsons of the household, who were always looking at me now, but not in the same playful way--they would bend me to themselves, these young men, require a certain sort of looking back at them, and a laughing into the future. Oh no.

In the evenings, I brought the old man his sherry on a tray. He drank a lot for a Jew--two or three sherries, and wine, too, when he felt like it. And then once he looked up at me as I put down the tray, and there I was in that moment wondering how I could bear to wait until Saturday, and somehow he knew this because that night he came up the back stairs after Sarah was quiet in her room, and in the candlelight it was even better, the curves and the colors, my foot in his hand, pink in the candlelight as he put it to his cheek, and then held it there as he slid his other hand along the inside of the thigh. And I have never felt so strongly the power of being alive.

And then one Saturday afternoon, I was at the mirror waiting, and the door opened and it was Sarah to say they had called in the doctor, her mother was dying. Except that she didn't get it out because of the sight of me there, naked, with my purse around my neck. And I just smiled at her, because this was my room and she had no business coming in without knocking, and also I liked the look on her face as she gazed at me. And then, as I sauntered to the wardrobe for something to cover myself with, she said, I knocked, but you didn't hear, and she said it so politely for once, and in a normal voice, that I turned and I saw that she was crying, the eyes wide open and staring while the tears found a course around the nose and into the mouth. And she looked so frail, gaping there like a little bird, and she would be so lost now that the cursing old bitch was actually dying, that I went to her, naked as I was, and put my arms around her, and she didn't jump back, but buried her face between my breasts just as her father did, and held me around the waist, snorted and wept against me for a while.

The races are on, I said, to calm her down, and, Shall I dress and come downstairs? But she just held on tighter, and I saw that she was looking at us in the mirror, and there we were, a strange pair hugged together, when he arrived in the doorway behind us, and even so we didn't turn, but stood there, all three of us staring at each other until he said something to her in their language and she sort of melted on the spot, folded down onto the floor in front of me, her hands around my ankles, weeping again. And of course I knew it had happened, the old woman was dead, and that it would change everything, had changed things already. There he stood in my mirror, a tired and ugly old man, muttering something to his youngest daughter. She would take over now, this strange bird at my feet. It was the way it would be, that I knew. And I must get dressed and find my way in the world.

Use of this excerpt from The Mirror by Lynn Freed may be made only for purposes of promoting the book, with no changes, editing or additions whatsoever, and must be accompanied by the following copyright notice: copyright ©1997 by Lynn Freed. All Rights Reserved.

The Mirror

- paperback: 256 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345426894

- ISBN-13: 9780345426895