Excerpt

Excerpt

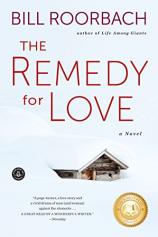

The Remedy for Love

Excerpt:

The young woman ahead of him in line at the Hannaford Superstore was unusually fragrant, smelled like wood smoke and dirty clothes and cough drops or maybe Ben Gay, eucalyptus anyway. She was all but mummified in an enormous coat leaking feathers, some kind of army-issue garment from another era, huge hood pulled over her head. Homeless, obviously, or as homeless as people were in this frosty part of the world—maybe living in an aunt’s garage or on her old roommate’s couch, common around Woodchuck (actually Woodchurch, though the nickname was used more often), population six thousand, more when the college was in session, just your average Maine town, rural and self-sufficient.

Idly, Eric watched her unload her cart: he knew her situation too well. Sooner or later she’d be in trouble, either victim or perpetrator, and sooner or later he or one of seven other local lawyers would be called upon to defend her, or whomever had hurt her, a distasteful task in a world in which no social problem was addressed till it was a disaster, no compensation.

Ten years before, new at the game, he might have had some sympathy, but he’d been burned repeatedly. Always the taste of that Corky Beaulieu kid he’d spoken for and sheltered and finally gotten off light and who’d emptied Eric’s bank account using a stolen check and considerable charm at the friendly local bank, and who’d then proceeded to drive Eric’s first and only brand-new car all the way to Florida before killing that college kid in a bar fight and immolating himself (and the car, of course, total destruction) in a high-speed chase with Orlando’s finest.

Her shopping, pathetic: two large bags tortilla chips, a bag of carrots, a bag of oranges, four big cans baked beans—a good run—but then three boxes of Pop-tarts and innumerable packets of ramen noodles, six boxes generic mac and cheese, two boxes of wine. The one agreeable thing after the produce was coffee, freshly ground, also a sheaf of unbleached coffee filters. Finally, a big bottle of Advil.

Eric turned his attention to Jennifer Aniston on the cover of five different tabloids. Was she aging well? Had she gained a lot of weight? Was a minidress appropriate? Some people in this world got all the attention. Eric noted with odd pleasure that Ms. Aniston was older than he, if not by much.

In a subdued voice, the young woman chose plastic over paper, and the kindly old bagger in his apron and bowtie packed her purchases carefully, well behind the checkout lady’s pace. But good for Hannaford, Eric thought, hiring the guy at no-doubt minimum wage with his savings all eaten up by his wife’s final illness—the sadness of late-life loss was in the old bird’s eyes and posture, even in his hands.

The checkout lady was gruff and impatient, already turning to Eric’s stuff, which probably looked perverse compared with the girl’s, and had come from the new “gourmet” section of the market: organic jalapenos, organic Asian eggplants, organic red bell peppers, a bunch of organic kale for braising, two huge organic onions, a tiny bottle of fine Tuscan olive oil, five pounds good flour, French yeast in cakes, a huge chunk of very, very expensive raw-milk Parmesan (Reggiano, of course), two bottles Cotes du Rhone—and not just any old Cotes du Rhone but Alison’s favorite, thirty-four bucks a pop. Also a packet of Bic razors, the new, good ones with five blades and a silicone-lubricating strip, thick green handles. He was planning to cook for Alison—they’d always had fun making pizzas—and she liked her wine, also his chin, closely shaven, had once bitten him there in passion, but only once, and a long time ago. And fruit: he’d picked out the one ripe mango in the whole display in the event of an Alison morning, unlikely, also a dozen eggs.

The girl druid ahead of him in line wasn’t saying it, but she didn’t have enough money. The old gent had packed everything and placed her six or seven bags of stuff into her cart. She counted out her fives and ones and piles of quarters again. “I thought I had it all added up,” she said humbly.

“People are waiting,” the checkout lady said.

“I’m fine,” Eric said brightly.

The lady behind him made it plural, pleasant voice: “We’re fine.” Back after that, the line was nothing but patience.

“I’ll have to put the coffee back,” the young woman said.

The old gent knew right where the coffee was and dug it out along with the filters, and the checkout lady subtracted them from the register total, apparently a vexing task. Now the young woman’s bill was down to fifty-five dollars and change. She should have gone generic with the Advil, Eric thought. That would have saved her five bucks or more.

“I’ll run ’em back after,” the bagger said, meaning the coffee and the filters. He seemed sadder than ever, and Eric pictured the sweet old fellow using half his break to transport the items back to the correct shelf in some distant corner of the vast store.

“It’s been ground,” the checkout lady said. “You’ll have to keep it.”

“Then the oranges,” the young woman said. “And the carrots.”

She didn’t know but Eric and everyone watching the little drama knew that the oranges and the carrots weren’t going to be enough. He found himself rooting against the Advil: keep the fruit, keep the carrots! That big bottle was probably eleven dollars.

The checkout lady puffed a long breath. But the old gent in the apron said, “No, no, you need your nutrition. I’ll chip in here, honey.”

“I couldn’t,” said the young woman.

“Let’s just take the oranges out, Frank,” said the checkout lady, already tapping the buttons on her register.

But Frank dug in his pockets. “Ach,” he said. He showed the girl, he showed the checkout lady, he showed everyone in line: he only had a dollar and some odd change. Time stood still. Even the motes of dust stopped floating in the fluorescent box-store light. Eric felt something rumbling inside him, rumbling up all the way from his toes, something that gained momentum, something urging him to act, something physical, not articulate at all, something you would have to capitalize if you wrote it down on a yellow legal pad, something you could name a statue atop a fountain in the Vatican, not quite Grace. Charity, perhaps. His hands twitched, his mouth shaped words that wouldn’t come. Finally, just as the girl was going to say something about the Advil, he got it out:

“I’ll get this. Frank, ma’am, young lady, let me get this.”

But Frank had already put his buck-fifty down.

“No,” said the young woman. “No, please.”

Eric added a crisp cash-machine twenty to her pile of wrinkled bills and simple as that, the checkout lady re-added the ticket, gave Eric the change for his twenty, gave Frank back his dollar fifty.

The young woman regarded Eric briefly, coldly, more or less curtsied in that sleeping bag of a coat, flushed further. That was it for thanks. She ducked her head back into the depths of her hood and just pushed her cart out of there, noticeably limping, her very posture humiliated.

“If these people would just learn to add,” the checkout lady said. One was supposed to know what “these people” meant.

Eric’s purchases were already piled in front of old Frank. Eric paid the cashier, more than double the girl’s total, and for nothing but a single evening’s desperate hospitality. Frank, he noted, liked him, cheerfully putting Eric’s stuff in paper bags, two guys who cared about not only indigent young women but about the whole wide world. The checkout lady had no use for them at all, none of them.

#

A huge snowstorm was predicted, first big snow of the season, the inaugural flakes desultorily falling, some kind of unusual confluence of low-pressure and high-pressure and rogue systems, lots of blather on the radio as if a little snow were nuclear warfare or an asteroid bearing down. Eric liked his old Ford Explorer at times like this, even though (as Alison always said) it was a gas pig. He put his groceries in the back, if you could call them groceries, and swung out and across the glazed lot—last week’s ice storm—and there was the young woman, staggering and limping under that mountain of a coat but making determined progress, her seven plastic bags hanging from her arms like dead animals. Eric pulled up beside her but she didn’t stop walking, didn’t look.

“I can give you a lift,” he called.

“Okay,” she said to his surprise, still without looking. He’d expected her to demur in some proud way. He helped her load her stuff next to his in the back and then the two of them got all of his legal folders and books and naked cassette tapes and envelopes and other junk out of her way on the passenger seat, and she climbed in. “Seatbelt,” Eric said.

She buckled up reluctantly.

The Remedy for Love

- Genres: Fiction, Romance, Romantic Suspense, Suspense, Thriller

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Algonquin Books

- ISBN-10: 1616204788

- ISBN-13: 9781616204785