Excerpt

Excerpt

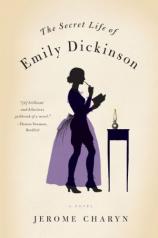

The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson

Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

South Hadley, 1848

Tom the handyman is wading in the snow outside my window in boots a burglar might wear. I cannot see the Tattoo on his arm. It is of a red heart pierced by a blue arrow if memory serves, & if it does not, then I will let Imagination run to folly. But I dreamt of that arm bared, so help me God, dreamt of it many a time. We are not permitted to talk to Tom. Mistress Lyon calls him our own Beast of Burden. She is unkind. Tom the Handyman is no more a beast than I am.

If he lights our stove or repairs the windowsill or bevels the bottom of our door, our vice principal, Rebecca Winslow, has to be in the room with him, & we poor girls have to run to Seminary Hall so that we will be far from Temptation. But I wonder who is the tempter here, Tom or we? There are close to three hundred of us --- if you count the Misses Lyon and Winslow, & our seven Tutors, & Tom, the only male at Mt Holyoke. Heavens, I’d as lief call him Sultan Tom & ourselves his Harem. But Mistress would expel me in a wink dare I whisper that. And Tom is a sultan who depends on crumbs. He lives in the shed behind our domicile, a place so dark & solitary that a cow would die of loneliness were it trapped inside. He cannot come to the table when we dine, but must feed on whatever scraps are left. My room-mate, Cousin Lavinia, sneers at him, says Tom reeks of sweat. She is a Senior & cannot stop thinking of her suitors. Lavinia has hordes of them, the sons of merchant princes & potentates or boys from Amherst College who would love to sneak onto the grounds & serenade their Lavinia, but could not get past Tom & so have sent her half a mountain of Valentines. She is positively engorged with them.

“Cousin,” says she, after cursing Tom, “how many notes from Cupid have you received so far?”

“None.”

“That’s a pity, because I’d opine that a girl hasn’t lived at all until she has a hundred beaux.”

There never was a show-off like Emily Lavinia Norcross. But I’d start a war between our families if I bludgeoned her.

Mistress Lyon summoned us to the assembly hall. She stared at us all, the perpetrators and the innocent parties. “I forbid you to send off those foolish notes. I will not tolerate such frivolities. We do not celebrate Valentine’s Day at Holyoke.” And she promised to dispatch Miss Rebecca to the Post Office to discover if anyone dared challenge her decree. But she did not interfere with the Valentines that kept arriving like missiles, as if any letter that had already been franked were a sacred thing. She wanted our election, and would suffer nothing less. The girls of Mt Holyoke had to avail themselves to be the little brides of Christ, & said brides did not scribble Valentines harum-scarum to the boys of Amherst. The sign of our election was a dreamy gaze into the atmosphere & strict attention to our calisthenics. But I was consigned to Hell, though I had never received nor sent one paltry Valentine. And Lavinia, with her half mountain, was a member of the elect who had discovered God in Mistress Lyon’s sitting room, had prostrated herself & prayed. But my mind would always drift during Devotions, & I’d think of Tom’s Tattoo. Tom had become my Calvary.

Lord, I do not know what love is, yet I am in love with Tom, if love be a blue arrow & a heart that can burn through skin and bone. Tom and I have never spoken. How could we? Mistress Lyon would have him hurled across the grounds if ever he dared address a bride of Christ. Still, I watch him in the snow, sinking into perilous terrain, rising in his burglar’s boots only to sink again & again, as if in the grip of some bad angel who would not leave Poor Tom alone. I pity him caught in the cold without a cup of beef tea. And how can a sinner such as myself help the Handyman? Soon he will start to sneeze & have a monstrous coughing fit & I will wonder if Tom is weak in the lung.

Holyoke does not believe in hired help. We girls make our own beds & have our individual chores. I am the corporal in charge of knives --- no, the animal trainer, since knives are part of my menagerie, like tigers & tigresses, though I never call them such. I distribute the knives during meals & wash them in our sink. Mistress does most of the cooking, & until recently had her own pair of burglar’s boots. But she can no longer do the heaviest chores. Her ailing back will not permit her to collect the trash or repair stovepipes & pump handles. So Tom is on the premises by sufferance alone & Mistress pretends not to see him as much as she can. Pointless to send him notes. Tom does not belong to the population of readers. And no one amongst the faculty will deign converse with our Handyman. Miss Rebecca has taught herself to instruct Tom with a form of sign language & a few gruff shouts. If she wants him to repair the water pump, she performs a little pantomime. She gurgles for a moment, weaves around Tom as if she were a well, then stiffens into pipe or pump handle, & before she’s done, the Handyman has grabbed his tool box & disappeared into that spidery land below the sink.

But there are no Tutors in the snow to interfere with Tom as he rises and sinks like a burglar. I do not have an inkling of why he is out in that little Siberian winter beside Holyoke Hall. The wind is fierce & there is such a howling that the Lord Himself would take cover, though Mistress Lyon might call me a blasphemer for having said so. She, I’m sure, would declare that God can traverse the snow without tall boots. But that still does not explain Tom’s leaping about. Is our Tom constructing his own crooked path for the butcher & grocer? But why would they cross Siberia when there is an open passage to the front gate that Tom shovels every morning at six? Harum-scarum, it is the mystery of Holyoke Hall.

Then I catch the melody of Tom’s design. He is not on a meandering march. He is searching in the snow. He sinks again, & I fear that Siberia has swallowed him until he rises up with a creature in his arms, a baby deer frozen with fright, looking like an ornament on some cradle & not a live thing. It must have wandered far from its family & panicked in the snow. Lord, I cannot see its eyes. But Tom the Handyman keeps the stunned little doe above his head & tosses it into the air as you would a sack. And what seems like an act of consummate cruelty isn’t cruel at all. The little doe unlocks its legs and starts to leap. What a silent ballet before my eyes! A baby deer gliding above the snow, conquering our little Siberia in half a dozen leaps, & disappearing into the forest, while Tom watches until the doe is safe.

I walk about in a vail. no one questions me but Zilpah Marsh.

“Miss Em’ly, why in tarnation are you wearing black?”

“Someone has to mourn Tom,” I say.

“What if Tom don’t need mourning?”

“Well, I haven’t seen him live or dead in a week.”

“That’s because he’s shut up in his shack.”

Zilpah must consider me queer, but I laugh to know that Tom is still among the living. It is a nervous laugh, the laugh of a seventeen-year-old maiden who’s never been courted & kissed by a man.

“Did he fall off the roof?” I ask, frightening myself with my own morbid Imagination.

“Silly creature, Tom don’t climb roofs. He’s shut in, that’s all. He has the grippe, and Mistress won’t let him out of the shack. She fears he might contaminate us all. She’d ship him on the stage to another town, but Tom has nowhere else to go.”

“Where’s he from?”

“Lord knows,” says Zilpah Marsh, as high and mighty as Solomon’s Sheba.

“But Tom isn’t a ghost. He must have his own people somewhere,” I say.

“What people? Tom grew up in Northampton, inside the insane asylum.”

“Zilpah Marsh, I don’t care a bean if you are our monitor. It is most wicked of you to imply that Tom is feebleminded.”

“I said nothing of the sort. The asylum has an orphan’s wing. That’s where Tom was reared. Rebecca told me so. She says Mistress plucked him right out of the orphan’s wing.”

“And what’s his family name if I might be bold enough to ask?”

“Don’t you comprehend my meaning, Miss Em’ly? He’s Tom-of-any-town.”

“I never heard anything so ridiculous in my life. We do not have nameless children in Massachusetts.”

“We most certainly do. The paupers’ association looked after Tom, but they never got around to giving him a proper name.”

I don’t believe a word of it. Northampton Tom. And then I shiver at the appalling truth. Tom was tribeless. Perhaps that was why I seem so soldered to him, as if the two of us wore the same hot bolt. I have all the fruit a name and family can bear, but I might as well have been shaken out of some orphan’s tree.

I couldn’t even tell time until I was fifteen. Father was convinced he had taught me himself, but I just didn’t understand the circling of a clock. I was mortified, like a child caught up in the great mystery of numbers & dials on a replica of the moon’s own round face. But I solved the riddle, saw the dials as the wings of a bird hovering over mountains on the moon with numbers rather than peaks. I could feel in my mind a shadow that the bird left over every numeral, a shadow that darkened as the numbers grew, & thus brought us from breakfast to midnight, round & round again. But it was an orphan’s trick.

I couldn’t leave poor Tom to rot all alone in his shed like the drudge that Mistress imagined him to be. I had to plead with Zilpah Marsh, who could wander wherever she wanted without drawing any suspicion onto her shoulders.

“Zilpah, I have to see Tom.”

“Impossible,” she opines. “Tom is sick as a dog. Missy and I have to wear masks. His bile is all black. I feed him China tea from Missy’s own hospital kit and whatever crusts we have left.”

“What about winter apples and hot potato pie?”

Zilpah scorns me with one of her highfalutin glances. “You are doltish, Miss Em’ly. Mistress wouldn’t waste that kind of grub on a handyman. She’d as lief send him back to the insane asylum in a cart and find another orphan.”

“That’s heartless.”

“Well, child, it’s a heartless world.”

Clever as she is, Zilpah Marsh is no match for a girl who taught herself to tell time by looking for shadows on the moon. I’m loathe to take advantage of her weakness for my brother, the Squire’s son. But Lord, I’ll do anything to get near the Handyman.

“Zilpah,” says Orphan Emily, “my darling brother might be visiting next week.” It’s mostly a lie, but there’s a parcel of truth attached to the word “might.” Zilpah’s ears prick at the mention of my brother. Her eyes grow alert. Her interest in Austin is unbounded.

“Will the young squire be sitting in the parlor with you, Miss Em’ly?”

“Why not? My own brother has to be on the list of male callers. And who would keep him off the grounds? Tom is much too ill.”

“Gracious,” she says, just like one of Mistress’s dowagers. “Would it be much of a burden if you introduced me to the young squire?”

Her face darkens, as if she’s having a dialogue with herself. “Not as the daughter of a chambermaid. I would not want that mentioned. But as your classmate. Will you swear on the Bible not to say a word about my Ma and Pa?”

I pity her mustache all of a sudden, but I still set the trap, even if I’m hellbound in all my wickedness.

“I swear, but you have to do me a favor first.”

Suddenly her eyes are hard as glass.

“I wouldn’t be much of a monitor if I started doing favors for every little nun at Holyoke—what is it you want?”

“Take me to Tom’s shed.”

Lord, punish me for my pride. I have underestimated this stable hand’s daughter. She has much poetry in her blood. She pretends to slap me, touches my face with the tips of her fingers.

“I love the young squire, Miss Em’ly, but you ought not have attempted to bribe me. It belittles you in my estimation.”

My romance had nothing to do with seasons or practical considerations. I likened myself to Mrs. Browning. Not with her beauty, of course, but with her desire to escape an overbearing father and be with the man she loved. Brainard Rowe wasn’t Mr. Browning, and couldn’t afford to take me to Italy. But Daisy don’t need the Florentine. I’d wear a vail and bite back whatever dust the West can bring.

I was in misery over my dog. I couldn’t hide Carlo in a carpetbag—he’s much too grandiose. And the conductors would be mighty suspicious if I tried to board the train with him. They’d brand me as Mr. Dickinson’s daughter. We’d never even get past the terminus at Montague. The railroad detectives would handcuff Brainard and escort me home with my hound. They’d keep my name and Carlo’s from the Republican, out of respect for Father and his relationship to the line.

And so I am a penitent while I pack. Carlo can sense the doom that’s hanging over him. He even manages to get the hair out of his eyes.

It’s a miracle that Brainard reappeared while Father and Mother are in Monson visiting her people. I wouldn’t have had the nerve to steal myself away had Father been around. I walk down from my room with my carpetbag and my dog while Vinnie is dusting the stairs. She’s quick to read that mad determination in my eye.

“Emily, where in damnation are you going?”

“Little Sister, can’t you tell? I’m eloping.”

She drops her duster, removes her apron, and tries to keep calm.

“And who’s the lucky fellah?”

“Domingo --- remember him? That Tutor from Yale.”

“But he vanished from the face of the earth,” Sister says, seeing if she can catch her breath and her bearings.

“I thought you liked him, Lavinia.”

“I did. But what is his current occupation?”

“Cardsharp,” I say.

She’s silent for a second, her eyes gathering up intelligence.

“You can’t be serious. I will not listen.”

“But listen you will. Father will not come one more time with his lantern and drive me out of the Evergreens like household cattle, not while I love a man.”

Sister started to cry. “Will you become a cardsharp’s wife?”

“A cardsharp’s mistress, I imagine. Brainard has not promised to marry me.”

Lavinia’s face went all white. “Then he is a worm, the vilest sort of seducer. He took advantage of your kindness with his sugary talk and convinced you to run away with him.”

“Little Sister, I’m the one who had to sugar him…I will need some hard cash.”

Lavinia is the one who kept the accounts, since Mother could not be trusted with the simplest sum, and I walked around in a daze, with holes in my pockets. But Lavinia could add and subtract like a bank cashier, bargain with the grinder who came to our door to sharpen Mother’s knives, and argue with Mr. Sweetser over the cost of an item on our monthly bill; she kept a purse on a string near her waist, and it was usually fat with three-dollar gold pieces that she dispensed like the Lord’s own bookkeeper.

She must have seen the ravaged look on my freckled face and took some pity. She couldn’t abandon her deranged sister to the wolves. So Lavinia meted out nine three-dollar pieces into the palm of my hand. I barely had the strength to carry them. A neophyte as I was in matters of money, I never realized the heft of a three-dollar coin. I had no purse of my own. And all the pieces did not fit into my pocket.

I reached out to kiss Lavinia, but she was gone, dusting stairs in some far corner, I suppose. It was odd that she did not offer a parting hug, since she might not see me for a century. I had to depend on Little Sister’s good nature, that she would feed and befriend Carlo, who had no friends other than his mistress.

Hair was no hindrance, and I realized for the first time that Carlo only saw what he wanted to see. That dog had a preternatural intuition. He couldn’t take his eyes off my carpetbag. And he must have sensed that it wasn’t his cradle. I was going away and hadn’t provided a proper wagon for him. It was a wound to his dignity.

“Darling, I’d take you if I could.”

Here I am, going to meet my love at the amherst and Belchertown depot, and I can’t stop crying. The sun bakes on my back, and my brains begin to boil under my bonnet. I don’t sniffle once over Pa-pa, who will recover from my exile, my flight into Egypt. Mother hardly exists, and I’ve long ago put her into my box of Phantoms. I wish I could have said my farewells to Austin and Sue, but if I had confided in them, they’d have held me prisoner in the Evergreens until Father arrived with his lantern --- Lord knows, I need a brutal break. Nothing short of that will ever land me in Egypt.

I march down Main Street, past Father’s meadow with its stacks of hay like little mountains of red in the sunlight, past the hat factory, past Rooming-house Row and the “graveyard” it has become ever since the railroad cut through its territories and built a depot. It’s a mystery to me where most of the factory workers and the Irish maids now live. I wouldn’t be startled to learn that some invisible no-man’s-land near the depot had swallowed them up. But I haven’t found it yet, at least not during my late travels with Carlo.

The depot is little more than a wooden hut with a narrow wooden walk and a barn at one end to house and repair broken trains. The tracks that lie between the barn and the hut look like irregular rows of rusty rails that are overrun with grass. A person would have to suffer from blindness or something close to consider the Amherst and Belchertown a thriving enterprise. I’m not sure where the railroad’s capital went. But it didn’t go into building a depot and laying tracks.

People start to collect on that wooden walk for the afternoon run to Springfield and beyond. I begin to fancy that some of them are railroad detectives, though I haven’t the intuition to tease out which ones. There are no immediate neighbors of mine, but I am such a recluse that I wouldn’t have recognized even a half-familiar face. I can still see Carlo with his brown eyes on my carpetbag, and I wouldn’t want strangers to watch me cry.

But forlorn as I am, I can feel that flutter in my heart. And I sing to myself, Domingo, Domingo, he’s a takin’ me to Egypt.

I could sing until the crickets formed a chorus and chirped back at me and I’d never find Domingo.

He don’t show. I fancy he’s hiding somewhere, but fancying can’t get me far. And finally I do see a familiar face. I don’t need a wandering gypsy teller to read my fortune. Lavinia wasn’t hiding somewhere in the house when I exited without my dog. She ran to the Evergreens for Sue. And with her dark eyes and fierce features, Susie looks like she has been to Egypt, and now I’ll never get there.

“You can’t persuade me,” I hiss like a serpent. But my venom is small.

She smiles under her bonnet. “Will you make a spectacle of yourself right on the floorboards of your father’s depot?”

“It don’t matter,” I insist. “I’m the extravagant daughter who never dusts the stairs and who sails around with a big dog.”

“Emily, I will not leave this station until you march home with your portmanteau.”

“Why?” I ask, pretending to have Cleopatra’s swagger in matters of love and war. “Are you frightened of a little scandal? Ralph Emerson will boycott your salon and Mr. Sam Bowles will never leave his hat again on your settee.”

“Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, you are hurtful and imbecilic.”

“But those are useful ingredients in a war.”

She laughs the bitterest laugh I have ever heard. Her mouth is blue from all the bitterness. “War against whom, my dear?”

“The Evergreens and the Homestead.”

“Perhaps I have neglected you during the scarlet-fever outbreak. I did not have time to answer all your notes.”

“But you had the time to show Father pages of your novel.”

My venom seems to bite. The hardness and calculation are gone. And she lapses into her old habit of a shivering lower lip.

“There is no such novel, you silly creature. I am not one of the Brontë sisters and never will be. I have no Jane Eyres or Rochesters in my narrow constitution. I only talked to Squire Dickinson about the idea of starting a novel, and he had the graciousness to listen. Would you really run away with a ne’er-do-well, a gambler who robs people of their bread and butter?”

“I would.”

“And break your father’s heart?”

“He don’t have a heart to break.”

That lower lip stops trembling. Sister Sue might have commenced strangling me had she been in less public a place.

“The Squire loves you to distraction. He thinks of nothing but his family and its welfare.”

“Then why don’t he let me marry a man?”

“Good Lord, how many suitors have you and your sister spurned?”

“At least a hundred,” I lie. “And likely a hundred more. But it’s too late for Pa-pa to appear with his lantern. I’m leaving…with Brainard Rowe. I love him, Susie. And I want to trade in love, just like Cleopatra. I’ll never have another chance. Didn’t we both swear that we’d never abandon wonder? Well, Brainard is my own pale storm. And I ain’t giving him up.”

But Susie mocks my battle cry. “Sister, you could stand here forever and he still wouldn’t come.”

“Did you meet with my man?” I ask like the meekest squirrel.

“I certainly did. I found him skulking behind a barn near the depot. And I warned him that if he did not disappear and promise never to plague you again, I would make sure he was delivered to the penitentiary.”

“And I will wager with my life that he cursed every railroad detective in Massachusetts and laughed in your face.”

Suddenly I’m not so sure. Susan hands me an envelope with some scratchings on it in that oily butcher’s crayon she carries around in case she has a fit of inspiration. I peruse the envelope.

Daisy—Domingo!

I loved him for the terseness of that note. He didn’t palaver with an oily crayon, didn’t scribble ten thousand excuses. He wrote just enough to make certain I’d realize the note was authentic. I could sense the despair in that long dash between Daisy and Domingo, as if it were a frozen sea.

I shut my eyes and pretend I’m on the train with my man. His shoes still want polishing. I don’t care. I nestle my tawny scalp in his summer coat, right under the crooked strings of his cravat. I cannot hear the murmur of his heart. Our seats are made of a rough rattan that’s like a nest of thorns. It don’t bother me. I’m an heiress with five gold pieces in her pocket and another four inside her ruche. But it ain’t wealth that interests this heiress. It’s the light that pours through the mucked-up windows on Father’s train. It’s as slanted as a melody of mine. The light is laden with dust and tiny bugs that swirl like an army in retreat. And it’s peculiar, because all that busyness of bugs seems to lend the light a golden hue.

It’s the same shower of light that accompanied the Savior when He visited Amherst during one of the Awakenings. I was a child of six or seven. Every face was filled with the gravity of God. Sensible women fainted in the street. Men wandered into the fields and muttered to themselves like lunatics after seeing the Lord. But I was different. I squeezed my eyes, certain that the Savior would come. And the Savior did come, shrouded in that golden light. He stood near the gate of our Mansion on West Street, his beard as red as Pa-pa’s side-whiskers, while I wondered if the Lord was a Dickinson! I rushed into that shower of light, feeling the Lord’s glow on my eyelids.

I don’t have to rush right now. The Lord’s golden light was taking me and my man West. And I’ll worry when we get there!

Excerpted from THE SECRET LIFE OF EMILY DICKINSON © Copyright 2011 by Jerome Charyn. Reprinted with permission by W. W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved.

The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 348 pages

- Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

- ISBN-10: 0393339173

- ISBN-13: 9780393339178