Excerpt

Excerpt

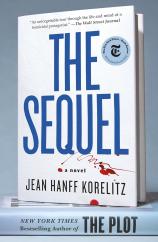

The Sequel

Chapter One

It Starts with Us

First of all, it wasn’t even that hard. The way they went on, all those writers, so incessantly, so dramatically, they might have been going down the mines on all fours with a plastic spoon clenched between their teeth to loosen the diamonds, or wading in raw sewage to find the leak in the septic line, or running into burning buildings with forty-five pounds of equipment on their backs. But this degree of whining over the mere act of sitting down at a desk, or even reclining on a sofa, and … typing?

Not so hard. Not hard at all, actually.

Of course, she’d had a ringside seat for the writing of her late husband’s final novel, composed—or at least completed—during the months of their all-too-brief marriage. She’d also had the master-class-for-one of his previous novel, the wildly successful Crib. True, the actual writing of that novel had predated their meeting, but she’d still come away from it with a highly nuanced understanding of how that extraordinary book had been made, its specific synthesis of fiction (his) and fact (her own). So that helped.

Another thing that helped? It was a truth universally acknowledged that finding an agent and then a publisher were hoops of fire that anyone else who wrote a novel had to face, but she, herself, was to be exempt from that particular ordeal. She, because of who she already was—the executor of her late husband’s estate, with sole control of his wildly valuable literary properties—would never need to supplicate herself at the altar of the Literary Market Place! She could simply step through those hoops, to effective, prestigious representation and the Rolls-Royce of publishing experiences, thanks to Matilda (her late husband’s agent) and Wendy (his editor), two women who happened to be at the apex of their respective professions. (She knew this not just from her own impressions but empirically; a certain disgruntled writer had taken revenge on the publishing monde by ranking every editor and agent from apex to nadir on his website—and making public their email addresses!—and even people who thought him otherwise demented admitted that his judgment, in these matters, was accurate). Having Matilda and Wendy was an incalculable advantage; the two women knew everything there was to know about books, not only how to make them better but how to make them sell, and she, personally, had zero interest in writing a novel if it wasn’t going to sell like that other novel, the one nominally written by her late husband, Jake Bonner. (Though with certain unacknowledged assistance.)

Initially, she’d had no more intention of writing a novel than she had, say, of starting a fashion line or a career as a DJ. She did read books, of course. She always had. But she read them in the same way she shopped for groceries, with the same practicalities and (until recently!) eye on the budget. For years she had read three or four books a week for her job producing the local radio show of a Seattle misogynist, dutifully making notes and pulling the most sensational quotes, preparing Randy, her boss, to sound like he’d done the bare minimum to prepare for his interviews: political memoirs, sports memoirs, celebrity memoirs, true crime, local-chef cookbooks, and yes, the rare novel, but only if there was some kind of a TV tie-in or a Seattle connection. Hers had been a constant enforced diet of reading, digesting, and selectively regurgitating the relentless buffet of books Randy had no intention of reading himself.

Jacob Finch Bonner had been the author of one of those rare novels, passing through Seattle with his gargantuan bestseller, the aptly named Crib, to appear at the city’s most prestigious literary series. She had lobbied hard to have him on the show, and she had prepared Randy as carefully as ever for their interview—not that it mattered, Randy being Randy—or perhaps even more carefully. She’d left the radio station and the West Coast a couple of months later, to ascend to the role of literary spouse and widow.

Matilda and Wendy weren’t just gatekeepers to the kind of success writers everywhere fantasized about; they were capable of actually transforming a person’s writing into a better version of itself, which was a real skill, she acknowledged, and something she personally respected. But it had nothing to do with her. She, herself, had never aspired to write so much as a Hallmark card. She, herself, had no intention of ever following Jake down that garden path of literary seduction, with its faint whispers of acclaim. She lacked, thank goodness, any wish for the kind of slavish worship people like her late husband had so obviously craved, and which he had managed, finally, to attract. Those were the people clutching his book as they approached Jake at the signing table after his events with a quaver in their voices, declaring: “You’re … my … favorite … novelist…” She couldn’t even think of a novelist she would travel across town to listen to. She couldn’t think of a novelist whose next work she was actively waiting for, or whose novel she even cared enough about to keep forever, or whose signature she wanted in her copy of their novel.

Well, possibly Marilynne Robinson’s in a copy of Housekeeping. But only as a private joke with herself.

Even deeply ungifted novelists had to have a vocation, she supposed. They had to believe they’d be good enough at writing to even try writing, didn’t they? Because it wasn’t the kind of thing you did on a whim, like making the recipe on the bag of chocolate chips or putting a streak of color in your hair. She was the first to say that she lacked that vocation. She might even admit that she had never had a vocation of any kind, since the only thing she had consistently longed for, since childhood, was to simply be left alone, and she was only now, on the cusp of forty (give or take) and cushioned by her late husband’s literary estate, within striking distance of doing just that. At last.

Frankly she’d never have done the thing at all if not for something she had said without thinking, in an interview for that very same literary series in Seattle, her adoptive hometown, when a pushy bitch named Candy asked, in front of a thousand or so people, what she was thinking of doing next.

Next as in: once you are finished with this public mourning of your husband.

Next as in: once you’ve returned to your own essential pursuit of happiness.

And she had heard herself say that she was thinking about writing a novel of her own.

Immediate approbation. Thunderous applause, with a chorus of You go, girl! and I love it! There was nothing wrong with that, and she didn’t hate it, so—not unreasonably—she’d made a habit of reprising the statement in subsequent interviews as she traveled around the country and abroad, representing her no longer available husband and in support of his final novel.

“What are your own plans?” said a professionally sympathetic book blogger at the Miami Book Fair.

“Have you given any thought to what you’ll do next?” said an editorial director at Amazon.

“I know it’s hard to see beyond the grief you’re going through right now,” said a frozen-faced woman on morning TV in Cleveland, “but I also know we’re all wondering what’s next for you.”

Actually, I’m thinking about writing a novel …

Everywhere she went it was the same powerful icebreaker: wet eyes, vivid smiles, universal support. How brave she was, to turn her heartbreak into art! To set her own path, unafraid, up that same Parnassus her late husband had scaled! Good for her!

Well, she had nothing against free and free-flowing goodwill. It was much easier to be admired than to be reviled, so why not? And also it helped that no one ever once referenced an earlier mention of this great revelation. I hear you’re writing a novel! How is that coming along? When can we expect to see it? Not even: What’s it about?

Just as well, because it wasn’t about anything, and it wasn’t coming along at all, and they shouldn’t expect to see it ever … because it didn’t exist. There was, as Gertrude Stein had once so famously said, no there there, and yet the mere notion of this mythical novel had carried her out of a grueling and drawn-out year of literary appearances on waves of applause. And not—it was worth noting—applause for Jake and his tragic mental health struggles or rumored persecution (probably at the hands of some jealous failed writer!), and not applause for his sad posthumous novel, either. Applause for her.

It was not in her nature to be troubled by an instance of such mild subterfuge, and she was not troubled by it, but she did wonder if there might be a horizon for all of this warm and fuzzy positivity. Was there some ticking clock out there, already set to expire when she mentioned her fictional(!) novel for the twentieth time, or the fiftieth, or the hundredth? Would some future interviewer, revisiting the tragic story of Jacob Finch Bonner and the success he barely got to enjoy after so much hard work, finally ask his widow whatever happened to the novel she herself was supposedly writing?

No one would, she suspected. Even if her vague ideation lingered in someone’s memory or newspaper profile, wouldn’t everyone just assume that the nonappearance of said aspirational fiction must mean that she, like so many others, had fallen short when it came to actually getting the thing onto the page? Yes, even she, the widow of such a talented writer, with all she must have learned from him, and with her very public fiction-inspiring personal tragedy—the spouse of a suicidal writer!—had simply failed to produce a good enough novel, or any novel at all. That was precisely what happened to so many people who tried to do so many things, wasn’t it? A person says they’re going to lose ten pounds or quit smoking or write that novel, and yet you spy them sneaking a cigarette out by the dumpster, or—if anything—bigger than they were before! And you simply think: Uh-huh. And that’s the end of it. No one ever actually confronts that person who fails to do that thing they were almost certainly never going to get done. No one actually ever says: So, what happened to that plan of yours?

Besides, who really needed her to write a novel? The world was jammed full of people supposedly writing their novels. Jake was assailed at every appearance by people who were writing them, or said they were writing them, or wanted to one day be writing them, or would be writing them if only they had the time or the childcare or the supportive parents or the spouse who believed in them or the room-of-one’s-own, or if some awful relative or ex-spouse or former colleague were dead already and no longer alive to disapprove of a book that would sorta kinda be based on them and might even sue its author! And those were just the people who weren’t even getting the words onto the pages; what about the ones who were? How many, at this very moment, were in fact actually writing their novels, and talking (annoyingly) about writing their novels, and complaining (even more annoyingly) about writing their novels? So many! But how many of those novels would actually get to the finish line? How many of the ones that did would be any good? How many of the ones that were any good would find agents, and how many of the ones with agents would get publishers? Then, how many of the ones that got published would ever even come to the attention of that precious slice of the human population who actually read novels? Sometimes, when she was in bookstores, tending to the business of being Jake’s widow and executor (and heir), she would stop in front of the New Fiction section and just gape at all of them, that week’s new publications enjoying their brief moment in the limelight. Each of them was a work that had been completed, revised, submitted, sold, edited, designed, produced as a finished book, and brought to the reading public. Some of them, she suspected, were better than others. A few might actually be good enough to have earned the grudging approval (perhaps even envy) of her late husband, who knew a well-written and well-crafted work of fiction when he encountered one. But which among these many were those few? She certainly didn’t have the time to find out. Or, to be frank, the inclination.

Anyway, in a week or two, all of those books would be gone—the not-good ones, the competent but undistinguished ones, even the few that might actually be exceptional—and the New Fiction section would be full of other new novels. Newer new novels. So who even cared?

It was the agent, Matilda, who waded into all of this uncertainty, referencing directly the supposedly-being-written novel (News to her! But she was delighted!) and suggesting she apply to one of the artists’ colonies—or not actually, technically apply, since Matilda had an author who was on the admissions committee and could prioritize the special circumstances of a celebrated literary widow attempting to write a novel of her own. She herself hadn’t heard about these colonies, not even from her late husband, and she did find that interesting. Had Jake never talked about them because he’d never been admitted to one, either as a young writer (not promising enough?) or later, as a blindingly successful one (too successful to deserve a residency, not when there were so many struggling writers out there!). She was surprised to learn that a dozen or more of these places were tucked into rural spots all over the country, from New England to—astonishingly—Whidbey Island, Washington, where she had spent a number of illicit weekends with her boss during her Seattle years. And apparently, according to Matilda at any rate, every one of these would be ecstatic to host her in support of the theoretical novel she was theoretically writing.

The colony to which she (or, more accurately, Matilda) had submitted her request for a residency was located in a New England town not so different from the one she’d grown up in, and comprised the home and expansive grounds of a nineteenth-century composer. She had a room in the main house, where the writers (and artists and composers) gathered for breakfast and dinner, and a little cabin down a path carpeted with pine needles, where she took herself each morning, like Little Red Riding Hood, except in this case the basket of food was delivered to her at lunchtime, set carefully on the back porch by a man who then drove away. The basket contained wax paper–wrapped sandwiches, an apple, and a cookie. Inside, the cabin was rustic and spare, with a book of testimonials from writers who’d worked there, a rocking chair, a fireplace, and a narrow cot on which she lay, staring at the cobwebs hanging from the rafters: empty, untroubled, mildly curious as to what she was supposed to be doing with herself.

The cardinal rule of the place was that no one should interrupt an artist at work (any one of them might be grappling with “Kubla Khan”!), so she was entirely alone for hours at a time. That was a powerful luxury. She’d been on the road for months by then, chatting away about Jake’s posthumous novel (and even more frequently: his tragic, premature death), and she was thoroughly sick of other people. All of that concern, all of the personal offerings of tantamount mourning (my mother, my father, my brother, my sister, my husband also!) which was somehow meant to bind these strangers to her. After the first day or two at the colony, when she understood that no one would bother her for glorious hours at a time, she relaxed.

She was, of course, not writing “Kubla Khan.” She was not writing anything, not for her first week in that little cabin, anyway. She spent the days moving from the cot to the rocking chair, lighting her fire (it was spring, but still very cold) and keeping it going, napping in the afternoons. She absolutely appreciated the stillness and warmth and the fact that her cell phone got terrible reception here. She spent a day reading a biography of the American composer whose home she was living in, and went for a few afternoon drives around southern New Hampshire. When evening came, she returned to the dining room in the main house and listened to the faux self-effacement of her fellow colonists, who preferred not to say outright how important they felt themselves to be. After dinner there was the occasional artist-talk about the sculpture or composition or performance art commission in progress elsewhere on the colony grounds. Two of the men—an aggressively atonal composer and a writer of metafiction—were having an obvious liaison, but this was abruptly ended by a surprise visit from one of their spouses, after which a toxic bitterness settled between them and emanated throughout the larger group. A silent elderly woman, apparently famous for her poetry, departed, and a ferocious young person replaced her, making each dinner a combative scene of barely suppressed hostility.

One night a novelist in residence gave an after-dinner reading in a separate building where the works of former colonists joined the surviving library of the estate’s original owners. She sat in an armchair while he read a pained description of a farmhouse creaking through an Iowa winter. It was deadly, and she was too bored to do anything but concentrate on her own facial expression, keeping it as near as she could to engaged interest. This person had a newly minted MFA and a newly signed contract with Knopf for his first novel, of which this inert prose comprised the opening chapter. When he finished, there were polite questions: How did a novelist incorporate visual impressions into written description? What was the influence of place on his work? How engaged should a writer be with the idea of gendered perspective?

She wasn’t paying much attention to this, either, so it was a rude interruption when the novelist tossed one of these questions in her own direction.

“What is it like for the rest of us writers? I don’t want to speak for you.”

He was looking at her.

What was what like?

“Oh,” she said, rousing herself. “I’m not sure I can answer. It’s very new for me, all of this. Writing, I mean.”

Now they were all looking at her. Every one of them.

“You mean,” said the combative young person, “you’ve never written before?”

“I haven’t published yet,” she amended, and hoped that would be that.

The person stared at her.

“How’d you get in here? I have friends who get turned down year after year. They have books.”

Nobody spoke.

“Well,” said someone, after a very uncomfortable moment, “it’s not just about publications. It’s talent.”

A performance artist with three long skinny plaits now elbowed the offended person and began speaking into that person’s ear.

“Oh, okay,” the no-longer-quite-so-offended person said. “I get that.”

Get what? Anna thought, but of course she knew. She knew that, to them, these real artists, she was no more and no less than the special case, the literary widow who was being indulged, by someone who ought to have known better. She was not to be admired for this, obviously. Neither was she to be pitied or given special consideration, let alone offered the undeserved leg up of an impossible-to-get residency at this temple to art, just because what she was attempting, in writing her nonexistent novel, was apparently very noble and redemptive! And also: so feminist!

Well, fine. She got that, but then again, why shouldn’t she be as fine a writer as her dead husband, who had left literature so prematurely, so long before his many theoretically great works could be written? So what if she, the widow, had shoved unnumbered “real” writers out of the way in her noble pursuit of fiction! Perhaps this particular enraged writer, or their deserving friends, had been passed over for a cabin in the woods and a picnic basket on the doorstep, but did any of them have any idea what she had had to endure, just to get here? Which of these poseurs was remotely qualified to pass judgment on her?

None of them, obviously. This Iowa auteur with his creaking house on the snowy prairie? The other auteur writing his navel-gazing “metafiction”? The new person, who was apparently writing a thousand-page dissection of a dying Rust Belt town, the subject of a recent bidding war?

She might not know much about fiction, but she knew she had no interest in reading any of those books.

There was applause. This literary event, mercifully, was over. Across the room, somebody opened a bottle and eased the plastic cups out of the plastic sleeve. The performance artist slipped out into the night, to return to her studio. One of the composers began flirting aggressively with a wan young poet from Brooklyn. Every one of the writers gave her a wide berth, either because she had embarrassed them or because they were embarrassed on her behalf. She didn’t know and she didn’t care. She considered them absurd people who prioritized absurd things, like whether a review had a box around it or a star next to it, or who’d been invited to some festival to read their pages to the empty seats in the tent, or whether they’d been deemed a twenty-under-twenty or a thirty-under-thirty, or, for all she knew, a ninety-under-ninety. What did it matter? More to the point, what difference did any of it make to how good the books they wrote actually were, or whether a normal person—herself, for example—would even want to read them?

Anna Williams-Bonner watched them, the writers, as they drifted across the library to the opened wine and the plastic cups and offered up laughably shallow praise to the man who’d just read to them. Then, before her eyes, the group defaulted to their eternal topics: the shortcomings of their former teachers, the inadequacies of the publishing world, and inevitably the writers they knew who happened not to be present tonight, in the library of this old New Hampshire mansion that art had built, long ago in a less complicated time. And she thought: If these idiots can do it, how fucking hard can it be?

Copyright © 2024 by Jean Hanff Korelitz

The Sequel

- Genres: Fiction, Psychological Suspense, Psychological Thriller, Suspense, Thriller

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Celadon Books

- ISBN-10: 1250408369

- ISBN-13: 9781250408365